On the one hand, I think people think that the Constitutional Court and the law are very powerful things and then the other hand, do they really translate into effects for anyone?Footnote 1

The preceding chapters of this book theorized the concept of constitutional embedding and documented how both of its components – social and legal embedding – occurred in Colombia, such that the 1991 Constitution could weather strong challenges to its status and influence. The key argument of the book is that constitutional embedding is necessary for constitutional rights to be meaningful in everyday life. It holds that constitutional embedding comprises two dimensions: social and legal. The social dimension of constitutional embedding references the degree to which individuals and groups come to understand and relate to the Constitution in an intimate and everyday way, and legal embedding references the degree to which actors in the formal legal sphere accept and share a particular vision of constitutional law. Where the social and legal dimensions of constitutional embedding reinforce one another, a constitutional order will be likely to endure and difficult to dislodge.

This chapter, drawing on one year of fieldwork in South Africa – including eighty interviews with eighty-eight judges, lawyers, professors, and activists, an original survey, and participant observation – conducted between 2017 and 2018, extends the argument of this book to the case of the 1996 South African Final Constitution. In South Africa, we see clear evidence of legal embedding, with Constitutional Court justices and their law clerks – who would go on to serve as prominent members of the legal profession – adopting and developing a particular vision of constitutional law that would be at once responsive to citizens’ needs and largely deferential to the executive branch’s policy preferences. Social embedding, however, has lagged. While NGOs and legal aid organizations supported some litigants in harnessing the power of the law, rights claiming through the courts did not become a fixture of everyday life outside of law schools and courtrooms. Without each type of embedding reinforcing the other, the depth of the impact of constitutional change is limited. The constitutional text still promotes a transformative vision, but imagined – and imaginable – social and legal changes are hampered by this partial embedding.

9.1 Why Look to South Africa?

Colombia, South Africa, and India have long been held up as models of social constitutionalism (see, e.g., Bonilla Reference Bonilla2013). While the Indian constitution recognizes social rights only as directive principles, both Colombia and South Africa adopted new constitutions in the early to mid-1990s that recognized a wide range of rights, including social rights, and offered opportunities to make legal claims to those rights before new constitutional courts. The key difference between Colombia and South Africa in terms of their social constitutionalist impulses lies in the Colombian adoption of the tutela procedure that allows individuals to make rights claims without the need for a lawyer or the ability to pay fees. Judges must process these claims within ten days. While South Africa did adopt various strategies to increase access to justice, they fall well short of the tutela procedure in terms of speed and cost.

Further, Colombia and South Africa appear very similar with respect to the structural indicators measuring economic (upper-middle income and increasing) and human development (high and increasing), inequality (high and relatively stable), and levels of violence (high but decreasing) over the last three decades. Yet, even in the midst of these structural similarities, the two countries have been defined by substantially different state configurations, different party systems, and different historical legacies. The South African National Party implemented apartheid in 1948, developing a state that at the same time was highly legalistic, violent, and discriminatory toward nonwhite South Africans, while featuring an interventionist, welfare-oriented economy policy for white South Africans (See, e.g., Abel Reference Abel1995; Meierhenrich Reference Meierhenrich2010; Nattrass and Seekings Reference Nattrass, Seekings, Ross, Mager and Nasson2011). Just ten years later, a different form of exclusionary governance was formed in Colombia, with the National Front Agreement, which mandated power sharing between the Liberal and Conservative parties and further marginalized those outside of these traditional networks of power. Around the same time, guerrilla groups took up arms in a revolutionary challenge to the state (e.g., Palacios Reference Palacios2006; Tate Reference Tate2007). Apartheid and the anti-apartheid struggle indelibly marked South African political development, as did the protracted war between the revolutionary left and the state, albeit in different ways. Following the end of apartheid, the African National Congress (ANC) has dominated South African politics, certainly at the national level and to a large extent at the provincial level, rendering the country a de facto one-party democracy.Footnote 2 On the other hand, the historical dominance of the Liberal and Conservative parties in Colombia has faltered, with the Colombian party system veering toward deinstitutionalization (Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2006; Morgan Reference Morgan2013; Albarracín et al. Reference Albarracín, Gamboa, Mainwaring and Mainwaring2018).

Citizens in both Colombia and South Africa pushed for fundamental changes to the state, and especially its foundational legal order, in the early 1990s, and in response, policymakers adopted new constitutions in both countries. As in South Africa, Colombia had been historically defined by its longstanding – if differently operationalized – commitment to formalism in law. Yet, the combination of decades of war between leftist guerrillas and the state that showed little sign of abating, a consistently unresponsive legislature, and the emergence of a student movement, comprised largely of law students, resulted in demand for a new legal experiment that would ultimately recognize a new set of rights and empower the judiciary (Dugas Reference Dugas2001b; Lemaitre Reference Lemaitre2009). Interestingly, as Jens Meierhenrich (Reference Meierhenrich2010) demonstrates, in South Africa, features of the apartheid state actually promoted shared stabilizing expectations among the elites, many of whom trained as lawyers, about the role of law in the transition to inclusive democracy. In this context, a basic level of confidence in the idea of law and constitutional rights permeated throughout society, regardless of race. Further, the Constitutional Court – at least initially – was understood and understood itself to be engaging in a joint constitutional project with the other branches of government (Fowkes Reference Fowkes2016). Considering these factors, the empowerment of the courts, the recognition of social rights, and citizen trust in the legal process are less surprising that they might initially appear.

The rest of the chapter turns first to the emergence of social constitutionalism in South Africa, before looking to legal embedding and then social embedding. It closes with a discussion of the consequences of partial embedding.

