Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 January 2021

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

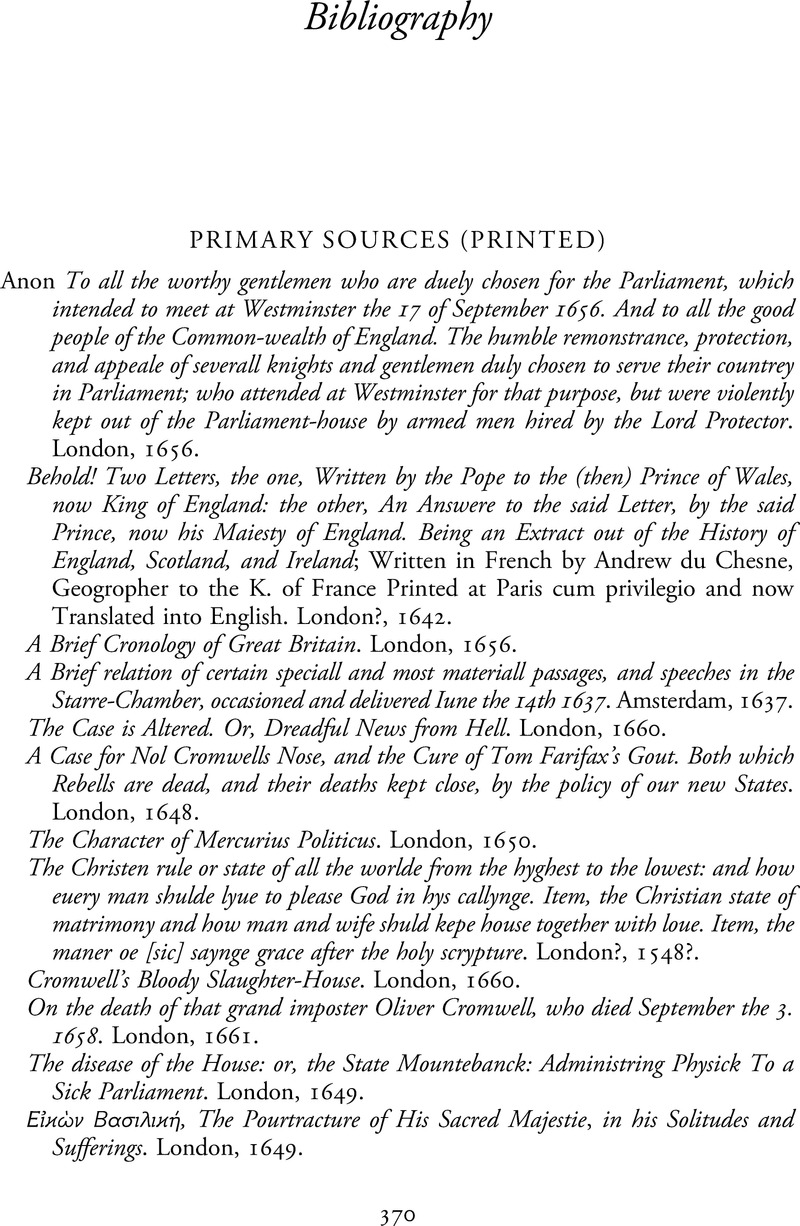

- The Rule of ManhoodTyranny, Gender, and Classical Republicanism in England, 1603–1660, pp. 370 - 412Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020