9.1 Introduction

How a country chooses to finance health care for its people is an important indicator of the value it places on health as a public good. A country that relies predominantly on public funding for health care reveals a strong commitment by the state to ensure its people’s access to care.1 The growth of private funding for health care, particularly when it results in out-of-pocket payments (OOPPs)2 for households, is a real risk for financial impoverishment.

A country’s history plays a major role in shaping its health system (Reference PhuaPhua, 1989). Some former British colonies in Asia, for example, have retained many welfare-oriented features of the British National Health Service. These include minimal user fees or even free services at the point of use. However, history cannot be the sole reason for current systemic failures in health. Health systems do not remain static but evolve in response to challenges to their resilience. The state is beholden to ensure through good governance that such transformations meet the changing health needs of its people.

What, then, is the situation in Malaysia? Reliable historical estimates of national health expenditure are not fully available. However, it is known that although health care in the country has been mainly financed using public funds since 1997, the share of public funding just barely exceeded that of private funds for health (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2019, p. 26). This is in contrast to the situation in 1983, just slightly more than a decade earlier, when the share of public funding was more than 75% of the country’s health expenditure (Westinghouse Health Systems, 1985, p. 4).

By 1997, not only had private funding of health care reached almost half of the country’s health expenditure, this private funding was also mainly composed of OOPPs (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2019, p. 40). Coincidentally, the 1980s also marked the start of the period when the private provision of health care in the country began a rapid upward trajectory (Reference Chee, Barraclough, Chee and BarracloughChee & Barraclough, 2007, p. 23). Malaysia’s current hybrid health system is one in which the financing and delivery of health care follow the public–private divide – publicly funded public health care providers exist alongside privately funded private health care providers. Over the past few decades, the private health system has expanded at a faster rate than its public counterpart, with consequences not just on the trends but also on the composition of health financing in the country.

However, the raison d’être of any country’s health financing system is not merely to pay for health care. The system should also ensure that the burden of payment, independent of use, is fairly distributed among the population in a country. In many welfare-oriented countries like Malaysia, this translates to a progressive health payment system where richer households contribute proportionately more from their income than poorer ones (Reference Yu, Whynes and SachYu et al., 2008). In addition, the system should also ensure that health funds, especially public funds, are allocated in a manner that can meet population health needs. Like many other middle-income countries, Malaysia is undergoing an epidemiological transition from communicable to non-communicable diseases (NCDs). To curtail the epidemic of these chronic lifestyle diseases effectively, adequate funding should be allocated to preventive and promotional services, early disease identification, early treatment initiation and, most importantly, sustained delivery of needed care. In the case of NCDs, most of these services can be provided efficiently at the primary care level.

This chapter will tell the story of Malaysia’s changing health financing landscape. It starts with a description of the trends in health financing since the 1980s; not just overall expenditure figures but also an analysis of the different financing sources that comprise public and private health financing. This section will also include a brief review of allocative efficiencies in terms of spending patterns according to the categories of services. As financing sources are intricately linked to how health care providers are paid in Malaysia, the narrative will also outline a discussion on the changes within the health care delivery system, the forces at work behind these transformations and the eventual impact on health care financing in this country. The chapter will end with a review of the challenges facing health care financing and a discussion of the way forward for Malaysia.

9.2 Trends in Health Care Financing in Malaysia

The work involved in estimating national health expenditure is not only data-intensive but also has to be conducted in a systematic manner following internationally accepted accounting frameworks to facilitate comparability across time and countries. Efforts to develop the Malaysia National Health Accounts (MNHA) (Box 9.1) to routinely capture the totality of financing flows within the Malaysian health system only started in 2001, and to date, MNHA has produced a series of national health expenditure estimates spanning 1997 to 2017 (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2019, p. 24). Despite the lack of such accounting systems in the years prior to this, it is still possible to obtain an understanding of the public–private mix of health financing in the country from government documents and reports.

The Malaysian government disseminates policy directions for national development in a series of reports known as the Malaysia Plans, reviewed and updated every five years. The First Malaysia Plan, covering from 1966 to 1970, focused on national priorities during the early years after the birth of Malaysia, and the country is currently in the Eleventh Malaysia Plan period (2015–2020). These reports detail achievements in various economic or social sectors, including health, in the preceding five years before going on to lay down the government’s policies for the following five years. The reports also detail the financial allocations that the government has committed towards the implementation of the policies. The health chapter contained in the Fifth Malaysia Plan (1986–1990) was pivotal. While the first four reports were essentially a re-telling of government priorities to increase public investment in the public health sector, especially to expand access to rural health services (Malaysia, 1966; 1970; 1976; 1981), the Fifth Malaysia Plan was the first to acknowledge the growing financial burden on the government such that ‘programmes for health services under the Fifth Plan will take into account the limited financial capacity of the public sector as well as the need to expand the health care system’, and it noted the need to seek out new sources of health financing, including increased cost sharing with the community to ensure that ‘those who can afford to pay bear a larger share of the cost burden’ (Malaysia, 1986, p. 514).

