Welcome to Shakespeare’s Stages, a resource designed to introduce you to the key features of the theatrical spaces for which Shakespeare wrote his plays, in which he worked as an actor, and in which he had a financial stake. Like Shakespeare’s narrative sources, the members of his acting company, and the political climate of early modern England, these spaces had a powerful shaping influence on the conception, dramatic design, and performance of Shakespeare’s plays. The plurals peppered throughout these first sentences – stages, spaces – are important. For while popular images of early modern theatre aided and abetted by contemporary film and television – as well as the high-profile reconstruction of Shakespeare’s Globe on London’s Bankside – have often conveyed a sense that Shakespeare wrote for one fixed, open-air stage, the reality is rather different.

The notion of the ‘Shakespearean stage’ still frequently referred to by scholars is a fallacy. Throughout his career, Shakespeare wrote for, and acted upon, a number of different stages: at least four of London’s playhouses (three outdoor, one indoor); at the courts of Elizabeth I and James I; in at least one of the large inns in the City of London itself; in the halls of the Inns of Court; and, while on tour, on makeshift stages in a number of stately homes, town halls, and university buildings.

Known English touring venues for the Lord Chamberlain’s/King’s Men.

Though several of these spaces will at least be touched upon throughout this guide, we’ll focus chiefly on the two spaces Shakespeare part-owned: the Globe, a large open-air, polygonal structure erected on London’s Bankside in 1599, and the Blackfriars, a smaller, indoor playing space converted from the large hall of a medieval priory situated almost directly across the River Thames. In a unique arrangement, Shakespeare’s company, the King’s Men (known as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men until James’s accession in 1603), occupied both the Globe (in the summer) and the Blackfriars (in the winter) from 1609. These are the spaces for which Shakespeare wrote the majority of his plays. Given the early modern repertory system’s habit of bringing old plays back to life even decades after they were first written and acted, it is likely that most, if not all, of Shakespeare’s plays were performed at least once in one or even both of these playhouses.

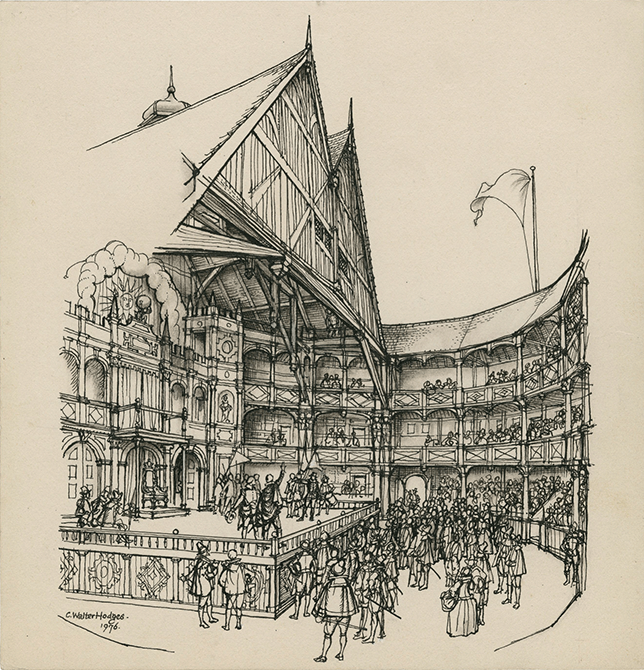

It would be ideal if history had gifted us an accurate picture of what each of these spaces was like. Sadly, that couldn’t be further from the case: we have no complete picture of any of the London playing spaces from the period, and much of what we (think we) know of the Globe and the Blackfriars can only been inferred from evidence relating to other playing spaces. Reconstructing these spaces requires piecing together fragments: chiefly, the architectural foundations of the Rose, Curtain, and Theatre playhouses, along with a tiny portion of the Globe, and a copy of a Dutch tourist’s sketch of the Swan playhouse’s interior. To these we can add a number of other pieces of ‘evidence’ – artists’ impressions of London as a whole, passing references in literary and other documents, and surviving building contracts – but these often make the picture more, rather than less, complicated.

Figure 2.1 The interior of the second Globe playhouse (built 1614) as imagined by C. Walter Hodges.

To make matters worse, each of these scraps of evidence offers something or other to contradict at least one of the others. What’s more, new archival and architectural evidence is emerging all the time – particularly since the turn of the twenty-first century – which sheds new light upon, but more often challenges, the ‘factual’ picture of the early modern playhouses. Envisaging ‘Shakespeare’s Stages’, then, requires a fair amount of educated guesswork, as well as a continuing willingness to revise our sense of what we ‘know’ about the spaces in which his plays came to life.