Abandoned mines are everywhere. Around the world, thousands of them are left behind where mining has ceased. Abandoned mines are not just spots made of holes in the ground. They can be open pits of immense proportions, with waste deposits on such a scale that new landforms emerge and with associated remains of derelict buildings and disused infrastructures. Mines affect entire regions. Communities have formed around them. Abandoning a mine often means emptying a village or a town.

Leaving extraction is a process worthy of study in its own right. Still, we know comparatively little about it. We know that mining is a huge planetary activity, and every new mine is prepared for years with prospecting, planning, anticipation, investment, and building, followed by the period of production. We also know that mining in the Anthropocene is a massive, geo-anthropological and geo-social undertaking, a formidable network of mines and supply chains and financial institutions, indeed a “planetary mine” (Arboleda, Reference Arboleda2020; Sörlin, Reference Sörlin and Sörlin2023, see Chapter 1). Extractive industries massively affect geopolitics and global sustainability. They are a super emitter and – polluter. Abandoning mines is, consequently, an equally vast enterprise, albeit much less known. If the goal is sustainability, the process of re-purposing and re-orienting mining geographies should be a priority for further reflection and research. The Arctic is no exception.

Much of the impact that mines have is environmental, which is the focus of this chapter. Over the last hundred years, mining has left increasingly large-scale wounds in the landscape, with polluted soil, water, and air, and affected plant and animal life. The mining industry is one of the largest producers of industrial waste in the world. In Sweden, the sector produced between 77 percent and 82 percent of all industrial waste in the country in the period 2010–2016 (Naturvårdsverket, 2018). Large socio-technical systems for mining, not least infrastructures for transport and energy, may affect other land users negatively (Avango, Reference Avango2020). Environmental impacts of mining have been at the center of a critical debate about metal demand in society and the interests of the mining industry, pitted against the goal of protecting natural environments (e.g., Müller, Reference Müller2014). To reverse the amount of degraded land, ecosystem restoration has been acknowledged as an important and necessary activity over the last decade (Benayas et al., Reference Benayas, Newton, Diaz and Bullock2009; CBD, 2010; Comín, Reference Comín and Comín2010; Bullock et al., Reference Bullock, Aronson, Newton, Pywell and Rey Benayas2011; Aasetre, Hagen, & Bye, Reference Aasetre, Hagen and Bye2021). In general rewilding, large-scale ecosystems are restored (Houlston & Shepherd, Reference Houlston and Shepherd2016), returning a landscape to the condition it was in before humans modified it. However, rewilding projects have different goals, tools, and methods depending on starting points and angles of approach (Jørgensen, Reference Jørgensen2015; Aasetre et al., Reference Aasetre, Hagen and Bye2021). This is underlined by a large and diverse body of literature dealing with adaptive reuse of brownfield sites, including political and economic issues (Hula, Reese, & Jackson-Elmoore, Reference Hula, Reese and Jackson-Elmoore2016), contamination (e.g., Hollander, Kirkwood, & Gold, Reference Hollander, Kirkwood and Gold2010), social aspects (Kühne, Reference Kühne and Kühne2019), legal issues (e.g., Guariglia, Ford, & Darosa, Reference Guariglia, Ford and Darosa2002; Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Franz, Edwards, Phalen and Nathanail2007), and questions of historic preservation (e.g., Baker, Moncaster, & Al-Tabbaa, Reference Avango, Lépy, Brännström, Heikkinen, Komu, Pashkevich, Österlin and Sörlin2017).

Research in the hard sciences is of utmost importance for tackling environmental impacts from the extractive industries that are rapidly expanding the “planetary mine.” In this chapter, however, we will argue that the scope of environmental remediation research should be widened beyond the confines of the engineering- and natural sciences, to encompass the humanities and social sciences. The aim of the chapter is to show that environmental remediation is not only a matter of finding effective technologies for dealing with toxic waste. The success or failure of environmental remediation of former mines can be just as much a societal issue as a technological one. The European Arctic serves in fact as an excellent lens for exploring societal dimensions of environmental remediation processes, because of relatively dense population and the wide range of societal actors and interests in the region, and the severity of the impacts.

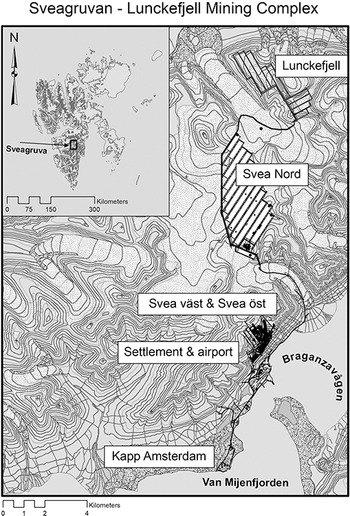

We will home in on the social and environmental history of two restoration projects – the former mines in Nautanen in Norrbotten, Sweden, and the Lunckefjell and Sveagruva mines on Svalbard. Environmental remediation on these sites has taken shape in very different contexts. At Lunckefjell it was initiated in accordance with the environmental law for Svalbard, with a mining concession that required the complete removal of all traces of the mining past. When the mine closed in 2016 the owner – the Norwegian government – not only remediated Lunckefjell but it also decided to eradicate all remnants of a much larger mining system of which Lunckefjell was part – the Sveagruva mine. The clean-up- and transformation project was launched as one of the most ambitious environmental projects ever to happen in Norway, already selling itself as a global environmental leader (Anker, Reference Anker2020). The industrial landscape was to be restored into a natural landscape, leaving only a few traces from the former industrial activity, legally protected as cultural heritage (Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Erikstad, Flyen, Hanssen, Moe, Lie Olsen and Veiberg2018) and incorporated into an existing National Park surrounding the site. What were the Norwegian motives? To protect the environment but also to safeguard Norwegian sovereignty at Svalbard.

The second mine, at Nautanen, was closed in 1908 after having been in operation for only a few years. At the time of closure there were no laws requiring environmental remediation of former mining sites. Nautanen was simply abandoned, although not forgotten. Unknown to most people, the remains of the mine continuously polluted the environment through the release of heavy metals into the water system. This became clear only in 1993 and triggered a number of investigations and environmental remediation efforts extending over more than two decades. Both state and corporate actors were involved. After millions in state investments and large-scale removal of waste rocks from the area, the environmental remediation of Nautanen came to a halt in 2017. The residues from mining and smelting remained, however, and still pollute the environment today.

Why did these two environmental remediation projects turn out so differently? Why has it been possible to remove every trace of former mining at the extremely remote Lunckefjell-Sveagruva location in the high Arctic (Figures 9.1 and 9.2), while it has proven impossible to do the same at the much more accessible site in Nautanen? Our answer to those questions will rest on the archives of actors who were involved, as well as from interviews and industrial-archaeological fieldwork. We need to know: Who held a stake in the future of the former mines at Lunckefjell-Sveagruvan and Nautanen? What were their interests? How did they realize them and what was the outcome? By answering these questions, we will show that environmental remediation is a game set to satisfy the interests of actors competing over the future of the region. The stories we tell are also about the wider question: Who can determine the post-extraction future of Arctic mines and why?

Figure 9.2 The Lunckefjell mine with its access road in August 2016. The mine and the road have since then been removed, as part of the environmental remediation.

Previous Research on Environmental Remediation

Despite a huge body of literature from different disciplines dealing with adaptive reuse of brownfield sites, a focus on potential, emerging, and ongoing mining industries is the general tendency in existing academic literature. The closure of mines and their transformation and afterlives has been less described and discussed (Hojem, Reference Hojem2014). Mining in the European Arctic has been going on since at least the seventeenth century, and the majority of the mining sites from this history have already been abandoned, some with significant amounts of toxic waste deposited in the environment (Avango & Rosqvist, Reference Avango, Rosqvist and Nord2021). Most of these sites do not create new detectable industrial values. Environmental historians Arn Keeling and John Sandlos have named them “zombie mines” – dead, but continuing to affect the environment with their toxic legacy (Keeling & Sandlos, Reference Keeling, Sandlos, Martin and Bocking2017).

