Weary from war with the formerly enslaved rebel army and having lost thousands of French troops to fighting and yellow fever, by the end of 1802, the infamous expedition of General Victoire Leclerc to reimpose slavery in Saint-Domingue was failing. Approaching death himself, that fall Leclerc sent several desperate letters to the mainland requesting additional resources and reconsideration of the mission, including one in which he pleaded:

We have … a false idea of the Negro … We have in Europe a false idea of the country in which we fight and the men whom we fight against.1

The statement reads as a deathbed confession of a military incursion gone embarrassingly awry in part from having underestimated enemy forces. But a deeper excavation of Leclerc’s sentiment reveals a potential moment of awakening from Europe’s three-centuries-old ontological belief in the supposedly inferior nature, identity, and intellectual capacity of the “negro.” As Michel-Rolph Trouillot (Reference Trouillot1995) has argued, until – and indeed, even after the Haitian Revolution, Europeans failed to conceive of Africans as humans, as thinkers, as planners, or as revolutionaries. Early nationalistic chauvinism embedded in both early Christianity and capitalism fueled the reimagination of African polities, cultures, and individuals into a flattened, singular “negro,” or black identity void of any distinctions (Robinson Reference Robinson1983: 99–100; Wynter 2003; Bennett Reference Bennett2018). Cedric J. Robinson’s (Reference Robinson1983) now foundational Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition has offered that the “negro” was an invention of racial capitalism, manufactured through Christianity, commodification and the transatlantic slave trade, and enslavement in the Americas.

Enslavers’ imposition of an inferior racial identity did little to alter the self-defined identities of diasporic Africans who, in many ways, retained knowledge of and appreciation for who they were and the ways they understood the world – despite the traumatic experience of the Middle Passage and enslavement. Africans embodied their own biographies, histories, and worldviews that shaped their human activities – especially within political, economic, and military realms – and this ontological and epistemological core with which Africans operated represented the source of their opposition to racial capitalism (Robinson Reference Robinson1983). Scholars have increasingly given attention to the dimensions of West African and West Central African cultural, religious, militaristic, and political influences on the Haitian Revolution (Thornton Reference Thompson1991, Reference Thompson1993b; Gomez Reference Gomez1998; Diouf Reference Diouf2003; Mobley Reference Mobley2015). This turn provides a growing baseline of historical data that problematizes previous beliefs that France alone bestowed Enlightenment ideals upon enslaved African people. Reading the archives of enslavers’ records that labeled captives according to their geographic locations – though oftentimes incorrectly – reveals that African ethnicities and cultural identities were not only linked to specific locations of origin, but to political projects.

Africans were not able to fully retain entirely cohesive social, political, or religious structures due to the trauma of separation from their homes and the Middle Passage; but they re-created elements of their institutions and transmitted them through interactions on plantations, in ritual spaces, in self-liberated maroon communities, and in the bellies of slave ships. Prior to the colonial situation, African captives began bonding around coping with the horrifying conditions of the Middle Passage. The long voyages on foot or in small river boats from hinterlands to coastal port cities, and the waiting period in slave castles at the ports, could take several months to a year. In addition, slave ship voyages across the Atlantic Ocean also took up to three to four months. Ship captains, traders, and sailors tightly packed captives into ships, usually head-to-foot to fit as many people as possible into the ship’s belly. Food was meager and the sanitary conditions were loathsome. The Middle Passage was a harrowing experience where physical abuse, disease, and death; psychological disorientation; and sexual exploitation were ubiquitous. Captives commonly attempted suicide and at times collectively revolted on the ships (Richardson Reference Richardson and Diouf2003; Smallwood Reference Smallwood2008; Mustakeem Reference Mustakeem2016). Interactions between “shipmates” on the way to the ports and on slave ships were the only sources of human affirmation, and the beginnings of the social ties that would spawn collective identity formation and cultural production after disembarkation (Mintz and Price Reference Mintz and Price1976; Borucki Reference Borucki2015).

This type of violent extraction from families, communities, and societal structures would have stimulated in slave trade victims an affinity for their real (rather than mythical) homelands that was the basis of their attempts to actively preserve, re-formulate, or construct oppositional consciousness, identities, network relationships, and cultural and religious practices to maintain self-understanding and integrity in host societies that were hostile to their presence (Vertovec Reference Vertovec1997; Shuval Reference Shuval2000; Butler Reference Butler2001; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2005; Hamilton Reference Hamilton2007; Dufoix Reference Dufoix and Rodarmor2008). As such, maintaining a sense of self and creating community relationships, behaviors, norms, and ideologies to affirm the collective was essential to African Diasporans’ survival and acts of resistance against enslavement (Hamilton Reference Hamilton2007: 29–31). African ethnic or “New World” identities that were linked to specific cultural, religious, and racial formations influenced several collective action rebellions throughout the Americas. Rather than assume these formations were “backward-looking” or somehow lacking progressive ideals as Eugene Genovese (Reference Genovese1979) suggested, I argue that rebellions among the enslaved and maroons were based on the political, economic, and cultural practices of those who themselves were avoiding capture or otherwise resisting the violence of the transAtlantic slave trade. Rebellions and revolts like Tacky’s Revolt in Jamaica and the Haitian Revolution were indeed progressive, transformative factors that altered the course of European struggles for hegemonic power (Santiago-Valles Reference Santiago-Valles2005) and broadened discourses around freedom, equality, and citizenship.

Who were the “negroes,” “rebels,” “brigands,” “insurgents,” and “masses,” as C. L. R. James ([1938] Reference James1989) referred to them, of the Haitian Revolution? From where did they originate, what was the shape and character of the social forces into which they were socialized, and how did elements of their African origins inform collective action? This chapter attempts to contextualize forms of resistance tactics that appeared in Saint-Domingue from the perspective of Africans who “lived in their ethnicity as much as anyone else” (Winant Reference Winant2001: 55), and therefore were influenced by their respective socio-political and cultural worldviews. Though it was a French and white creole colony in name and political economy, the social world of Saint-Domingue was essentially African. Approximately 90 percent of the colony’s population was black, and over two-thirds of those black people were of immediate African extraction. Enslavers purchased or kidnapped captives from several African societies that practiced indigenous forms of enslavement, although these systems were qualitatively different from the racialized slavery Europeans implemented in the Americas. African forms of slavery add another dimension to the socio-economic and political realities that captives lived with on the continent, and it constituted part of their collective consciousness. Yet the incongruence between African and European slaveries, the commodification that rendered human life expendable, and processes of racialization were radicalizing forces that further heightened and politicized collective consciousness. The persistent influence of African social, political, and religious formations – especially the Bight of Benin and West Central Africa – helped inform the ways enslaved people in Saint-Domingue coped with their situation and attempted to reconstruct their lives in ways that were alternative to the dictates of Western modernity.

The transAtlantic slave trade and African rulers’ responses to it were leading causes of societal transformations that affected the everyday lived experiences of women, men, and children who were either victimized by the trade in some capacity or were aware of the potential to be victimized. African state leaders increasingly consolidated power and wealth, which they gained from trading captives with Europeans. The growing chasm between the elite classes and those who were most vulnerable to capture led to conflict and revolt over the trade, making eighteenth-century African wars and uprisings an important scene of the Age of Revolutions (Ware Reference Ware and Rudolph2014; Green Reference Green2019; Brown Reference Brown2020). Discontent over the trade, warfare and upheaval, and shifting paradigms over the nature and scope of African rulers’ absolute power created space for more egalitarian political philosophies to emerge “from below” and challenge existing regimes. Politically progressive ideals sought to place limits on monarchal authority through decentralized governance, and placed higher expectations on kings to act with fairness, unselfishness, and restraint. These changing beliefs were often understood and articulated through socio-religious idioms as people attempted to rectify societal imbalances through ritual, resistance, and the development of egalitarian social forms on both sides of the Atlantic (Thornton Reference Thompson1993b). Individuals responded to the increasing encroachment of the trade by attempting to defend or fortify themselves or their communities. Africans’ discontent over violent capture and strategies for attempting to resist the trafficking process were also expressed through coastal marronnage and slave ship insurrections. Those who were unsuccessful at self-protection and funneled into the trade carried with them not only the trauma of their personal experiences, but undoubtedly held anecdotes about neighbors, kith, and kin affected by the trade and attitudes about whether they were justifiably or unjustifiably being held captive according to local custom, and for what reasons. Many of the rituals and spiritual beliefs, political ideas, and acts of rebellion that would later become prominent during the Haitian Revolution predated the Middle Passage and therefore serve as important antecedents that deserve exploration. What follows is an attempt to explicate and trace the Black Radical Tradition to Saint-Domingue, from its inception in African political formations and socio-religious worldviews, its containment and transformations due to commodification and contact with the French Atlantic slave trade, and expressions during coastal and slave ship rebellions.