9.2 The Emergence of Social Constitutionalism in South Africa

Much like the 1991 Colombian Constitution, the South African Final Constitution of 1996 (building on the 1993 Interim Constitution) set out a social orientation for law that its designers hoped would help the country to transform.Footnote 3 In South Africa, as in Colombia, transnational ideas about rights and constitutionalism – specifically regarding the entrenchment of social rights and the creation of constitutional courts – found fertile ground following domestic pressure for legal and social change (Klug Reference Klug2000). Various facets of the anti-apartheid movement called for a refounding of the South African state, specifically a fundamental change in the legal architecture of the state. During the constitutional negotiations, the language of internationally or “universally” accepted rights was commonplace. Political elites and appointed experts explicitly sought examples from international law, as well as from the Canadian Charter and the German Basic Law, setting the stage for the adoption of a social constitution. In what follows, I provide an overview of the debates around social constitutionalism during the constitutional negotiations of the early 1990s in South Africa, which will then allow me to assess the extent to which this vision of constitutional law has become embedded socially and legally in the country.

These negotiations took place between 1990 and 1993, and they included the Conventions for a Democratic South Africa and the Multi-Party Negotiating Process.Footnote 4 The resulting Interim Constitution of 1993 introduced judicial review, created the Constitutional Court, and established a Bill of Rights.Footnote 5 This Bill of Rights did not include robust social rights protections, but neither did it preclude them from being added later in the Final Constitution, which is precisely what occurred. Following the establishment of the Interim Constitution, a constitutional assembly consisting of both houses of the newly elected Parliament was convened to draft a Final Constitution, which would be certified by the newly created Constitutional Court.

As part of this final drafting process, the major political parties established several theme committees, which were tasked with providing expert advice on constitutional design questions, including on the inclusion and scope of rights protections. Theme Committee 4 handled these rights questions. The First Report of Theme Committee 4 in January 1995 notes that all of the parties to the Constitutional Assembly agreed in principle that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (1966) could “be used as important references for identifying universally accepted fundamental rights,” that “[t]he Bill of Rights should be entrenched, justiciable and enforceable,” and that the final list of included rights should not be limited to the rights listed in the Interim Constitution (41–42). This last point was important in that the Interim Constitution recognized a rather limited set of social rights (including basic education and an “environment which is not detrimental to … health or well-being”).

All of the major parties submitted documents outlining their preferences regarding constitutional rights protections to the Theme Committee 4. The ANC’s preliminary submission to the committee, entitled “Our Broad Vision of a Bill of Rights for South Africa,”Footnote 6 indicated deep support for a substantive set of social rights, as well as a clear role for the courts in helping to realize those rights (48–49). The Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) and Pan African Congress (PAC) also advocated for the inclusion of justiciable social rights, expressly noting that the Bill of Rights should be geared toward supporting the well-being of citizens. The IFP’s proposal suggested that the Constitution should allow for “the updating and evolution of human rights protections, which are historically an ever changing field of law,” and called for the Constitution to recognize “all fundamental human rights and all those other rights which are inherent to fundamental human needs and aspirations as they evolve with the changes and growth of society” (59).Footnote 7 The PAC called for the creation of “an institution modeled along the lines of the European Human Rights Commission” to help with what they called the “practical enforceability” of rights.Footnote 8

The Democratic Party, on the other hand, raised a number of concerns about the separation of powers and enforceability of rights. Their submission held that “policy formation – from the detailed provision of health services to the allocation of housing – is preserve of parliament, not the constitution” and suggested that relatively few civil and political rights be explicated in the Bill of Rights. They also noted, however, that “because the promises of a Bill of Rights could be empty, cruel words echoing in a wasteland of deprivation and denial, the Bill must provide for a standard of justification which empowers the citizen to obtain from government the entitlements to the means of survival” (51).Footnote 9 The National Party also raised strong concerns about social rights, stating that “the inclusion of more socio-economic rights [presumably beyond those included in the Interim Constitution] in the bill of rights itself, is legally untenable and will, moreover, give rise to immense practical problems for government” and advocated for the use of “alternative mechanisms” to address issues related to social rights, such as “directive principles” (66–67).Footnote 10

While there was significant disagreement as to the scope and application of the Bill of Rights in these initial submissions, it is important to note that all parties framed their proposals in terms of international human rights discourse, not as a result of coercion or even explicit suggestion by external actors, but as a result of a shared understanding among domestic elites of the legitimate sources of constitutional examples. Further, these debates were less heated than those regarding the question of land and property. As one expert involved in the drafting process as a member of the Technical Committee to advise the Constitutional Assembly on Drafting of Bill of Rights noted: “The debate on property rights was much more vigorous and intense … Social and economic rights went through quite easily. The ANC supported social and economic rights, and the Technical Committee was unanimous in its support … We did keep that very separate from the property rights issue.”Footnote 11, Footnote 12 In fact, the Technical Committee achieved early consensus. The same expert recalled: “The Committee unanimously supported the inclusion of socioeconomic rights in the Bill of Rights. That is how the decision was taken. And then came the drafting … We relied heavily on the Covenant [on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights].” He went on to say: “There was no great philosophical debate … We were all lawyers.”Footnote 13

Further, another expert advisor on the Technical Committee holds that by the time that the Constitutional Assembly negotiations were in full swing, “the debate at that point focused on the justiciability issue and where the courts should have a specific role” in the adjudication of social rights. That same expert also notes that for some, including many ANC members, “the idea was to see the Bill of Rights as a tool to transform society.” Others, including members of the National Party and the Democratic Party, were more skeptical (for varying reasons). However, there “was a convergence because they also saw [that] the more you’ve got in the Bill of Rights, the more protection there would be for minority groups as well.”Footnote 14 Generally speaking, then, elite political actors seemed to agree on the language of the debate (oriented toward existing international human rights law), and the experts appointed to advise these political elites expressed even less variance in their views on the potential Bill of Rights.

The Final Constitution was adopted in May 1996, with the support of nearly 90 percent of the members of the Constitutional Assembly, though it was almost immediately challenged in court, and the Constitutional Court refused to certify the text. The Court instead asked the Constitutional Assembly to review and revise eight sections of the constitutional text. In December, the Court certified the revised text, which entered into force early the following year.

