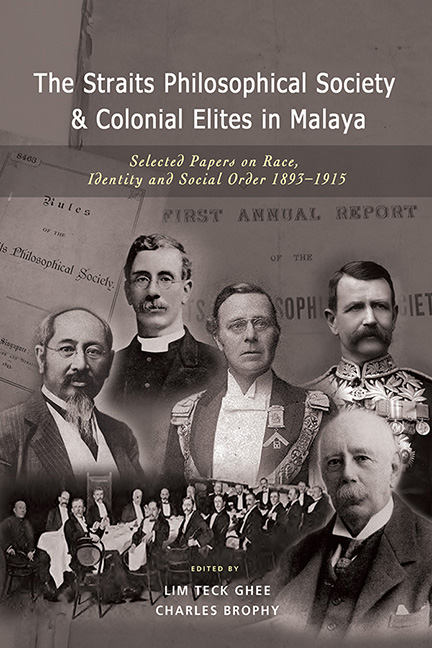

The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in Malaya

The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in Malaya 12 - The Prevention and Repression of Crime

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 January 2024

Summary

Editors’ Note

C.W.S. Kynnersley joined the Straits Settlements Civil Service in 1872, before becoming Superintendent of Prisons in Penang in 1877 and later served as a Magistrate in Penang. According to Ridley in Noctes Orientales his paper of 1893 was one of the few contributions to the Society to affect a policy change in the colony. As with earlier essays on sex work and opium, Kynnersley’s contribution placed emphasis on the Chinese population of the colony, who formed the bulk of the prison population, and who he saw as vital to study in order to understand the roots of crime in the colony. For Kynnersley, the realities of migration and the lack of traditional authority were central themes. In China the Chinese were “under restraint, like a child reverencing his elders and betters”, in Singapore they had no respect for European officials. In such a racialized context Kynnersley would reject liberal opinion in England which saw education as preventative of crime. Instead, he argued that what Singapore required was a better policing and penal system. At the same time he noted that the system’s focus on hard labour tended to produce only hardened prisoners and ignored the potential for their reform and improvement through work.

Tan Teck Soon’s contribution provided a counterpoint. Drawing on the discourse of moral reform in the colony he argued that a proper channel of communication between the Chinese and the authorities would make possible the use of education as a means to teach people the benefits and advantages of upholding the law. This was more than just a question of moral reform for Tan. For him, the Chinese were no longer just temporary migrants but had increasingly made Malaya their home, and the colonial government had an obligation to develop a civic basis for order in the colony. As one of the two Chinese members in the Society, it has been noted that Tan’s notable contribution, as an intellect and writer, was in reconceptualizing Chinese civilization as progressive and open to change, which challenged the prevailing Western idea that Chinese civilization was antiquated and unprogressive.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Straits Philosophical Society and Colonial Elites in MalayaSelected Papers on Race, Identity and Social Order 1893-1915, pp. 159 - 187Publisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2023