Domestic African Slavery and the French Trade

Slavery was part of many African societies and was based on inequality, but it operated differently than the racialized slavery Europeans initiated in the Americas. Domestically enslaved Africans – and their labor – were a concrete form of privately-owned property and were considered subordinate family members. Despite not owning themselves or their labor value and performing labor that would be considered degrading, enslaved people typically were not denied their humanity and at times were allowed relative freedoms, social mobility, and property ownership. Various societies had their own socially constructed norms surrounding eligibility for enslavement. Captives included prisoners of war, the financially indebted, and cultural or religious outsiders. For example, those who had knowledge of the Qu’ran at areas of Senegambia could be protected from the slave trade; native-born Dahomeans were not supposed to be enslaved; and Kongolese bondspeople were typically from outside the kingdom and could be physically punished for disobedience or for being absent without prior permission.2 Buying people was a way of accumulating wealth and state officials used many of the enslaved for government or military services to increase their political power. It was relatively easy for enslavers to trade with Europeans, since they were likely to be wealthy merchants, rulers, or state officials. In exchange for European manufactured guns, alcohol, salt, clothing and jewelry, African kings and merchants sold war captives from neighboring polities, criminals, and other individuals who were most peripheral to centers of power.3 As the demands for enslaved labor on Caribbean and Brazilian sugar plantations increased and trade with Europeans became costlier, African kings resorted to waging wars to meet the demands for more captives.

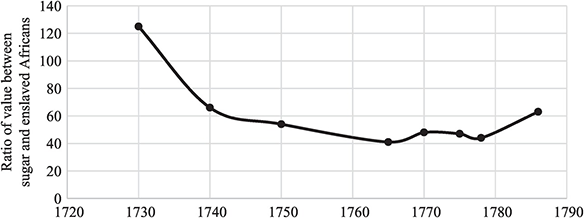

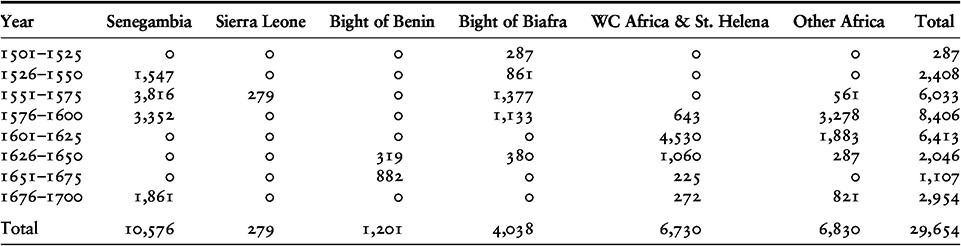

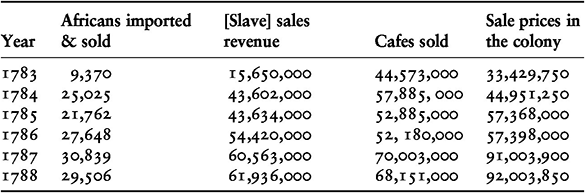

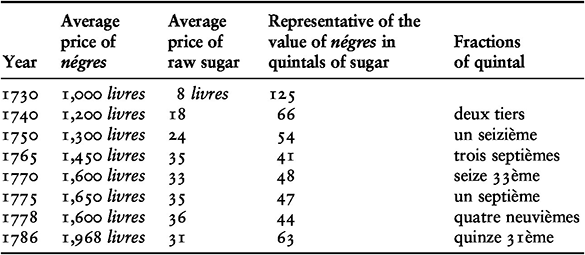

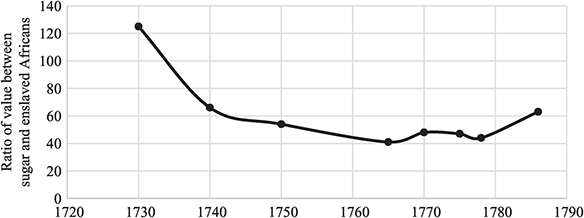

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to sustain contact with parts of Africa through trade and conquest in the mid-fifteenth century; they first explored the Bight of Benin in 1472 and were shortly followed by Spaniards who procured slaves from Portuguese and Dutch traders. With the founding of the Dutch West India Company in 1625, the French West India Company in 1664, and English Royal African Company in 1672, captive Africans quickly became the foremost form of capital – even more valuable than land or gold by the eighteenth century, according to Walter Rodney – and the international slave trade accelerated.4 The French slave trade was relatively obscure and illegal during this period. Early in the eighteenth century, French ships supplied Spanish colonies with African captives, but few of these voyages resulted in trafficking bondspeople to French territories in the Americas, leaving a dearth of French slave trading records. Before the Treaty of Utrecht officially sanctioned the French slave trade in 1713, the Dutch and English sold many Africans to French Caribbean islands, and the French took other captives during raids on English ships and territories. The number of slave ship voyages and disembarked Africans gradually increased in the early part of the century, then exploded in the 1770s and 1780s.

European slave traders relied on established commercial networks and a range of actors who facilitated negotiations, financial exchanges, and the procurement of human bodies, typically through brutal means. The levels of violence used to extract and traffic Africans to the coasts and onto slave ships cannot be understated. Sowande Mustakeem’s (Reference Mustakeem2016) Slavery at Sea has illuminated the micro-level processes of the Middle Passage, beginning with the moment of capture and ending at the point of sale at ports of the Americas, emphasizing the effects of violence, illness, and psychological despair on individual captives as well as the larger collective of captives as they witnessed traumas inflicted on others. In addition to engaging in warfare, captors leveled raids on families, communities, and villages unexpectedly, and by the eighteenth century nearly 70 percent of captive Africans had been victims of kidnapping. Though by some local conventions slavery was associated with criminality or being born within a low status group, increasing demand from plantations in the Americas during the eighteenth century meant that on the African continent, “escalating value placed upon black bodies created a threatening environment in which every person in African society, regardless of status, became a potential target.”5 It is estimated that during the eighteenth century, the French transported between 1.1 and 1.25 million captive Africans, bound for port cities of the Americas. Of those captured, nearly 800,000 embarked on ships headed to Saint-Domingue but only 691,116 survived the Middle Passage and were counted among those who disembarked.6 The loss of life during the voyages is only part of the total experience of African deaths, which also included fatalities “between the time of capture and time of embarkation, especially in cases where captives had to travel hundreds of miles to the coast … [and] the number of people killed and injured so as to extract the millions who were taken alive and sound.”7

As the trade ratcheted up around mid-century, a seemingly unending stream of Africans were brought to the colony, resulting in the enslaved population approaching 500,000 just before the Haitian Revolution, two-thirds of whom were continent-born.8 In the first half of the eighteenth century, the majority of captives were taken from the Bight of Benin with West Central Africans and Senegambians, respectively, representing the second and third most common groups. After 1750, however, French slave trading moved southward along the West Central African coast. These inhabitants became the largest proportion of captives to Saint-Domingue and were increasingly desired to labor in the colony’s quickly growing coffee industry. For example, one family in Port-au-Prince stated in 1787 that their affairs were so prosperous that the estate went from owning 5 to 36 slaves in a matter of only 18 months.9 Once a ship was financed to take sail from one of the French ports, most likely Nantes since it was the busiest slaving port, the captain took wares to be sold for African captives at the coast. Guns were one of the most highly valued trade items, as they gave the perception of technological advancement and amplified strength and power in warfare to capture more slaves; for example, a petition from a “citoyen,” Sudreau, appears to request permission to exchange African captives for 700 guns.10 The growing abundance of captives at the coast meant that prices for slaves were cheaper than in the Caribbean colonies. Eighty Africans from the Guinea coast destined for Les Cayes were bought for 800 livres, approximately half the value that planters placed on healthy enslaved adults.11 Other highly valued captives were black sailors and other ship hands, whose nautical skills and familiarity with coastal cultures could aid slave ship captains in completing transactions. One sailor, described as a “Frenchified” black, was valued at 2,400 livres, significantly higher than the average price of a Saint Dominguan enslaved person.12 In order to ensure the voyages’ profitability, ship captains procured as many slaves as possible, sometimes tarrying along the African coast and visiting multiple ports to find available human cargo, but typically slavers secured captives from one African port to reduce the length of the voyage and the probability of illness and insurrection.