As described in the previous chapters with respect to the Colombian experience, the adoption or certification of a constitutional text does not mean that it will necessarily become socially or legally embedding and shape social and legal behavior. One key difference between the Colombian and South African experiences is that the South African Interim and Final Constitutions of the 1990s were really the country’s first sustained forays into constitutionalism (though legalism was not a new phenomenonFootnote 15) and judicial, rather than parliamentary, supremacy. What would become of these efforts? I now turn to the uneven embedding of the South African Final Constitution of 1996.

9.3 Constitutional Embedding in South Africa

As detailed in Chapter 2, constitutional embedding refers to the process by which constitutions come to be meaningful in social and legal life. Legal embedding occurs as judges and lawyers come to have new shared expectations about a particular constitutional vision. They make legal arguments and issue decisions on the basis of constitutional provisions, including newly recognized rights, rather than other sources of law. Social embedding, on the other hand, involves potential claimants and other societal actors coming to make rights claims and view problems in their lives as legal grievances under the new constitutional framework. Empirically, legal and social embedding can combine in different ways. Where legal embedding accompanies social embedding, these processes become mutually reinforcing, as we saw in the case of Colombia described throughout this book. As will become clear throughout this section, in South Africa, by contrast, we see a high degree of legal embedding without concomitant social embedding.

9.3.1 Legal Embedding

I turn first to the question of legal embedding: to what extent were lawyers and judges impacted by the constitutional vision set out by the 1996 Constitution? In what follows, I offer an overview of social rights cases, which show that social constitutionalism did become legally embedded in South Africa. I then describe how legal mobilization and particular actions taken by the Constitutional Court facilitated this embedding process. This section closes with a discussion of embedding below the level of the South African Constitutional Court.

9.3.1.1 Legal Embedding at the Constitutional Court

I look to social rights jurisprudence to examine whether or not the legal embedding of social constitutionalism took place at all. If this kind of embedding did not occur at the level of the new Constitutional Court, we would not expect it at any level of the South African judiciary. The South African Constitutional Court has heard an average of just under three social rights cases each year (with a maximum of eight social rights cases in a given year) between 1996 and 2019, and of these cases, the majority have dealt with the right to housing. In fact, as of 2019, the Court had decided thirty-seven housing rights cases, compared to twenty-one education rights cases, eight social security cases, eight health cases, and two cases involving water. Overall, social rights cases make up about 9.5 percent of the Court’s work.

The first social rights caseFootnote 16 to come before the Court, Soobramoney v. Minister of Health (Kwazulu-Natal) (1997), involved a claim regarding the right to health advanced by a man suffering from kidney failure who was seeking access to a dialysis machine at a state-run medical facility.Footnote 17 In deciding the case, Judge President Chaskalson wrote:

There is a high level of unemployment, inadequate social security, and many do not have access to clean water or to adequate health services. These conditions already existed when the Constitution was adopted and a commitment to address them, and to transform our society into one in which there will be human dignity, freedom and equality, lies at the heart of our new constitutional order. For as long as these conditions continue to exist that aspiration will have a hollow ring.Footnote 18

He noted the “constitutional commitment” to address these conditions was expressed in Sections 26 and 27, which detail the rights to have access to adequate housing, healthcare, food, water, and social security and social assistance. Ultimately, the Court decided against Mr. Soobramoney, with Judge President Chaskalson concluding: “The State has to manage its limited resources … There will be times when this requires it to adopt a holistic approach to the larger needs of society rather than to focus on the specific needs of particular individuals within society.” In a concurring decision, Justice Sachs held that an acknowledgment of the dignity and equality of all citizens required the rationing of healthcare services.Footnote 19 Overall, this case challenged the Court to navigate a commitment to the realization of social rights and human dignity and a concern with balancing individual needs and collective consequences.Footnote 20

The next substantive social rights case, Government of the Republic of South Africa and Others v. Grootboom and Others, came before the Court in 2000.Footnote 21 This case involved the attempted eviction of 900 people living in a squatter settlement near the city of Cape Town. In the decision, Justice Zak Yacoob noted the centrality of dignity in South African constitutional rights jurisprudence, and held that “[s]ocio-economic rights are expressly included in the Bill of Rights; they cannot be said to exist on paper only.” This move can be interpreted as an attempt to indicate that social rights are meaningful in South Africa, despite the Soobramoney decision. Yet, how exactly rights would exist beyond their inscription on paper would be defined by judicial decisions. The Soobramoney decision made clear that they would not exist, at least in the judicial sphere, at the level of the individual claimant. The Grootboom decision further clarified a focus on the “reasonableness” of policy decisions, drawing on the phrase “reasonable legislative and other measures” included in the Constitution (reasonableness was not quite defined, though the decision did indicate that clear respect for human dignity would be integral to an assessment of reasonableness).Footnote 22 Ultimately, the Court found that the state’s housing policy was unreasonable and therefore unconstitutional because it neglected to provide for those in desperate need, and the decision mandated that the government develop an emergency housing policy. The justices of the Constitutional Court could have decided these cases differently, and many analysts and observers have suggested that they should have.

Social rights cases continued to make it to the Constitutional Court, numbering two or three per year through the early 2000s. Between 2000 and 2002, the Court considered three additional education-related cases, declining to hear one, deciding one on the basis of the minister of education’s powers (while explicitly refraining from addressing any constitutional rights questions), and relying on an analysis of just administrative action in the third.Footnote 23 In 2001, another housing-related case came before the Court, though the case hinged on whether or not the state could build a temporary transit camp on a specific piece of public land rather than on an interpretation of the meaning of the right to housing as such.Footnote 24

The next case that resulted in a substantive development to social rights jurisprudence was Minister of Health and Others v. Treatment Action Campaign and Others (2002).Footnote 25 The Treatment Action Campaign case involved the rollout of a state-led program meant to combat mother-to-child transmission of HIV through a medication by the name of nevirapine. Initially, the state wanted to make the medication available only at certain medical facilities (two per province), arguing that it had concerns about the safety and cost of nevirapine, though then President Mbeki’s AIDS denialism likely also played some role in this approach. The Treatment Action Campaign attempted to hone an argument focused on policy reasonableness (Heywood Reference Heywood2009), and the Court’s decision in this case once again affirmed the commitment to evaluating the reasonableness of policy designs. Unlike previous cases, this decision does not rely on an explicit assessment of dignity in its evaluation of policy reasonableness. Still, the case served as an important move for the Court in challenging a prominent national policy and in considering the right to healthcare as justiciable in practice like the rights to housing and education.