Techniques for remediation of mine waste span a wide range depending on, for example, the type of polluting substance and environmental setting. For instance, acid mine drainage is formed from sulfidic mine waste exposed to air and water and is usually spread through hydrological pathways. Combustion fumes from processing the ore can also contain high levels of sulfur dioxide that later falls as atmospheric deposition and acidifies soils and freshwater systems. Depending on proximity to settlements or sensitive environments (a drinking water supply resource, nature reserve etc.) and economic capacity, the remediation strategy might differ substantially. Research on remediation strategies has included costly and monitoring-heavy active treatment (e.g., liming the water, adding chemicals) but also passive and semi-passive treatment (e.g., utilizing natural microorganisms in wetlands or bioreactors) with the goal to reduce the mobility of metals and keep them from spreading to the surrounding environment (Gong, Zhao, & Wang, Reference Gong, Zhao and Wang2018). Mine waste remediation in colder climates has to consider lower temperatures (i.e., substance degradation is low) and a strong seasonal variability in spreading pathways. Most passive (and more sustainable) remediation techniques for colder climates are still only at the laboratory scale, although some studies show successful metal retention even at temperatures down to 3°C (e.g., Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Janin, Coudert, Blais and Mercier2018).

Within landscape- and natural science, restoration and rewilding involves contributing to the restoration of an area that has been destroyed or disturbed, so that nature values and ecosystems can be preserved (Lammerant et al., Reference Lammerant, Peters, Snethlage, Delbaere, Dickie and Whiteley2013). In the past, restoration projects tried to recreate “original” nature. Recent projects instead respond to the fact that nature is dynamic, and that climate and other conditions affect the landscape. Today’s focus in restoration projects is therefore restoring or facilitating ecological processes and functions enabling ecosystem services and habitats for species to remain resilient in the long term (Hagen et al., Reference Hagen, Erikstad, Flyen, Hanssen, Moe, Lie Olsen and Veiberg2018). According to Díaz et al. (Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo, Agard, Arneth, Balvanera, Brauman, Butchart, Chan, Garibaldi, Ichii, Liu, Subramanian, Midgley, Miloslavich, Molnár, Obura, Pfaff and Zayas2019) the largest global threats to biodiversity and ecosystems are caused by anthropogenic degradation of landscapes. Presently, a substantial amount of scientific literature on restoring landscapes and nature exists (e.g., Dilly et al., Reference Dilly, Nii-Annang, Schrautzer, Schwartze, Breuer, Pfeiffer, Gerwin, Schaaf, Freese, Veste, Hüttl, Müller, Baessler, Schubert and Klotz2010; Borišev et al., Reference Borišev, Pajević, Nikolić, Pilipović, Arsenov, Župunski, Prasad and de Campos Favas2018; Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Settele, Brondízio, Ngo, Agard, Arneth, Balvanera, Brauman, Butchart, Chan, Garibaldi, Ichii, Liu, Subramanian, Midgley, Miloslavich, Molnár, Obura, Pfaff and Zayas2019; Evju et al., Reference Evju, Hagen, Kyrkjeeide and Köhler2020; Hancock et al., Reference Hancock, Martín Duque and Willgoose2020). Also, the European Commission is currently working on a new legally binding restoration law as part of the Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 and the European Green Deal (SER Europe, 2021). Golub, Mahoney, and Harlow (Reference Golub, Mahoney and Harlow2013) maintain that the emerging science of sustainability emphasizes interdisciplinary understandings and solutions of complex problems that are challenging human-ecological systems. According to Lorimer et al. (Reference Lorimer, Sandom, Jepson, Doughty, Barua and Kirby2015), rewilding projects also raise a series of political, social, and ethical concerns, conflicting with more established forms of environmental management, and requiring a rich conversation across the various disciplines of both the natural and social sciences. Restoration of industrial landscapes respecting pollution, natural, and cultural heritage aspects is nevertheless sparsely reported.

Sveagruva-Lunckefjell, Svalbard

Our first case, Sveagruva, has a long history characterized by two drivers of change – on the one hand fluctuations in the world market, and on the other changing geopolitical priorities, both triggering closures and reopenings. A British company were first to claim the area for coal mining in 1906, but it was Swedish companies, financed by the Swedish iron and steel industry, that from 1910 developed coal mining there – AB Isfjorden-Belsund. The steel industry had economic interests in Spitsbergen coal, but the company was also acting on behalf of the Swedish government to strengthen Sweden’s influence on the legal status of Spitsbergen, which Sweden, Russia, Norway, the United States, and other states were negotiating at the time. During the First World War, when prices of coal ran high, Swedish investors formed a new company – AB Spetsbergens Svenska Kolfält – which constructed and started the mine and the mining town Sveagruvan in the summer of 1917. In 1921, a severe international economic recession led to sharp price drops for coal. Consequently, the owners restructured the mining company, while the Swedish state financed investments in more effective production systems. These efforts eventually failed when the mine caught fire in 1925. The company decided to stop mining operations, and nine years later sold it to the Norwegian company Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani A/S (SNSK), in which the Norwegian State was the largest owner. SNSK wanted to buy it for geopolitical reasons – to ensure that the Swedish company would not sell it to the Soviet Union (Avango, Reference Avango2005).

SNSK did not open any mining operations at the site until after the Second World War, however. Starting in 1946, the company constructed an entirely new mining town – now named Sveagruva – since the German military had leveled the old Swedish mining settlement in 1944. SNSK did not mine for long, however, closing it down again after only five years. The company started operations again in 1970, with the intent to eventually scale up production at the site. In 1987, however, after a decline in world market coal prices, they closed Sveagruva again (Avango & Brugmans, Reference Avango and Brugmans2018).

In the late 1990s, after the Norwegian state had made it possible for SNSK to produce at a much larger scale than before, SNSK again developed plans to re-open Sveagruva. In 2001, the company opened a new coal mine they named Svea nord – the largest coal deposit operated on Svalbard to date. To enable it, the company greatly expanded the infrastructure by building a road across a glacier and a conveyor belt tunnel through an entire mountain. The company also increased the capacity of the Sveagruva settlement. The re-opening coincided with rising world market prices for coal, and when SNSK reached full production capacity at Svea nord, the company was able to make real economic profits for the first time in its history.

Building on this success, in 2013, SNSK opened yet another mine – Lunckefjell – which they connected to Sveagruva by new tunnels and a second glacier road through high alpine environments. By this time, however, world market prices for coal started to drop at a rapid pace, and in April 2016, SNSK placed mining operations on hold to avoid further economic loss. When coal prices eventually started to rise again, SNSK applied for permission to re-start the mine. By this time, however, political forces put a stop to further mining. In 2017, the Norwegian Storting decided to shut down all mining activity in Svea, and the mines were permanently closed in 2018 (Avango & Brugmans, Reference Avango and Brugmans2018). With this a 100-year mining history ended (Figure 9.3).

With the closure of the Svea mine, Store Norske was obliged to remove all traces of modern mining operations. This was anchored in the start-up permission of the Lunckefjell mines and in the Svalbard Environmental Act. An enormous clean-up and transformation project was launched, aiming to be fulfilled in 2023. After the Norwegian government placed the Lunckefjell coal mine on hold, a two-year period followed during which the future of the Lunckefjell-Sveagruva mine was up for discussion. Different actors envisioned different futures for the former mining area. Many people, typically current and former employees of SNSK, hoped that the government would decide to re-start mining at Lunckefjell and thereby save the massive investment the mining company had made in preparing it for extraction. Others ascribed additional values to the area – values that could be realized with or without re-starting the Lunckefjell mine. Actors within SNSK saw possibilities to re-use the mining settlement and infrastructure for industrial-related research, for example, developing cold climate technology for shipping and mining, and for practicing environmental cleanup operations such as oil spills on ice.

