2.1 Introduction

In any attempt to “rethink” biodiversity governance, we need to consider that defining nature (and related concepts such as biodiversity, ecosystems, landscapes or green infrastructure) is not merely an objective scientific exercise. In reality, context-specific, subjective, normative and dynamic worldviews and values are at play in any definition of nature, whether explicitly or implicitly. Being aware of this pluralism is essential for avoiding “objective” definitional attitudes that risk disregarding and marginalizing the plurality of values and worldviews connected to different definitions of nature. In fact, paternalistic positions can create breeding grounds for fruitless dialogues between stakeholders, and thus pluralistic approaches help open up spaces for discussion.

In the modern era, Western worldviews have emphasized the separation between culture, humans and nature, dating back to at least the era of the Old Testament. This distinction has come to be known as the nature/culture divide, a dichotomy that posits nature as a separate and discrete object that can be known, conquered and used at will for humankind’s benefit, with consequences beyond theoretical and philosophical discussions (Reference CastreeCastree, 2013). Different interpretations exist on when and how this divide came to be (Reference PattbergPattberg, 2007; Reference UgglaUggla, 2010). In her classic book The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution, Carolyn Reference MerchantMerchant (1980) pointed out how the image of nature as a nurturing mother was gradually transformed during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries into an image of nature as being wild, chaotic and uncontrollable, a position directly related to the dominant view on women at the time and a view that justified the domination of nature and the exploitation of its resources.

The environmental historian Donald Worster has proposed that since the Industrial Revolution, two key threads can be discerned in the way Western societies relate to nature. First, the “imperial” or Linnean tradition emerging from the development of biological classification of species and scientific exploration had the ambition to “establish, through the exercise of reason and by hard work, man’s dominion over nature” (Reference WorsterWorster, 1977: 2). At the same time, the Industrial Revolution led to a second strand that emerged as a countermovement to the idea of human domination, which Worster terms “Arcadian,” and that “advocated a simple, humble life for man with the aim of restoring him to a peaceful coexistence with other organisms,” given the depredations of industrial life (Reference WorsterWorster, 1977: 2). This second strand has taken many different forms over time; for example, in the later nineteenth century, Romanticism, despite being a heterogeneous movement, challenged the idea of human domination over nature and modernity by idealizing wild nature for its beauty and purity (Reference UgglaUggla, 2010).

The nature/culture divide has come under criticism as a cultural construction not universally applicable to the whole of human societies (Reference DescolaDescola, 2013), and as an invalid dichotomy for the West as well (Reference LatourLatour, 1991). These criticisms are not solely theoretical, as they raise the fundamental question “what is nature?” and reject a single objective answer. Thus, nature is a plural concept, and in this chapter we argue that this plurality reflecting the different values of nature will play a fundamental role in transformative biodiversity governance. Yet this does not come easily, as a plurality of values means a plurality of ontologies, epistemologies, interests and needs.

The authors do not pretend to present an exhaustive nature-definition overview in this chapter, nor to be without bias: The content of this chapter largely builds on the expertise and experience of the collaboration between them. And of course, explicitly or implicitly, certain accents or interpretations may come across more strongly than others. Nevertheless, we mainly hope to share with the reader a rich display of definition examples and elements, illustrating the core intention of this chapter: to show that nature is defined, and cannot be taken for granted as one objectifiable concept. After a brief introduction of the concept of biodiversity (Section 2.2) as a root scientific concept for conservation, we provide an overview of some of the ways nature has been defined over time and what this means for biodiversity conservation. Section 2.3 deals with wilderness, intrinsic value and how these are interlinked with protected areas. Section 2.4 addresses the concept of landscape via two lenses: ecosystem services and biocultural diversity. Instrumental and relational values of nature are also discussed. Section 2.5 takes the increasingly popular tool of conferring nature with legal rights (Rights of Nature) as demonstrating hybrid forms of biodiversity governance that attempt to merge Western and non-Western ontologies and definitions of nature. Section 2.6 discusses the importance of scenarios for nature in order to develop alternative pathways grounded on value pluralism. Section 2.7 concludes the chapter by drawing general conclusions for transformative biodiversity governance.