Archival data show a clear dominance of African men over women during the height of the French trade to Saint-Domingue, consistent with findings from other European nations’ trading activity more generally. Between 1750 and 1791, the highest level of gender parity existed among captives from the Bight of Biafra, where 53.9 percent were male and the remaining 46.1 percent women and children. Children represented a sizable proportion in French slaving records, accounting for nearly 27 percent of captives. Lower sex ratios were often due to raiding and kidnapping, and women and children were often the victims of these activities, as seen in the Bights of Biafra and Benin areas. Higher levels of gender imbalance occurred between captives from the West Central and Southeastern African regions. This disparity, especially among West Central Africans, can be attributed to women’s value as local agricultural laborers, which kept them from being vulnerable to the trade in higher numbers. Other reasons for the low presence of women in the French trade relate to local needs for women in matrilineal societies; additionally, the hardships of the journey from the interior to the coasts made women and children less desirable to slavers.13 Such gender dynamics – as well as responses to the slave trade – varied by culture, political structure, and region. What follows is an exploration of those variations, and considerations of religion, economy and political systems in areas that were most impacted by the French slave trade to Saint-Domingue.

Political Systems, The Slave Trade, And Religion

During the height of the slave trade, several African polities were consolidating power and wealth at the highest levels, leaving communities, clans, and towns vulnerable to warfare and raids. Popular contestations to abuses of power not only influenced revolts and resistance to the slave trade, they informed political consciousness about the nature of rule, inequality, and unjust forms of slavery. As Africans from various regions encountered each other in Saint-Domingue, they found compatibility and solidarity in their experiences and perspectives on the imbalances of power and resources that resulted in enslavement. In the Dahomey Kingdom, ancestral and nature-related deities indicated the religious reach of monarchal rulers into the everyday lives of their subjects, including the enslaved. These imperial deities, as well as local spirits, migrated with people through the Middle Passage to the Americas. Other coastal African religious systems were less tolerant of the realities of slavery and informed ethical dimensions against the slave trade. Muslims at Senegambia, as well as Vili traders based at the Loango Coast, exemplify a major thrust of this chapter: that African peoples had local conceptions of slavery and the damage caused by the European slave trade, and that spiritual sensibilities informed those ideas. Yet, despite these systems of thought that opposed the fundamentally exploitative and dehumanizing nature of the slave trade, African participation in the vast commercial network allowed the European slave trade to function by relying on local knowledge and trade relationships. These and a multitude of other African-born people represent the complexity of local complicity with the trade, the power imbalances between Europeans and Africans, and opposition to the slave trade.

The Bight of Benin

According to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, deportees from the Bight of Benin comprised over 35 percent of those taken to Saint-Domingue in the early part of the eighteenth century. The French settled a trading base at Ouidah, one of the most utilized slaving ports at the Bight of Benin, a region that eventually came to be known as the “Slave Coast” due to its convenient geography and low purchase prices for captives. One of the most prolific slave trading polities at the Bight of Benin was the Dahomey Kingdom, which originated in the sixteenth century in a small, geographically dismal area 60 miles from the coast. Its capital was Abomey, but the land had little to no natural resources and the climate of the area was not conducive to habitation. The nation’s dependence on the slave trade to obtain guns pushed them towards the coast, dominating other cultural groups, such as the Yoruba-speaking Nagôs and Fon/Gbe-speaking Aradas, along the way.14 By the 1730s, Dahomey had emerged on the Guinea Coast, after having conquered Allada in 1724, Ouidah in 1727, and Jankin in 1732.15 With direct Dahomean presence on the coast, there was a steady supply of captives for the trade. The yearly number of captives from the Bight of Benin to Saint-Domingue increased from 8,577 to 10,970 between 1721 and 1730, corresponding to Dahomey’s conquest of Ouidah in 1727 (Table 1.1). Similar to West Central African conceptions that equated the slave trade to witchcraft or cannibalism, which will be discussed below, seventeenth-century recordings in Dahomey suggest some captives believed that traders would eat them. Other beliefs included the idea that “the cowry shells which were used locally as money were obtained by fishing with the corpses of slaves, who were killed and thrown into the sea, to be fed upon by sea snails, and then hauled back out to retrieve the shells.”16 The metaphors of people being eaten by sea animals or other people, or being transformed into material objects, reflected the harsh reality of the exchange between humans and commodities, and expressed widespread fear and indignation about the slave trade.

Table 1.1. Embarked captives to Saint-Domingue by African region, 1700–1750

| 1701–1705 | 1706–1710 | 1711–1715 | 1716–1720 | 1721–1725 | 1726–1730 | 1731–1735 | 1736–1740 | 1741–1745 | 1746–1750 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senegambia | 0 | 160 | 2,096 | 2,431 | 2,063 | 1,221 | 3,805 | 5,168 | 4,835 | 768 | 22,547 |

| Sierra Leone | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 177 | 220 | 0 | 397 |

| Windward Coast | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 922 | 2,164 | 395 | 3,561 |

| Gold Coast | 0 | 0 | 0 | 149 | 273 | 0 | 1,102 | 5,354 | 8,699 | 1,116 | 16,693 |

| Bight of Benin | 0 | 1,408 | 4,899 | 8,059 | 8,577 | 10,970 | 6,152 | 15,453 | 9,371 | 3,665 | 68,554 |

| Bight of Biafra | 0 | 0 | 370 | 1,027 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 320 | 484 | 0 | 2,201 |

| WC Africa & St. Helena | 0 | 0 | 840 | 2,875 | 2,993 | 593 | 3,172 | 10,809 | 13,696 | 8,956 | 43,931 |

| SE Africa & Indian Ocean | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 386 | 0 | 386 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 772 |

| Other | 607 | 0 | 1,718 | 4,412 | 1,222 | 2,238 | 2,380 | 7,157 | 6,018 | 3,240 | 28,992 |

| Total | 607 | 1,568 | 10,003 | 18,593 | 15,514 | 15,022 | 16,997 | 45,360 | 45,484 | 18,140 | 187,648 |

Fon/Gbe-speaking peoples turned to their local spirit forces, the vodun, to intervene on their behalf. The thousands of vodun at the Bight of Benin can be generally categorized into two groups: those derived from family networks, including ancestors, and founders of clans and towns; and those associated with the forces of nature such as fire, the sea, and thunder. While most vodun were based in local communities, powerful vodun attracted followers from other locales. The oldest vodun that had long-standing roots in one community received the most reverence. The snake spirit, Dangbe, was considered part of Ouidah’s royal pantheon prior to Dahomey’s emergence. People presented Dangbe with gifts such as silk, food and drink, and foreign commodities, with hopes that he would provide protection to society from outside forces. The spiritual power of the local vodun translated into social capital and political strength that could undermine imperial Dahomey’s ideological and cultural dominance, and the priests of Dangbe were nearly equivalent in power and status to the king of Ouidah. Dahomeans destroyed and ate the sacred snakes of Ouidah during their 1727 campaign to publicly demonstrate their hostility and military dominance over the people and their gods.17 Although Ouidah had suffered defeat, signaling to some the spiritual inferiority of Ouidah’s vodun, members of the conquered Fon/Gbe-speaking peoples who were exiled to Saint-Domingue maintained a close relationship with the snake spirit and became the progenitors of what would become Haitian Vodou. Oral histories reveal there was continued unrest in the 1730s and 1740s, as followers of Sakpata, a group of vodun associated with the land, were rumored to use spiritual means to plot against King Agaja in retaliation for his sale of so many of Sakpata’s adherents into slavery.18

The Dahomean monarchy responded with active measures to re-shape religious life by appropriating local vodun, while introducing new vodun from the royal lineage for public reverence to “more effectively control the followers of popular gods.”19 Members of the royal family were strictly prohibited from participating in worship of vodun outside of the king’s ancestral lineage. However, “commoner” clans – groups of royal subjects – could associate with and worship the monarch’s ancestral vodun. Dahomey’s religious consolidation helped facilitate its growing domination, and the kings’ ability to centralize and wield political, economic, and military power deeply relied on the manipulation of existing religious beliefs and practices. The kpojito queen mother, a political and symbolic position held by a woman related to the Dahomean king by birth or marriage, influenced religious relations. One of the longest serving kings of Dahomey, Tegbesu, reigned from 1740 to 1774 and was accompanied by his kpojito, Hwanjile, who is credited with re-organizing religious hierarchy in Dahomey. Hwanjile introduced several vodun to the kingdom, most notably the creator couple Mawu and Lisa, in 1740, which were ranked above all other local vodun. Mawu and Lisa represented an ideological message that power and authority came from both male and female figures, which may have helped satisfy remaining followers of Dangbe – many of whom were women who could attain priesthood and other statuses of rank, even if they were of the commoner or slave class.20 This move was instrumental in aiding King Tegbesu gain power and control over Dahomean religious life, thereby undermining the mechanisms by which protest could emerge.21

In addition to religious legitimation, the power of the slave trade bolstered Dahomey’s state-building capacity and wealth, particularly during Tegbesu’s tenure. Tegbesu personally supervised trade relations at European forts and with the Oyo Empire. But, up to and after his death, the fundamental Dahomean law that banned the sale of anyone born within the kingdom was no longer upheld, as slaves became the primary overseas export good.22 Dahomean kings lived lavishly as a result of slave trading profits, which they displayed at “customs” ceremonies where festivities included distributing food, drink, trade goods, and well as military performances.23 Figures from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database (Tables 1.1 and 1.2) help create a more complex picture of the volume of the slave trade from the Bight of Benin. There seems to have been a drop in the slave trade from the Bight of Benin between 1741 and 1750, the first years of Tegbesu’s power, then an even more drastic drop between 1755 and 1760. Though Ouidah continued to be a forerunning port for the French well into the latter half of the eighteenth century, ongoing warfare between Dahomey and the neighboring Oyo Empire between the 1760s and 1780s was a dominant factor in generating large numbers of captives from the Bight of Benin to Saint-Domingue.