By offering the Sveagruva-Lunckefjell system to companies interested in conducting such research, SNSK would be able to generate new income. The idea of making Sveagruva-Lunckefjell into a research site was also shared by actors at the University center of Svalbard and Norsk Polarinstitutt, but they held other visions about the purpose of the research. They envisioned that Sveagruva could become a hub for geological research in an area of Svalbard that geologists tend to visit more seldom because of the distance from the university, which is located in Longyearbyen. In addition to research, Sveagruva could be used to house students and labs during field-based courses in various disciplines at the University Centre in Svalbard (Anonymous, interview by Avango in Longyearbyen, August, 2016). There was also considerable interest in Sveagruva among tourism companies active on Svalbard. Tour operators based in Longyearbyen saw the mining settlement as a potential hub for snowmobile-based groups, which could use the housing available there to stay for a couple of days, making excursions into spectacular surrounding landscapes that are difficult to access from Longyearbyen. There were also entrepreneurs who saw the possibility of opening a guest house with a restaurant at Sveagruva on a seasonal basis. All tourism companies also saw potential in the material remains from the history of Sveagruva, which they could use as anchor points for narrating the dramatic history of the mine to tourists (Anonymous, interview by Avango in Longyearbyen, August, 2016).

The Governor of Svalbard’s department for environmental protection, tasked with cultural heritage protection of the islands, shared the tourism entrepreneurs’ evaluation of the remains from mining, but from a legal perspective. According to environmental law on Svalbard, all remains from human activity that pre-date 1946 are automatically defined as cultural heritage and protected as such for posterity (Marstrander, Reference Marstrander and Wråkberg1999). None of these ideas for repurposing were new on Svalbard, where several former mining towns and prospecting camps had been successfully repurposed for tourism, research, and education. Despite this fact, the Norwegian government decided in 2018 to remove all traces of the Lunckefjell-Sveagruva mining system. This included remains of all mines, the entire settlement with housing and service buildings, technical service facilities, an airport, roads and conveyor belts, washing and dressing plants, and an entire export harbor facility at Kap Amsterdam. Sveagruvan-Lunckefjell was to be literally wiped out, with the exception of a few remains from the Swedish mining period and the early Norwegian period prior to 1946, which are legally protected as cultural heritage.

The Environmental Remediation of Sveagruva-Lunckefjell

The overall goal of Norway’s Svalbard policy has been to maintain sovereignty. This has required Norwegian presence on the archipelago. No other industry has delivered as much Norwegian presence on Svalbard as mining over the last 100 years (Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2016). Pedersen (Reference Pedersen2017) argues that the closure of the mines at Svalbard will mean fewer Norwegian inhabitants and ultimately lead to misperceptions about the legal status of Svalbard. Further, this may pose new foreign and security policy challenges to Norway.

The Norwegian Parliament decision to terminate the mining activity in Svea and Lunckefjell (Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, 2017) must be understood against this background but also in the context of the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2001). The act states, in §64, that when industry or other activity at Svalbard ends, the owner is responsible for removing remaining installations and infrastructure and restoring the area to its original appearance. The Ministry of Justice further specified that infrastructure and buildings should be removed. With this decision, the range of different visions on how to reuse the Sveagruva-Lunckefjell system became impossible to consider. They all ultimately depended on a functional settlement with infrastructure and buildings, which would instead be removed.

On behalf of the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, Store Norske launched a thorough process planning the transformation of Svea. Their point of departure was clear. Unlike other closed mining sites at Svalbard, Sveagruva should be transformed into a place that as much as possible resembles the original state of the landscape, with the remains older than 1946 being the only exception. Environmental toxins were assumed to be the overarching problem in the transformation process. However, transforming the industrial landscape into nature and upholding heritage values in the remaining historic structures proved to be far more complex and intricate processes. The time schedule given by the Ministry was tight, and the planning process concerning the physical transformation started long before all decisions relating to the process were taken.

The remediation work started with the Lunckefjell mine in 2018 and has proceeded at a rapid pace since then, with the successive removal of the rest of the mines, the airport, the power plant, the deep-water quay, the mining settlement with over sixty buildings, huge industrial structures, and many kilometers of road (Figure 9.4). Tons of pulp will be removed and rearranged, while toxic spills will be removed or encapsulated. The reason why the Sveagruva-Lunckefjell mining area became subject to such a radical environmental remediation, despite the unprecedented high costs, was the need to fulfill the requirements of the Svalbard Environmental Act. There are, however, reasons to also consider other driving forces behind this huge and costly project – the geopolitics of mining at Svalbard.

The Norwegian government and SNSK have a history of proactively supporting Norwegian state influence that extends back to the formation of the company in 1916 and its active involvement in securing Norwegian sovereignty over Svalbard through the Treaty concerning Spitsbergen in 1920 (Mathisen, Reference Mathisen1954; Østreng, Reference Østreng1971). Until the mid-1920s, the Norwegian government supported even highly unprofitable mining operations at Svalbard (Johannessen, Reference Johannessen1996). After the Soviet Union had established several mining towns on Svalbard in the late 1920s and early 1930s, SNSK and the Norwegian state bought up mining properties from foreign companies that had seized their operations. The purpose was to ensure that Norway and Norwegian actors would control most of the lands on the archipelago and avoid increased Soviet presence on the islands (Avango & Roberts, Reference Avango, Roberts, Körber, MacKenzie and Westerståhl Stenport2017).

Sveagruva was a part of this geopolitics of mining right from the beginning, when SNSK bought the mine from Swedes to make sure that the newly formed Soviet company Trust Arktikugol would not be able to acquire it (Avango, Reference Avango2005). Since the 1930s, the mines in Svea have hardly been economically sustainable, except during the recent global mining boom after the millennium. Supporting Longyearbyen, with more than 400 jobs at its peak, Svea was the most important tool for maintaining Norwegian settlement – and sovereignty. To close the mine obviously posed some security policy challenges (Pedersen, Reference Pedersen2016). In 2016, the state bought the 218 square meters privately owned former coal mine of Hiorthhamn for 300 million Norwegian krone (35 million US Dollar) to avoid the risk that state-supported foreign actors, including China, would acquire it. Against this background, it is not far-fetched to consider the possibility that the removal of infrastructure and buildings would dramatically increase the cost for a company from China or Russia to restart mining at Sveagruva-Lunckefjell. Moreover, the Norwegian authorities plan to include the Sveagruva-Lunckefjell area in the Nordenskjöld land national park after the environmental remediation is finalized, which would make it very difficult to gain a concession for mining there.

Nautanen, Norrbotten

The Nautanen copper mine was established in 1902. The company, Nautanens Kopparfält AB, established it in order to profit from an increasing demand for copper, driven by industrialization in general and electrification, in particular. Another context working in favor of the mine was the expanding large-scale sociotechnical system for mining in the Swedish Arctic, built for mining iron ore at Malmberget and Kiruna. The company connected its copper mines and settlement to this system through an aerial ropeway, connecting the mine with the railway system at Koskuskulle (Avango & Rosqvist, Reference Avango, Rosqvist and Nord2021).

Nautanen became short-lived. In 1908, the company shut it down. During its six years of operation, the company had mined 72,000 tons of ore, or 2,000 tons of copper. After closing their mines and clearing the settlement of its more than 400 inhabitants, the bankrupt company sold off the buildings and infrastructures (Ollikainen, Reference Ollikainen2002). With the exception of one building, the only visible traces of Nautanen were the remains of house foundations, roads, mines, waste rock piles, tailings, and metallurgical slags. The latter contained sulfidic materials and were spread out across the landscape around the former processing plants and mines, on the ground and in lakes (Figure 9.5).

Over much of the twentieth century, Nautanen was an abandoned mining site. In the decades following closure, former workers and their labor organizations organized excursions to the site, using it for political mobilization against the capitalist system and for social reforms. From the 1970s, the site was reinterpreted as a cultural heritage site, in the beginning an unofficial cultural heritage defined by actors in the labor movement, and from the 1990s an official cultural heritage with a basic level of protection under Swedish heritage institutions.

