Let us suppose that the rest of this book is to be believed. The rule of law is about equality, in the dual sense that its moral value is derived from its contribution to the equal standing of those subject to the law, and it will be maintainable for the long term only in states that actually have legal systems that treat their citizens as equals. This contrasts sharply with the conventional views of the rule of law according to which it is primarily about liberty (philosophers) or economic development (social scientists), and will be maintainable through Western-style constitutional and judicial institutions. The egalitarian theory of the rule of law represents an opportunity to open a new conversation about how policy makers and development specialists should understand the rule of law.

That conversation, however, should be focused on empirical potential, not policy prescription. I am not an experienced development practitioner, nor do I have the local expertise necessary to propose concrete rule of law development initiatives in actual states. What I, with the aid of the egalitarian theory of the rule of law, can offer, however, is (a) a set of potential policy approaches that may be adapted to real-world contexts, but that should be implemented on a large scale only with the aid of local expertise and after being empirically validated – as well as a new kind of argument in support of those who have already advanced similar approaches, and (b) an approach to measuring the rule of law that can help in the task of empirical validation by giving us some way to test how policy interventions work on a state-by-state level, as well as test the theoretical claims often made about the side benefits of the rule of law, such as its usefulness for economic development.

I Rule of law development

The previous chapters suggest three general principles for rule of law promotion, which may be tested and empirically evaluated. I will call them persuasive commitment-building, generality development, and radical localism. The key idea underlying each is from the previous chapter: rule of law promotion will be more likely to succeed if the people in the communities in which policy makers are attempting to promote it can come to endorse and be committed to preserving their state’s legal systems. This, in turn, suggests that those systems must serve their interests, must be implemented in a way compatible with their local ideals and cultures, and must be advocated for with respect for the role of the actual citizens of the communities in which the law is to be promoted.

While my aims in this section are modest, they still represent a radical contrast to the “Washington consensus” school of rule of law promotion, which aims to promote the rule of law in order to promote so-called market reforms – that is, to make the world safe for capitalism, where the capital owners often are from the promoting countries rather than from the countries in which the rule of law is being promoted. Something of the priorities of this school can be seen in the following quintessential development community passage, from a market-oriented review essay on the development of the rule of law in Latin America:

While the swift and decisive decision-making needed to implement first-generation market reforms often requires a pliant judiciary, second-generation economic reforms aimed at anchoring the institutional foundations of the market economy require precisely the opposite. Market-oriented economic reforms are not sustainable without restoring and strengthening the credibility of the rule of law. As the reliability of the legal and judicial process increases, so does the credibility of the public policymaking process. More fundamentally, government by executive decree, while an asset in the initial phase of economic reform, progressively becomes a liability in the second phase of reform.1

That author evidently views the rule of law in purely instrumental terms, not for its inherent moral value, or even for its direct effects on the well-being of the people in whose communities it is to be promoted. To the contrary, “government by executive decree” is to be supported in the first stage of “economic reforms.” The author never says what this first stage is, but the undersigned cannot help but fear that he’s talking about Pinochet-style market authoritarianism: precisely the opposite of the rule of law. I submit that this attitude is bound to lead to failure, as those in the communities in question have zero reason to support a legal system that is not viewed even by its promoters as independently valuable or even worth keeping if it turns out to impede their preferred form of economic organization. In addition, this method of promoting the rule of law fails to attend to the underlying normative value of the ideal; unsurprisingly, without a clear normative concept of the rule of law in the heads of its promoters, they find themselves simply attempting to transpose bits and pieces of their own institutions into other countries – a practice that Martin Krygier has aptly diagnosed as “abuse of the rule of law.”2

As the wave of global activism beginning in the globalization protests of the late 1990s and continuing with the recent Occupy movement has shown, many do not believe that market reforms and legal institutions meant to support capitalism are in the interests of the masses in the countries in which they are promoted. The truth of that question is open to debate, and many economists and policy makers would argue that they genuinely are in the long-term interests of all in the communities in question, but attempting to promote the rule of law on the basis of such controversial economic as well as normative claims is a recipe for failure, and represents a lack of respect for the legitimate views and concerns of those in the societies with whose legal institutions the development community is involved. Little wonder, then, that rule of law promotion has had decidedly mixed international results: to me it seems most likely that this is a consequence, at least in part, of inadequately inclusive processes as well as outcomes, ones that, in the terms of this book, fail to be general.

In discussing the rule of law’s potential to serve the cause of justice, E. P. Thompson also inadvertently explained why instrumentalist rule of law promotion in the interests of global capital is a doomed enterprise:

[P]eople are not as stupid as some structuralist philosophers suppose them to be. They will not be mystified by the first man who puts on a wig. … Most men have a strong sense of justice, at least with regard to their own interests. If the law is evidently partial and unjust, then it will mask nothing, legitimate nothing, contribute nothing to any class’s hegemony. The essential precondition for the effectiveness of law, in its function as ideology, is that it shall display an independence from gross manipulation and shall seem to be just. It cannot seem to be so without upholding its own logic and criteria of equity; indeed, on occasion, by actually being just.3

This argument seems quite right to me: even from the standpoint of the self-interested desires of the Western economic powers, law that is blatantly aimed at promoting their economic interests will not be effective, as Thompson puts it, “in its function as ideology.” Accordingly, it will not be effective at promoting those interests. Evidently unjust law, or law imported by outsiders that fails to pay due regard to the interests of the actual stakeholders in a society, cannot expect to win the support of those stakeholders. It is far more likely to encounter their active resistance.

Sadly, some elements of the rule of law development industry are in dire need of reform. The worst example I have ever discovered is from one of the international experts who was brought in to help build the rule of law in Afghanistan, but whose published writings display an open contempt for the country, its traditions, and its people. A professor at the University of Copenhagen, he, according to his online faculty profile,4 “set up the ongoing legal training programmes of the Max Planck Institute in Afghanistan.” He also has written a book chapter, in which he said the following about the Afghan resistance to the Soviet invasion: “Self-serving descriptions by its protagonists notwithstanding, the Afghan conflict was only marginally a national defence against a foreign aggressor. Primarily, it was a civil war fought between those who favoured accelerated modernisation and those who resisted this change with reference to an atavistic understanding of religion.”5 Speaking of the “atavistic” religion of the Afghan people: “However aggressive, intolerant, and backward widely prevailing notions of Islam in this country have been, it is the lack of effective governance, not religious parochialism, that brings about chaos and poverty.”6 On the very same page, he tellingly asserts that “the general quality of legal expertise going into the [constitutional drafting] process must be described as poor” because (the causal implication is unstated but unavoidable) “[o]utside technical assistance was available in principle but was utilised only very haphazardly and incoherently; by and large outside legal expertise was seen at best as an irritant to inter-factual horse-trading and at worst an attempt at cultural domination.”7 One might dare to think that the writer, qua member of the “outside legal expertise,” was indeed engaged in an attempt at cultural domination over the “backward” and “atavistic” version of Islam endorsed in the community. Nor does the state itself escape his scorn. In his two-sentence summary of the entire history of Afghan statehood he describes it as “depend[ing] on foreign largesse” and “extract[ing] significant rents” from the world powers.8

Of course, the sins of a few cannot be visited on the rule of law development enterprise as a whole. However, it is hard not to suspect that the Washington consensus approach to rule of law development might encourage this kind of attitude. And there is something about this lack of respect for existing traditions that seems to be more widespread than the extreme example I have just quoted. Such externally imposed rule of law development patterns have been described by Ugo Mattei as “imperial.”9 As Mattei points out, the US/Western legal system denies that legal systems unlike its own actually count as legal systems – what Mattei calls “de-legalization.”10

Accordingly, I offer this book in part as a theoretical grounding for those who endorse alternative approaches to rule of law development, particularly what might be called the “bottom-up” rule of law development movement (associated, inter alia, with Carothers, Kleinfeld, and others associated with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace), and offer the following as a catalog of ways in which the theoretical material of this book may connect with the kinds of efforts they support.11

A Persuasive commitment-building

One of the themes of this book is that the rule of law in the first instance requires a general commitment to the law. That commitment is the precondition for, not a consequence of, functional formal institutions like courts. Thus, the egalitarian account of the rule of law suggests that the task of rule of law development is partially to persuade people that it is in their interests to act collectively to enforce the rule of law.