The Soobramoney, Grootboom, and Treatment Action Campaign cases are typically recognized as setting out the parameters of social rights jurisprudence in South Africa. Together, they point to an approach that combined a focus on policy choices – specifically the “reasonableness” of those choices – with respect for human dignity. Whether a policy was reasonable and whether it afforded sufficient protections to the dignity of South Africans would be decided on a case-by-case basis. South African judges made clear an aversion to firmly defining the substance or content of rights, which contrasts with the declaration of the Colombian Constitutional Court in T-406/92 that “today, with the new constitution, rights are what judges say they are through tutela decisions,” and contrary to the preferences of prominent civil society organizations and human rights lawyers, which favored the minimum core approach to outlining the content of social rights establishing in international law. As one former clerk and current advocate noted, “the way our Court interpreted its role made it very clear that it was secondary to the role of the elected representatives … I think it created a very restrained role for itself.”Footnote 26 South African judges focused on policies and processes, and on the societal rather than individual effects of decisions. Thus, we see legal embedding of the constitutional vision, but in a more limited way than was the case in Colombia.

As was the case with Colombia, we see a relationship between the continued exposure of judges to particular kinds of legal claims and the problems they implicate and judicial receptivity, especially when judges interpret these claims as consonant with contemporary sociolegal values. Again, the exposure mechanism refers to the process by which continued experience with claims related to a specific grievance cumulatively inform judges about an issue, causing them to become comfortable with the issue and to identify with claimants. The process can result in an increased receptivity of judges to claims pertaining to that issue area. We see this clearly in the realm of housing, where Constitutional Court justices connected the specific issue of access to housing with the general value of human dignity and steadily expanded the understanding of the scope of the right to housing. One former clerk currently working as a litigator at a Johannesburg-based NGO described the development of the right to housing as follows:

Under apartheid, it was illegal to be a squatter, and you could be kicked out and you could be thrown in jail … [Now] you [can] evict someone, but only with a court order, and only if it’s equitable … Built into the right is if eviction is going to lead to homelessness, the state must provide you with temporary alternative accommodation. And over the past twenty years, that has been expanded. It’s not just if you’re flood victim the state must provide this accommodation, it’s also if the state evicts you. Then the next step is when the state evicts you from private land. Then the next step, if a private owner evicts you, also you have this right. And now we’re getting to the content of what that alternative accommodation looks like … So, we’re seeing – and what’s so lovely and unexpected – is the Court has started writing case law on this, kind of like a handbook for litigators … The jurisprudence has developed to such a level that the courts are now writing, “Judges, when they decide this issue, have to do X, Y, Z.”Footnote 27

Another former clerk suggested that:

Housing cases are numerous at this point in the jurisprudence, in the High Court and the [Constitutional] Court, and I think that maybe it’s just getting judges and courts comfortable in that terrain so that the more of a particular kind of case they see, the more comfortable they become with the numbers and statistics and so on … Especially in the [Johannesburg] courts they’ve seen it again and again and again so they’re becoming more comfortable. I don’t know … [but] that’s something that I suspect.Footnote 28

This view is consistent with hands-on interventions undertaken by the Court in housing cases such as Residents of Joe Slovo Community, Western Cape v. Thubelisha Homes and Others (2009), which specified “the exact time and manner and conditions” of the eviction, including precise directives about the alternative accommodation to be provided to those subject to eviction.Footnote 29 The existence of a robust support structure around housing issues and the fact that eviction orders must be granted by judges meant that judges would continue to be exposed to housing rights cases. Another former clerk pointed to this support structure and the history of land and housing issues in South Africa as being particularly influential on the judicial receptivity of these kinds of claims:

There’s a long history of land and housing litigation as kind of an anti-apartheid move … A lot of the liberal and progressive judges who went on to High Courts and the Supreme Court of Appeal and the Constitutional Court identified with these cases as sort of, as sites of progressive fighting. I think [that] is one reason. There’s been incredibly organized and coordinated litigation and planning around housing rights specifically … There’s this kind of feedback happening between an issue that is obviously quite dire on the ground … [and] good organization among clients, lawyers, and receptiveness on the part of judges.Footnote 30

Yet another former clerk noted that the problem of inadequate housing was visible in such a way that judges were exposed to it, such that “even judges can see them for themselves.”Footnote 31

Still, exposure is not enough on its own to precipitate judicial receptivity. Judges must also have the sense that the kind of rights violation in question is incompatible with contemporary sociolegal values – in this case, the value of human dignity is crucial. In early health rights cases, including Soobramoney and Treatment Action Campaign, South African judges suggested that while human dignity remained central to the post-apartheid South African legal order, the link between a difficulty with access to healthcare might not be an infringement on dignity (in Soobramoney) or they simply did not consider dignity as a fundamental part of the legal analysis (in Treatment Action Campaign).

In contrast, in early housing rights decisions, human dignity featured prominently. For example, in Grootboom, Justice Yacoob wrote: “The case brings home the harsh reality that the Constitution’s promise of dignity and equality for all remains for many a distant dream.” Here, dignity and access to adequate housing are understood as necessarily connected, and this understanding combined with exposure spurred judicial receptivity to housing claims. This receptivity involved not only hearing housing rights cases but also issuing interventionist decisions, rather than leaving the issue to be resolved by the executive or legislature (even if those same judges otherwise embrace a philosophy of judicial deference). These decisions, particularly as they detailed what one lawyer quoted earlier described as “a handbook for litigators,” served as cues for potential claimants and incentivized further legal claim-making related to the right to housing, forming a positive feedback loop. By examining these social rights cases, we see evidence of legal embedding of the 1996 Constitution and its social rights provisions, particularly at the level of the Constitutional Court.