From 1993, Nautanen became an object for concern regarding the state of the local environment at the site. In that year the County Administrative Board of Norrbotten, Sweden’s northernmost county, issued an inventory of abandoned mine waste. The inventory, performed with Luleå Technical University, found Nautanen, the second largest historical sulfide mine in Norrbotten, to have high copper concentrations in its discharging surface water (Larborn, Reference Larborn1993). A year later, further investigations detailed the findings (Länsstyrelsen i Norrbotten, 2002). The issue of toxic waste at Nautanen remained dormant for years. In 1999, the Swedish government implemented a new Environmental Code (Ebbesson, Reference Ebbesson2015: 52) and set aside funds for environmental remediation of polluted areas. From the early 2000s, the funding was put to use in Nautanen. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency granted the funding to the County Administrative Board as part of its regional program for polluted areas (Doc. 1). The challenge for the environmental remediation effort was not only about determining the extent of the contamination but also the responsibility for carrying out the remediation. The County Administrative Board examined this issue in 2002, concluding that no active party could be held responsible for the pollution, since mining company Nautanen Kopparfält AB had ceased to exist (Bothniakonsult, 2002).

With funding from the environmental protection agency, Gällivare Municipality launched a comprehensive investigation at Nautanen, including waste characterization, surface and groundwater samples, lake sediment records, and biological investigations. The final report was completed in 2002 with a risk assessment concluding that Nautanen reached the second highest risk class (MIFO risk class 2) of contaminated sites in Sweden, posing a substantial threat to aquatic ecosystems. The metal leakage mostly originated from concentration plant sands and waste rock piles that were in contact with surface water (Figure 9.6). The report recommended remediation by assembling and covering waste, and installing technology picking up toxic substances downstream from Nautanen (Botniakonsult, 2002).

Another suggestion was to re-process some of the waste rock with the highest ore grade at the mining company Boliden’s nearby copper mine Aitik and overrule the protection they had as cultural heritage. In 2005 and 2008, the company transported the waste rock by trucks and fed it into their concentration plant at Aitik, extracting copper, gold, and zinc (Botniakonsult, 2002). This project was not purely motivated by environmental considerations. Boliden had the resources and the economic incentive to do it. In 2009, the consultancy Hifab conducted an environmental impact assessment on behalf of Gällivare municipality, planning for removal of the contaminants remaining after Boliden’s removal of waste rock. The main plan was to redirect water streams running through the former concentration plant and smelter area, where tailings leached out metals (Hifab, 2009). Gällivare Municipality also launched an investigation examining whether Boliden’s removal of waste rock had any effect on water quality, which found little or no effect from this effort (Golder Associates AB, 2015).

Simultaneously with the planning for a continuation of the environmental remediation, a new challenge for the project appeared – a conflict with the landowner. The forest company Sveaskog had entered a formal agreement with the municipality back in 2006 to take on some of the remediation work, provided that the state would fund it. When the funding eventually came through, the agreement had already ceased. Now, Sveaskog no longer agreed to take responsibility for maintaining and monitoring the re-directed water streams at the site. They wanted to strictly limit their commitment to managing environmental data collecting devices and keep entrances to water tunnels free. For this reason, Gällivare municipality decided in 2014 to cancel the entire environmental remediation project at Nautanen, citing the excessive costs, and the fact that Gällivare municipality did not own the land – Sveaskog did (Doc. 2; Golder Associates AB, 2015).

In 2017, researchers from REXSAC conducted field research at Nautanen. Hydrological sampling in the area (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Rosqvist, Chalov and Jarsjö2020) revealed that the surface water system remains highly polluted. Synthesizing the available water quality measurements at Nautanen during the previous twenty-five-year period shows that Nautanen has reached a “steady-state” in terms of metal leakage: it will likely not decrease or increase in the future but has enough waste to keep polluting the area for centuries to come.

Extracted Places with Contested Futures

Different institutional framings explain the ways the two remediation projects developed. In Sveagruva-Lunckefjell, the mining company SNSK acted in accordance with the environmental law of Svalbard, which requires companies to restore the environment to its pre-mining state. In Sweden there are similar legal requirements, but those were not in place when AB Nautanens kopparfält closed their mine in the early 1900s. Although the responsibility for remediating mining sites can be transferred to new landowners under current Swedish environmental law, the present landowner, Sveaskog, managed to avoid that by buying the forest land one day before this environmental law came into effect. Therefore, the lack of legal tools is an important part of the explanation as to why the remediation of Nautanen has failed so far, while the remediation of Sveagruva has not.

A second important difference is ownership. SNSK is still an active mining company, with a physical presence in Svalbard and a wide portfolio of economic activities in Svalbard, while AB Nautanens Kopparfält has been gone since 1908. In the Nautanen case, there is no company around to cover the costs and the hard work of remediation. The history of Arctic mining is full of similar examples, for example, the Giant mine in the Northwest Territories in Canada, where gold mining between 1948 and 2004 generated employment and wealth but also a toxic legacy consisting of more than 200,000 tons of arsenic. The mining company has seized to exist, leaving Canadian taxpayers to cover the costs of remediating the mining site (Sandlos & Keeling, Reference Sandlos and Keeling2016). There are similar examples from the recent history of mining in the Swedish north (Müller, Reference Müller2014).

A third difference that also put the spotlight on the societal dimension of environmental remediation are the importance of interests of the actors involved for the outcome of the remediation process. In Svalbard, environmental remediation happened because a powerful actor – the Norwegian state – wanted it to happen. The state, owner of SNSK, acted in accordance with the law but also had geopolitical interests that are likely to have played a contributing role to the decision to order the complete eradication of the largest system for mining on the entire archipelago, for a price that by far exceeds any of the original estimations of the costs for remediation. It is most probable that an ambition to hinder agents of foreign powers from acquiring new land for mining in Svalbard, contributed to the willingness of the Norwegian government to act in this way, no matter the costs. In the future, when all that remains of Sveagruva-Lunckefjell are house foundations and shabby barracks protected as cultural heritage, the investment costs for starting a new mine are likely so high that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to acquire economic returns that would justify investment – at least for a company that needs to make a profit. Moreover, a company wanting to re-open mining at Sveagruva-Lunckefjell in the future would need to acquire a permit for mining in a national park. The chances that the Norwegian authorities would approve such an application seem slim.

The Norwegian policy on this matter can be interpreted in the context of Norwegian Svalbard policy over the last decade. Grydehøj et al. (Reference Grydehøj, Grydehøj and Ackrén2012) has pointed out that Norway’s top-down governance of Svalbard through the Governor of Svalbard and by supporting unprofitable mining companies for the sake of maintaining active populated settlement has been complicated in recent years. Growing economic diversity in the wake of mine closures and a growing tourism sector has brought multinationalism and local democracy to the archipelago. At the same time a new competing power on Svalbard and in the Arctic at large has emerged beside Russia – China. The Norwegian policy on the Sveagruva-Lunckefjell environmental remediation can be interpreted as a response to this new situation. Norway’s policy on climate change also contributes – large scale coal mining in a sensitive environment in the Arctic is an increasingly hard sell to voters in Norway.

In the case of Nautanen, it was the conflicting interests between the actors involved that stopped environmental remediation from happening – despite the relatively low costs involved (compared to the Svalbard case). On one side was the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, the County administrative board of Norrbotten, and the Gällivare municipality, who all wanted the remediation project to happen. Their interest, and ultimately the Swedish government’s, was to serve public interest and to meet policy goals for environmental protection and restoration of contaminated environments. The mining company Boliden also took responsibility for restoring the environment. Their interest was to create goodwill in a municipality where their company has large-scale mining operations running. Boliden’s interest was probably also to make a profit from re-mining the waste. The company had no legal responsibility to restore the environment as a whole, and therefore took out only what they wanted and left the rest for others to take care of.

What stopped the environmental remediation project from materializing was the fact that the landowner – the state-owned forest company Sveaskog – expressed no interest in contributing to stopping the leakage of substantial amounts of heavy metals and other toxic substances from their lands into the ecosystems in their forests. The forest company had found a way to avoid taking responsibility for toxic waste on their lands and utilized it, leaving the costs for environmental remediation of their lands to an economically weak municipality with no ownership responsibility for the land at all.