Of course, to persuade citizens to support a rule of law that is not, actually, in their interests is to subject them to oppression; to dishonestly persuade citizens that they can safely act in concert to defend the law is not only to subject them to potentially brutal retaliation, but also to undermine the extent to which they will believe in the viability of collective enforcement of the law later. For that reason, persuasion is necessarily subordinate to substantive reforms to make the legal system worth supporting.

B Generality development

As Chapter 8 argued, members of a political community will have reason to support the rule of law only if the law is compatible with their interests, and more so if it is publicly fair – that is, if the law is general. Accordingly, the egalitarian theory of the rule of law suggests that rule of law development efforts focus on making the law general, by, inter alia,

(a) Controlling violence under color of the state, particularly against the most vulnerable, and ensuring that all have access to legal remedies against violence.

(b) Eliminating legalized discrimination by gender, race, religion, class, caste, sexual orientation, and other group identities.

(c) Actively promoting social equality through the law by implementing legal protections against private discrimination.

(d) Actively promoting political equality by giving members of all groups access to the legislative process, thereby allowing all groups to see that their interests are taken into account in the making of the laws that they’re being asked to support.

(e) Dispersing access to nonlegislative sources of political power, such as property, the press, the professions, civil society, and military participation.

(f) Implementing a program of economic egalitarianism and a social safety net, to increase the pool of stakeholders in the stability of society in general.

C Radical localism

Even though no particular institutions are necessary to establish the rule of law in a state, the account in Chapters 6 and 8 suggests that some institutions will be helpful in bringing it about, particularly those institutions that permit citizens – having been convinced of the value of a secure legal system to protect their interests, and in an environment where the legal system actually does treat them as equals – to credibly signal their commitment to that system. However, what those institutions are will vary from society to society. Many societies will have preexisting institutional resources that can be adapted to this signaling function, rather than attempting to transpose institutions wholesale from the North Atlantic liberal democracies.12

For example, many communities in India feature local councils, the panchayats.13 A rule of law development in such a community could feature efforts to expand access to the panchayat, and encourage the government to recognize decisions of a panchayat as binding on state officials. To the extent a community’s panchayat is already generally accepted as a legitimate source of rulings, this may be more effective at producing widespread participation in legal adjudication and enforcement – and hence widespread signaling of legal commitment – than reforms to courts.14

Religious authorities may also be recruited in communities with a tradition of religious involvement in civil dispute resolution.15 So may civil society organizations, the press, and other unofficial methods of communicating public sentiment about the law. We might imagine a state, for example, in which the government is held to comply with law not through courts, but through local and informal methods of imposing social sanctions on disobedient officials – shunning, perhaps, or gossip, or the refusal to trade with misbehaving officials. To the extent that sanctions deployed by such institutions can be seen to represent the will of a critical mass of the community, and to the extent they can be brought to use those sanctions against officials who disobey the law, these – the theory of Chapters 6 and 8 suggests – can provide institutional support for the rule of law.16

Such institutions may do better than Western-style elite judicial institutions at supporting the rule of law in communities where there is no widespread common knowledge of public endorsement of the state and legal system, on the basis of the model given in Chapter 6. Participatory mass, or representative, rather than elite, adjudications can be used not only to rule on the question of whether officials obeyed the law, but also to cheaply signal commitment to the law, and to the particular outcome of a case. Imagine a small town and a police beating, and suppose that the victim of the beating can turn for justice either to an out-of-touch and widely distrusted court operated by the central government (and built by the United States on the model of its own judicial system) or to a local religious leader, where the latter will call upon a community forum to judge the dispute and settle upon a remedy. The latter is, all else being equal, more likely to be effective, not only at finding a remedy for the misconduct, but also in deterring this misconduct in the first place, for police officers in a community with active mass adjudication will know that their fellows are committed to carrying out the result of decisions made in common, and will know that there are consequences to abuses that turn the community against them.

Moreover, such institutions are likely to draw additional public support not only from their direct recruitment of public participation but from the fact that the norms upon which they draw to constrain the use of power – be they customary law, statute law, religious norms, or the like – necessarily must be compatible with that popular participation. Accordingly, they are likely to enforce norms that are widely accepted within the community (or at a minimum accepted by the powerful, which is better than accepted by nobody).17

Moreover, Katharina Pistor has pointed out that legal institutions that are locally derived are the products of learning and institutional evolution over time, and are more likely to be adapted to local conditions than imports, however certified by external expertise.18 Her argument applies not just to substantive law, but also to procedural law, such as the details of the legal mechanisms at work in a community. If a community has, for example, eschewed centralized Western-style courts for hundreds of years, it behooves external rule of law promoters to consider the possibility that perhaps the absence of such tools is embedded in a coevolved local ecosystem in which cultural and moral norms, dominant social (and religious, etc.) beliefs, adjudicative forums, and substantive legal rules are mutually interdependent, such that transplanting external institutions will be ineffective.19

Of course, not all evolved systems are maximally beneficial to the organism, whether that organism is a person or a state. Evolution finds local optima, not global optima; an institution that is too costly to abandon might nonetheless be harmful overall for the society in which it is embedded, as a trait to a person (witness the human appendix and the American electoral college). But observing that a given legal institution (“customary,” “informal,” or otherwise) has survived in its social context gives us some reason to believe that there may be hidden costs to abandoning it and supplanting it with institutions that have succeeded in other states.

“Local” in this subsection has been used to contrast with “foreign,” to refer to the institutions that are native to the country and culture in which the rule of law is being promoted, rather than to the promoter countries and cultures; in that first sense, “local” is a rough synonym for “traditional.” However, “local” also carries the meaning of “decentralized,” and there, too, the theory of this book can connect with concrete policy potential for rule of law promoters.

There is empirical evidence suggesting that radically local development can successfully serve a violence-reducing dispute-resolution function. Blattman, Hartman, and Blair recently implemented an experiment in which community members in Liberia were trained in problem solving and alternative dispute resolution within their local cultural contexts (including the effective use of traditional forms of dispute resolution, such as “adjudication by community leaders”).20 The result was a persistent decline in violent dispute resolution among treated groups, even though the central state had largely failed to provide them with legal resources. Importantly, this produced positive change even though, before the experimental treatment, local residents had reported a multiplicity of conflicting central (“formal”) as well as traditional (“informal”) authorities, leading to “forum-shopping” and clashing unenforced judgments.21 Training in the effective use of traditional forums seems to have ameliorated the downside of local and pluralistic adjudication. Moreover, some of the positive effect seems to have resulted from making adjudication even more decentralized than it already was: subjects reported resolving disputes within the community, rather than taking them to a mishmash of central and traditional authorities (who were all corrupt, albeit in different ways).22

Better yet, subjects reported that these methods led to dispute resolutions that were actually in the interests of the parties, and thus “self-enforcing,” and led “traditionally low-powered groups” to demand improvements in their social position; that is, it tapped into the rule of law’s pressure toward generality (Chapter 8).23 This was only one experiment, and the experimenters did see some negative effects (particularly an increase in unjust extralegal punishment, such as witch-hunting24), but, on the whole, it is a promising result.

Additional promising evidence on radical localism comes from Afghanistan.25 Kleinfeld and Bader report on a program that identified those likely to be recruited as leaders by insurgent groups and jumped the gun on them, recruiting the nascent leaders instead for community infrastructure-building projects based on local materials and knowledge, such as soil conservation.26 This effort successfully kept those leaders out of insurgent groups, and their communities began to see them “as leaders who could be counted on for advice and wisdom” and “agents of reconciliation.”27

Strikingly, over time the leaders recruited for things like soil conservation actually found themselves mediating civil disputes over, for example, land rights, and, as Kleinfeld and Bader point out, this “prevented insurgents from exploiting such community conflicts by providing shadow governance services themselves.”28 Even when the outside development agencies were only trying to create leaders to work on physical infrastructure projects, they ended up accidentally creating leaders in local justice, which successfully competed with the Taliban and other violent groups. The results of that project offer substantial reason to hope that more intentional local justice projects have a strong chance of succeeding.

