Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Foreword

- MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR

- PREFACE

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Chronology

- PART ONE Merdeka or Medicine?

- Chapter One The Acting Prime Minister Dies

- Chapter Two Life before Politics

- Chapter Three UMNO and the Road to Merdeka

- Chapter Four Positioning Malaya in the World

- Chapter Five The Making and Partitioning of Malaysia

- PART TWO Remaking Malaysia

- List of Abbreviations

- Bibliography

- Index

- Photographs

Chapter Five - The Making and Partitioning of Malaysia

from PART ONE - Merdeka or Medicine?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 October 2015

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Foreword

- MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR

- PREFACE

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Chronology

- PART ONE Merdeka or Medicine?

- Chapter One The Acting Prime Minister Dies

- Chapter Two Life before Politics

- Chapter Three UMNO and the Road to Merdeka

- Chapter Four Positioning Malaya in the World

- Chapter Five The Making and Partitioning of Malaysia

- PART TWO Remaking Malaysia

- List of Abbreviations

- Bibliography

- Index

- Photographs

Summary

On 27 May 1961, Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman made the first public reference to the Federation of Malaysia at a Singapore press luncheon, setting off speculation and criticism throughout the region (Memo 23 February 1962). The idea was not new, but where British strategic considerations and local political developments were concerned, the time for it now seemed ripe. The incorporation of Singapore into Malaysia, along with Sabah, Sarawak and Brunei — the last of which eventually chose to stay out — offered the best chance to save the island from a communist takeover (Lam and Tan 1999, pp. 55–56).

The term “Malaysia” had in fact been in use before any talk of independence for such a polity had been advanced. For example, the classic study of the colony by Rupert Emerson from 1937 was titled “Malaysia”.* Incidentally, “Malaysia” was also the name preferred by UMNO when the matter was discussed within the Alliance before independence. In a memorandum to the Reid Commission written on 25 September 1956, the Tunku stated that it was the MCA that wanted the new country to be called “Malaya” (CO 889/6, ff 219-239 — Stockwell 1995, p. 307).

By 3 June 1961, Singapore's PAP had accepted the Tunku's merger proposals (TS–IAR14/1/2). That same week, however, Singapore UMNO, Singapore MCA and the defeated SPA formed an alliance reminiscent of Malaya's successful consociation. This greatly upset the PAP, which was in an unstable state despite its electoral victory. According to B. Simandjuntak, it was this turn of events that precipitated the emergence of the splinter party, the Barisan Sosialis Party (BSP). With Dr Lee Siew Choh as president and Lim Chin Siong as secretary-general, this new grouping came into being on 17 September 1961 (TS–IAR/14/1/3) to become the PAP's most effective opposition (Simandjuntak 1969, p. 117). Within hours, 35 of the 51 branch committees, 19 of the 23 organizing secretaries and “about 70 per cent of the PAP's rank and file” defected. The split cut through the party all the way down to stationery and furniture being ferried away from PAP offices. The ease with which its departing left-wing managed to floor the party left a deep and lasting impression on remaining members (Milne and Mauzy 1990, p. 57).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

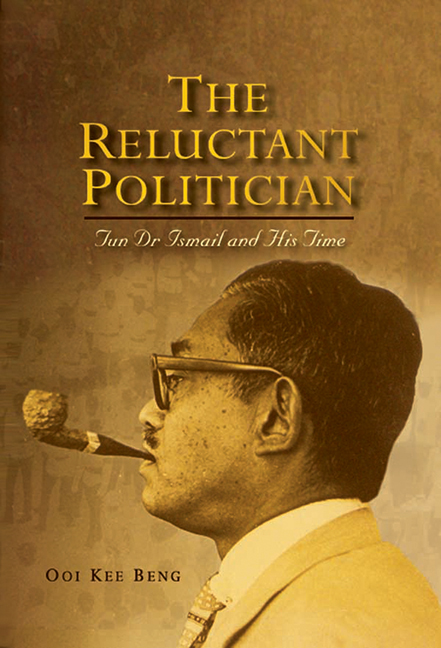

- The Reluctant PoliticianTun Dr Ismail and His Time, pp. 137 - 182Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2007