Table 1.2. Embarked captives to Saint-Domingue by African regions, 1751–1800

| 1751–1755 | 1756–1760 | 1761–1765 | 1766–1770 | 1771–1775 | 1776–1780 | 1781–1785 | 1786–1790 | 1791–1795 | 1796–1800 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senegambia | 3,964 | 0 | 1415 | 2,222 | 2,306 | 1,961 | 2,248 | 7,459 | 837 | 0 | 22,412 |

| Sierra Leone | 1,301 | 263 | 1,991 | 4,487 | 255 | 1,698 | 4,083 | 6,676 | 1,644 | 0 | 22,418 |

| Windward Coast | 772 | 0 | 344 | 456 | 241 | 196 | 573 | 2,010 | 206 | 0 | 4,798 |

| Gold Coast | 1,006 | 230 | 109 | 1,377 | 1,111 | 630 | 2,145 | 8,029 | 431 | 0 | 15,068 |

| Bight of Benin | 21443 | 577 | 5757 | 12,785 | 18,423 | 18,224 | 7,926 | 30,809 | 3,366 | 0 | 119,310 |

| Bight of Biafra | 1,676 | 626 | 1,502 | 4,097 | 1,686 | 5,179 | 2,891 | 13,263 | 4,535 | 0 | 35,455 |

| WC Africa & St. Helena | 20,881 | 2,673 | 14,292 | 48,003 | 44,086 | 27,887 | 37,318 | 76,235 | 15,120 | 540 | 287,035 |

| SE Africa & Indian Ocean | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 333 | 2,189 | 2,513 | 19,473 | 4,901 | 0 | 29,409 |

| Other | 7,216 | 250 | 4,060 | 9,093 | 7,842 | 7,038 | 9,598 | 19,325 | 6,148 | 0 | 70,570 |

| Total | 58,259 | 4,619 | 29,470 | 82,520 | 76,283 | 65,002 | 69,295 | 183,279 | 37,208 | 540 | 606,475 |

The Oyo Empire and its Yoruba-speaking inhabitants trace their origin to the city Ile Ife, which was first ruled by the common ancestor and king Oduduwa prior to the sixteenth century. After being sacked by the Nupes in the sixteenth century, and later by the Bariba, the Oyo Empire reorganized itself, laying the foundation for expansion in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.24 In contrast to the centrality of monarchical power in kingdoms like Dahomey, Loango, or Kongo, the Oyo Empire was composed of smaller units of political power based in Yoruba towns that operated autonomously but were subordinate to the Oyo king. Town “chiefs” gained power through the accumulation of wealth and followers, and this power was passed down through lineage. Chiefs represented the interests of their families and followers within their wards to the king; however, members of the wards could shift allegiances from one chief to another depending on the efficacy and generosity of the latter. Many chiefs commanded the military, while a group of seven elite chiefs composed a religious council to control the spiritual sects. There was also a Muslim ward of the city of Oyo, established between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which was under the control of one of the non-royal chiefs.25 The Oyo Yoruba and Aradas had similar cosmologies, and in fact several Yoruba nature spirits, the orisha, such as Ogou, Eshu-Elegba, Olorun, Oshun, and Oshumare, were incorporated into vodun due to expansion, trade, demographic shifts, and conflict between Dahomey and the Yoruba peoples.26

The Oyo Empire went to war with Allada in 1698 and fought Dahomey in 1726–1730 in response to Dahomey’s aggressive attempts to control the slave trade at the coasts, which stood in opposition to Oyo’s commercial interests. Oyo’s campaign to provide aid to smaller nations resisting Dahomey successfully resulted in Dahomey becoming a tributary to Oyo, and Oyo supplied slaves to Ouidah through Dahomey.27 From 1739 to 1748, Dahomey again revolted against Oyo, which was not a long-term success since by the 1770s Dahomey was paying tribute to Oyo and the two empires fought alongside each other to invade smaller polities like Mahi and Badagri.28 The height of Oyo’s power was between 1754 and 1774, when the empire expanded to the north, then from 1774 to 1789, when it conquered Egbado, Mahi, and Porto Novo. Major interrelated factors that led to the rise of the empire included its military might and the use of highly trained cavalry and archers; economically it grew due to participation in the expansion of long-distance trade and commerce, most notably the Atlantic slave trade, which then financed military resources. Other captives that the Oyo empire enslaved or traded were the Oyo Yoruba, non-Oyo Yoruba, and neighbors of the Yoruba such as the Hausas, Nupe, Borgu, Mahi, and the Bariba.29

The Yoruba-speaking Nagôs were a key group from the Bight of Benin taken to Saint-Domingue. While Yoruba captives taken to Cuba were referred to as the Lucumí, in Portuguese Brazil and French Saint-Domingue, the Yoruba collectively were called Nagô.30 Archival data from Saint-Domingue’s plantation records and runaway slave advertisements indicate that the Nagôs actually outnumbered the Aradas by the end of the eighteenth century.31 There is some confusion about the origins of the term “Nagô”; historians have suggested that Fon-speakers applied the term to all Yoruba slaves and any captives handled by Oyo. Other evidence points to the Anagô as a smaller society of merchants that occupied southwestern Yorubaland, which was subject of the Oyo Empire from as early as the late seventeenth century. In the early eighteenth century, the Nagô traded slaves for firearms at Porto Novo and its towns paid tribute to Oyo in tobacco, gunpowder, European cloth, and flints.32 As a subsidiary nation of Oyo, the Nagô were dispatched to send provisions and armies led by “Kossu, a Nago chief, belonging to Eyeo [Oyo]” to assist Dahomey in raids against Bagadri in 1784. The Nagô themselves were also targets for the trade during periods of heightened warfare between Dahomey and Oyo. Nagôs were sold from Ouidah as early as 1725 and again in 1750; from Porto Novo in 1780 and 1789; and during three campaigns waged by Dahomey against the Nagôs in 1788 and 1789.33 As the Oyo Empire weakened and Dahomey ascended, between one-fourth and one-third of captives from the Bight of Benin were Nagôs/Yorubas, making them one of Saint-Domingue’s ethnic majorities whose numbers increased during the time period leading to the Haitian Revolution.34

The Nagôs’ militaristic experience, as both participants in and victims of the slave trade, seems to be reflected in contemporary Haitian Vodou, as Nagô is a significant “nation” or ethnically organized pantheon of spirits that includes important warrior-oriented deities like Ogou and Agwé.35 Combat skills acquired through the Anagô military background were essentially transferred to Saint-Domingue through war captives, traded as slaves, who later put their knowledge to use during the Haitian Revolution – for example, the rebel leader Alaou. Accounts from Cap Français in 1793 described Nagô rebels as a “valiant nation” of fierce fighters who skillfully prevented an incursion of armed free people of color and put down attempts to recruit local plantation slaves into the ranks of the free troops. Jean-Jacques Dessalines was said to have been a devoted follower of Ogou, the god of warfare and iron. After his assassination in 1806, he was deified in Vodou as Ogou Dessalines within the Nagô tradition.36 Nagô influence in the Haitian Revolution predates the “Nagoization” of nineteenth-century Brazil and Cuba in the wake of the Oyo Empire’s collapse, which brought a flood of enslaved Yoruba-speakers into the sugar-producing nations through illegal trafficking and triggered several Nagô-led slave rebellions (Barcia Reference Barcia2014). As I discuss in Chapters 3 and 8, Nagô/Yoruba conceptions of weaponry, war, and religion became a key component of enslaved people’s collective consciousness during Saint-Domingue’s pre-revolutionary era and the 1791 uprising. Their experiences with the transAtlantic slave trade as victims and traffickers would have been thrown into sharp relief in a foreign colony where slave status was synonymous with race and African origin, rather than with relationship to powerful states.