The Special Inspector General for Afghan Reconstruction reports that such “informal” justice programs as exist have succeeded in both bringing people to justice and advancing women’s rights:29 they got no fewer than 5,192 elders to agree to stop using baad – a traditional practice in which women are traded as compensation in civil disputes30 – as a dispute-resolution method, and found that citizens who turned to elders who had participated in the program “showed improved perceptions of procedural fairness and overall justice.”31

1 Locally driven project design

Just as one way to bring it about that the law is substantively general is to enact it pursuant to a (deliberative) democratic process that generates enactments based on reasons that citizens understand to apply to them, one way to bring it about that the legal system is procedurally legitimate, such that it is likely to win the commitment of the public, is to involve the public in its design. Rule of law development projects in which the leaders are drawn from the local population, rather than from international organizations or distant central governments, may benefit from greater knowledge of local conditions, a greater ability to recruit widespread community support, and superior access to preexisting local institutions.32

This is not to deny a role for external expertise: economists, political scientists, lawyers, sociologists, and others have valuable knowledge that can be put to work in implementing or reforming rule of law institutions even in unfamiliar countries. However, there are more and less locally driven ways to deploy this expertise.

In the engineering and product design fields, a minor revolution has taken place in recent years surrounding a concept known as “design thinking,” which is more user-oriented than traditional methods. For example, it begins with a process of “needfinding,” consisting essentially of open-ended conversations with potential users where the designer aims to produce a product that actually meets needs, rather than produce a product that looks exciting to the designer and then find the needs that it meets after the fact. Similar close-in empathetic interactions with the user are carried out throughout the development process.33

Lately, design thinking has gone beyond the product world to the field of social design, applying empathetic and interactive processes to social organization and institutions.34 Design-thinking principles might also be applicable in the international design of legal systems (i.e., the use of international expertise primarily to support the express rather than implicit legal needs of those in the local community).

“Design,” here, includes both procedural and substantive elements. Procedurally, it can mean building the institutions that the local citizens say they need, rather than those that external experts think they need. Substantively, it can mean focusing on problems that are a priority to the local people rather than to external stakeholders such as international commercial interests. If the people say they need immediate protection from police violence, for example, building courts to assist them in resolving private land disputes, while worthy, may not be as effective at winning their endorsement or participation as addressing police misconduct would be.35

II Studying the rule of law: new empirical directions

Accurate cross-national measures of the rule of law would be useful to evaluate policy interventions to promote it as well as claims about the benefits associated with it. Unfortunately, no existing measure of the rule of law is adequate. The problems with existing rule of law measures are widely recognized. Preexisting rule of law measures have been criticized for, among other things, paying little or no attention to conceptualization;36 inappropriately including nonlegal factors, such as crime rates;37 adopting proxy variables that are riddled with measurement error, are miscoded, and make unwarranted assumptions about the relationship between the proxy and the rule of law;38 being unduly focused on legal rules relevant to business and property rights;39 including copious redundancies as well as irrelevant ideas;40 focusing (in some cases) on meaningless de jure claims written into a country’s laws without regard for whether they are enforced;41 and being unclear or inconsistent about how different alleged dimensions of the rule of law are to be aggregated and weighted.42

Unfortunately, these criticisms are, on the whole, warranted. A brief review of some of the most prominent or recent measures will shed some more light on the problem.43 By far the best of the existing rule of law measures is that given by the World Justice Project (WJP), on whose data set my own measure is based. The WJP’s rule of law index is based on carefully designed original survey instruments, and surveys a large number of both experts and members of the general population across the world. It has also been subject to careful and independent statistical scrutiny.44 However, the WJP’s interpretation of its data is marred by a lack of conceptual ambition: it divides its understanding of the rule of law into eight factors – “limited government powers,” “absence of corruption,” “order and security,” “fundamental rights,” “open government,” “regulatory enforcement,” “civil justice,” and “criminal justice” – and does not attempt to unify these factors into a single scale. As discussed in the next section, this raises significant interpretive problems in, for example, figuring out how to classify a state that scores highly on one factor but poorly on another. Moreover, the WJP’s factors include a number of irrelevancies: for example, its survey measures how often bribes have to be paid to obtain medical treatment, the effectiveness of national environmental enforcement, and the effectiveness of local arbitration, which may shed some light on the effectiveness of a state’s legal system in general, but do not shed any particular light on the rule of law as such.

Other measures are significantly worse. The World Bank produces what it calls “Worldwide Governance Indicators,” which simply concatenate a variety of other organizations’ measures, and are heavily biased toward both the views of business interests and data reflecting those interests, such as the “business cost of crime and violence” and “intellectual property rights protection.”45 Moreover, the World Bank indicators do not permit cross-country comparison, as the variable coverage is different across countries and regions.46 While the Bank’s researchers have attempted to answer these criticisms, the chief answer they offer is that their measures are highly correlated – commercial evaluators are highly correlated with noncommercial evaluators, and the various kinds of measures for a different concept, such as corruption, are highly correlated with each other in the countries in which they do overlap.47 However, while that reduces the impact of these criticisms, it does not eliminate them completely. Consider the example the Bank’s researchers offer: suppose country A has only a score on a judicial corruption scale, while country B has only a score on an administrative corruption scale.48 It may be that those two sorts of corruption are sufficiently correlated that we can sensibly suppose that both are measuring a latent variable of corruption in general, as the Bank’s researchers claim. But we evaluate our measurement tools with reference to the available alternatives, and those alternatives include measures consciously aimed at tracking the same kind of corruption, such as the WJP’s, which necessarily feature less room for the error introduced by using different measures to capture a latent variable idea of corruption. And this is before we even get to generalizing from “corruption” to the rule of law – a point on which this example sheds particular light, since, as a conceptual matter, judicial corruption is far more relevant for the rule of law than administrative corruption, since administrative corruption might include corruption in domains that do not relate to the control of state coercive power (such as in the provision of public services), while judicial corruption raises serious doubts about the ability of the courts to control state violence.49

The design of the proposed United Nations Rule of Law Indicators instrument is somewhat better than the World Bank’s. However, it also includes a number of irrelevant items, such as access to health care in prison, effectiveness of the police at controlling crime, “budgetary transparency,” and the like.50 More signficantly, it doesn’t come attached to any data: the UN merely provides a standardized instrument that it advises stakeholders to use to measure the rule of law in their states. Standardized is a step in the right direction: at least this can avoid the methodological difficulties inherent in the World Bank’s approach, and should this instrument be used on a worldwide scale, it could produce data comparable to, or even better than, the WJP’s. However, the instrument would also be very difficult and expensive to use, as it suggests drawing not only from survey data but also from field research and review of national documents.

Finally, the most interesting recent entrants in the rule of law measurement races are Nardulli, Peyton, and Bajjalieh, who use a novel method based on interpreting a cross-national data set of the content of constitutions.51 Their measure is characterized by a careful attention to conceptualization issues, an attempt to base the measurement on “objective” data, and a data set that spans across time as well as across many countries. It also has the distinct advantage of treating the rule of law as a unidimensional concept rather than a noncomparable set of factors. However, the Nardulli et al. measurement suffers from one fatal flaw: one of its variables, the “objective” one, is purely de jure, consisting entirely of claims written into nations’ constitutions, and need bear no relationship to the actual constraints on official coercive power in a state. The other measure is simply the extent to which a nation has a robust field of legal periodicals (“legal infrastructure”). To see the problems with this measure, we need only note that the 1936 Soviet constitution provided for judicial independence and the supremacy of law, equal rights, free speech, free press, and a whole host of other liberal-democratic ideals that Josef Stalin obviously had no intention of fulfilling.52 Moreover, as far as I can tell from the literature available in this country, the Soviets had at least a fair amount of legal scholarship.53 The Soviet Union was quite possibly the most efficient system for wielding arbitrary power against a population that the world has heretofore seen, but the Nardulli, Peyton, and Bajjalieh measure would categorize it as having achieved a high degree of the rule of law.

Accordingly, I have created a novel measure of the rule of law. This is only a proof of concept, for I do not have access to data sufficient to make a measure that can be repeated over multiple years, or over as large a set of countries as may be desired. Instead, thanks to the kindness of the World Justice Project, I have received one year of their data, and have extracted a unidimensional measure from that data. As will be seen, this measure behaves much like we would expect a rule of law measure to behave, and accordingly reflects a credible technique for proxying an observation of the property in real-world states. Researchers with access to more data may use similar methods to achieve wider-scale and multiyear measures that may be of practical use in social science as well as in program management.