The Malaysian government collaborated with the United Nations Development Programme in 2001 to initiate the MNHA Project (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2006, p. ii). The MNHA Project was eventually institutionalised within the Ministry of Health (MoH) as the MNHA Unit in 2005 (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2008, p. 1).

The estimation framework adopted by the MNHA was based on the System of National Accounts developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, which allowed for the systematic capture of health expenditure data from multiple sources and the reporting of a rich array of expenditure information along three dimensions, namely financing sources, health providers and health care functions (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2006). Essentially, the MNHA information system permits the tracking of health funds from the funding source to the health care provider and finally to the purpose for which the health funds have been used.

It was apparent that concerns over the government’s ability to sustain public funding of health care using revenues from general taxation grew in the period of the Fourth Plan. This led the government to initiate the Health Services Financing Study (HSFS)3 in 1983 to review the performance of the overall Malaysian health system and to provide recommendations for alternative financing methods for Malaysia (Westinghouse Health Systems, 1985, pp. 1–10). As part of the work, the HSFS estimated that, in 1983, Malaysia spent $1.8 billion4 or 2.8% of the gross national product (GNP) on health (Westinghouse Health Systems, 1985, p. 165). The HSFS noted that 76.6% of this amount was spent on public health care services delivery and that these funds came mainly from general taxation. Full understanding of the estimated private sector expenditure has been difficult, as a full description of the funding sources was not provided. However, the report noted a ‘direct payments’5 component that may refer to OOPPs in households (Westinghouse Health Systems, 1985, p. 165). The OOPPs for households in 1983 was estimated at 18.8% or nearly a fifth of the entire country’s health expenditure.

In his classic review of the Malaysian health system of 1984, Reference RoemerRoemer (1991, pp. 395–412) also included an estimate of Malaysia’s health expenditure. He had gathered the available information about the country’s health expenditure from various sources and concluded that the country’s health expenditure in 1983 totalled $1.7 billion, or 2.6% of the GNP, of which 74.3% was from public sources and 25.7% was spent on purchases of care from private providers (Reference RoemerRoemer, 1991, p. 408). He was unable to provide an estimate of OOPPs.

Thus, although comprehensive estimates of Malaysia’s national health expenditure in the early years are scarce, both the HSFS’s and Roemer’s accounts appear to concur in that, at least in 1983, about three-quarters of the health funding in Malaysia came from public sources and that possibly nearly a fifth of health funding in the country had come from private household OOPPs.

The MNHA yielded more contemporary estimates. The available information showed that total expenditure on health (TEH) in Malaysia increased more than three-fold in real terms from Malaysian ringgit (RM) 17.1 billion to RM 57.4 billion over the 21 years from 1997 to 20176 (Table 9.1). However, this increase is less apparent after taking into consideration population expansion over this period. The increase in health expenditure per person was just two-fold – from RM 790 in 1997 to RM 1,790 in 2017. During this time, health expenditure as share of gross domestic product (GDP) had fluctuated within a narrow range, from a low of 3.0% in 1997 to a high of 4.3% in 2015.

| Year | TEH1 (billion RM in 2017 prices) | Per capita TEH1 (RM in 2017 prices) | TEH as % GDP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | 17.10 | 790.09 | 3.03 |