9.3.1.2 Legal Embedding beyond the Constitutional Court?

Considering that South African law changed not only in the adoption of a new constitution that set out a social vision for law, but also in the shift to constitutional supremacy in itself, we might think that the legal embedding faced an even steeper challenge among the legal community working below the level of the Constitutional Court. Here, I turn primarily to interviews with fifty current and former Constitutional Court clerks, many of whom later would go on to work as attorneys or advocates, at private firms or for NGOs, throughout the country. Their experiences both at the Constitutional Court and engaging in litigation across the lower courts offer a perspective on the broader judiciary and legal profession in South Africa.

Some clerks expressed the view that social constitutionalism has not been accepted throughout the judiciary. One former clerk and current member of the Johannesburg Bar explained that she has witnessed what she called “compassion fatigue” among judges at the high courts, especially when deciding eviction cases. She continued, “I think it’s judges who are tired of what they see as people using their rights to gain unfair or untrue benefits or advantage … That’s my experience and that’s of course not the case of all judges but there is a definite sense that of fatigue for judges for cases brought by NGOs trying to enforce constitutional rights.”Footnote 32 Here, repeated exposure to certain evictions/housing rights claims seems to have had the opposite impact to the one we saw on justices of the Constitutional Court. In the absence of a perceived connection to contemporary sociolegal values, namely human dignity, repeated exposure in these cases may have led not to receptivity but to its opposite.

There is also the perception that some older lawyers and judges, who came of age in a time without a constitution and without social rights recognitions, do not view constitutional law as proper law. Many clerks spoke of there being something of a split bar, with “black letter lawyers” on the one hand and constitutional lawyers on the other. Where these clerks disagreed, though, was on the extent to which this divide remains. Expressing the view that the divide persists, one clerk held:

There’s been a selective trickle down. And some people have really taken it onboard and others not at all. I mean some of the ones who’ve not at all are just kind of old and set their ways. But there’s also still I think a split about the perception that, you know, you have hard commercial law and then your wishy-washy constitutional law and I think some judges themselves probably secretly hold that belief and will avoid applying the Constitution if they can.Footnote 33

Other former clerks, though, suggested that the legal culture has changed over time, especially around the idea of (social) constitutionalism. For instance, one explained:

Many of those [early] High Court decisions had to be set right by the Constitutional Court because those judges weren’t imbued with that sensitivity [to the Constitution] … I do think that that has changed quite fundamentally in the last fifteen years. It has filtered down. I mean, you still have renegades, but the general idea that all law must be viewed through the prism of the Bill of Rights, for example, and that it must be infused with it, is something that is generally understood and practiced … Everyone understands that it is infused in the system.Footnote 34

Another similarly noted that years ago, constitutional law “was seen as an option [not an obligation]; ‘I don’t actually have to consider the Constitution,’ whereas now, especially with the younger lawyers or judges, they are aware that everything starts with the Constitution.”Footnote 35 Another summarized the present state neatly: “I do think that there is a willingness of judges on all levels to consider constitutional arguments, they know they have to.”Footnote 36 In the view of these former clerks and current advocates, a legal embedding of the 1996 Constitution has occurred throughout the South African judiciary, though others did suggest reasons for skepticism about the extent of embedding.

Overall, then, we see that although fewer social rights cases came before the South African Constitutional Court than in Colombia, Constitutional Court justices did come to adopt the 1996 Constitution and pursue its social ends. They developed robust standards for eviction cases and institutionalized protections for folks facing evictions. Compared to the Colombian Constitutional Court, they took a more restrained approach to other social rights issues, but as James Fowkes (Reference Fowkes2016) argues, this approach signaled the justices’ view that they shared the task of constitution-building and transformation with the executive and legislature. The Court did not express wholesale reluctance about or disregard for the new constitution; instead, they saw themselves as having a more limited role than their Colombian counterpart. Lower-court judges were perhaps initially hesitant to embrace social constitutionalism – or constitutionalism in any form – but over time, that hesitance appears to have given way to the application of constitutional provisions and principles.

9.3.2 Social Embedding

Legal embedding is only part of the story, however. Without social embedding, the flow of claims that come before the courts will be quite limited in both quantity and scope. So, to what extent has the vision set out by the 1996 Constitution permeated broader social life? Do everyday citizens have knowledge about the constitution, or is that limited to a select few who have close connections to NGOs? Do most citizens talk about the Constitution and their rights with familiarity? Do they believe they can make legal claims to their rights? Do they actually do so? I first consider how citizens may have been exposed to the 1996 Constitution and the work of the newly created Constitutional Court, before assessing these questions about social embedding in South Africa.

The drafting process of the post-apartheid constitution was met with both international fear and fanfare. Would South Africans be able to work within formal institutions to refound the country, or would extra-judicial violence rule the day? Of course, South Africans were intimately aware that a political transition was occurring, and most had strong feelings about the transition. Whether or not this general interest translates to specific knowledge about the constitution-drafting process or the nature of the new constitution’s new rights provisions is less obvious.

I first look to the major forums through which the constitutional designers sought to include the general South African public: media campaigns, public submissions, and public meetings (also known as “the constitutional roadshow”). The Constitutional Assembly put together a weekly television show called Constitutional Talk, which featured a panel discussion on various issues related to the new constitution (rights, separation of powers, etc.). A newsletter by the same name featuring both articles and comic strips circulated twice per month. In addition to the television show and newsletter, the assembly also sponsored radio programs and paper advertisements across the country.