2.2 Nature Defined in the History of “Biodiversity”

Attention to the conservation of nature often manifests as a response to the widespread unsustainable and unethical use of nature (however defined) that stems from a view of nature from an instrumental value perspective, resulting in overlogging, overfishing, large-scale land-use change, etc. The concept of biodiversity emerged from the scientific community and, despite criticisms, represents one of the most common and recognized concepts for scientists and the general public. The term dates back to 1968, when Dasmann used it for the first time in his book A Different Kind of Country (Reference DasmannDasmann, 1968). While concepts of nature and wilderness had been commonly used previously, with this new term, global diversity that had evolved over more than 3.6 billion years was emphasized, as well as the fact that human impact extended beyond just endangered species. As the term began to circulate and become widely used, one of the first uses of the term was “biological diversity” in the United States. The United States historically played an important role in the design of conservation, where it was mentioned in the Global 2000 Report to the president, written by biologist Tom Lovejoy for President Jimmy Carter in 1980 (Reference Lovejoy and BarneyLovejoy, 1980). The popularity enjoyed by the term partly lies in the increasing concern about an accelerating “extinction crisis” (Reference Ehrlich and EhrlichEhrlich and Ehrlich, 1981; Reference MyersMyers, 1979), as well as the fact that it was a useful catch-all representing the need for increased conservation for the underpinnings of life (Heywood, 1995), and the National Forum on BioDiversity in 1985 cemented the idea that the concept was fundamental for shaping conservation policy (Reference WilsonWilson, 1988). In other words, as biologist E. O. Wilson put it, “Biological diversity – ‘biodiversity’ in the new parlance – is the key to the maintenance of the world as we know it” (Reference WilsonWilson, 1992: 15).

Although the last decades saw a surge in the use of the concept of biodiversity in the scientific community and beyond, the term itself is not uncontested. One “formal” definition of biodiversity, adopted by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992, defines it as “variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems” (Article 2) (CBD, 1992). Many have argued, since the emergence of the term, that it still remains vague and imprecise: “the term biodiversity is beginning to fail as a useful catch-all term for the current planetary environmental crisis … ambiguity of meaning has, in my opinion, rendered the concept of biodiversity increasingly useless as a rallying-point by which to focus attention on the current and on-going dramatic changes to the biosphere” (Reference BowmanBowman, 1998: 239).

Further uncertainty emerges from the task of measuring biodiversity (Reference Walpole, Almond and BesançonWalpole et al., 2009). Early discussions about how different dimensions of biodiversity might best be measured included basic species/area ratios, which, as species diversity generally increases from the poles to the equator, led to biodiversity protection efforts centered in the tropics (Reference Harper and HawksworthHarper and Hawksworth, 1994); a focus on rarity and endemism, such as in “biodiversity hotspots” where such endemic species are under particular threat (Reference Myers, Mittermeier, Mittermeier, Da Fonseca and KentMyers et al., 2000); or on taxonomic character differences within populations, indicating genetic richness to be conserved for the sake of future evolution (Reference Humphries, Williams and Vane-WrightHumphries et al., 1995). In practical terms, the idea of sheer species numbers as equivalent to biodiversity has largely predominated (Reference TakacsTakacs, 1996), although it has led some to question “whether it is adequate – or correct – to base the priorities for global biodiversity conservation simply on the quantity of biological diversity, as is often done” (Reference Fjeldsaa and LovettFjeldsa and Lovett, 1997: 319). More recent discussions have focused on questions of “biodiversity intactness,” “biodiversity health,” “species viability,” and, as we note in the next section, ecological functions and services provided by biodiversity (Reference Dinerstein, Joshi and VynneDinerstein et al., 2020; Reference Mace, Barrett and BurgessMace et al., 2018; Reference Schneiders and MüllerSchneiders and Müller, 2017).