| 1998 | 16.88 | 755.86 | 3.23 |

| 1999 | 18.34 | 799.74 | 3.31 |

| 2000 | 19.88 | 846.41 | 3.30 |

| 2001 | 21.85 | 906.45 | 3.60 |

| 2002 | 22.75 | 920.65 | 3.56 |

| 2003 | 27.78 | 1,096.30 | 4.11 |

| 2004 | 27.72 | 1,070.70 | 3.84 |

| 2005 | 25.50 | 963.95 | 3.35 |

| 2006 | 29.70 | 1,107.35 | 3.70 |

| 2007 | 31.32 | 1,152.02 | 3.67 |

| 2008 | 32.26 | 1,171.44 | 3.61 |

| 2009 | 36.30 | 1,301.74 | 4.12 |

| 2010 | 37.89 | 1,325.34 | 4.00 |

| 2011 | 39.29 | 1,352.41 | 3.94 |

| 2012 | 42.76 | 1,449.43 | 4.07 |

| 2013 | 44.98 | 1,489.05 | 4.09 |

| 2014 | 49.38 | 1,608.21 | 4.23 |

| 2015 | 53.11 | 1,703.04 | 4.33 |

| 2016 | 54.00 | 1,706.76 | 4.23 |

| 2017 | 57.36 | 1,790.00 | 4.24 |

1 Total expenditure on health. TEH and per capita TEH are reported in RM in 2017 prices.

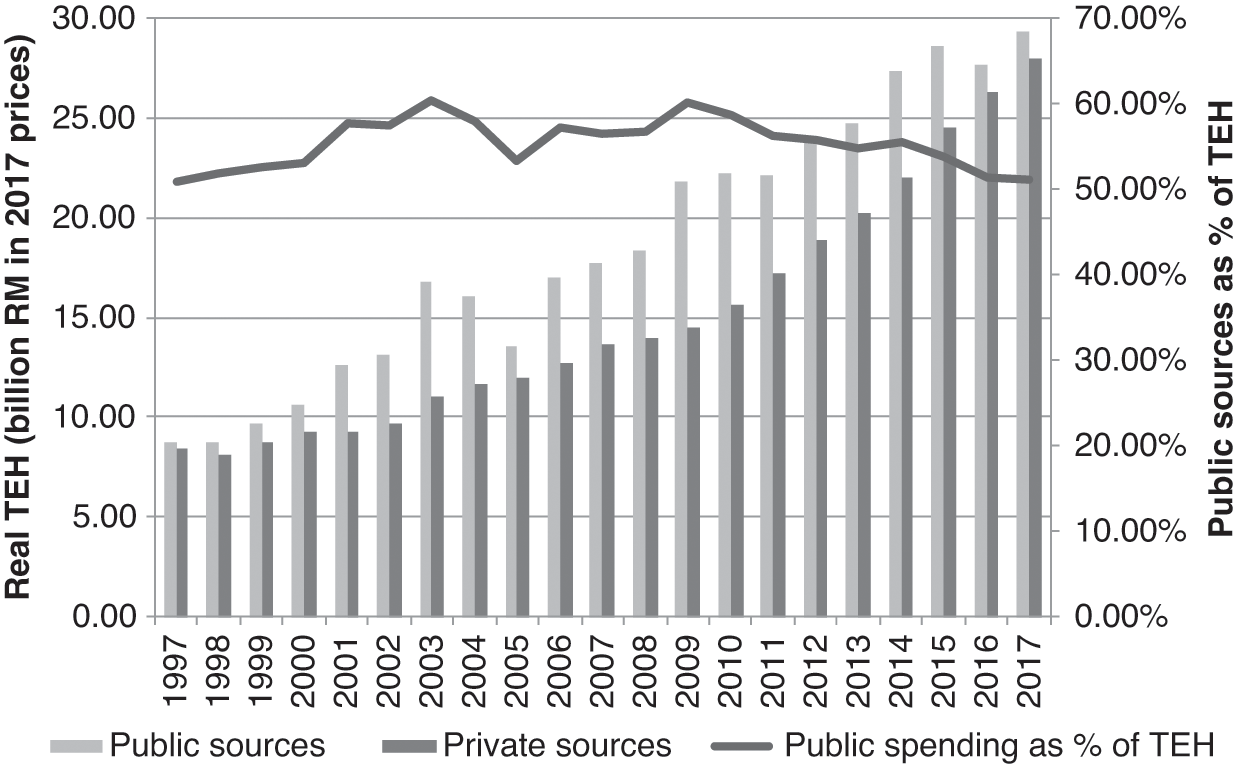

Public funding of health care predominated throughout 1997 to 2017, but public shares did not exceed 61% of TEH (Figure 9.1).

The MNHA categorises sources of health expenditure by the institutions directly incurring expenditure on health care, with the understanding that these institutions can control and finance such expenditure (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2006, pp. 14–15). Financing sources are then further divided into public and private sources (Box 9.2).

The public sources of health care financing are mainly government agencies at the federal, state or local authority levels, as well as social security agencies in Malaysia. These include:

– The MoH as the main provider of health care in the country.

– The Ministry of Education with its teaching hospitals.

– The Ministry of Defence with its health facilities for providing care mainly to military personnel and their dependents.

– State and local authorities providing services mainly related to sanitation, food quality control and vector control services in larger towns.

– The EPF, a fund providing retirement benefits for its members that also permits withdrawals for members’ health care needs.

– The SOCSO, a workers’ compensation scheme that provides financial benefits when workers suffer disabilities due to work-related injuries and illnesses.

The main private sources of health care financing are:

– Private health insurers that pay health care providers for the care consumed by those insured under their programmes.

– MCOs, which are not risk takers but function mainly to administer the health benefits of those who are enrolled in their health schemes. These companies purchase third-party insurance coverage, which is then bundled into the health schemes they sell to individuals as well as to companies.

– Private corporations that pay for the health care consumed by their employees as part of their employment benefit plans.