The Constitutional Assembly solicited public submissions in the form of signed petitions and written requests, which, in theory, could propel both interest in the new constitution and subsequent constitutional buy-in, if the public felt that the new constitution truly reflected their input. Paul Davis, who worked in the submissions department, explained the procedure:

Every morning, Box 15, Cape Town, 8000, is emptied and all the letters are opened and date-stamped. Then they are taken to the submissions department where they are sorted into subject matter and placed in boxes. Those that are in languages other than English are sent for translation and all handwritten submissions are retyped.Footnote 37

In total, the assembly received over 1.7 million submissions (Segal and Cort Reference Segal and Cort2012), though the vast majority of the submissions were individual signatures in support of petitions. Around 15,000 featured substantive written suggestions from individuals or civil society groups (Gloppen Reference Gloppen1997). Figure 9.1 shows three of these submitted and retyped appeals. In her analysis of the substantive written submissions, Siri Gloppen (Reference Gloppen1997: 259) found that “a disproportionate share of the submissions seem[s] to come from the well-educated, the middle class, former politicians, academics, professionals and political activists.”Footnote 38 While potentially a concern for matters of legitimacy and representation, this kind of distortion does not necessarily cut against the possibility of social embedding. If this group came to adopt the resulting constitution as their own, spread the word about new rights and new legal tools, and push forward rights claims, then widespread social embedding could follow from this more limited beginning. After reviewing these submissions, the constitutional debates, and the resulting text, Gloppen (Reference Gloppen1997: 263) concludes, however, that “the millions of submissions from the public had little direct influence on the outcome of the constitutional-making process.”

Figure 9.1 Written submissions to the South African Constitutional Assembly.

Beyond the media campaign and submissions requests, the Public Participation Program of the Constitutional Assembly sought to bring the constitution-drafting process to the people. They convened more than twenty meetings throughout the country in 1995. Attendance at each of these meetings ranged from 130 to 4,000.Footnote 39 South African History Online reports that over 20,000 people and over 700 organizations participated in these meetings.Footnote 40 Alexander Hudson (Reference Hudson2021: 58) notes that “the Constitutional Assembly did go to great lengths to hold public meetings in very remote parts of South Africa, including the sparsely inhabited Northern Cape. The transcripts of the public meetings describe well-planned and orderly engagements between members of the public and members of the Theme Committees.”

In addition, the justices of the Constitutional Court worked to publicize their decisions after the 1996 Constitution went into effect, offering another opportunity for South African citizens to learn about the Constitution and its functions. Integral to these outreach efforts were the formation of a media committee and the introduction of television cameras into the courtroom. In an interview, former Justice Goldstone recalled:

We had seminars with senior journalists. We had annual meetings with the editors of the main newspapers and a lot of things came together from that. One of them was issuing a press summary together with judgments. The summary was drafted by the judge who wrote the lead opinion. That was very useful for the journalists … because, you know, sometimes it was a 150-page judgment.Footnote 41

These press summaries allowed journalists to more easily engage with potentially complicated legal decisions and translate what the Court was doing to the public. Further, because the South African Broadcasting Company carried court proceedings that were almost live, citizens – at least those with access to a television – could see the Court in action and learn about its work for themselves.Footnote 42 In these ways, the Court attempted to close the gap between citizens and constitutional law.

These efforts, however, were not clearly successful over the long term. In 1995, the Community Agency for Social Enquiry (CASE) and Roots Marketing were tasked with assessing the media strategy of the Constitutional Assembly. They found that 60 percent of respondents had heard of the Constitutional Assembly (and therefore the constitution-drafting process) by mid-1995. The report notes that “while three-quarters (76%) of respondents first heard of the [Constitutional Assembly] via mainstream media, 12% were first informed of it by word-of-mouth (from a friend, at work, at school and so on).” CASE concludes that the Constitutional Assembly “campaign has been able to achieve one of the key goals of a social education media campaign, namely to generate interpersonal communication, and enter popular discourse” (1995: 4). Yet, in 2015, only 10 percent of the population had read the final document put out by the Constitutional Assembly, the 1996 Constitution, or had it read to them (Fish Hodgson Reference Fish Hodgson2015: 191). And by 2018, only 51 percent of South Africans reported that they had heard of the Constitution or the Bill of Rights in 2018, up from 46 percent in 2015 (FHR Report 2018: 38). Tim Fish Hodgson (Reference Fish Hodgson2015: 190) notes that “statements of regret about the dearth of knowledge about constitutional rights have been a constant refrain of the Constitutional Court ever since its inception.” Many of the justices, clerks, and lawyers I interviewed in 2017 and 2018 echoed this concern. We might expect that knowledge and familiarity with the Constitution and the Constitutional Court would drop after the hubbub around their creation dies down. Together, these findings are indicative of a lack of exposure to the 1996 Constitution among everyday South Africans.

Further, relatively few South Africans have sought to make social rights claims, and not only because of this limited exposure to the contours of the constitution.Footnote 43 Many South African citizens do not find this kind of claim-making “thinkable,” a term that Kira Tait introduced to sociolegal studies scholarship. Even beyond traditional barriers to access to justice (e.g., precise knowledge about how to initiate a legal case, the material and time costs of litigation, and proximity to courthouses), people must be able to imagine making a legal claim. The ability to imagine making a claim can be broken down into a variety of constituent beliefs, including whether or not individuals believe they are technically able to make claims, whether or not people view the law as something that could or should work for them, whether or not they conceive of their problems as potential legal grievances, and whether or not they perceive courts as a resource they should use to address those grievances (Tait and Taylor Reference Tait and Taylor2022).

To explore legal claim-making perceptions and practices, I draw on an original 551-person survey fielded in South Africa in November 2017 (Taylor 2020b). The survey was available in four languages: English, Tswana, Xhosa, and Zulu.Footnote 44 Respondents were not selected on the basis of race, but survey respondents largely reflect national statistics on racial group membership.Footnote 45

I sought to sample respondents who had prior legal system experience and respondents who did not. As such, the survey did not rely on a standard random sampling design. Instead, I used two alternative sampling procedures. First, I attempted to oversample individuals with legal system experience. With the help of a South African NGO, I identified three of what I call “claimant communities,” located in provinces across the country. These communities are the informal settlements of Ratanang, Marikana,Footnote 46 and Thusong.Footnote 47 Each community was either presently involved in housing rights litigation at the High Court level or had been involved in such litigation in the previous five years.Footnote 48 The communities (residents of x location) were named as litigants in these cases. Individuals living in the claimant communities may or may not have identified as claimants, but my hunch was that a larger percentage of these individuals would report having legal system experience than what we see in the general population.Footnote 49 This hunch was borne out: while about 9 percent of respondents sampled from the general identified as having legal system experience, about 31 percent of claimant community members reported such experience.Footnote 50 Second, I randomly sampled respondents from the three provinces in which the three claimant communities are located: Gauteng, North West, and Western Cape. Every respondent was randomly sampled, regardless of which sampling strategy was used. However, individuals from claimant communities were more likely to be selected than respondents living elsewhere in the provinces. My intention is not to compare provinces or make generalizable claims about all of South Africa – both are inappropriate given my sampling strategy. What I hope to do, instead, is to conduct an initial investigation into claim-making behavior.