As concerns over the ambiguity of the term and how to measure it allude to, there remained no clear consensus on a single standard interpretation of biodiversity for many years. The difficulty of reconciling alternative interpretations has made critical engagement with definitions of biodiversity difficult and contested when the conceptual roots of the term are questioned (see also Reference Sarkar, Garson, Plutynski and SarkarSarkar, 2016). At the same time, biodiversity has entered the public discourse and is commonly used by newspapers and mass media; as a term, it is gaining in popularity (Reference Levé, Colléony and ConversyLevé et al., 2019), although not (yet) as much as climate change (Reference Legagneux, Casajus and CazellesLegagneux et al., 2018).

Despite these debates, the concept of biodiversity has, more than any other concept in the last decades in Western ecological thinking, been a key contribution in shaping the governance of nature conservation. For example, defining the boundaries of what biodiversity is and where it can be found is required for the creation of targets to “halt biodiversity loss” and, more recently, to “bend the curve of biodiversity loss” (Reference Mace, Barrett and BurgessMace et al., 2018). Yet, as we have noted, these targets do not “naturally” and “neutrally” emerge from agreements within the scientific community. On the contrary, they are negotiated and contested, and they lend themselves to alternative conservation strategies and practices (Reference Bhola, Klimmek and KingstonBhola et al., 2021; Reference Immovilli and KokImmovilli and Kok, 2020; Reference Keune, Dendoncker, Jacobs, Dendoncker and KeuneKeune and Dendoncker, 2013). In the next two sections, we discuss possible ways to look at biodiversity governance and further reflect on how these approaches are grounded in different definitions of nature.

2.3 Nature Defined as Wilderness

The concept of wilderness emerged from the US context in the nineteenth century and soon gained momentum in the wider international conservation debate. As European settlers arrived in the Americas, wild nature was considered the enemy, to be replaced with traces of “modern civilization” (Reference NashNash, 1967). Later, this attitude shifted, and wild nature started to be praised as sacred havens that would spare humanity from the unstoppable expansion of modernity; for example, the well-known American writer Henry David Thoreau advocated for wild nature as a space where modern humans’ excesses could be purified and limited. The cerebral and aesthetic values being praised in this context were advocated by upper-middle class and white American men, whose communing with nature conferred intellectual life, arts and letters (Reference McDonaldMcDonald, 2001; Reference NashNash, 1967). In other words, wilderness, particularly in Thoreau’s work, resembled an ontological claim to a different life, one not completely devoted to modernity and urbanism (Reference McDonaldMcDonald, 2001; Reference NashNash, 1967).

Yellowstone National Park was established in 1872 in the United States, marking a historical moment in the movement for the protection of the wild, although as historians have subsequently pointed out, the protection of this wilderness required the eviction of Indigenous Native Americans (Reference SpenceSpence, 1999). Yet these divisions between man and wilderness continued, eventually culminating in the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964, where wilderness was defined as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammelled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

Yet the establishment of protected areas (PAs) and the concept of wilderness itself have been harshly criticized. Many pointed out that so-called wild areas were in fact recreated and strictly administered and managed (Reference DenevanDenevan, 1992). Furthermore, social justice concerns were raised, pointing at the violent displacement of people and the enclosing of land that followed the establishment of many parks (Reference CrononCronon, 1996). Despite these criticisms, protecting the wild still drives the expansion of PAs and other area-based measures, which remain among the most common practices for conservation governance as fears over land degradation and the extinction crisis have grown (Reference GroveGrove, 1992). Proposals to expand protected areas continue to play a fundamental role in biodiversity governance (Reference Locke, Coates and BilewitchLocke et al., 2013).

Additionally, a strong ecocentric rhetoric has grown in academic and public discourse, underlining the intrinsic value of nature (including humans) and its inherent right to exist, live and flourish despite human pressures. Such powerful discursive material serves as conceptual – if not philosophical – ground for many political and ecological efforts (see, for instance, the recent proposal to protect half of the Earth and how it is backed by ecocentric thinking [Reference KopninaKopnina, 2016]). This is well captured by Reference Wolke, Wuerthner and CristWolke (2014: 204), who states that “wilderness is about setting our egos aside and doing what is best for the land.”