– Private household OOPPs for health, which refers to the portion of health care payments not paid for by any third-party payers and which are thus borne directly by households.

Most of the public funding for health comes from government agencies, to which the MoH contributed the largest share – exceeding 80% of the total public funding of health annually (Table 9.2). Among the public sources of health financing, the two main social security organisations in Malaysia, the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) and the Social Security Organisation (SOCSO), are minor contributors. Although these organisations do incur health expenditures because they finance some health care for their members, health care is not the primary component of their benefit packages. Consequently, health funds from these organisations do not feature prominently in the estimates of TEH in Malaysia. In 2017, the combined health funding from the EPF and SOCSO amounted to only 0.7% of TEH or 1.3% of financing from public sources (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2019, p. 30). In 1997 – 2017, on average, the annual social security contributions to TEH accounted for only 1.2% of overall public funding.

| Year | Public sources of financing in billion RM1 (% of TEH) | Private sources of financing in billion RM1 (% of TEH) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoH | Other government agencies2 | Social security3 | Private insurance | OOPPs | Private corporations | Other4 | |

| 1997 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1998 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1999 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2002 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2003 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2004 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2005 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2006 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2007 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2008 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2011 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2014 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2016 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 2017 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Over the years, funds from private health insurers have gradually increased, reflecting the uptake of private health insurance in Malaysia. In 2005, about 15% of the population had some form of health insurance cover (Central Bank of Malaysia, 2005, p. 58). By 2014, the coverage had increased three-fold to 45% of the population, or about 14.7 million people (Malaysian Productivity Corporation, 2016, p. 112).7 In 1997, private health insurers financed 4.0% of the nation’s TEH, and this share increased to 8.8% in 2017 (Table 9.2). In contrast, the financing component from private corporations dropped from 7.2% of total health financing in 1997 to 2.3% in 2017, perhaps as a result of corporations purchasing third-party health insurance cover for their employees instead of self-insurance or obtaining the services of managed care organisations (MCOs). The predominant private financing source in Malaysia from 1997 to 2017 remained private household OOPPs, which made up on average 74.7% of the annual private health expenditure or 37.6% of the annual TEH in Malaysia. In fact, private household OOPPs is one of the main financing sources for health care in Malaysia, second only to the MoH (Table 9.2).

From the perspective of household welfare, private funding of health care is not desirable. Services provided by government agencies, including the MoH, are mainly funded through general taxation (Reference Rozita and SararaksRozita, 2000). As in most countries, taxation in Malaysia has been structured to ensure that the wealthy are required to pay more in taxes as a proportion of their income than the poor. The progressive nature of taxes in Malaysia is reflected in the funding of health care partially from general taxation (Reference Yu, Whynes and SachYu et al., 2008). Regardless of contribution, entitlement to care remains the same. This makes for a fairer distribution of the burden of health funding. In addition, this form of public funding has several welfare-enhancing features, including fund pooling and pre-payment (Box 9.3), which protects households from financial catastrophe resulting from health payments.

Are these lauded pre-payment and fund pooling features absent in private funding sources? Not quite, as these features are also present, albeit to a limited extent, in some private funding sources, including private health insurance and private corporations. However, the financial risk protection these mechanisms confer is restricted to those who have bought private insurance cover or those with formal employment that provides health benefits. Unfortunately, in the case of Malaysia, funding of health care from these private sources pales in comparison to private household OOPPs for health care, a financing source that has neither pre-payment nor fund pooling features (World Health Organization, 2010, pp. 5–6).

Pre-payment for health care describes a situation in which payment for health care is made in advance of the need for care. As a person’s health, and thus their need for health care, is uncertain (Reference ArrowArrow, 1963), it would be difficult for anyone to have enough savings to cover all health care eventualities. Pre-payment circumvents this problem by ensuring that care is paid for in advance and will be made available when needed.

Fund pooling refers to the pooling of collected health funds before payments are made to providers (World Health Organization, 2010, p. 4). This is intended to distribute the financial risks of ill health among a pool of people. Once a person contributes to the pooled funds, they are entitled to health care paid for from the pool. However, restrictions may apply to such payments and may be related to the types of services to be funded, levels of co-payments and other financial limits.

Private household OOPPs for health care is the one source of health financing with the highest potential to impact household welfare adversely, especially for poorer households (World Health Organization, 2010, p. 5). A multi-country assessment has shown that household financial catastrophe caused by OOPPs for health care can only drop below negligible levels if that country’s OOPPs are below 15–20% of TEH (Reference Xu, Saksena, Jowett, Indikadahena, Kutzin and EvansXu et al., 2010). In 1997 to 2017, during which health expenditure has been reliably estimated, the levels of OOPPs for health in Malaysia have consistently exceeded this threshold (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2019, p. 24). Despite this, the levels of financial catastrophe arising from health care payments in Malaysia have been surprisingly low. In 1998, when OOPPs for health made up 35.7% of TEH, only 0.8% of households paid OOPPs for health care exceeding 25% of their non-food expenditures (Reference van Doorslaer, O’Donnell, Rannan-Eliya, Somanathan, Adhikari and Gargvan Doorslaer et al., 2007).