A The new measure: methods

The alternative rule of law measure here is based on its theoretical conceptualization as a undimensional property of states, suitable to be approximated on a unidimensional scale.

1 Structure and scaling

As we’ve seen, the conventional approach to measuring the rule of law, and the one taken by the best of the existing measures, is to conceive of it as a multidimensional construct – an odd composite idea comprising a series of factors tracking, loosely, a mishmash of ideas that have more or less traditionally been associated with the rule of law. This method carries with it a number of problems, however. First, on an empirical level, it’s not clear how to interpret the notion of a state having the rule of law to a greater or lesser extent, if the rule of law is a multidimensional concept. Suppose a state has a really good informal justice system, but its formal justice system is corrupt. Does that state count as having more or less of the rule of law than a state with no institutions of informal justice, but with a pristine and uncorrupted legal system? In the statistical literature, this is the problem of weighting factors.54 It is widely recognized as a critical problem in the existing attempts to measure the rule of law, one that has led some scholars to propose abandoning the attempt to measure the rule of law as a whole altogether and just measure each factor individually.55 By contrast, a unidimensional concept imagines that each measurement item (such as a survey question) is an observation of the same thing. The only reason one needs to include multiple items in a measurement of a unidimensional latent variable is that each item measures the variable with some error.

Second, on a practical level, the point of measuring a multidimensional construct is not at all clear. We presumably attempt to measure the rule of law because we want to know where and how it obtains, and its effect on the world. If we wanted to measure “open government” and “effective criminal justice,” we could measure those things on their own; if we wanted to measure the effects of having both of those things together, or any linear combination of the various factors in these multidimensional constructs, then we can use interaction terms in ordinary multivariate regressions to do so. We don’t add any insight or explanatory traction to the world by imagining that there’s some odd multidimensional thing lying behind these factors.

Compare the rule of law to another notoriously difficult-to-measure concept, democracy. We might say that democracy is a multidimensional concept comprising, say, “political equality” and “popular sovereignty.” But the person who wants to do so owes us an explanation about why, if that’s the case, we ought, morally, to care about “democracy” at all, distinct from the independent reasons we have to care about “popular sovereignty” and “political equality.” If we’re consequentialists, we might think that having both popular sovereignty and political equality produces more good things than having just one, but that still doesn’t warrant saying that their combination is one good thing, rather than two good things that just happen to be better together. Put differently, salt is different from the mere combination of sodium and chloride. We enjoy consuming salt qua thing; we wouldn’t enjoy consuming a bunch of sodium and a bunch of chloride mushed together. The rule of law is an object worthy of study only if it’s one thing rather than just the mushing together of some other things. A multidimensional account of a social scientific phenomenon just begs the thoughtful researcher to reduce the concept to its dimensions.

By contrast, conceiving of the rule of law as a unidimensional concept also clears away some of the confusion about what particular items go into a measure of the rule of law. We can distinguish what the rule of law is from social phenomena that are either tools to achieve the rule of law or arguable consequences of it. Some of those things may still be worth including in a measure of the rule of law. For example, judicial independence is merely a tool to achieve the rule of law (it’s conceptually possible to have the rule of law without it), but it’s a very common and important tool, and given that we cannot observe the rule of law directly, it may be worthwhile to include judicial independence in a measure of the rule of law as a proxy. But we can do so consciously, without succumbing to the illusion that judicial independence is a component of the rule of law or a dimension of it.

In the foregoing chapters, I have given a conceptual and normative analysis of the rule of law as a unidimensional concept. There are three principles of the rule of law, but those principles are largely hierarchical: one must have regular legal rules constraining those in power for those legal rules to be public; one must have public legal rules for them to be general. The rule of law measure in this chapter takes advantage of the unidimensional properties of the underlying concept by taking existing data for the rule of law and composing them into a scale using the tools of item response theory (IRT). IRT is a method borrowed primarily from psychological research, which measures a unidimensional construct (a latent variable; in psychology, things like the big five personality traits, IQ, etc.) by measuring individual items (e.g., answers to a test), with the model that those who have greater degrees of the latent variable will also answer more of the items in the predicted way.

Some IRT models, like the Guttman scaling methods from which they were derived, suppose that the individual items exist in a hierarchy of difficulty that track greater or lesser degrees of that concept, such that we would ordinarily expect to see the more difficult items only in the presence of the less difficult items. (I will call these “hierarchical models.”) For example, if such a scale is measuring racial tolerance, we would expect everyone who answers “I would be willing to allow my children to marry people of other races” to also say “I would be willing to live in the same town as people of other races.” Likewise, on a test measuring mathematical knowledge, we would ordinarily expect correct answers to the calculus questions only on the tests that have correct answers to the arithmetic questions. IRT models improve on Guttman scales by being more accommodating of random measurement error, such that the results of an IRT model might deviate from a perfect Guttman scale.56

Such hierarchical models track the hierarchical properties of the rule of law, in that individual variables on the scale reflecting generality will be more difficult, in this sense, than items reflecting publicity, which in turn will be more difficult than items reflecting regularity. However, hierarchical models tend to depend on strong assumptions about item-by-item ordering. For example, the Mokken model of double monotonicity requires items that have a consistent difficulty ordering across all subjects.57 This is an implausible standard to meet in a rule of law index with multiple items tracking different parts of each of the three principles. For example, generality may be captured by variables measuring both the racial equality in a state’s laws and its gender equality; it may be that some legal systems are nongeneral with respect to race but not gender, and others are nongeneral with respect to gender but not race, even though all legal systems that are general with respect to either also satisfy regularity and publicity to a substantial degree. Accordingly, I make use of the Mokken model of monotone homogeneity, which benefits from substantially weaker assumptions. Monotone homogeneity requires only three assumptions: first, that there is an underlying unidimensional latent trait (this is the assumption on which the whole enterprise is based); second, that each item is more likely to be true (for polytomous items, to a higher degree) if the latent trait is found to a stronger degree (a fairly straightforward scale requirement); and third, that there are no omitted variables influencing scores on multiple items (“local stochastic independence”).58

2 Item selection and scale-fitting

Data from the World Justice Project’s 2012 expert and general population surveys were used.59 First, I personally reviewed the survey questions for their correspondence to the elements of the rule of law described in Chapters 1 and 2. Selected questions (items) were generally in the following categories: political influence and financial corruption in the judicial process, executive obedience to the law, opportunity for citizens to resist government power (included to capture the notion of coordinated defense by beneficiaries of law), discrimination in the criminal process, information about legal rights, and police misconduct. Unfortunately, the WJP data set contains little data on the substantive generality of the law, so data about discrimination in the criminal process will have to stand in for this principle as a whole. After this initial review, all items with missing data were removed, except where that missing data was clustered in one or a few states; on examination, four states were found to have an excessive amount of missing data and were removed from the data set. The resulting initial set of items contained 92 items across the 93 remaining countries.

Next, the data were fit to a Mokken monotone homogeneity scale (with minimum scalability coefficient H set to default at .3) using the genetic algorithm described by Straat, van der Ark, and Sijtsma, using the Mokken package for the R statistical programming language.60 All 92 items were found to fit the scale, with Cronbach’s alpha at .987. Finally, scores along each included item were summed across each country, yielding an ultimate rule of law score for each state, suitable at least for interpretation as an ordinal ranking. (These rule of law scores should not be interpreted as cardinal values.)