Conclusions

The cases indicate that it may be difficult to predict what post-extraction histories we can expect in current and future Arctic mines, which calls for caution when planning and giving permission to extractive mega-projects. Even if it is possible to mitigate and even undo environmental damage from a technological point of view, it may be hindered by unfavorable societal contexts and actors with competing interests.

Closed mines are a challenge, not only from an environmental point of view but also from a social one. When mines are closed, settlements, towns, and regions that depended on them are in need of new income opportunities, as well as opportunities enabling the preservation of societal services and quality of life that can disappear with the mine. Social challenges post-extraction can be particularly severe in sparsely populated areas. Nautanen and Laver (Avango et al., Reference Baker, Moncaster and Al-Tabbaa2023, see Chapter 10) are instructive examples. As we show elsewhere in this volume (Avango et al., Reference Baker, Moncaster and Al-Tabbaa2023, see Chapter 10; Malmgren et al., Reference Malmgren, Avango, Persson, Nilsson, Rodon and Sörlin2023, see Chapter 11), de-industrialized mining settlements can gain new values that sustain them beyond the end of extraction, through new economic activities, heritage making, or by reopening mining. At Sveagruva, actors in the mining industry, tourism, and science envisioned such futures but were unable to realize them. The same is true in Nautanen, where local actors in Gällivare as well as official Swedish heritage protection wanted to protect remains of mining as heritage. Unfavorable institutions, the interests of powerful actors, and global economic and political trends stood in their way.

A challenge to take on for research and development on environmental remediation in the future is to find ways to harmonize needs for remediation with possibilities to create new values. In recent years, companies in the mining sector and associated research environments have worked on this issue. How can processes for mine decommissioning and rehabilitation be designed in a way that allows for the creation of new values? How can the ambitions and voices of local communities in the vicinity of the former mines be taken into account when the future of their local environments is to be determined? To consider value creation in the decommissioning process of mines, in close dialogue with affected communities, may provide tools to harmonize sustainability goals that may otherwise be in conflict.

Introduction: Making Heritage and History

The increasing interest in mineral resources in Arctic Fennoscandia has been triggered by rising global demand and based on the prior existence of large socio-technical systems for extraction, energy, and transport. In public debates, there has been talk of a “mining boom” (Dale, Bay-Larsen, & Skorstad, Reference Dale, Bay-Larsen and Skorstad2018). Public statistics show the growth in numbers of exploration licenses and applications for mining concessions (SGU, 2012, 2018, 2020). On the ground, it is expressed in prospecting activities, test mining, and consultation meetings with land users and local communities whose future will be affected if new mining commences.

To many residents in the inland communities of the region, future visions of mining may be a promise of employment opportunities and revitalization of settlements otherwise subject to depopulation. To others it may represent a risk for local livelihoods and lifestyles, and a threat of environmental degradation. Social resistance movements, opposing mining projects, have been growing across northern Fennoscandia, organized by a variety of actors from local concerned residents and entrepreneurs to Indigenous and non-Indigenous reindeer herding communities (Mononen & Suopajärvi, Reference Mononen and Suopajärvi2016; Lépy et al., Reference Lépy, Heikkinen, Komu and Sarkki2018; Beland Lindahl et al., Reference Beland Lindahl, Johansson, Zachrisson and Viklund2018; Zachrisson et al., Reference Zachrisson and Beland Lindahl2019). In the public debate, such conflicts have been pointed out as an important factor explaining what the mining industry considers to be too slow permission processes for prospecting and mining, at a time when more minerals are needed to facilitate a global transition to green energy.

A recurring feature in the discourse of competing actors in mining conflicts in the Fennoscandian Arctic is the use of narratives. These are typically about the past and of historical remains, and their purpose is to support competing visions of the future. In this chapter we analyze such practices using the concepts of history making and heritage making. The history and heritage making we analyze concern industrial society. In research and in cultural heritage practice, this field emerged in Britain in the 1950s and developed in the western world in the decades that followed. In Sweden, industrial heritage has increasingly become part of cultural heritage practice since the 1980s. Industrial heritage has been regarded as a tool to bring new life to de-industrializing industrial towns and to support local identity – in other words, to provide societal values out of legacies from the past (Nisser, Reference Nisser1996; Isacson, Reference Isacson2013). In this chapter we will nuance this altruistic understanding of industrial heritage by exploring how actors with competing interests use the industrial past and its remains to build the futures they desire. The aim of the chapter is to understand the role of history and heritage making in conflicts regarding new mining projects. How do competing actors in conflicts connected to mining construct heritage and narratives about history, and why? What are the outcomes of such practices?

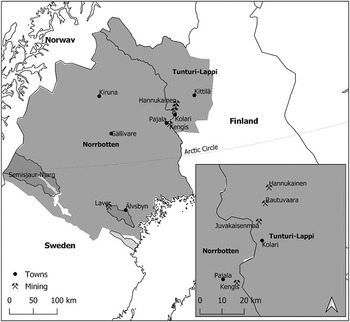

We try to answer these questions by comparing history- and heritage making in two mining regions that have undergone de-industrialization and are subject to re-industrialization: Laver in the Pite river valley in Sweden, and Hannukainen in Kolari municipality in Finland (Figure 10.1). Laver, in Älvsbyn municipality, was a mining settlement. The Swedish mining company Boliden built and operated it between 1936 and 1946. After closure in 1946, the company dismantled the town. When global demand for metals began to surge in the early 2000s, Boliden developed plans to start a new mine at Laver on a fairly large scale. The new project has generated hope for regional economic growth as well as concern for environmental degradation and disruption of Indigenous reindeer herding (Lawrence & Kløcker Larsen, Reference Lawrence and Kløcker Larsen2019).

In Kolari municipality in Arctic Finland, the mining company Rautaruukki Oy first started mining in the underground Rautuvaara mine in 1962 and then in the nearby Hannukainen open pit mine in 1978. Outokumpu Oy owned the mine until mining ceased in 1990. A concentrator plant was kept in operation until 1996 (Pelkonen Reference Pelkonen2018). At the beginning of the 2000s a European exploration and mining company, Northland Resources S.A., planned to re-open the Hannukainen open pit mine, just as in Laver but on a remarkably bigger scale. This became the subject of fierce controversy with local opponents as well as advocates of mining.

Actors on both sides in the controversies have constructed narratives about mining history and connected them with material remains in order to strengthen their positions. In this chapter we will analyze the controversies using concepts from the field of critical heritage studies. We will use the term heritagization, or heritage making, to describe the practice of ascribing historical values to a region, a place, and remains from the past – material and immaterial. We will pay attention to different forms of heritage making. One is official heritagization, meaning processes in which state agencies ascribe heritage values to historical remains and protect them by law. Another is unofficial, when non-state actors, often representatives of local communities, ascribe heritage values to remains and protect them by other means (Harrison, Reference Harrison2013; Sjöholm, Reference Sjöholm2016). A third category is corporate heritage making, when companies ascribe heritage values to their own past (Avango & Rosqvist, Reference Avango, Rosqvist and Nord2021). We will also use the concept of history making, when we can identify the wider process of establishing a particular understanding of the past, often as part of heritage making.

Laver: The Rise and Fall

The Laver area has been inhabited for thousands of years, since the inland ice retreated. The moorlands there are rich in lichen resources. For this reason, the area in and around Laver has been important for Sámi herders whose reindeer graze there during the winter. Archaeological remains reveal that Sámi, now organized in the Semisjaur Njarg Sámi reindeer herding community (RHC), have been part of the region for hundreds of years, and that the area has been used for small-scale farming and forestry for a very long time. Thus, the Laver area forms an important part of the cultural heritage of the Sámi people and of the historical small-scale use of resources that was carried out before industrialization.