These large OOPPs were concentrated in the richer households. In 2009, OOPPs made by only 0.2% of households in the poorest quintile exceeded the 25% of non-food expenditure threshold as compared to 0.55% of households in the richest quintile (Health Policy Research Associates et al., 2013, p. 37). Thus the situation in Malaysia appears to defy the conventional wisdom that high levels of OOPPs for health in a country lead to high levels of household financial catastrophe (Box 9.4).

The observation that high OOPPs in Malaysia have not appeared to create household financial catastrophe or differences in utilisation across income is surprising and points towards the importance of checking intuition with data and disaggregating populations when attempting to model health systems. While this finding is welcome, it should not be assumed that this state of affairs will automatically persist if current arrangements between the public and private sectors remain the same. Indeed, systems often have both zones of stability and tipping points outside of these zones, where change can be swift and dramatic. As such, continued close monitoring of public and private health care spending and the development of causal models that predict impact on household financial security are important.

The explanation may lie in the fact that, for most households in the country, health care remains affordable. In 2009, on average, OOPPs for health made up only 1.1% of the average household expenditures, with the poorest quintile of households committing only 0.7% of household expenditures to pay for health care and the richest households a 1.5% share (Health Policy Research Associates et al., 2013, p. 32). The situation in Malaysia supports the findings from recent international comparative work on financial risk protection for health (Reference Wagstaff, Flores, Hsu, Smitz, Chepynoga and BusmamWagstaff et al., 2018a; Reference Wagstaff, Flores, Hsu, Smitz, Chepynoga and Busmam2018b). These studies suggest that the levels of financial risk protection offered to the population may not depend on health expenditure as share of a country’s GDP but on shares of TEH that are pre-paid, especially through taxes and other mandatory contributions. In 2009, pre-paid sources of financing8 made up 69.7% of TEH, with government agencies funding up to 59.7% of TEH, most of which came from taxation (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2019, p. 25). It would seem that the high levels of pre-payment inherent in the taxation-funded Malaysian health care system have conferred protection against financial catastrophe for most of the population in the country.

Financial risk protection aside, there are arguments to suggest that health care resources in Malaysia may not have been allocated in a manner that yields maximum health benefits (Ministry of Health Malaysia & Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, 2016, pp. 87–91). Partially due to lifestyle changes in the Malaysian population, NCDs are emerging as a major health issue in the country. In 2015, the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes among the adult population in Malaysia was 30.3% and 17.5%, respectively (Institute for Public Health, 2015, p. 22). More alarmingly, about half of the adults with these conditions were unaware of them and thus did not seek treatment. NCDs such as hypertension and diabetes should be identified and managed in a primary care setting (Reference Varghese, Nongkynrih, Onakpoya, McCall, Barkley and CollinsVarghese et al., 2019). However, the strength of Malaysia’s well-established public primary care delivery system lies mainly in the provision of acute care services related to communicable diseases, minor ailments and maternal care (Reference Mustapha, Omar, Mihat, Noh, Hassan and BakarMustapha et al., 2014). Some re-orientation of thinking would be required for the expansion to the country’s primary care system to manage the increasing burden of chronic NCDs effectively.

Strengthening the primary care system in Malaysia would require substantial financial investment. However, the patterns in TEH show otherwise. It has been estimated that Malaysia spent 49% of TEH on secondary and tertiary care and only 17% on primary care (Ministry of Health Malaysia & Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, 2016, p. 87). The pattern of government spending was even more skewed, with only 11% of the expenditure allocated to primary care as opposed to 65% to secondary and tertiary care services. However, more disconcerting is that shares of health expenditure for primary care services declined from 13% in 2008 to 10% in 2010.

This brief review of the available national expenditure for health appears to indicate the increasing prominence of private funding of health care, particularly the OOPPs component, in Malaysia. Malaysia’s situation is different from that of many other countries, such as South Korea, Taiwan and Japan, where public funds are used to pay private health care providers. In this country, public funding is mainly channelled to the public health system; likewise, private sources fund the private health sector. Thus the rise of private health funding in Malaysia is likely to be mirrored by a similar rise in private provision of health care.

9.3 The Expansion of the Private Health Sector in Malaysia and Its Impact on Health Care Financing

Public and private provision of health care have long co-existed in Malaysia. However, the size of these two sectors, as well as the composition of health care providers, have changed over the years.

