Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Conceptualizing Space and Place: Houses, Landscapes, Territory

- Part II Close Readings of Space and Place

- 8 Spaces of Utopia and Spaces of Actuality in Alice Munro's “Jakarta”

- 9 Spatial Perspectives in Alice Munro's “Passion”

- 10 Charting Alice Munro's Terra Incognita: Punctuated Space in “Free Radicals”

- 11 Heterotopy in Alice Munro's “In Sight of the Lake”

- Bibliography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

8 - Spaces of Utopia and Spaces of Actuality in Alice Munro's “Jakarta”

from Part II - Close Readings of Space and Place

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 August 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Conceptualizing Space and Place: Houses, Landscapes, Territory

- Part II Close Readings of Space and Place

- 8 Spaces of Utopia and Spaces of Actuality in Alice Munro's “Jakarta”

- 9 Spatial Perspectives in Alice Munro's “Passion”

- 10 Charting Alice Munro's Terra Incognita: Punctuated Space in “Free Radicals”

- 11 Heterotopy in Alice Munro's “In Sight of the Lake”

- Bibliography

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

IN THIS ESSAY I FOCUS ON the verbalization of space in “Jakarta,” Alice Munro's short story published in the 1998 collection The Love of a Good Woman, with particular reference to the description of women's individual and sociopolitical spaces. The study of space is a way into Munro's redefinition of political utopia as imagined in the 1950s by a woman who rejects the patriarchal world, which tended to enclose women within an actual physical space and, conversely, enlarge ad libitum the masculine sphere of life possibilities. The view of space envisioned in the story is rather postwestern than indigenist or nation-specific. While in part 2 of “Jakarta” Munro accounts for the casualties and shortcomings of the utopian radicalism of the late 1950s, when the West made the first postwar attempt to revolutionize its destiny, in the last section of the tale she eventually outlines an open-ended counterstory of unprogrammable spaces and fields of agency not yet exhausted by accretion and use. As is typical of Munro's fiction, geographical, mental, and social spaces are here used for exploring multiple “identities always in process.” Space thus becomes a storyteller and characters in the story the colporters of their personal and cultural history from late 1950s radicalism to post-ideological disillusionment, and, subsequently, to postwestern utopia located in a Jakarta of imagination.

The story is subdivided into four parts, in which space is organized according to an abab pattern, that is, in a manner corresponding to the rhetorical figure of symploce. The first and third parts are set on the beach of Marine Drive on an island near Vancouver, the second and fourth ones in a cottage in Oregon. The action in Canada takes place in the late 1950s, while in Oregon it shifts to several decades later. In the Canadian section of the story the four protagonists—Kent and Kath, Sonje and Cottar— form two youngish couples; in the more recent sections only elderly Kent and Sonje reappear in the story.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

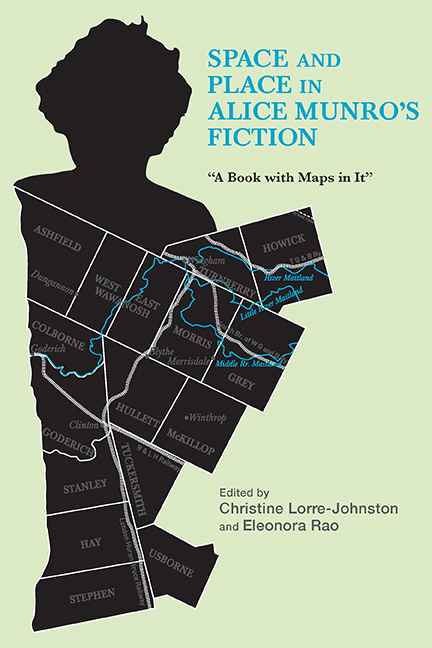

- Space and Place in Alice Munro's Fiction“A Book with Maps in It”, pp. 159 - 170Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2018