The survey asked about experiences with problems related to housing, water, sanitation, electricity, work, education, and health. I chose these seven social welfare goods for their connection to the basic necessities of daily life. Each of these goods can be understood in the context of the 1996 Constitution, or, stated differently, problems related to accessing these goods could be understood as rights violations. The right to adequate housing is enshrined in Section 26 of the Constitution, and this right has been referenced in cases about both sanitation and electricity. Both water and healthcare are covered by Section 27 (as is food and social security). Rights associated with access to employment and employment conditions fall within Sections 22 and 23. Finally, Section 29 lays out the right to education. Of course, not every problem related to these goods will entail a constitutional rights violation, but I wanted to err on the side of overinclusion of potential rights violations.

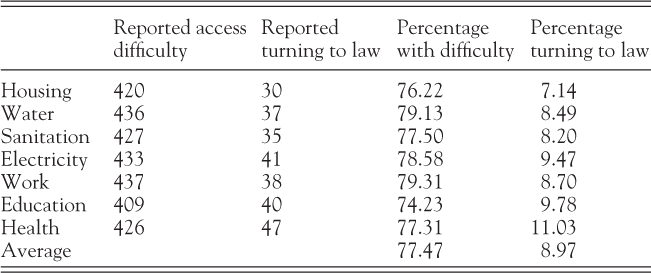

Roughly three-quarters of survey respondents indicated that they had problems related to each of these seven social welfare goods. I also asked how respondents reacted to the problems they faced: did they do nothing, ask friends and family for help, turn to the law (operationalized as talking to a lawyer, entering into litigation, or filing a formal complaint with the Human Rights Commission) or to public officials, or participate in protests? Unsurprisingly, most respondents noted that they “lumped” their grievances, doing nothing to resolve the problem (Galanter Reference Galanter1974). Even so, other respondents engaged each of the other strategies that the survey asked about. Figure 9.2 shows the responses by issue area.

Figure 9.2 Reported response to difficulties in accessing social welfare goods.

The survey also asked whether or not respondents agreed with the following statement: “If my rights are violated, I should file a legal claim, because the government has the obligation to protect my rights.” In the results, 183 (33.2 percent) of respondents reported strong agreement and 263 (47.7 percent) reported that they agreed with the statement. However, while about 80 percent of those surveyed said one should file legal claims in response to rights violations, only about 9 percent of respondents who faced difficulties accessing social welfare goods indicated that they had actually brought claims to the courts. Table 9.1 breaks down these findings by issue area. Not everything that could be thought of as a rights violation will be – that is why rights consciousness and legal consciousness cannot be assumed. And there are often disconnects between what people say they would do and the things they actually do. That there is a gap between these things is not in itself surprising. We can conclude, however, that – at least with respect to certain kinds of rights claims – survey respondents do view the legal system as a venue in which claims can or should be made, but it does not appear to be “thinkable” for respondents to bring social rights claims to the courts. Tait (Reference Tait2022) finds similar results in her interviews with rural and peri-urban Black South Africans in KwaZulu-Natal province.

Table 9.1 Likelihood of turning to the law to deal with a social rights difficulty

Reported access difficulty | Reported turning to law | Percentage with difficulty | Percentage turning to law | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Housing | 420 | 30 | 76.22 | 7.14 |

Water | 436 | 37 | 79.13 | 8.49 |

Sanitation | 427 | 35 | 77.50 | 8.20 |

Electricity | 433 | 41 | 78.58 | 9.47 |

Work | 437 | 38 | 79.31 | 8.70 |

Education | 409 | 40 | 74.23 | 9.78 |

Health | 426 | 47 | 77.31 | 11.03 |

Average | 77.47 | 8.97 |

This gap in the “thinkability” of legal claim-making does not mean that there is no claim-making for constitutional rights through the courts or no rights talk.Footnote 51 Indeed, the previous section on legal embedding outlined how social rights cases have been decided over the last thirty years in South Africa. Social rights cases do come before the Constitutional Court and decisions on these cases do have significant impacts on peoples’ lives. However, unlike in Colombia, these cases usually involve a collective actor rather than an individual, backed by NGOs, pro bono legal services, and/or movement organizations. Legal claim-making, therefore, is more centralized and mediated in South Africa than it is in Colombia. In Colombia, the diffuse ability of individuals to make legal claims meant that social embedding could spread rapidly, as folks across the country and across swaths of life were able to experience the power of the new constitutional promises for themselves. Legal claim-making in South Africa, under these circumstances of centralization and mediation, has not served to bolster social embedding and propel continued claim-making.

9.4 The Consequences of Partial Embedding

Unlike in Colombia, where social and legal embedding occurred together and reinforced one another, in South Africa we see one form of partial embedding: legal embedding without social embedding. Why was this the case? There are important institutional differences between Colombia and South Africa, most notably the absence of the tutela procedure in South Africa. We might think that the relative dearth of claims and limited constitutional literacy might be a consequence of this difference. It is easy to make constitutional rights claims in Colombia and less so in South Africa. But there is a direct access mechanism in South Africa. The 1996 Constitution sets out that: “National legislation or the rules of the Constitutional Court must allow a person, when it is in the interests of justice and with leave of the Constitutional Court to bring a matter directly to the Constitutional Court.” What constitutes the interests of justice is left up to interpretation. Jackie Dugard (Reference Dugard2015: 116–17) analyzed direct access petitions to the Constitutional Court between 1995 and 2013 and concluded that the following four principles guide decisions about whether or not to accept these petitions:

Exceptional circumstances;

Undesirability to sit as a court of first and last instance especially where there are disputes of fact;

Urgency/desirability of an immediate decision; and

Reasonable prospects of success based on the substantive merits of the case.