In the early days, private health care providers did not feature prominently in the health landscape and consisted mainly of single-doctor clinics in the larger towns. Reference RoemerRoemer (1991, pp. 402–4) noted that in 1984, the public health care system, of which MoH facilities made up the largest component, was the backbone of health care delivery in the country in terms of geographic coverage and health infrastructure. However, rapid development of the private health sector started in the 1980s, and this was more apparent in the hospital sector (Reference CheeChee, 2008). In 1980, there were only 50 private hospitals with 1,171 beds, or 5.8% of all acute hospital beds in the country (Reference CheeChee, 2008). Over the next 5 years, the number of private hospitals more than doubled to 133 with 3,666 beds, or 14.5% of the country’s acute hospital beds. Since then, the capacity of private hospitals has continued to increase at a faster pace than that of public hospitals such that by 2017, the share of private hospital beds had increased to 27.3% of all acute hospital beds in the country (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2018a). In the same year, approximately 30% of all acute hospital admissions were in private hospitals (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2018a).

Growth of the private health sector was not just evident from the numbers of hospital beds alone but also from the diversity of health care facilities in the country. The MoH is the main regulator of the private health sector. Prior to 1998, the ministry regulated only three categories of private health facilities: hospitals, maternity homes and nursing homes. Since then, this list has expanded to include psychiatric hospitals, ambulatory care centres, psychiatric nursing homes, blood banks, haemodialysis centres, hospices, community mental health centres and medical and dental clinics. The MoH currently regulates a total of 12 distinct categories of private health care facilities in Malaysia (Table 9.3).

| Facility | 2007 | 2010 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical clinic | 2,992 | 6,442 | 7,571 |

| Dental clinic | 937 | 1,512 | 2,137 |

| Hospital (beds) | 195 (11,291) | 217 (13,186) | 200 (14,799) |

| Maternity home (beds) | 21 (175) | 22 (97) | 16 (50) |

| Nursing home (beds) | 10 (228) | 12 (263) | 22 (700) |

| Hospice (beds) | 3 (28) | 3 (30) | 2 (17) |

| Ambulatory care centre (beds) | n.a. | 36 (125) | 100 (186) |

| Blood bank | n.a. | 5 | 4 |

| Haemodialysis centre (chairs) | n.a. | 191 (2,195) | 450 (484) |

| Community mental health centre (beds) | n.a. | 1 | 1 |

| Combined ambulatory care centre and haemodialysis centre (beds/chairs) | – | – | 1 (14/21) |

n.a. – not available

The expansion of the private health sector in Malaysia has had a direct impact on the public–private mix in health financing. The provision of public health care is mainly financed by general taxation. Other minor funding sources for public health care are private household OOPPs, employer-sponsored care, private health insurance and EPF and SOCSO. In 2017, 97.6% of funding received by MoH hospitals came from general taxation, 1.9% was from OOPPs, 0.3% was private health insurers and 0.2% was from EPF and SOCSO (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2019, p. 78). The main reason these sources play a much less significant role in financing public health care is because public funds from taxation have been used to keep user fees9 low for most services provided in public health facilities (Reference RohaizatRohaizat, 2004). The government legislates user fees for MoH facilities (Reference Ng, Barber, Lorenzoni and OngNg, 2019). Although these fees are meant as a tool for cost recovery in public health facilities (Malaysia, 1990, p. 353), they are much lower than the actual cost of delivering the services. It was estimated that the cost of an outpatient visit to a MoH hospital in 2009 ranged from RM 77.46 to RM 129.11 (Institute for Health Systems Research, 2013, p. 6). The comparable legislated fees for the first specialist outpatient visit to a MoH hospital would have been RM 30.00 if the patient had been referred by a private clinic and free if the referral had come from a public clinic (Government of Malaysia, 1982). The fees for subsequent visits were RM 5.00 for each visit. In 2014, medical fees billed to patients amounted to only 1.4% of the ministry’s operating expenditure (Ministry of Health Malaysia, 2015, pp. 32–6). The shortfall was made up using general taxation.

In contrast to the public sector, private health care providers do not receive direct government funding to provide health care services to the public. In consequence, fees in the private sector are set at cost plus profits and are thus higher than those in the public sector. As a measure to ensure that such services remain affordable, the government regulates professional medical fees charged by doctors practising in private facilities (Government of Malaysia, 1998).10 In 2013, a patient would have had to pay RM 80 to RM 235 for the first specialist outpatient visit to a private hospital and RM 40 to RM 105 for subsequent visits (Government of Malaysia, 2013). This excludes fees for drugs, investigations and other administrative charges. In 2012, the average household monthly income per person was RM 1,451 (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2013, p. 12). Payment of fees for private health care services comes from a variety of sources. As part of their employment benefit packages, employees’ health care may be paid in full or partially by employers. The health care for persons who have purchased private health insurance may be paid in full or partially by their health insurers. Some EPF members may also withdraw funds to pay for health care. Unlike the public health sector, which receives the bulk of its funding from general taxation, the major funding source for private care is private household OOPPs.