There are several factors explaining why Boliden established the copper mine and mining settlement Laver in 1936. The first were concerns within Swedish industry and politics regarding access to metals after the First World War, which had disrupted imports of metals from abroad, causing disruption of production in several branches of industry (Vikström, Reference Vikström2017). To improve access to key metals necessary for Swedish industry, the Swedish state and corporate actors conducted surveys for minerals, particularly in inland areas of the north. The mining company Boliden was formed in the wake of these prospecting activities, and in 1929, Boliden surveyors found copper at Laver. In the early 1930s, the company mapped the mineralization and test mined it. The company was at first hesitant about starting up a mining operation. The size of the rich part of the mineralization was unknown and the cost of establishing a mine was high. The company leadership eventually decided to establish the mine, due to a lack of copper ore at the company’s large smelter facility at Rönnskär. With larger volumes of copper ore available, Boliden would be able to extract more gold from combined gold-copper ores from its other mines in the north (Alerby, Reference Alerby1994).

The mine and settlement were established on a forested hillside and valley floor. The production line for mineral extraction consisted of an open pit mine and an underground mine. The above-ground production line consisted of a hoisting tower, an ore crushing plant, and a concentration plant. Beyond this complex was a large tailing pond in which the company dumped sand from the concentration plant. In other segments of the landscape the company accumulated piles of waste rock (Figure 10.2).

The settlement was built with a high standard of living in order to attract miners to move there for work. The design was commissioned to John Åkerlund, the architect who had designed Boliden’s mining towns in other parts of the Swedish north. The Laver settlement consisted of buildings for housing, one to four stories high, all with central heating. It had shops, hairdressers, a community house with cinema, café and a library, a post office, dance arena, restaurant, and a fire station. When fully built the settlement consisted of thirty-one buildings out of which twenty-three were housing units, home to more than 200 inhabitants.

Mining operations at Laver became short-lived, however, due to several reasons. First, from the beginning of the 1940s the mining operations revealed that the body of relatively rich copper ore became thinner the further and deeper the mining operations advanced. For this reason, the company was unable to mine at the same speed as before. At the same time, from 1941 to 1946, the world market prices for copper decreased, particularly after the end of the Second World War. For these reasons, in 1945, the company reported a 500,000 Swedish Krona deficit and decided to close Laver the following year (Alerby, Reference Alerby1994).

Laver: The Afterlife

Without the mine, Boliden had no intention to maintain their settlement at Laver, and the inhabitants needed to find other jobs. The company dismantled all buildings, moving some of them to new locations. By May 1947, Boliden had finished this process. Up until today the remains from the mining past at Laver have lingered on – foundations from buildings and production facilities, as well as waste. Boliden had extracted 1,573 million tons of copper ore and generated waste rock piles as well as a dam containing 1,2 million tons of tailings, located in a valley downhill south of the former mine, covering an area of 12,2 ha. The tailing impoundment contained several toxic materials (Ljungberg & Öhlander, Reference Ljungberg and Öhlander2001; Alakangas, Öhlander, & Lundberg, Reference Alakangas, Öhlander and Lundberg2010). These, as well as the former settlement, slowly fell out of attention in the years following the closure of Laver. The forces of nature continued to interact with the remains from the former mining operations. During the spring melting seasons in 1951 and 1952, the walls of the impoundment eroded away and as much as a quarter of the tailings (Ljungberg & Öhlander, Reference Ljungberg and Öhlander2001) floated out into the water system downstream. According to Alakangas et al. (Reference Alakangas, Öhlander and Lundberg2010), water running through the tailings was led into a former clarification pond. It took another twenty years before any attempts were made to deal with the toxic waste at the site. Over this period, erosion had dug deep ravines into the released waste. In 1974, bulldozers were used to smooth these out. The tailings were covered with lime and fertilizer and seeded with grass (Ljungberg & Öhlander, Reference Ljungberg and Öhlander2001), and a new wall was constructed three kilometers downstream from the dam that broke (Bast & Schück, Reference Bast and Schück2019). Despite these efforts to contain the tailings, substantial amounts of toxic waste continued to be released annually into the waters: cadmium, copper, sulphur, and zinc (Alakangas et al., Reference Alakangas, Öhlander and Lundberg2010). Even into the 2020s, Boliden conducts work to contain and monitor the waste in the valley south of Laver.

While the residues from the mining process at Laver have remained a challenge for Boliden and responsible state agencies, the remains of the former settlement became subject to official heritage making. This was a result of a growing interest in industrial history from the late 1960s in Sweden, in particular working-class history, and in preserving built environments of industrial society as cultural heritage. Through the 1990s and early 2000s, this interest was institutionalized when the National Heritage Board of Sweden launched programs to include industry in the sphere of heritage protection (Isacson, Reference Isacson2013).

In 2004, this program reached Laver, when the cultural heritage department of the Norrbotten County Administrative Board, together with Norrbotten county museum, placed signboards there. The signboards contained photos of the buildings that used to stand on the house foundations, together with texts about the history of the settlement and the buildings. The texts contained a mix of historical facts and narratives about work, everyday life, and production at Laver. The narratives were about pioneering, welfare, quality of life, and faith in the future. The phrase “Welcome to Laver! Walk through Sweden’s most modern society” captures the nostalgia and communicates a sense of pride over a short-lived industrial wonder. The signboard text highlights how the mineworkers and their families had a strong sense of community and how Boliden provided workers with the possibility to have their own community house with the space for clubs, cinema, dance poll, coffee shop, and library. Only one signboard, located by the edge of the open pit mine, focuses on the history of the mining operations. None of the signboards narrate the history of the environmental consequences of the mine and its afterlife.

So, when Boliden re-established its interest in copper mineralization at Laver, the site was a concern for several categories of actors. On the one hand, there was the mining company and the environmental department of the Norrbotten County Administrative Board, who were responsible for dealing with the toxic legacies of the former mine. On the other was the cultural heritage department of the same county administrative board and the Norrbotten county museum who worked with the site and valued it as cultural heritage. Another central actor in the area was Semisjaur Njarg RHC. The Sámi reindeer herders had continued to use lands in the Laver area for winter grazing through the decades after Boliden closed. Another major land user has been the forestry companies. Since the 1950s the forests around Laver have been significantly affected by industrial logging. At the beginning of the 2000s, Pite river was pointed out as a Natura 2000 area. In the management plan it has been concluded that the environmentally harmful leakage from the old Laver mine needs to be minimized to prevent further damage to the sensitive aquatic environment (Länsstyrelsen i Norrbottens län, 2018).

Laver: The Re-birth

In addition to environmental remediation work, Boliden carried out explorations of mineral resources in the Laver area during the 1970s and the 1990s. Driven by the increasing demand for minerals, Boliden restarted exploration in 2008, and in 2014 the company submitted an application for a mining concession for Laver to the Mining Inspectorate. In their environmental impact assessment (EIA), the company described the planned mining activities and their consequences for the environment. The full extent of the proposed mining project would cover an area of approximately 46 square kilometers, including an open pit mine and all installations (Eriksson & Lindström, Reference Eriksson, Lindström, Hämäläinen and Michaelson2014). If the project is realized to the extent described in the application, it would become the largest mining site in Sweden and one of the largest in Europe. The main reason for this is the relatively low mineral concentration, approximately 0.21 percent, which means that relatively large amounts of ore need to be extracted, most of it ending up as waste rock and concentration plant sand. Figure 10.3 compares the extent of the old Laver mine, which closed in 1946, with the new mine Boliden applied for, which is significantly larger.

Boliden has incorporated the history of Laver to become part of the efforts to gain permission and acceptance for their new mine. In public information about the project, Boliden has described the company’s long history of involvement in the area and underlined its historical record of taking social, environmental, and economic responsibilities. Boliden has described their model society with state-of-the-art housing and central heating as the most modern industrial settlement in Sweden. Boliden has also described how their dam broke in the 1950s, and how the company handled this situation (Boliden 1 and 2). The narratives convey the image of a company that took responsibility in the past and thereby can be expected to do so in the future. Boliden has also declared its intention to preserve the material remains of their former mine as a cultural heritage site – a site to bring visitors to, in order to learn about the history and the future of Laver (Anonymous, interview by Pashkevich, Älvsbyn, October, 2019). This is an example of corporate heritage making, which together with Boliden’s use of history is part of the company’s effort to gain social acceptance and permissions for a new mine.