Senegambia and Other Areas

Intra-European, intra-African, and European-African conflict over control of the slave trade destabilized many coastal and interior societies and affected the regional outflows of African ethnic groups over time. In addition to the Bight of Benin Coast, the French held Senegambian slave posts at Gorée Island, near Dakar, and Saint Louis, between the Senegal and Gambian rivers. Given its geographic proximity to Europe, Senegambia was the first sub-Saharan region to establish direct commercial contact with Portugal in the fifteenth century and was one of the first leading sources of captives to Iberia and the Americas.37 At that time, the Jolof Empire controlled much of the region from the Senegal River to Sierra Leone and was composed of several ethnic and linguistic groupings including the Wolofs, “Mandingues,” and “Bambara” Mande-speakers, and “Poulards“ or Fulbe-speakers. When the empire disintegrated in the middle of the fifteenth century, several of its vassal states broke for independence, in part to determine the terms of their relationship with the slave trade and to protect their constituents from capture. Aggressive slave trading led to economic, social, and political crises such as increasing militarization and inter-state violence.38 Armed military forces known as the ceddo operated alongside oppressive regimes and unleashed violence throughout Senegambia during their raids for slaves. The kings protected the ceddo regimes as they captured their own subjects in exchange for guns and liquor, and to satisfy indebtedness to European traders.39 As a result of the rife violence associated with the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Senegambian captives were the third largest regional group brought to Saint-Domingue by the early eighteenth century (Table 1.1). Soon, Muslim clerics would lead anti-slavery religious movements at Futa Jallon and Futa Tooro that would disrupt the slave trade and influence rebellions in the Americas. By the second half of the eighteenth century, the Bight of Biafra exceeded Senegambia as the third source of African captives to Saint-Domingue. Generally lacking a centralized political structure to regulate the trade, the swampy coastal regions surrounding the Niger and Cross Rivers were particularly vulnerable to small-scale raids, kidnapping, and legal and religious justification for enslaving the Igbo and Ibibio populations.40

Gold Coast captives were not very common in the colony, and their number in the trade seems to have remained under 30,000 throughout the eighteenth century. But, as planters in Saint-Domingue’s southern peninsula struggled to keep productivity in pace with the prosperous northern and central plains, they turned to brokers who procured slaves from diverse regions. A 1790 accounting statement from the captain of the ship L’Agréable shows that several planters from Port-au-Prince, Croix-des-Bouquets, Mirebalais, Léogâne, and as far as Nippes and Jérémie purchased 26 of the ship’s 187 souls originating from Little Popo.41 These captives from Little Popo may have been counted as members of the Mina nation, who are often confused by scholars as originating from the El Mina fort in present-day Accra, Ghana, since the port town borders the Bight of Benin and the Gold Coast. Eighteenth-century people known as the Mina were often polyglots who spoke both the Fon/Gbe language of the Bight of Benin and the Gold Coast Akan language. The Mina were reputed to be excellent fishermen, gold and saltminers, and mercenaries proficient in using firearms. Mina armies were in high demand, migrating to places that called for their services including the Bight of Benin/Slave Coast, where many were captured and sold to the Americas.42

As the slave trade progressed and the French lost their West African colonies Senegal and Gorée to the British during the Seven Years War, French traders moved their bases beyond West Central Africa toward Southeastern African shores. Sofala, a province of Mozambique, was a major East African trading entrepôt, where captives were funneled into the Atlantic and Indian Ocean slave trades.43 To supply their Caribbean sugar and coffee plantations with enslaved laborers, the French exchanged firearms and coinage, and their eighteenth-century economic activities in East Africa rivaled those of the Portuguese.44 Though the number of enslaved Mozambicans and others from Southeastern African/Indian Ocean regions in Saint-Domingue was not nearly as large as those from the Bight of Benin or West Central Africa, after 1750 their numbers actually exceeded Senegambians, Biafrans and others from less exploited regions (Table 1.2). Familiarity with the Arabic language and Islamic beliefs and practices was a commonality that connected significant portions of Senegambia and Sierra Leone as well as Mozambique, since the religion had been a mainstay in Mozambique from as early as the ninth century. It is highly likely that enslaved Mozambicans who also were of the Islamic faith were sold to Saint-Domingue.45 Islam influenced anti-slavery mobilization both in Senegambia and in Saint-Domingue, as discussed below and in Chapters 2 and 3. Therefore, when considering an emergent racial solidarity, as this book attempts to do, it is interesting and necessary to note the Mozambican presence as part of Saint-Domingue’s wider enslaved population (study of which is oftentimes reduced to its numerical majorities), and to be attentive to possible cultural and religious connections between enslaved Africans prior to their disembarkation in the Americas. According to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, the average Middle Passage journey for ships voyaging between France, the Southeast African–Indian Ocean littoral, and on to Saint-Domingue was over 20 days longer than trips from other African regions. These longer voyages were riskier due to the increasing likelihood of illness or insurrection, but traders nonetheless viewed trips to the Southeast African–Indian Ocean littoral to purchase captives as a profitable endeavor. Enslaver Louis Monneron agreed to sell between 150 and 300 Mozambicans in February 1781 with the exception of the sick captives who presented a financial risk to the expedition.46 Another trader contacted Monneron in 1782, seeking to order 1,000 Mozambicans in order to sell them at a later date and ameliorate his “disastrous” financial situation.47 In 1787, an inquiry was made to buy a Saint-Domingue coffee plantation in exchange for blacks from Mozambique, likely implying that the captives were of significant value since the plantation in Moka, presumably in Mauritius, was described as “a superbe operation.”48

West Central Africa

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the West Central African zone already constituted a main trading destination, secondary to the Bight of Benin, for French ships headed to Saint-Domingue (Table 1.1). Aggression from other European traders in the Western coastal regions had pushed French activity south from the Bight of Benin to West Central Africa and, in turn, the French attempted to encroach on ports controlled by other European nations. In 1705, the French were accompanied by rulers from the Dombe in an attack on neighboring Benguela, a Portuguese-controlled port near Angola, likely because they were attracted to the region for its widely purported wealth in captives and gold. Though the Portuguese maintained control over the southern Angolan ports Benguela and Luanda, the French also continued an illegal trade from southern coasts without paying Portuguese duties.49 As Saint-Domingue surpassed Cuba and Brazil as the world’s leading sugar producer, and became a prominent coffee producer around mid-century, the demand for enslaved Africans increased and the Loango Coast became the French traders’ primary source of captives.50 Ports north of the Congo River – Malemba, Loango, and Cabinda – had become primary French slave trading posts, far exceeding those of other regions. Numbers of trafficked West Central Africans doubled those from the Bight of Benin and made up well over one-third of Saint-Domingue’s Africa-born population (Table 1.2).51 These included groups from the Loango Bay and deep into the interior, such as the Mondongues, Montequets or “Tekes,” Mayombés and Mousombes.

The Loango Coast basin was an ecologically diverse region containing rivers, swamps, forests, and savannahs, and it was home to several cultural groups and languages that shared a relationship with an abundance of water and the Bantu language system, especially the KiKongo language. The various groups using this language system are collectively known as the BaKongo peoples, although their political and religious systems differed. The Loango Kingdom emerged to prominence in the sixteenth century, originally as subsidiary of the Kongo Kingdom. After establishing trading in ivory, copper, rubber, and wood with the Portuguese, the Loango Kingdom broke away and became an independent state that held power over the smaller state of Ngoyo, Cabinda, and the Kakongo Kingdom, which controlled the port of Malemba.52 In the earliest periods of contact with Europeans, trading from the Loango Bay was essentially controlled by the king, who lived directly near the coast in order to assert dominance without interference from middlemen. As trading systems developed, the Vili rose in prominence as partners to European traders who exchanged cloth, guns, and alcohol for human captives. Though the Portuguese were dominant in regions south of the river, the Vili preferred to operate with French, Dutch, and English traders who brought a wider variety of goods for lower prices.53