Changing consumer preferences could have accounted for the changes in the public–private mix of health care providers. Over time, increasing consumer purchasing power has allowed at least the rich to purchase the more expensive, yet at the same time perceived to be of higher quality, private care (Reference Chee, Barraclough, Chee and BarracloughChee & Barraclough, 2007). However, the expansion of the private health sector in the 1980s could also be partially attributed to enabling government policies that encouraged private sector participation in all sectors of the Malaysian economy, including the health sector. The British welfare philosophy on health care, which emphasised public provision and funding of care for all, had guided the early development of the health sector in this country (Reference BarracloughBarraclough, 1999; Reference Chee, Barraclough, Chee and BarracloughChee & Barraclough, 2007; Reference Rasiah, Wan Abdullah and TuminRasiah et al., 2011). Mirroring developments in the United Kingdom itself, where government commitment to these noble sentiments has also been watered down over time, the Malaysian government has gradually changed its stance on public provision and financing of health care to meet the health needs of the country.

In 1983, the government unveiled its privatisation policy to actively increase private sector participation in the development of the country’s economy (Institut Tadbiran Awam Negara Malaysia, 1994, pp. 62–3). This move was aimed at reducing the presence of the government in the economy and at lowering the level and scope of public spending. In the realm of health care, the government encouraged private provision of care, stating that ‘the private sector, including NGOs, will be encouraged to expand and complement the Government’s effort in providing a comprehensive range of health care services for all income groups’ (Malaysia, 1996, p. 549). To aid the public’s ability to purchase expensive private care, the government re-structured the main social security agency for private sector workers, the EPF, in 1994 to allow for a medical savings account mechanism to enable EPF members to withdraw their savings for the purchase of health care (Reference NgNg, 2005). The government also provided tax deductions for medical expenses and for the purchase of private health insurance (Reference Chee, Barraclough, Chee and BarracloughChee & Barraclough, 2007).

The government has not only promoted the development of the private health sector but has also invested in private care. Many private hospitals are fully or partially owned by government-linked companies (GLCs)11 but operate as commercial for-profit enterprises (Reference ChanChan, 2014). These GLCs include IHH Health Care Berhad, a subsidiary of Khazanah Nasional Berhad, the federal government sovereign wealth fund, and KPJ Healthcare Berhad, a public-listed company belonging to Johor Corporation, the investment arm of the Johor state government. Other state governments, including those of Terengganu and Malacca, are also involved in providing private health care. Sime Darby, another GLC, owns hospitals through Ramsay Sime Darby, a joint venture with Ramsay Health Limited, an Australian company. Currently, the proportion of private hospital beds owned by GLCs exceeds 50% of the total private hospital beds in the country (Reference Ng, Barber, Lorenzoni and OngNg, 2019). The provision of private health care by GLCs indicates the extent of the reversal in the government’s attitude towards the provision of health care. Early post-independence efforts that focused on expanding publicly funded health care to the whole country, especially the underserved rural areas, which is a welfare-motivated ideal, had by the 1990s given way to the view that private provision of health care could be a socially acceptable manner of distributing health care, especially to the rich, as well as an acceptable manner of generating government revenue.

Towards the end of the 20th century, the government embarked on an additional avenue to support the expansion of private care in the country. Health tourism, the business of providing health care to foreigners, was born in the aftermath of the 1997 Asian financial crisis as an answer to financially ailing private hospitals in the country (Reference CheeChee, 2007). During this time, private hospitals had to turn from the diminishing pool of local patients who were no longer able to afford private care to foreign patients, for whom favourable currency exchange made it financially attractive to enter the country for health care. Initial government support included the MoH setting up the National Committee for the Promotion of Medical and Health Tourism in 1998 to develop strategies to attract foreign patients (Reference CheeChee, 2007). The responsibility of promoting health tourism in the country has now been taken up by the Malaysia Healthcare Travel Council, a public–private collaborative agency housed under the Ministry of Finance (MoF) Malaysia.12 Continued government support of private sector expansion has now been linked to the support for health tourism, as has been made clear in the Eighth Malaysia Plan, which stated that ‘further development of the health sector, particularly tertiary medical care in private hospitals, will provide a conducive environment for the promotion of health tourism’(Malaysia, 2001, p. 495).