While this definition retains the ontological claim that wilderness is a limit to human expansion – and that indirectly we can learn from it – it shifts the value of wilderness toward intrinsic (moral, spiritual and ecological) value. This should not come as a surprise when we consider the evolution of environmental concern over the last decades and the rise of biodiversity as a concept. Indeed, the concept of biodiversity itself has often been used to reinforce the narrative of wilderness (Reference NashNash, 1967; Reference UgglaUggla, 2010). As such, the expansion of protected areas and other area-based conservation measures is often grounded in an ecocentric rhetoric, which claims these measures to be a vital solution to achieving global biodiversity targets.

Since 1988, there has been a 400 percent increase in the number of PAs and they now cover 15 percent of the Earth’s surface land. Critics point at this data and argue that, despite this surge in protection, biodiversity has neither been conserved nor restored (Reference ButchartButchart, 2010). This remains a point of debate, as others have argued that the achievements of PAs, despite being insufficient, are relatively positive in terms of biodiversity conservation (Butler, 2015 in Reference Wuerthner, Crist and ButlerWuerthner et al., 2015), while the evidence on PAs mitigating human impacts is more mixed. Many nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and some scientists have advocated that current levels of protection are not enough and more is needed, arguing that protection should be expanded to cover half of the Earth (Reference Dinerstein, Olson and JoshiDinerstein et al., 2017; Reference Dinerstein, Vynne and Sala2019; Reference Locke, Wuerthner, Crist and ButlerLocke, 2015; Reference WilsonWilson, 2016), while for others lower percentages could be enough (Reference Visconti, Butchart and BrooksVisconti et al., 2019) (see also Chapters 11 and 12 for different perspectives on this conservation).

2.4 Nature Defined through Cultural and Ecosystem Services Lenses in Landscapes

In the previous section, we saw that nature has been defined as the counterpart of culture: the physical and biological world dominated by “natural” processes, not manufactured or developed by people. This resulted in the creation of wilderness and to the deployment of PAs. However, some claim that most of what we designate as “natural” areas (e.g. what are designated as Natura 2000 habitats in Europe) are in fact historical cultural landscapes with a high biodiversity value (Reference Hermoso, Mora´n-Ordo´n˜ez and BrotonsHermoso et al., 2018; Reference Pechanec, Machar and PohankaPechanec et al., 2018). Following this logic, “natural” ecosystems are the outcome of a coevolutionary process in which they shape, and are shaped by, new forms of social organization, knowledge, technology and value systems (Reference Howarth and NorgaardHowarth and Norgaard, 1992). With this, the conceptualization of nature has shifted for some from wilderness to that of landscape, in 2000 defined by the European Landscape Convention (European Landscape Convention of the Council of Europe) as “an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors.” This definition emphasizes the dialectic and productive relationship between humans and nature and encourages a move beyond dichotomies.

Other value perspectives correspond to a definition of nature that includes culture. In 2012, the publication of what became known as the “New Conservation Manifesto” (Reference Marvier, Kareiva and LalaszMarvier et al., 2012) added a new set of values of nature to the discussion: instrumental value. In their article, Reference Marvier, Kareiva and LalaszMarvier et al. (2012) argue that conservation in the Anthropocene must move past the idea of wilderness because humans and natural systems are profoundly intertwined. Despite the increasing number of PAs, biodiversity is still in decline due to the fact that conservation cannot succeed if it does not address social issues, they claimed, such as poverty and inequality. Thus, conservation (and conservationists) must “embrace human development and the ‘exploitation of nature’ for human uses, like agriculture, even while they seek to ‘protect’ nature inside of parks” (Reference Marvier, Kareiva and LalaszMarvier et al., 2012). From such a perspective, nature is no longer valued (and conserved) for its intrinsic value, but because it provides humans with services and benefits (Reference PearsonPearson, 2016). In this, the ethical horizon of conservation has changed toward ideas of the sustainable use of nature, and in this context, the establishment of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment and the Ecosystem Services (ES) framework are clear milestones.