Besides Boliden, there are also other actors who have used the history and material remains of Laver to build support for a new mine, in particular actors within Älvsbyn municipality to whom the potential economic and social spin-offs of Boliden’s project, including job promises, are values of utmost importance. To these actors, old Laver represents a period in the past when the region prospered, a period that Boliden will bring back to life, a reawakening of the phoenix. Although recognizing the environmental impacts from the historic mine, they argue that the dam break never led to any serious poisoning of the ecosystem. Instead, they place the environmental impacts of the historic mine in a narrative working in favor of the new mine, the argument being that the area has already been heavily affected by mining and forestry. In other words, the new mine will not impact any pristine environment (Anonymous, interview by Pashkevich, Älvsbyn, October, 2019).

Municipal actors have also argued that Boliden has a history of maintaining a trustful relation with Sámi reindeer herders, which will contribute to solving land use conflicts between the reindeer herders and the mining company. Boliden’s long history of presence as a mining company in the region means that the company already knows how to “treat these questions with respect and also in connection to the Indigenous issues.” The continuity and good will of the company also promises a good future relation to workers and local inhabitants. To these supporters of the new mine, history holds promises for Älvsbyn to become the next “mining municipality” of Sweden (Anonymous, interview by Pashkevich, Älvsbyn, October, 2019).

The opponents of Boliden’s proposed mining project, including Sámi reindeer herders and environmental groups, also relate to history and heritage. The proposed Laver mine would be located within a winter grazing area used by the family group of Tjidjack. According to Boliden’s EIA, their planned mine would result in the loss of that grazing area. However, Semisjaur Njarg RHC has argued that the company has underestimated the impacts on reindeer herding, because of shortcomings in the process of developing the EIA. A community-based impact assessment, in which Semisjaur Njarg participated, concluded that the mine would have major impacts on their reindeer herding, which is why the RHC oppose Boliden’s plan (Lawrence & Kløcker Larsen, Reference Lawrence and Kløcker Larsen2019). In their argument against a new mine, Semisjaur Njarg has used land use history and its material representations in the landscape. They highlight how their ancestors have utilized the landscape through history, to substantiate their deep relation to the land. They also point out that there are cultural-historical remains that give evidence to longstanding Sámi use of the area, such as old huts and dwelling hearths, and emphasize how these remains remind today’s reindeer herders in Laver that their family and relatives “have been here for hundreds of years.” In other words, to the reindeer herders, they have a heritage in this area that should be preserved and managed for the benefit of future generations. This is an example of an unofficial heritage making, providing building blocks of a longer and substantially different narrative about the past, an understanding of the region’s history that is hard to harmonize with a future in which these lands would become one of the largest industry areas in Sweden. It should be noted that the material remains that the RHC refer to are also an official heritage site, defined as remains of Sámi land use by heritage expertise and protected by Swedish heritage legislation.

Semisjaur Njarg’s line of reasoning is an example of a broader use of historic arguments by RHCs in ongoing debates in Sweden concerning Sámi land rights. It relates to the historical land use of Indigenous peoples. The Swedish Supreme Court has elucidated that Sámi land rights are based on the long-time use of land, and that these rights therefore should be protected as property rights within the Swedish legal system (Swedish Supreme Court, 1981, 2011, 2020). However, even if the character of Sámi land rights has been elucidated through case law, Sweden has regularly been criticized by international human rights institutions that the Sámi people have too little influence over the issues directly involving them, and that their land rights have not been implemented adequately in the Swedish legal system (CERD, 2018, 2020). The Sámi reindeer herders argue that their long-time use of land needs to be accepted and implemented in the Mineral Act and other legislation. Thus, history and cultural heritage, as described by Semisjaur Njarg in the Laver case, are also central aspects of this ongoing debate about Sámi land rights in Sweden (Allard & Brännström, Reference Allard and Brännström2021).

In addition to the RHC, there is a growing movement in Älvsbyn municipality engaging in ongoing discussions regarding the future of mining in Laver. Pite Älvräddare (in English: Saviors of Pite river) is an organization that is part of the national NGO “Swedish Society for Nature Conservation.” The group was formed in 2015 in response to Boliden’s mining plans. As they are concerned about potential environmental risks, they have worked to build opposition to the new mine, also by history and heritage making. To the River saviors, Boliden’s efforts to deal with the environmental impacts of their historic mine, that is, the tailings outwash from the 1950s, is an act of “greenwashing,” meant to pave the way for gaining the necessary permits for their new mine. They argue that the environmental impacts from the historic mine provide evidence that the new mining operations could have catastrophic consequences for water quality, not only for the surrounding territory of the mine, but for the whole Pite river basin downstream from the mine, including drinking water for the town of Piteå with a population of more than 40,000 inhabitants (Anonymous, interview by Avango, Pashkevich & Rosqvist, Älvsbyn, October, 2019). The risk, they argue, will increase with climate change-induced increase of precipitation, which could force a release of toxic water from the tailings of a future mine.

The group also brings local and regional politicians to the historical remains of the old Laver mining area, along with groups of allied environmentalists, to show material evidence of negative environmental impacts of mining operations. To them, the historical remains of Laver prove that even after almost seventy years, the consequences of mining remain and will remain for many centuries to come. Their strategy can be seen as another example of unofficial heritage making, serving as a resource for building counternarratives about the relation between past and future mining. Interestingly enough, the river saviors do not focus their visits on the remains of the mining settlement, but instead on the remains of the tailing dams that collapsed in the 1950s (Anonymous, interview by Avango, Pashkevich & Rosqvist, Älvsbyn, October, 2019). In other words, they utilize another part of the story of the industrial past and a different material representation of that history – a history and heritage that official and corporate heritage makers have chosen to leave undercommunicated.

Hannukainen: The Rise and Fall of Mining

Kolari municipality is in the Swedish-Finnish cross border region at the Torne River Valley. This region formed a historically and culturally uniform area belonging to the Kingdom of Sweden until the formation of the Grand Duchy of Finland, an autonomous part of the Russian Empire in 1809. Due to this, Finland shares its early mining history with Sweden. Quarrying of iron ore began in Finnish Lapland in 1662 with the exploitation of Juvakaisenmaa along the river Niessajoki in the current municipality of Kolari. Here, small-scale mining continued sporadically until 1917, the same year Finland declared independence. The ore was processed mostly in the ironworks of Kengis (Köngäs) in the current municipality of Pajala in Sweden. Kengis operated until 1879 (Puustinen, Reference Puustinen2003; Finnish Heritage Agency, 2021; GTK Finland, 2021). Furthermore, the Kolari area provided charcoal for Kengis (Kerola et al., Reference Kerola, Heiskari, Koskela and Mansikka2010). The burning of coal is depicted on the current coat of arms of Kolari, recalling the municipality’s long history of mining.

In the second half of the twentieth century, more deposits of iron were discovered in Kolari, and a new mining era began in Finnish Lapland. The most notable mining development was the ironworks and underground mine of Rautuvaara (1962–1988), as well as a concentrator plant for the nearby Hannukainen open pit mine (1978–1990). Both mines were operated by a state-led mining company, Rautaruukki Oy. Mining had considerable local economic, social, and environmental impacts in Kolari. Both mines had an important role for local employment by generating 250 well-paid jobs (Alajärvi et al., Reference Alajärvi, Suikkanen, Viinamäki and Ainonen1990) with at most 143 workers in 1976 (Figure 10.4). In addition, a wide road and the northernmost train station in Finland was built with a railroad connection to Kolari and finally to Rautuvaara ironworks in 1973 (Alajärvi et al., Reference Alajärvi, Suikkanen, Viinamäki and Ainonen1990). The nearby Äkäslompolo village in Kolari, near the mining area, got its first streetlights.

Figure 10.4 Number of workers in Rautuvaara (from 1961) and Hannukainen (from 1978) mining sites and number of nights spent in accommodation facilities (excluding camping sites) in the province of Lapland and the municipality of Kolari. Tourism in Kolari began before 1993 but data was published only from 1993.