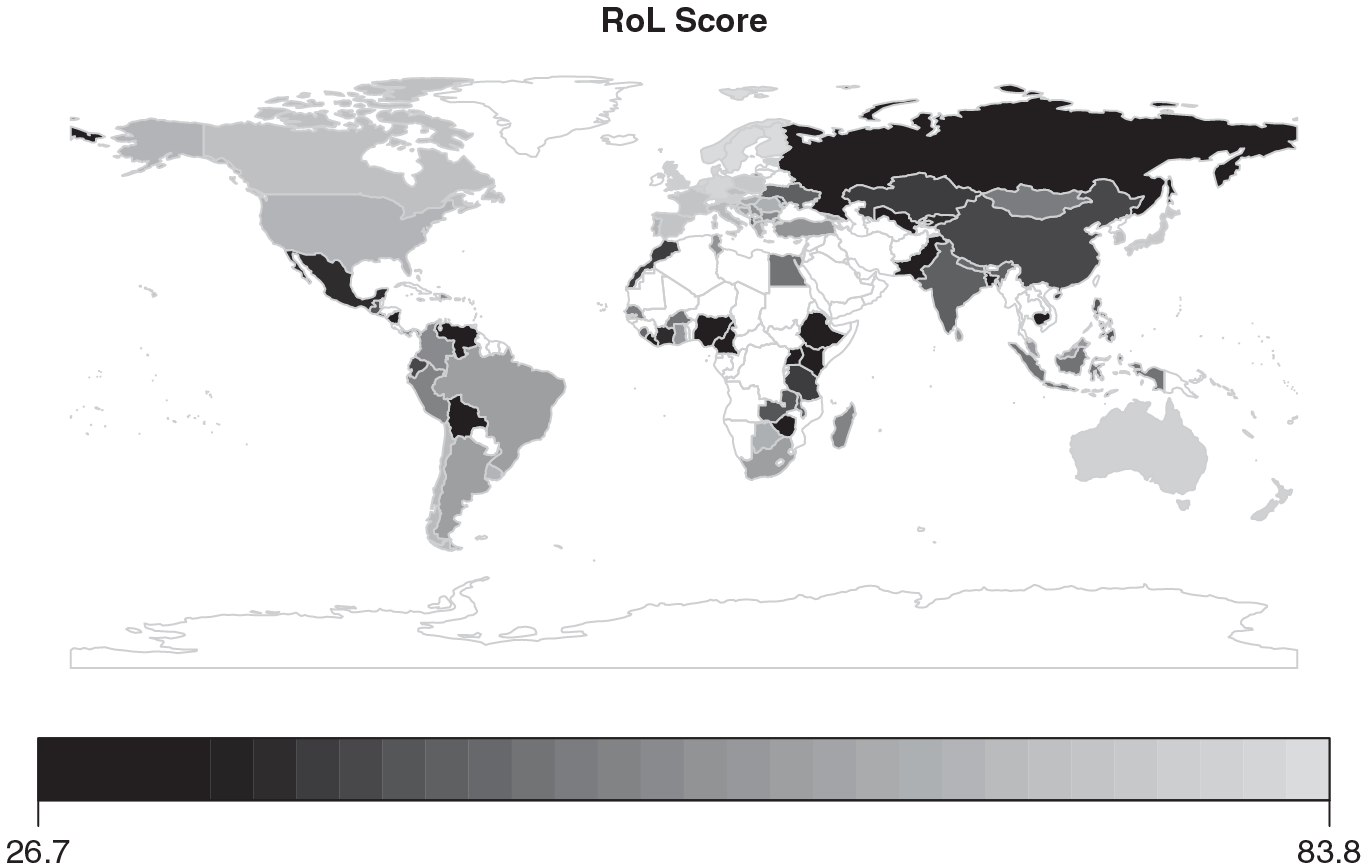

Each state’s rule of law score is included in an appendix to this chapter. Overall, total scores quite well match intuitive evaluations of the rule of law conditions of the most salient states in the world (see Figure 9A). On the whole, the North Atlantic liberal democracies and the most economically developed Asian nations rank the highest. For example, Sweden ranks first, the United Kingdom 11th, Japan 14th, the United States 26th, Iran 69th, Russia 79th, Venezuela 92nd, and Zimbabwe last.

Figure 9A Rule of law scores across the globe

B Limitations

The World Justice Project’s data set contains several inherent limitations for this task. First, it does not cover every country. Second, it does not contain extensive data capturing the generality principle; data considering, for example, the extent to which women and members of religious, linguistic, national, and/or racial minorities are subject to de jure or de facto legal discrimination would greatly improve the content validity of the scale given in this chapter. Third, the survey questions were not designed to fit a unidimensional model, and would be more useful had they been written with an intuitive scale of difficulty suitable for more hierarchical models. Fourth, the data do not measure public attitudes toward the legal system; direct data on public commitment to the rule of law would be highly useful. Fifth, the data were based on surveys connected between 2009 and 2012, depending on country, and political change between those years may make comparisons between countries surveyed in different years less reliable.61 The methods used here are also limited. The equal weighting of each scale item and the disparate number of items for the various principles of the rule of law may introduce distortions into the ultimate scoring.

C Behavior of the measure

Validating the proof of concept scale, we may note that it behaves in roughly the way expected by theory. In order to confirm its match to the rough theoretical consensus about the functions of the rule of law, I examined a series of bivariate regressions with indicators of economic development, individual freedom, and democracy. All are in the expected direction and are highly significant. Of course, this should not be taken as evidence that the rule of law itself is associated with these properties, as a proper inferential investigation would, among other things, include things like control variables. These regressions are merely reliability checks for the underlying scale: we would have reason to distrust a rule of law scale that was negatively associated with something like democracy or economic development.