Vili traders captured slaves from the southern Kongo Kingdom, who were referred to as “Franc-Congos” in shipping data, and took them northward to the Loango Coast outposts.54 Political instability within the Kongo Kingdom increasingly led to Kongolese citizens being subject to enslavement, which was previously reserved for foreigners in the kingdom.55 The Kongo civil wars had their roots in the mid-seventeenth century, but peace was brought to the kingdom for several decades after two warring factions agreed to share and alternate leadership. The Kingdom of Kongo had developed contact and trade relations with Portugal in 1483, and King Afonso V was the first ruler to fully implement a European-style royal court with Christianity as its official religion. Members of the Kongolese elite were educated in Europe and built local schools where wealthy children learned Latin and Portuguese. To finance this cultural and religious revolution, Afonso and subsequent kings traded slaves and eventually resorted to waging war with neighboring states to capture slaves. Over the course of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, warfare dramatically increased the number of slaves brought to the Kongo Kingdom from foreign markets. But as the eighteenth century approached, financial demands following civil wars over succession claims to the throne and other conflicts led to expanding justifications to enslave freeborn Kongolese. Spikes in the numbers of Kongolese captives taken to Saint-Domingue overlap with royal coups of the 1760s and 1780s that overthrew Dom Pedro V and, later, his remaining allies (Table 1.2).56

Members of Pedro V’s failed succession may have been captured and sold to Saint-Domingue. Pierre “Dom Pedro” was a Kongolese runaway from Petit Goâve who declared himself free – perhaps meaning he had been freeborn – and became the originator of Haitian Vodou’s petwo dance, which was enlivened by rum, gunpowder, and a pantheon of “hot” spirits.57 Understanding West Central African perspectives on the slave trade helps explain the sacred usage of rum and gunpowder in West Central African rituals in Saint-Domingue, which I further discuss in Chapter 3. The ongoing connections and transfers of goods, knowledge, and people between Africa and the Caribbean meant that there was an historical accumulation of meaning, sacrality and power, and connection to human lives lost to the slave trade. The slave trade consumed human life, and West Central Africans who were most vulnerable to capture and sale understood the trade in terms of cannibalization and witchcraft. This spiritual and metaphorical formulation made sense given the dynamics of the trade: traders took people, and in their stead appeared material objects like cowrie shells, alcohol, and gunpowder, which were assumed to hold the essence of the disappeared person and therefore took on additional sacred meaning. Commodities like cloths and metals already had social and spiritual significance, but took on new sacred meanings in the Americas as the slave trade increased and meanings of those items – and enslaved captives – were viewed, in European worldviews, solely for their economic value (Domingues Reference Domingues da Silva2017; Green Reference Green2019: 236–238).

West Central African societies defined “witchcraft” broadly, to include actions that indicated selfishness and the abuse of power – even by royal political authorities. The greed and abuses of power associated with the slave trade, especially the increasing capture and sale of freeborn people in addition to enslaved foreigners, stimulated political and religious institutions to check the authority of the kings who ruled over the trade. Though they shared the KiKongo language, in the sixteenth century Loango was culturally and religiously distinct from Kongo. North of the Congo River, there was minimal settlement of the European colonists, who exerted less cultural, religious, and political influence than was common at the Angolan Portuguese colony. Seventeenth-century Jesuit missions resulted in several conversions, but these had negligible effect on the overall religious life at Loango, in part allowing the kingdom to maintain religious, cultural, economic, and political autonomy. The city of Mbanza Loango served as the religious and political center of the Loango Kingdom, staffed by administrative nobles with relatives of the king ruling rural provinces.58 Loango kings were held to a high moral standard of ruling with fairness and were typically seen as spiritual leaders bestowed with supernatural abilities by the bunzi priests who ruled earth and nature spirits. The kings’ sacred power needed to be protected from the outside world through public isolation and a system of operating primarily at night.59 Religious shrines doubled as judicial centers where judgement and law were determined; a series of spiritual authorities presided over these shrines and advised the king on important matters. Ngangas were priests of resurrected spirits whose broad range of responsibilities included leading ceremonies, practicing healing, and performing rituals to communicate with spiritual powers and eliminate the influence of the dead on the living. Ngangas were vital to the political realm, as their ritual power was deemed important during warfare and their sacred knowledge qualified them to be advisors to the king. Therefore, they were a constant presence in local rulers’ entourages and at public events.60

Outside of the king’s sphere of influence, a popular movement that emphasized healing and fairness grew among the Lemba society, which began in Loango and eventually reached regions southwest of the Malebo Pool.61 The Lemba believed that the slave trade was destroying society; they differed from surrounding states because of their approach to justice, the use of force, and the structure of economic resources. The Lemba specialized in trade on a decentralized, “horizontal” basis and encouraged locally-produced and traded goods. They maintained peace in the marketplace via the use of priests and conflict resolution. Any conflict or material, social, economic, and political ills were attributed to spiritual imbalances that required a spiritual response using nkisi medicinal bundles.62 Not all members of Lemba society where inherently opposed to the slave trade, however. Among Lemba adherents were Vili merchants from Loango who transported captives from the southern Kongo Kingdom to ports north of the Congo River – an exploitative economic practice that metaphorically cannibalized people and was associated with kindoki or spiritual witchcraft. The Vili’s allegiance to Lemba served to counter the negative sacred implications of their slave trading enterprise as a “spiritual means to heal the evil released by their activities.”63

The Middle Passage and Resistance to the Slave Trade

Slave Ships: Sites of Illness, Death, and Intimacy

The Middle Passage was the initial process that conflated African lives with exchangeable commodities; it might also be considered the experience that produced what would become a collective consciousness and feeling of solidarity among its survivors. The shared experience of violent extraction from one’s homeland; being branded and chained to a person who may or may not share one’s linguistic or cultural identity; the waiting period at the fortification castles; the long voyage in the belly of the slave ship; and hunger, disorientation, and death were all part of the material conditions of transport that left a lasting impression on Middle Passage survivors. Strangers bound together came to know each other in unspeakable ways, creating bonds that lasted when they disembarked at ports on the other side of the Atlantic. These relationships with “shipmates” and other cultural or linguistic familiars would form the basis of kinship networks and collective identity in the Americas through the transmission of stories, memories, or songs about the homeland experience and the Middle Passage itself. Words from a song from the Haitian Vodou tradition, “Sou Lan Me,” speak to the collective memory of the Middle Passage and the longing for liberation from the slave ship:

The traumatic experience of being trapped in the bottom of a slave ship left little help on which to depend, prompting a spiritual appeal to the spirits Agwé and Lasirèn that control the high seas and transoceanic travel, and a lament for the lives lost during the voyage.

Though scholars agree that approximately 12 million living Africans arrived in the Americas over the course of the slave trade, the mortality rates associated with each phase of the trade were undoubtedly much higher. Africans perished from warfare and raids at the moment of capture, during treks to the coast, and while bound in the fortification castles awaiting embarkation on the ships. Furthermore, the Middle Passage voyage itself incurred approximately 15–20 percent losses in human life aboard the slave ships.65 During the voyages between the African continent and Saint-Domingue in the years 1751–1800, 66,273 individuals – or approximately 11 percent of those who were forcibly embarked on slave ships – died or were killed during the course of the Middle Passage. The total loss of life associated with the transAtlantic slave trade has yet to be determined, but a growing body of information provides insight into the hellish conditions of the slave ship. Individual voyages from the African continent to American ports could be as short as two to three months; however, some lasted for up to a year (or more) when ship captains waited to fill their boats with as many enslaved people as possible from various ports of the continent while the captives themselves languished in the ship’s lower decks.

The captives were bound together by chains; they were naked and packed into the ship tightly to fit as many human bodies as possible in the bottom floor of the deck, which was dark, hot, and short of oxygen. Food consisted of a mixture of beans, millet, peas, and flour that ship hands distributed three times a day, along with a small drink of water. Exhaustion, diarrhea, vomiting, dysentery, contagions like smallpox and tuberculosis, and a wide array of other illnesses were ubiquitous among the captives, as was the overwhelming sense of despair that led many to cast themselves overboard. The population density at trading centers like Ouidah facilitated the spread of diseases such as smallpox and by the 1770s, European slavers were inoculating captives before they embarked on the ships.66 Medical practitioners who treated the enslaved were often either underqualified or lacking in resources, and they treated the captives in exploitative ways to advance their medical knowledge as well as the commercial enterprise of slaving (Mustakeem Reference Mustakeem2016: 150–155). Similar to resistance tactics used in American colonies, individual efforts to avoid slavery also included feigning illness. In 1776, a young West Central African girl seems to have effectively avoided sale to Port-au-Prince on the L’Utile slave ship by pretending to be sick.67 Women and girls were particularly vulnerable to rape by captains, sailors, and other ship hands. Ship hands held women separately from male captives and enslavers viewed them through stereotypical notions of black sexuality (ibid: 83). Though rape was common throughout the Middle Passage experience, it was rarely acknowledged in French records or reported to authorities. One case emerges from the historical record involving Second Captain Philippe Liot, who brutally “mistreated” a young woman, breaking two of her teeth and leaving her in such a state of decline that she perished shortly arriving at Saint-Domingue. Liot later inflicted his abuses on another girl, between ages 8 and 10, forcibly clasping her mouth for three days so she could not scream while he violated her. The child was sold in Saint-Domingue, but the violence she endured left her in a near “deathly state.”68