The HSFS conducted in 1985 had foreseen that the private health sector in Malaysia was ‘on the verge of dramatic and explosive potential expansion’ (Westinghouse Health Systems, 1985, p. 3), and in a sense this prediction has come true. However, as seen in the above narrative, the expansion of private health care has generally been welcomed. Private provision of care is seen to complement public provision of care. The government stated its intention to reduce its role in the provision of health care services and instead to concentrate efforts on regulating the health sector (Malaysia, 1996, p. 544). Fears were raised that this would lead to a two-tier health system, with public services, which are perceived to provide a lower quality of care in return for lower fees, being relegated to the poor while the rich can afford expensive, higher-quality private care (Reference Ng, Mohd Hairi, Ng, Adeeba, Tey, Cheong and RajahNg et al., 2016, p. 187). To date, the pattern of health care utilisation, especially for inpatient care, does not appear to support these sentiments.

In 2011, it was estimated that on average, each person in Malaysia had 4.3 outpatient consultations and that there were 111 inpatient discharges per 1,000 population in the country (Health Policy Research Associates et al., 2013, p. 20). The outpatient consultations were equally distributed between public and private health care providers. However, inpatient admissions were predominantly public. Admissions to public hospitals made up 74% of all admissions. However, it is more interesting to note that there was no income gradient in the utilisation of outpatient and inpatient care services. While outpatient and inpatient utilisation were the same across income quintiles, there was a distinct pro-rich distribution for the use of private health care services and, conversely, a pro-poor distribution for public care (Health Policy Research Associates et al., 2013, pp. 55–6).

To increase the accessibility of private care, the government has repeatedly announced its intention to reform the country’s health care financing system to provide ‘consumers with a wider choice in the purchase of health services from both the public and private sectors’ (Malaysia, 2001, p. 495). The financing mechanism that has garnered the most attention thus far has been that of social health insurance (Reference Tangcharoensathien, Patcharanarumol, Ir, Aljunid, Mukti and AkkhavongTangcharoensathien et al., 2011).

Social health insurance is seen as an appropriate replacement for general taxation-financed health care, as both public funding sources, with their pre-payment and fund pooling features, can provide financial risk protection to the public. This remains an important policy consideration in the welfare-conscious governance of the country. To date, there have been no major reforms to the country’s financing system. However, various agencies, including the MoH, have made preparations for the yet-to-happen change, in the absence of which, some of these changes have been diverted to other uses. Changing the way health care is financed in Malaysia from general taxation to social health insurance is a major endeavour that would require a major change in the mindset of health managers. As shown in Case Study 9.1, resistance to change within the public sector can impede the adoption of newer and more efficient accounting systems.

The separate financing and health care delivery systems in Malaysia do not just shape equity of health and financial outcomes. As described within this chapter and elsewhere in this book, this structure has shaped how the health system functions as a whole. Because of the movement of patients and health workforce between the public and private health systems in Malaysia, decisions on financing policies should take impacts on both into account even though the policy may, on the surface, only target one or the other

9.4 Conclusions

This short review of the trends in health financing in Malaysia outlines the rise in private funding of health care, especially private household OOPPs, since the 1980s. This trend is related to the expansion of the private provision of care. With few minor exceptions, there is a clear division between public funding for public care and private funding for private care. With this dichotomy in place, the government has found it increasingly difficult to commit sufficient public funds to meet the growing health care needs of the population. Cost sharing, which describes the partial transfer of the health financing burden from public funding to private pockets, entered the government policy lexicon in the 1980s. To enable cost sharing, the government has put in place policies to enhance the growth of the private health sector to encourage the consumption of private care by the segments of the population that can afford to pay, while at the same time, public funds have been committed to support public provision of care.

In 2018, the government announced that it would explore a health care scheme that aims to create a national health financing scheme ‘to provide assistance for primary care treatment for the B4013 households to ensure comprehensive health coverage’ (Malaysia, 2018, pp. 11–20). Under this scheme, referred to as PeKa B40, which has since been rolled out in April 2019, public funding from general taxation would be used to pay for private care for the poor.14 This new development may herald the tearing down of the wall dividing public funding from private provision, leading to more efficient use of health care resources for the benefit of all in Malaysia.

9.5 Key Messages from Malaysia’s Experience

9.5.1 What Went Well and Not So Well?

For the first 45 years, with a relatively young population, it was possible to achieve relatively good outcomes with relatively low health care expenditure.

However, the system needs to adapt to new challenges to continue reaping such benefits (relatively affordable health care).

With a hybrid public–private financing and delivery system:

◦ The public sector, which is welfare-oriented, uses pooled tax funds to provide:

access and financial protection to the poor, and

protection from catastrophic health expenditure for households – a safety net for all sectors of the population.

◦ The private sector initially complemented the public sector by catering for those who could afford it, but it now has an increasing share of OOPP expenditure due to:

low private health insurance uptake, and

fee-for-service provider payment mechanisms.

◦ This threatens social efficiency in the provision of health care.

9.5.2 Trends and Challenges

Health expenditure is likely to rise (due to an ageing population, epidemiology and technology).