The time when the mines operated was described by locals as a time of prosperity, especially for the municipal center of Kolari (Komu, Reference Komu2019). The mining company offered housing, public services, and arranged social activities (Alajärvi et al., Reference Alajärvi, Suikkanen, Viinamäki and Ainonen1990), as was the custom at the time among big industrial companies in Finland (Hentilä & Lindborg, Reference Hentilä, Lindborg, Hentilä and Ihatsu2009). Most of the local people working in the Hannukainen and Rautuvaara mines were from the southern part of the municipality, even though the mines were in its northern part. While the northern villages could attract tourists with their fells, the southern villages were left with hard work in forestry and agriculture, hardly ideal for their northern climate, which could explain why the mine attracted workers mainly from the south (Komu, Reference Komu2019). By 1990, both mines were closed due to poor profitability, even though the Rautuvaara mine had received financial support from the Finnish state. To object to the closing of the mine, a petition with over 5,000 names was collected in Kolari (Alajärvi et al., Reference Alajärvi, Suikkanen, Viinamäki and Ainonen1990). The southern part of Kolari took the hardest hit and was left with nothing to replace the loss of an income from industry. As it was described by the locals, shops were closed, apartments left empty, and people moved out.

Hannukainen: The Rise of Nature-Based Tourism

After the closing of Rautuvaara mine in 1988 and Hannukainen mine in 1990, the sites were only lightly restored. Locally, it was wondered why the company Rautaruukki Oy wanted to maintain the sites in good condition, and it was rumoured that plenty of ore was left unextracted. After closure, the open pits in Hannukainen and shafts of Rautuvaara were left to become filled with water, and both sites included waste rock storage. The Rautuvaara mining site also consists of an underground mine, tailings, a settling pond, and a reservoir (Kivinen, Vartiainen, & Kumpula, Reference Kivinen, Vartiainen and Kumpula2018). While in operation, mining activities created disturbance to reindeer herding (Bungard, 2021) and often caused the death of reindeer in train and truck accidents during the transportation of the ore to the processing facilities (Heikkinen, Reference Heikkinen2002: 181–182). According to local herders, reindeer also drowned in tailing ponds that were not fenced. However, after the closure of mining operations, the former mining areas remained deteriorating in the landscape, but there are speculations of potential impacts on nature from the waste rock and tailings of the Rautuvaara mine (Närhi et al., Reference Närhi, Räisänen, Sutinen and Sutinen2012; Pelkonen, Reference Pelkonen2018).

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the Hannukainen site was mostly used for small-scale gravel extraction for construction needs and the old mining infrastructure for small-scale businesses. However, the contributions to local infrastructure by the mines facilitated the growth of nature-based tourism in the northern part of the municipality, which saw the emergence of tourism activities as early as the 1930s, making it a “traditional” livelihood in its own right in the region. The first tourists arrived in the northern fell area and in the Äkäslompolo village in Kolari to enjoy local skiing. The interest of tourists for this region also grew with the creation of the Pallas-Ounastunturi National Park in 1938. The residents in northern villages slowly began to switch from agriculture, fishing, and reindeer herding to small-scale homesteads. While tourism continued to be a small business in the Kolari municipality, the first transitions to full-time tourism happened in 1966 (Niskakoski & Taskinen, Reference Niskakoski and Taskinen2012). From the 1980s, tourism in the area started to noticeably grow, and Äkäslompolo began its development into a tourism village, rarely found in Finland. Along with the big tourism companies, there are still many small homestays in Äkäslompolo, often run by the third generation of tourism entrepreneurs (Komu, Reference Komu2019).

Nowadays, tourism is the most important and growing livelihood in Kolari (3,931 inhabitants in 2021, Statistics Finland, 2021), and the municipality’s public image and economy rely heavily on nature-based tourism. As an example, 48 percent of the municipality’s economy and 40 percent of employment came from tourism in 2011 (Matkailun tutkimus- ja koulutusinstituutti, 2013). Ylläs ski resort center has the fourth biggest annual revenue of all ski resorts in Finland (Jänkälä, Reference Jänkälä2019). Pallas-Yllästunturi National Park2 is the third biggest and the most popular national park in Finland with 563,100 visitors in 2020 (Metsähallitus, n.d.). The critical starting point here is that the Hannukainen mine is located 25 kilometers northeast of the municipal center of Kolari, but only 8 kilometers from heartlands of local nature-based tourism locations and the tourism center of Ylläs and the village of Äkäslompolo.

Re-opening Hannukainen: Mobilizing the past

During the 2000s, there have been two efforts made by two different companies to begin mining in the Hannukainen site. However, both efforts are related to and were built from the arguments that refer to a continuity of local mining heritage. In 2005, the European exploration and development company Northland Resources S.A. began exploring the Kaunisvaara area in Sweden, and the Hannukainen site in Finland, for the purpose of re-opening the mine. However, this effort came to an end in 2014, when Northland Resources S.A. declared bankruptcy. However, in 2015, a new company titled Hannukainen mining Oy was established, and it essentially builds its rhetoric from the ground “of being local.” The founder of the mother company Tapojärvi has its roots in the region in a namesake village and a lake close by. Their plans regarding Hannukainen continue to this day, even though locally there are suspicions that question the company’s ability to finance and operate a mine. In addition, processing the ore and tailings at the Rautuvaara site is a part of the mining plans of Hannukainen Oy, and this sets the current “reopening” plans in another kind of historical continuum: locally feared cumulative legacies of several previous mining cycles (Närhi et al., Reference Närhi, Räisänen, Sutinen and Sutinen2012; Howett et al., Reference Howett, Salonen, Hyttinen, Korkka-Niemi and Moreau2015; Pelkonen, Reference Pelkonen2018).

Due to the impacts of the first mining period in terms of employment and other societal values, many locals consider mining as a cultural heritage: an old and valuable part of local identity and history. The traces and memories of rising living standards regarding previous mining cycles are widely recognized in the municipality, but so are the values of tourism and reindeer herding, and of nature preservation in general. In that regard, Komu (Reference Komu2020) stated that the dilemma is about conflicting visions of how to “pursue the good life in the North.” It can be claimed that the battle is also between reclaiming, understanding, and defining which cultural heritage of the region should be prioritized and secured for local wellbeing. The question is: How can the continuity of nature-based tourism, reindeer herding, nature conservation (especially salmon spawning rivers), Sámi heritage sites (Kirkkopahta, Pakasaivo), and industrial development be reconciled for the future (Northland Mines Oy, 2013)?

The point of view of the Municipality administrations is clear, and they continue to be supportive of the mining plans (Sivula, Reference Sivula2021). In the previous municipal strategy, Kolari was characterized as a “mining and tourism municipality” (Municipality of Kolari, 2012). However, tensions between all local livelihoods, reindeer herding, tourism, and mining, have a long temporal continuum and have reflected even political leanings within the municipality. Tourism entrepreneurs feel that their livelihood never gained much respect from the southern part of the municipality or from the local government compared to the prestige given to mining. An opposition alliance against “reopening” the Hannukainen mine has been formed around the village of Äkäslompolo in recent years and especially a party of local tourism entrepreneurs and second-home owners. Finally, also Muonio Reindeer Herding Cooperative (RHC Paliskunta) joined the alliance, even though in previous years they had preferred to negotiate for better terms to keep up good relations with the other people trying to earn their living in the municipality (Komu, Reference Komu2020). In 2017, the herding community gave a public announcement on a Facebook group Pro Ylläs, where they expressed their opposition toward the planned mine. Their public announcement stated that the land use planning decisions made by the local government would designate an area for mining that is currently being utilized by reindeer herding but the decision was made without negotiating with the herding community (Pro Ylläs, 2017). In addition, a petition against the project has been established that has garnered over 50,000 names (Pikkarainen, Reference Pikkarainen2019), along with another Facebook group “Ylläs ilman kaivoksia” (Ylläs without mines) and a webpage “Pro Ylläs – Ylläs ilman kaivoksia” (www.proyllas.fi), and the tourism entrepreneurs took part in a fund-raising campaign to hire experts for the planning process (Similä & Jokinen, Reference Similä and Jokinen2018).