2.4.1 The Ecosystem Services Lens

One of the core conclusions of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA, 2001–2005) was the fundamental dependence of human wellbeing on ecosystems through a variety of ecosystem services. Ecosystem services have been defined as the “direct or indirect contribution to sustainable human well-being” (Reference Costanza, de Groot and BraatCostanza et al., 2017), highlighting an anthropocentric and instrumental perspective on nature while acknowledging the intrinsic value of species and ecosystems. Outside of the scientific community, ES gained momentum as well, capturing the attention of the general public and private companies, and becoming firmly settled in the international policy arena (Reference Costanza, de Groot and BraatCostanza et al., 2017). The main merit of the ES framework is that it widened the policy discussion to aspects of nature that were traditionally neglected in decision-making (Reference Schröter, van der Zanden and van OudenhovenSchröter et al., 2014). Ecosystem services approaches have successfully shifted conservationist attention to indirect drivers of environmental change, such as socioeconomic dynamics, and attempted to reconcile ecological knowledge with economic thinking. This marked a clear difference from previous conservation efforts grounded in the idea of “conservation against development” (Reference Gómez-Baggethun and Ruiz-PérezGómez-Baggethun and Ruiz-Pérez, 2011). According to critics, this specific economic turn was instrumental in winning the hearts and minds of policymakers and stakeholders (Ring et al., 2010), but it narrowed down ES to a purely economic discourse, paving the way for the commodification of nature (Reference Díaz, Pascual and StensekeDíaz et al., 2018; Reference Gómez-Baggethun and Ruiz-PérezGómez-Baggethun and Ruiz-Pérez, 2011; see also Chapter 6 of this book for a reflection on market-based approaches and their role in transformative biodiversity governance).

This shift is captured by the creation of “The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity” (TEEB, 2007–2011) research program. Another example of the domination of economic approaches to ES is the increasing attention devoted to terms such as “natural capital,” which aims to embed ecosystem services within the human economy in the form of stocks and assets to be accounted for (Reference CostanzaCostanza, 1991; Reference Costanza, de Groot and BraatCostanza et al., 2017). While the MA and TEEB did not introduce new definitions of nature or biodiversity, their framing and discourse have had an influence on which components of biodiversity were selected as being more or less relevant and fit for analysis (e.g. Reference NorgaardNorgaard, 2010; see also Chapter 5). Responding to these criticisms, some argued that acknowledging ES can be the basis of different types of assessment and need not lead to commodification. While monetary valuations are common, the ES framework still directs attention to the multiple benefits of nature that would otherwise be marginalized in decision-making, including ethical and sociocultural valuations, and ES can be used for nonmonetary assessment of human wellbeing (Reference Costanza, Hart, Posner and TalberthCostanza et al., 2009, Reference Costanza, de Groot and Braat2017; Reference de Groot, Brander and van der PloegDe Groot et al., 2012; Reference Schröter, van der Zanden and van OudenhovenSchröter et al., 2014).

The ES framework, however, is changing. Partly out of concern for a narrow economic framing of the concept, and critiques of the domination of a Western world view embodied in ES, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) has developed a more holistic perspective, known as Nature’s Contributions to People (NCP), in which noneconomic values and non-Western worldviews receive more attention. This is an evolution of the ES concept as it considers different types of contributions, from material to nonmaterial, as a spectrum indicating the nonmutually exclusive nature of different contributions. Thus, for instance, food can be seen as not just material (provisioning), but also linked to nonmaterial values (culture and identity), in addition to other values such as options for the future (e.g. to facilitate climate adaptation). Thus, NCP concepts purport to bring in more real-life nuances to the values held by different peoples to nature (Reference Díaz, Pascual and StensekeDíaz et al., 2018), as all of these values coexist, and are not equally prioritized, which could result in potential conflicts between different stakeholders (IPBES, 2017; Reference Pascual, Balvanera and DíazPascual, 2017).