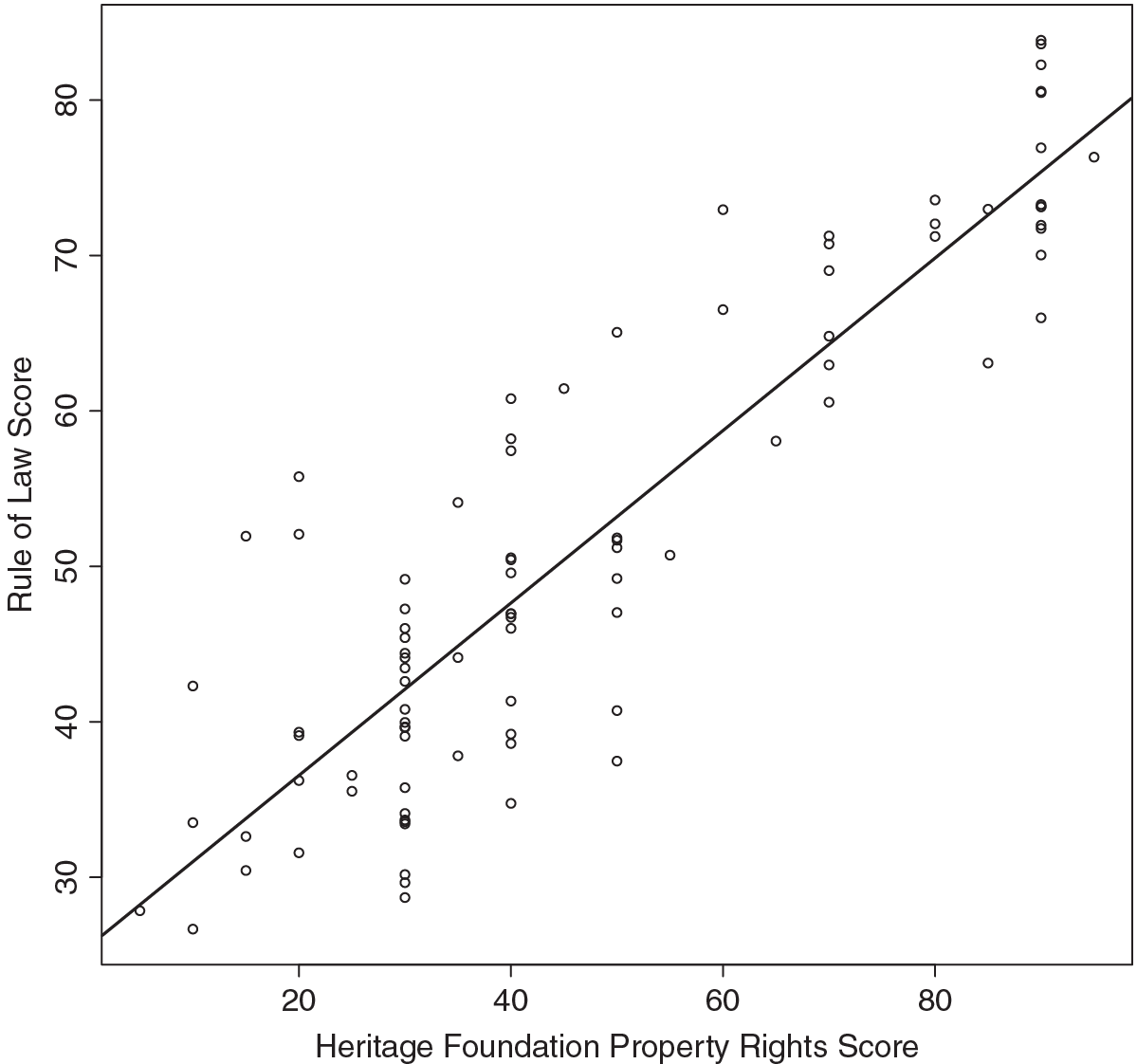

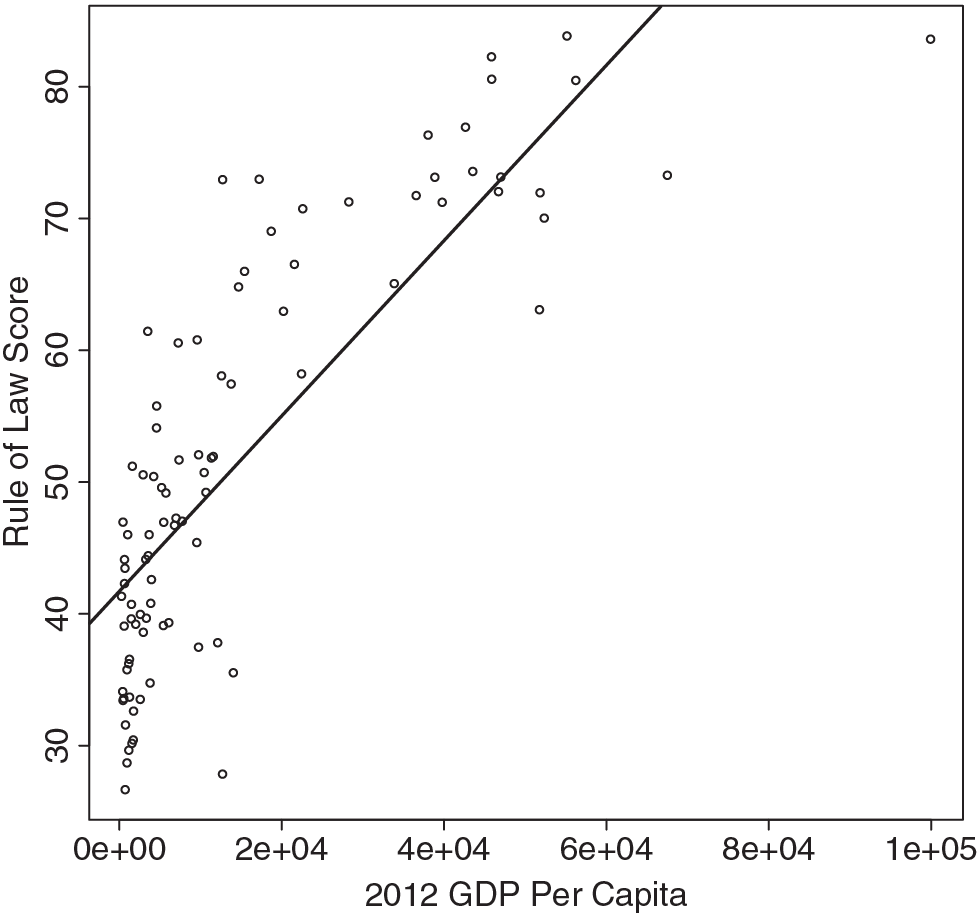

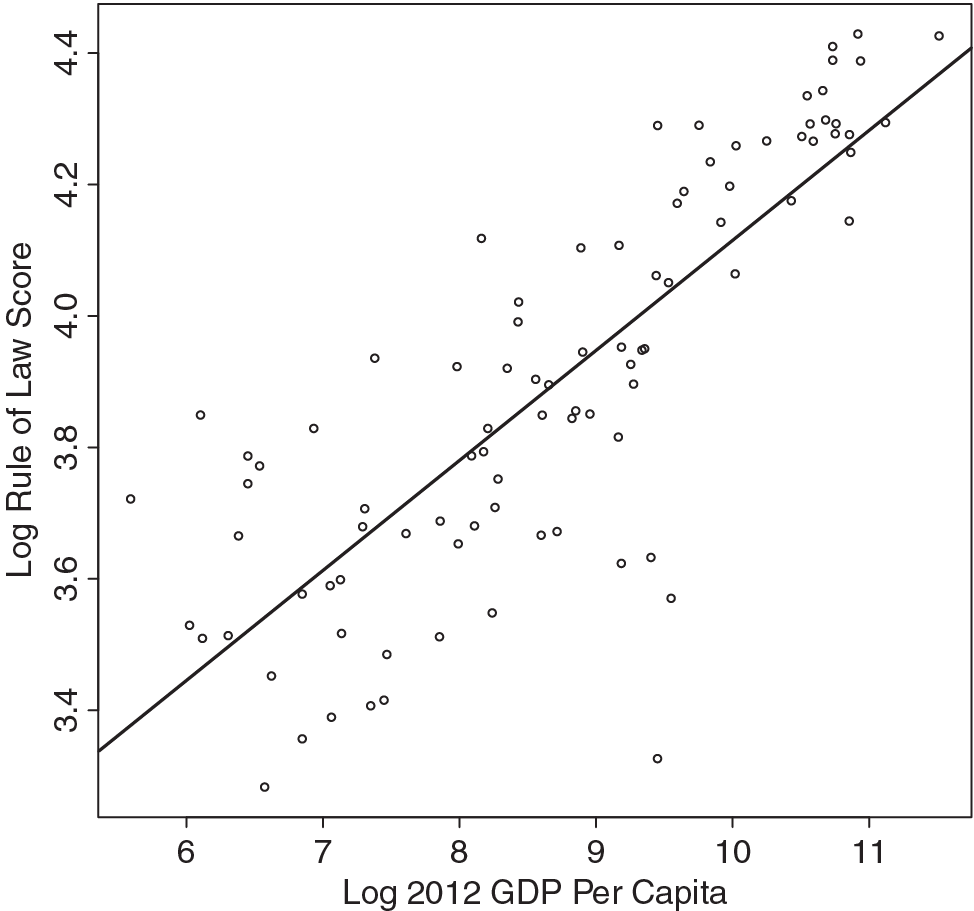

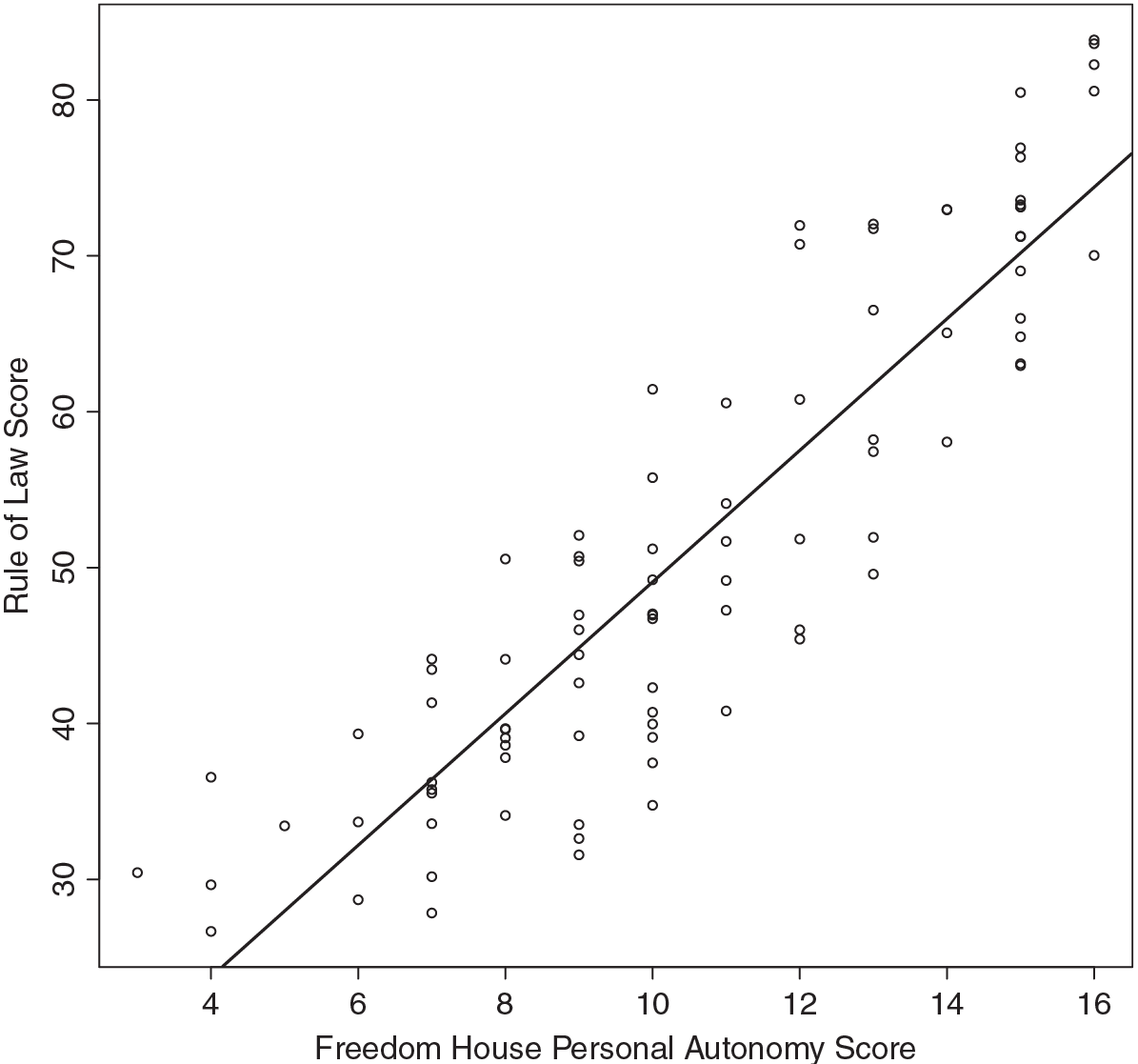

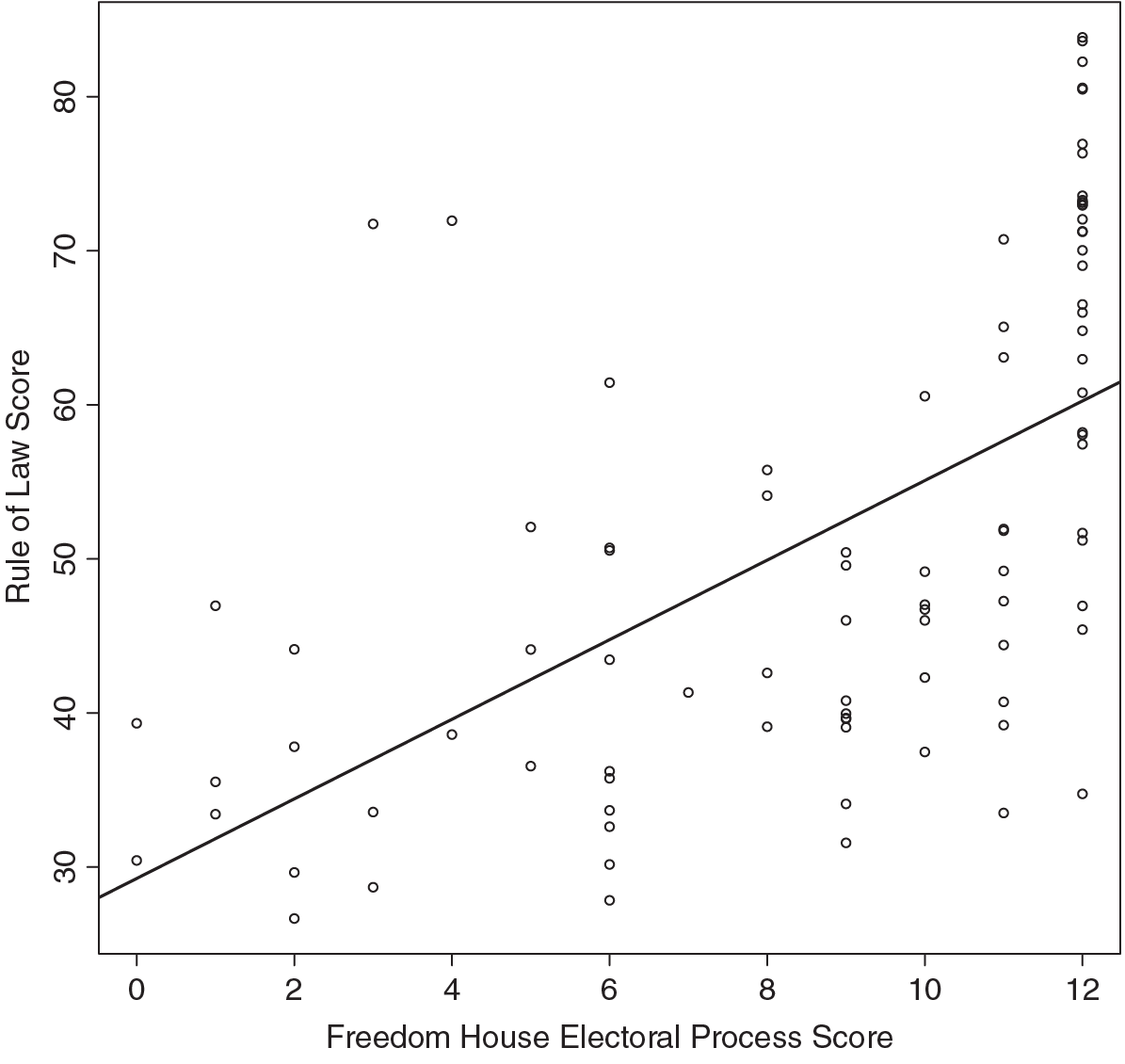

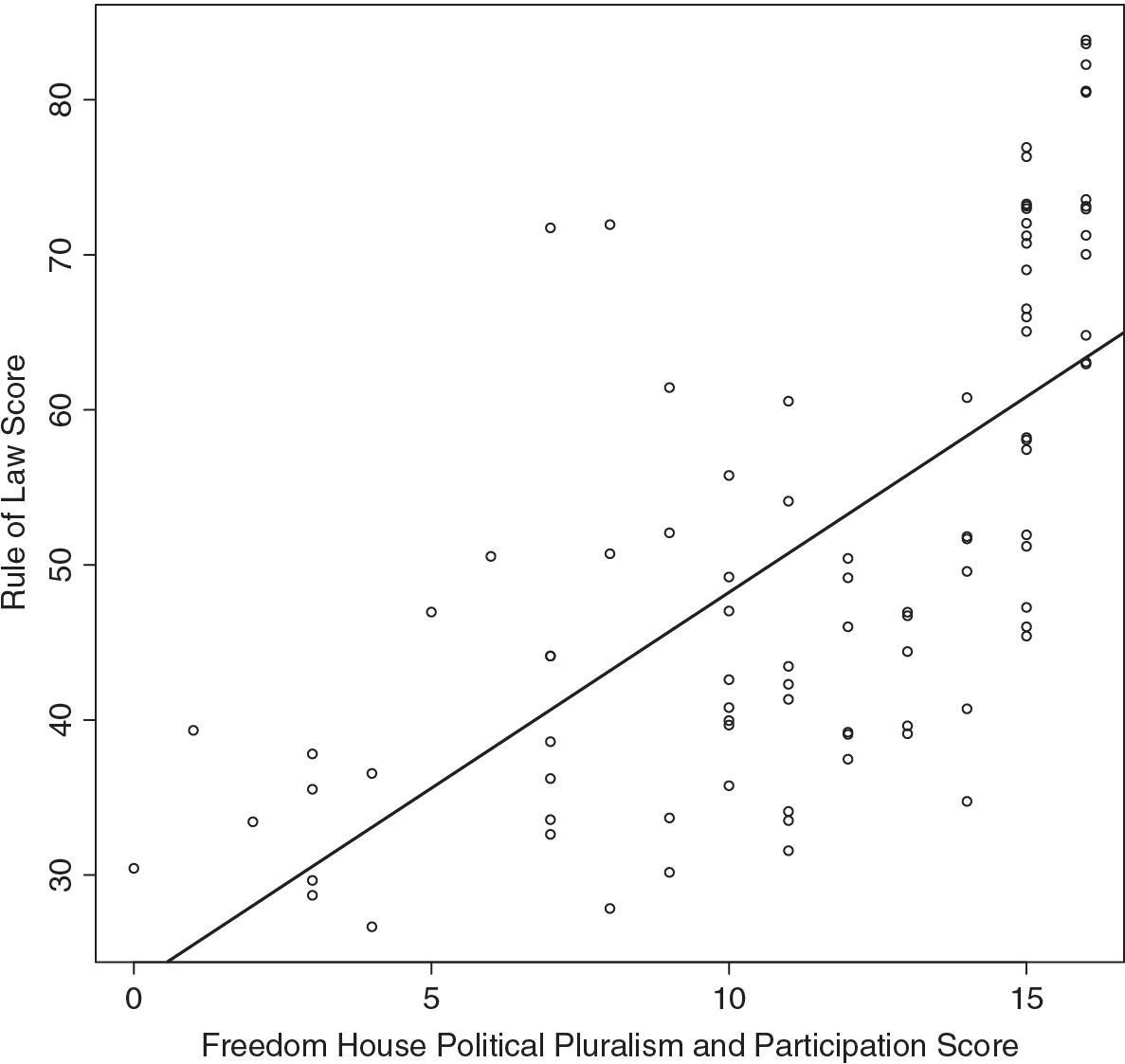

Accordingly, per capita gross domestic product (GDP) (from World Bank 2012 data) is a significant predictor of rule of law scores in a bivariate linear regression with p essentially indistinguishable from zero (values are listed in Table 9.1).62 The same is true of personal autonomy scores from Freedom House, Freedom House’s scores for states’ electoral processes and political pluralism and participation, and the Heritage Foundation’s scoring for the protection of private property rights.

Table 9.1 Bivariate regressions – rule of law scores

| RoL ~ | Coefficient | p |

|---|---|---|

| GDP Per Capita | 6.65 × 10−4 | < 2 × 10−16 |

| GDP P.C. (log-transformed) | 0.17 | < 2 × 10−16 |

| Personal Autonomy | 4.22 | < 2 × 10−16 |

| Electoral Process | 2.58 | 7.19 × 10−10 |

| Political Pluralism | 2.52 | 3.37 × 10−13 |

| Property Rights | 4.22 | < 2 × 10−16 |

Since the dominant theories in the social sciences suggest that the rule of law is more likely to be found in wealthy liberal democracies that protect property rights, the strong associations of the rule of law measure developed in this chapter with all of these indicators is good reason to think that it measures the variable of interest to political scientists, economists, and development professionals. Moreover, since that variable was constructed on the basis of survey questions that closely reflect the concept of the rule of law as developed by philosophers and lawyers, these results strongly suggest that the rift in the two rule of law conversations can be healed: social scientists can measure what normative and conceptual theory suggests the rule of law is, and it can give us some empirical traction on the questions of concern to real-world practitioners. A unified approach to the rule of law is possible.