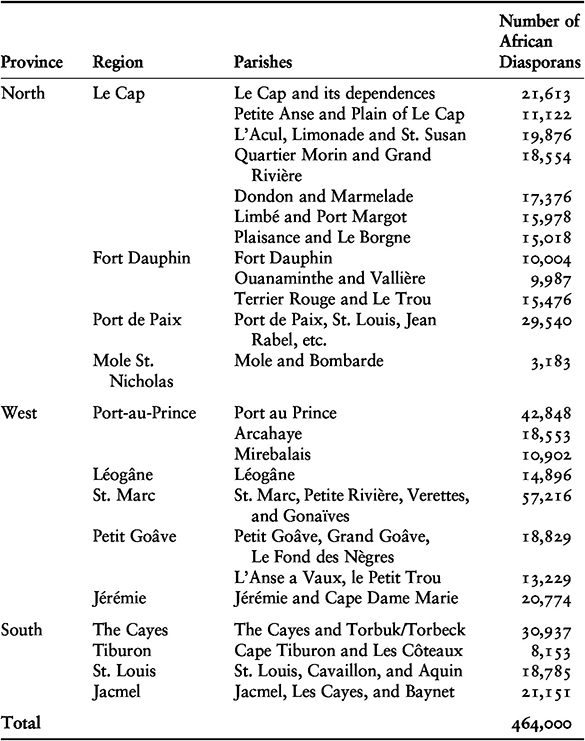

Separated from their traditional modes of survival, homelands, communities, cultures, and ancestral spirits and living kinship ties, a pressing existential question was “how captives would sustain their humanity in the uniquely inhumane spatial and temporal setting of the slave ship at sea (Smallwood Reference Smallwood2008: 125).” Africans kept track of time according to the moon cycles and formed intimate relationships with others who survived the ship voyages. They affirmed one another’s humanity on ships through small acts that went undetected by slavers, like touching, decorating hair, or expressing desire. Women captives who were pregnant when they embarked, or became pregnant through rape, delivered babies on ships with the help of midwives or anyone in proximity who could aid the process. These relationships – some sexual, some not – seem to have survived the Middle Passage and were the basis of powerful “shipmate” social ties throughout the Americas that operated as family-like or otherwise intimate networks (Mintz and Price Reference Mintz and Price1976, chapter 4; Tinsley Reference Tinsley2008; Borucki Reference Borucki2015). The ports at Cap Français and Port-au-Prince by far received more slave ships than other ports. When captive Africans who survived the journey across the Atlantic Ocean landed in the urban centers of Saint-Domingue, they confronted a new reality: foreign geographic landscapes, social arrangements, and power dynamics. They disembarked the vessels while still chained to their “shipmates” – individuals whom they may or may not have known prior to capture but who most certainly shared the bonds of surviving the Middle Passage, regional origin, cultural identity, and political affiliation, and/or religion. The “clusters” (Hall Reference Hall2005) of the newly arrived generally valued the literal and social psychological ties that bound them to their shipmates. After plantation owners purchased them at the ports, Africans gravitated to each other on respective plantations. Bight of Benin and West Central Africans could easily locate members of their ethnic, religious, or linguistic communities as they were the largest ethnic groups in the main ports in the major cities, as well as in less- utilized ports. Outside of Cap Français and Port-au-Prince, the densest proportion of Sierra Leoneans, Windward Coast Africans, and Bight of Biafrans were found at Les Cayes; Africans from the Gold Coast and Senegambians had significant numbers in Léogâne; and Saint Marc was a hub for Bight of Benin Africans, West Central Africans, and Southeast/Indian Ocean Africans (Table 1.3). Chapter 2 will further discuss the distribution of ethnic groups on Saint-Domingue’s plantations and how their spatiality may have influenced patterns of resistance. Enslaved people and maroons’ geographic location in the colony, together with their knowledge of the landscape, was an important part of their collective consciousness and this is explored in Chapter 6.

Table 1.3. Disembarkations of African regional ethnicities across Saint-Domingue ports, 1750–1800

| Arcahaye | Le Cap | Les Cayes | Fort Dauphin | Jacmel | Jérémie | Léogâne | Mole St. Nicolas | Petit Goâve | Port-au- Prince | Port-de-Paix | Saint-Marc | Port Unspecified | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senegambia | 0 | 8,425 | 730 | 416 | 131 | 0 | 2,597 | 0 | 0 | 5,608 | 0 | 1,352 | 1,009 | 20,268 |

| Sierra Leone | 204 | 7,861 | 4,053 | 0 | 143 | 0 | 244 | 0 | 0 | 5,700 | 204 | 972 | 985 | 20,366 |

| Windward Coast | 0 | 1,144 | 1,430 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 853 | 0 | 624 | 150 | 4,201 |

| Gold Coast | 0 | 7,356 | 1,182 | 0 | 0 | 107 | 2,274 | 0 | 0 | 763 | 0 | 1,062 | 1,725 | 14,469 |

| Bight of Benin | 0 | 36,810 | 4,248 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13,518 | 0 | 313 | 31,507 | 626 | 17,228 | 2,029 | 105,919 |

| Bight of Biafra | 0 | 7,134 | 7,756 | 0 | 132 | 557 | 1,024 | 0 | 168 | 7,538 | 0 | 3,024 | 562 | 27,895 |

| WC Africa | 0 | 157,084 | 19,518 | 432 | 1,616 | 382 | 28,254 | 344 | 201 | 40,065 | 1930 | 10,196 | 5,074 | 265,096 |

| SE Africa | 0 | 13,340 | 1,7000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 894 | 0 | 0 | 2,213 | 0 | 2,166 | 843 | 21,156 |

| Other | 0 | 25,496 | 3,893 | 0 | 506 | 270 | 3,295 | 0 | 0 | 15,400 | 382 | 5,964 | 5,626 | 60,832 |

| Total | 204 | 264,650 | 44,510 | 848 | 2,528 | 1,316 | 51,740 | 344 | 682 | 109,647 | 3,142 | 42,588 | 18,003 | 540,202 |

African Marronnage, Rebellion, and Revolution

The stark economic inequality between African aristocracies, merchant classes, and the masses contributed to a growing African oppositional consciousness and widespread revolt against the slave trade. Resistance to enslavement in the Americas did not spontaneously appear once captives disembarked from slave ships and reached plantations – it was predated by, and in some cases may be considered as an extension of, African wars and resistance to local forms of slavery and the onslaught of European trading. When centering Africa and Africans, marronnage, revolts, revolutions, and indeed the progressive human ideals that defined the Enlightenment era and the Age of Revolutions might be equally informed by African political sensibilities. Sylviane Diouf’s Fighting the Slave Trade: West African Warfare Strategies (Reference Soumonni and Diouf2003) offers insights into the little-known aspects of the defensive and offensive strategies Africans took to contest the slave trade, and African conceptions and practices of warfare. This chapter has highlighted the origins of what would become a politicized, oppositional consciousness in Saint-Domingue through a brief excavation of the African background and its role in shaping enslaved people’s approaches to resistance. The shifting landscape of political ideology tilted African masses against forms of rule associated with the greed and violence of the slave trade, and the pervasiveness of war meant that some were armed with militaristic tools that, though unsuccessful on the continent, would prove useful in the Americas (Thornton Reference Thompson1991, Reference Thompson1993b; Barcia Reference Barcia2014).