The Court denies the vast majority of direct access petitions, usually on the grounds of more than one of these principles. Ultimately, these decisions have meant that the mechanism has a limited scope. Dugard (Reference Dugard2015: 124) estimates that the Court accepted only eighteen direct access petitions between 1995 and 2013. Clearly, direct access petitions do not function the same way as the tutela does, and the direct access mechanism was never designed to mimic the tutela.

However, to focus only on the differences in the design of these mechanisms misses the point. Neither mechanism was meant to allow citizens to make claims to social rights. But the tutela came to serve that purpose to the extent that hundreds of thousands of such claims occur each year in Colombia, while the direct access petition is rarely used or accepted in South Africa. The starting point or institutional design does not in itself determine the future shape or scope of these mechanisms. The emergence of a particular kind of constitutional vision can prompt judges, lawyers, and societal actors to expand or contract their expectations and behaviors, pushing legal mechanisms beyond their original purview (as was the case in Colombia) or limiting them after the fact (as was the case in South Africa).

The embedding process can unfold in unexpected and uncontrolled ways. No single actor holds the reins. Even the most charismatic jurist cannot determine the extent of legal embedding or the contours of the constitutional vision that becomes embedded. The same applies to social embedding. In the messiness of social, political, and legal interaction, what emerged in South Africa is the legal embedding of social constitutionalism, undergirded by a somewhat deferential view on the relationship between the courts and the other branches of government (what Fowkes (Reference Fowkes2016) describes as a “constitution-building approach”), without social embedding, as evidenced by the combination of limited knowledge about the Constitution and skepticism about the efficacy of constitutional rights on the part of everyday South Africans. Does this mean the constitutional experiment failed? No, not at all. Instead, what I suggest is that the constitutional embedding process in South Africa is far less deep or stable than what we observe in Colombia. Legal claim-making, as a result, plays a more limited role in the pursuit of constitutional rights promises than might otherwise be the case, and most citizens, in practice, have one less mechanism available for rights redressal.

What has been the impact of the partial embedding of the 1996 Constitution? On the one hand, social constitutionalism has become embedded within the South African legal community. The South African Constitutional Court has developed a set of rules and procedures that set out the parameters of social rights protections. These rules and procedures, such as the requirement of “meaningful engagement” in eviction processes, are tangible to judges and lawyers alike. On the other hand, social embedding seems to be lagging. A “support structure” of NGOs and pro bono litigators helps to push social rights litigation, but buy-in from everyday South Africans has not followed. Thus, we see continued legal mobilization around certain issues, such as potential evictions (in part because of the requirement that evictions be preceded by a court order), but a lack of cases and demand-side pressure to fuel the kind of expansion we saw in Colombia. Legal mobilization is partially pushed forward by legal embedding, but it is not secured by social embedding.

This limited legal mobilization has yielded vitally consequential changes to the rules regarding eviction procedures, the rollout of anti-retroviral medications, and a variety of other issues (Heywood Reference Heywood2009; Budlender et al. Reference Budlender, Marcus and Ferreira2014; Langford Reference Langford, Langford, Cousins, Dugard and Madlingozi2014). These are important advances that have made a real difference in the lives of South Africans. It is hard to imagine that these advances would have resulted from executive action or legislative debate in the absence of this litigation. But if the measuring stick is instead the number of folks living in inadequate housing or without access to other social goods, the picture is less rosy. As of 2015, over thirty million people lived below the poverty line, compared to about twenty-four million at the end of apartheid – in terms of the percentage of the total population, this means 55 percent in 2015 compared to 57 percent in 1996 (HSRC 2004; Statistics SA 2017). The appropriate standard is perhaps up for debate. We can confidently say, however, that the limits of legal claim-making for social rights have not been tested in South Africa, in part because the 1996 Constitution has only been partially embedded.

9.5 Conclusion

This chapter detailed the processes by which the 1996 South African Constitution was firmly legally embedded, particularly at the level of the Constitutional Court, but not significantly socially embedded. Justices of the Constitutional Court and their clerks, who would go on to work at prominent law firms, NGOs, and law schools, embraced social constitutionalism. They were especially receptive to housing rights cases, as they came across housing rights issues in both their daily and professional lives and viewed these issues as conflicting with their sense of contemporary sociolegal values, especially human dignity. Overall, this new constitutional vision included the courts as partners with the executive and legislative branches of government, following what Fowkes (Reference Fowkes2016) calls a “constitution-building” approach. These judges, clerks, and practicing lawyers developed a substantive set of rules of engagement with respect to social rights cases and a particularly robust jurisprudence around issues related to potential evictions.

The relative dearth of social embedding was not for lack of trying. The South African government, like the Colombian government, put together informational campaigns both before and after the new constitutions went into effect. They sought to use popular media to spread knowledge about rights and the possibility to claim rights before the courts. This knowledge did not stick or further spread in South Africa, at least not outside of NGOs and a few social movements. I argue that robust social embedding did not occur – despite substantial opportunities for exposure to the new constitution – because frequent legal mobilization did not occur. While important legal advances have been made in South Africa that have impacted policies and livelihoods, individuals have not been nearly as involved in legal claim-making as in Colombia, with hundreds of thousands of tutela claims being filed and debated every year. Without this kind of legal mobilization to reinforce early exposure to the new constitution and new rights regime, the social element of constitutional embedding lagged. Partial embedding has meant a more circumscribed role for the 1996 South African Constitution than that of the 1991 Colombian Constitution in most people’s daily lives.