III Appendix: Scores and states

This appendix contains several figures representing the results of the proof-of-concept rule of law measure. First, Table 9.2 is a complete listing of states, rule of law scores, and ordinal ranks. The graphs are scatterplots with fitted regression lines capturing bivariate relationships between the rule of law scores and various observable features often thought, in the theoretical domain, to relate positively to the rule of law. Figure 9B relates the rule of law to economic development, expressed as per capita gross domestic product (GDP); Figure 9C is the same as Figure 9B, but log-transformed to more clearly show the relationship given the scale differences between the variables and the clustering of GDP on the low end. Figure 9D relates the rule of law to a popular measure of individual liberty. Figures 9E and 9F relate the rule of law to two popular measures of democracy, expressed as the quality of a state’s electoral process (9E) and the extent of its political pluralism and participation (9F). Finally, Figure 9G relates the rule of law to a popular measure of a state’s level of property rights protection. Full color, interactive, and additional graphs are available online at rulelaw.net.

A Rule of law scores

Table 9.2 Rule of law scores by state

| State | Score | Rank | State | Score | Rank | State | Score | Rank | State | Score | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweden | 83.85 | 1 | Uruguay | 64.81 | 25 | Colombia | 47.03 | 49 | Morocco | 38.60 | 73 |

| Norway | 83.61 | 2 | United States | 63.08 | 26 | Madagascar | 46.96 | 50 | Kazakhstan | 37.81 | 74 |

| Finland | 82.27 | 3 | Portugal | 62.96 | 27 | Jamaica | 46.95 | 51 | Mexico | 37.47 | 75 |

| Netherlands | 80.57 | 4 | Georgia | 61.44 | 28 | Peru | 46.72 | 52 | Côte d’Ivoire | 36.55 | 76 |

| Denmark | 80.48 | 5 | Romania | 60.79 | 29 | Mongolia | 46.01 | 53 | Kyrgyzstan | 36.22 | 77 |

| Germany | 76.93 | 6 | Botswana | 60.56 | 30 | Senegal | 46.01 | 54 | Kenya | 35.76 | 78 |