Given the sheer volume of the slave trade and its duration, one wonders how social structures and institutions responded to its imbalanced nature and its destructive effects on local communities. Scholars agree that the collapse of several major states and empires prior to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries meant that the vast majority of Atlantic Africa was composed of a multitude of fragmented states that could not mount a real defense against foreign powers. Europe’s demand for gold, kola nuts, and other African products was not detrimental to the decentralized states, but as market demands called for human beings, violence escalated to levels that these smaller states were not fully equipped to handle. This is not to mention the commercial and politico-military advantage that European nations had over Africans, given a longer period of consolidation and world trade, which put African leaders in a reactionary position in relation to the changing needs of Western European economies. Class divisions also contributed to social cleavages, which Europeans were able to take advantage of when imposing the slave trade. Resistance to the trade from local African rulers was uncommon, since they and others of the merchant elite classes benefited financially and would not have been affected by the trade in any tangible way.69

Two women, Queen Njinga of Ndongo (Luanda) and Dona Beatriz of Kongo, led mid-seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century West Central African resistance movements that were notable exceptions to the notion that African rulers were complicit or failed to utilize their economic or military resources to resist the transAtlantic slave trade. After decades of peaceful trade relations between the Portuguese and the Kongo Kingdom, the Portuguese set out to conquer the kingdom of Angola, or Ndongo, in 1575. This campaign leveled a heavy blow to the kingdom’s power in the region, which was based on a tributary system of surrounding polities paying dues. Though Ndongo withstood Portugal’s incursions for a short while, the successive deaths of Njinga’s father and brother led to a deepening of the slave trade and created a vacuum of power that she was fully prepared to fill in 1624. Njinga used a wide-ranging political repertoire, including diplomatic ploys, guerrilla warfare, and ritual symbolism, to position herself as a formidable military leader, pause the slave trade, and establish peace with the Portuguese in the mid-seventeenth century.70

Under the influence of Saint Anthony, Dona Beatriz led an early eighteenth-century spiritual and political movement to unify the Kongo Kingdom. To introduce broad reformations, she advocated for the exaltation of Saint Anthony and opposed local priests by asserting that Jesus and Mary were Kongolese people born in São Salvador. Dona Beatriz’s movement was heavily supported by women, as she fashioned herself as a healer of fertility issues and attempted to create an order of nuns. Her message propagated widespread prosperity and the coming of an age of miracles. This was popular among the peasantry, who were eager for an end to the constant warfare that was feeding the slave trade. The Antonian movement’s increasing relevance and political allegiances with opponents of King Pedro, and its calls for peace and an end to greed and abuses of power – which were considered to be manifestations of kindoki spiritual witchcraft – presented it as a target to the prevailing monarchy, which resulted in Dona Beatriz’s execution.71 Yet the movement did seem to have a measurable, though temporary, impact on the slave trade. The years of the Antonian movement correspond with the lowest levels of slave trading West Central Africa had seen since the 1650s and 1660s – a period that overlaps with peace treaties between Queen Njinga and the Portuguese. The years after Dona Beatriz’s death saw a gradual increase in the slave trade from West Central Africa. By the late eighteenth century this would become the most frequently exploited region, exceeding the Bight of Benin.72

Religious consolidation in West Central Africa, as well as Senegambia, helped to mount the solidarity needed to mobilize diverse groups into a united front that could oppose European armies who represented merchants involved in the slave trade. There was a long tradition of Senegambian resistance to the slave trade in the form of religious discontent among Muslims, who held Qu’ranic beliefs that they could not be enslaved. Islam had been present in West Africa from as early as the ninth century but was largely associated with long-standing merchant networks that bought and sold human captives, kola nuts, European imports, commercial activity, and political allegiances. Though not every Senegambian was Muslim, most were in some way familiar with or proximate to Islam, and as the religion spread so did upheavals on the African continent that had direct a influence on the slave trade. In the early seventeenth century, a more militant form of Islam emerged to counter the Atlantic slave trade and the growing instability that it engendered. Nasir Al Din led a religious movement to control local trade markets and to introduce a more righteous Islamic practice. With the aid of local factions and members of the marabout class of Islamic clerics, Al Din’s short-lived movement deposed several kingdoms and replaced them with theocracies. Though Al Din’s movement failed when Saint-Louis chose to continue the Atlantic trade and to support autocratic regimes, many marabouts migrated south to Futa Jallon, where they would continue to seek autonomy for Muslims in the early eighteenth century.73

The shared heritage of Islam, and the intensification of the trade at Senegambia, Sierra Leone, and the Windward Coast, may have contributed to the rise of revolts from those areas. Rising prices for captives led to a breakdown of local Senegambian conventions that were intended to protect free people, domestic slaves, and Muslims from the slave trade (Richardson Reference Richardson and Diouf2003). Fighting between the Muslim Fulbe and the Mande-speaking Jallonke resulted in jihad that as early as the 1720s, and reaching its height in the 1760s–1780s, violently pushed Sierra Leoneans into the slave trade in increasing numbers.74 By 1776, growing intolerance of the enslavement of Muslims resulted in a revolution against the slave trading nobility at Futa Tooro. A popular uprising against the trade developed, with Muslim clerics like Abdul-Qadir Kan at the helm, as the slave trade increased in volume at the end of the eighteenth century. The revolution nearly ended slavery and the slave trade from Futa Tooro by prohibiting French traders from traveling up the Senegal River to procure Arabic gum and captives. The abolition of the slave trade at Senegambia was widely known and even represented a model for white abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, who lauded Kan’s actions. Despite the ban of slave trading activity at Futa Tooro, the French continued to work with the rebels’ enemies to procure slaves and other resources from Gorée and Saint Louis, thus undermining the revolution.75

Resistance among potential captives was a regular occurrence, since – besides those who were already enslaved according to local custom for being a criminal or in debt – most individuals taken to the Americas were victims of some other financial crisis, or were either kidnapped or prisoners of war. These were free people who were losing their original liberty, personal dignity, familial and community networks, and connections to their homeland and ancestral deities due to the trade. Africans, especially those who lived in the interior lands, did not always have a clear idea of Europeans’ intentions or the location of those who had disappeared. Despite the opaqueness of the nature of the slave trade, there was a general sense that malevolent forces were at work and a knowledge that lives were in imminent danger. Individuals, families, and entire communities took precautions to protect themselves.

Flight from communities that were vulnerable to raiding seems to have been a common form of resistance for those affected by French slaving. What is today the Ganvié lacustrine village in the Republic of Benin is an historical example of a community’s flight to the waters to avoid the violent encroaching power of the Dahomey Kingdom’s slaving of smaller polities and decentralized peoples. The Tofinu is a homogeneous ethnic group closely related to the Aja groups that developed from generations of migrants who, beginning in the late seventeenth century, settled along Lake Nokoué and surrounding swamplands within the coastal lagoon system. According to oral tradition, Ganvié means “safe at last,” which references the earliest settlers’ sense of refuge from the onslaught of slave trading that increased when Dahomey conquered Allada in 1724, Ouidah in 1727, and Jankin in 1732. Ganvié was a maroon community that fashioned its survival in ways that emerged alongside similar communities in the Americas. Upon arrival to Ganvié, newcomers who may have been local slaves were freed and protected from the pervasiveness of slaving. To protect the community, members utilized canoeing skills that were lacking among Dahomean armies, mounted expeditions to find wives, and used a wide array of weaponry, including javelins, sledgehammers, swords, and locally made and imported guns.76

West Central Africans also fortified themselves; as early as the sixteenth century, enslaved people at the plantation-based island São Tomé escaped into the mountains and revolted in 1595, convincing the Portuguese to move their sugar production operations to Brazil.77 In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, there were known quilombo maroon communities such as Ndembo, just south of Loango near Luanda, who fled Portuguese slave trading at Benguela. Quilombos originally emerged in the seventeenth century as military structures associated with Imbangala (also referred to as the “Jaga”) traveling warrior forces, some of whom sold captives to the Portuguese while others waged war against Ndongo and Matamba in revolt against the political and economic pressures that arose alongside the slave trade. The quilombo collectives allowed the Imbangala to “unite people from different lineages speaking different languages,” a characteristic that would figure prominently in the Americas when quilombos were essentially exported to Brazil, most notably at Palmares, due to the growing slave trade.78 By the early eighteenth century, quilombos on the West Central African coasts, especially at Luanda just south of the Loango Bay, were largely associated with communities of runaways who had evaded capture by slave traders. Several quilombos grew in part due to support from local African leaders and free individuals who were complicit in protecting the runaways, as well as from quilombo raids on Luanda residents who owned enslaved people. Accounts from the early eighteenth century record a series of attacks by quilombo members – who originated from Benguela – assaulting and robbing Luanda residents, taking goods, supplies, and enslaved captives. At Luanda, would-be slaves and enslaved domestic workers feared the slave trade; they used their kin networks to escape, taking windows of opportunity when their owners were out of sight. A group of 130 slaves escaped in 1782 when their owner made a trip in search of gold mines.79 Despite regular attacks on maroons by Luanda officials, and attempts to offer amnesty to those who returned, these communities increased in number into the late eighteenth century. Luanda’s maroons were incorporated into local rulers’ armies and were used to attack members of the merchant class, as occurred in 1784 when traders reported “significant financial damage due to the large number of escaping Africans making their way to Ndembo.”80 These patterns of flight, armed resistance, and re-appropriation of forms of capital might be considered the antecedents to marronnage in the Americas.