| New Zealand | 76.33 | 7 | Greece | 58.21 | 31 | Panama | 45.41 | 55 | Russia | 35.53 | 79 |

| Belgium | 73.57 | 8 | Hungary | 58.06 | 32 | Indonesia | 44.41 | 56 | El Salvador | 34.75 | 80 |

| Australia | 73.28 | 9 | Croatia | 57.44 | 33 | Egypt | 44.13 | 57 | Liberia | 34.10 | 81 |

| Austria | 73.15 | 10 | Bosnia and Herzegovina | 55.77 | 34 | Burkina Faso | 44.12 | 58 | Pakistan | 33.68 | 82 |

| United Kingdom | 73.13 | 11 | UAE | 55.30 | 35 | Nepal | 43.46 | 59 | Uganda | 33.57 | 83 |

| Estonia | 72.98 | 12 | Macedonia | 54.11 | 36 | Albania | 42.60 | 60 | Bolivia | 33.51 | 84 |

| Poland | 72.95 | 13 | Lebanon | 52.07 | 37 | Sierra Leone | 42.30 | 61 | Ethiopia | 33.43 | 85 |

| Japan | 72.04 | 14 | Argentina | 51.94 | 38 | Malawi | 41.33 | 62 | Nicaragua | 32.62 | 86 |

| Singapore | 71.95 | 15 | Brazil | 51.83 | 39 | Ukraine | 40.80 | 63 | Bangladesh | 31.57 | 87 |

| Hong Kong | 71.74 | 16 | South Africa | 51.68 | 40 | India | 40.72 | 64 | Uzbekistan | 30.43 | 88 |

| Spain | 71.26 | 17 | Ghana | 51.20 | 41 | Philippines | 39.96 | 65 | Nigeria | 30.17 | 89 |

| France | 71.23 | 18 | Malaysia | 50.72 | 42 | Guatemala | 39.67 | 66 | Cameroon | 29.65 | 90 |

| South Korea | 70.74 | 19 | Sri Lanka | 50.55 | 43 | Zambia | 39.62 | 67 | Cambodia | 28.69 | 91 |

| Canada | 70.03 | 20 | Tunisia | 50.42 | 44 | China | 39.33 | 68 | Venezuela | 27.84 | 92 |

| Czech Republic | 69.03 | 21 | Serbia | 49.58 | 45 | Iran | 39.23 | 69 | Zimbabwe | 26.66 | 93 |

| Slovenia | 66.52 | 22 | Turkey | 49.22 | 46 | Moldova | 39.21 | 70 | |||

| Chile | 65.99 | 23 | Dominican Republic | 49.17 | 47 | Ecuador | 39.11 | 71 | |||

| Italy | 65.06 | 24 | Bulgaria | 47.26 | 48 | Tanzania | 39.07 | 72 |

B The rule of law and other measures of political well-being

Figure 9B Rule of law scores and per capita GDP

Figure 9C Log-transformed rule of law scores and per capita GDP

Figure 9D Rule of law and individual autonomy scores

Figure 9E Rule of law and electoral process scores

Figure 9F Rule of law and political pluralism scores