2.4.2 Biocultural Diversity Lens

One reason for the development of the NCP concept was the lack of attention to nonmaterial aspects of nature. Despite the inclusion of “cultural ecosystem services” in the original ES framework, cultural services were underrepresented, lacked suitable indicators, and encountered difficulty (and reluctance) to quantify them (Reference Satz, Gould and ChanSatz et al., 2013). Notwithstanding these problems, studies on nature–culture relations evolved in parallel to the ES framework and gained prominence on the international agendas of organizations like the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (Reference Bridgewater and RotherhamBridgewater and Rotherham, 2019), culminating in the 1988 Declaration of Belém, which found “an inextricable link between cultural and biological diversity” (Reference Schlebusch, Malmström and GüntherSchlebusch et al., 2017: 652).

From this, the concept of biocultural diversity was coined. Reference Agnoletti and EmanueliAgnoletti and Emanueli (2016) consider the concept of biocultural diversity to be a useful term to represent the dialectic relation between the biological and cultural diversity of a (cultural) landscape. As such, two complementary and reciprocally dependent dimensions exist within biocultural diversity: the human shaping of biodiversity and the evolution of cultural practices related to biodiversity.

Modern humans (Homo sapiens) developed in southern Africa some 260,000 to 350,000 years ago (Reference Schlebusch, Malmström and GüntherSchlebusch et al., 2017), emerging from local dryland ecosystems and later found, through dispersal over the globe, in a multitude of different ecosystems. Through foraging, ancient humans shaped and impacted local ecosystems in a similar way to other animal species. Along with the development of human culture, the use of tools and implements for hunting, and later crop cultivation and the raising and maintaining of domesticated livestock, shaped distinct ecosystem patterns (Reference KüsterKüster, 2003). The continuous harvesting of food, the hunting of animals, and the collection of medicinal and other plants influenced the composition of biological communities over time, making it impossible to distinguish “untouched” nature from human-altered ecosystems. According to Reference MoranMoran (2006), hardly any ecosystem on Earth has not been shaped by human action. Long before the Neolithic, our ancestors modified their environment to facilitate their quest for food. Reference Olsson, Zeunert and WatermanOlsson (2018) shows how the myth of untouched wilderness as a treasure for biodiversity was contested. Joint work by ecologists and anthropologists showed – through observations of tropical forests presumably untouched by humans, like large parts of the Amazon – that the habitat had in fact been used through different forms of shifting cultivation for long periods of time, thereby influencing biological diversity. This should therefore more accurately be called biocultural diversity (Reference Gómez-Pompa and KausGómez-Pompa and Kaus, 1992). Similar results and interpretations have been confirmed by other researchers (Reference Padoch and Pinedo-VasquezPadoch and Pinedo-Vasquez, 2010), such as the use of fires for hunting in shaping biodiversity (Reference Sevink, van Geel, Jansen and WallingaSevink et al., 2018).

Cultural practices can also view biodiversity as a resource (Reference Bridgewater and RotherhamBridgewater and Rotherham, 2019). An important aspect to highlight here concerns the meaning of culture, for which Reference CocksCocks’ (2006) work is central in arguing that biocultural diversity has so far been linked to the cultural activities of local and Indigenous groups. In his view, this is too limited and should be extended to include non-Indigenous groups, based on observations of the variety of cultural practices regarding the use of wild plants by non-Indigenous peoples (Reference CocksCocks, 2006).

This dialectic relation between nature and culture remains at the core of biocultural diversity and characterizes both rural and urban landscapes (Reference Elands, Vierikko and AnderssonElands et al., 2019). Examples include seminatural vegetation, like grasslands and West-European heathlands. In seminatural grasslands in Europe, biological communities (plant species and their associated insects and other organisms) depend on continuous interference by humans, such as through fire, mowing or grazing by large herbivores like domesticated livestock. Without such activities, the seminatural grassland will return to forest and lose species richness (Reference Babai and MolnárBabai and Molnár, 2014). Some of these grasslands existed in prehuman times and were shaped and maintained by wildfires and large wild herbivores, but the extent of seminatural vegetation from the Neolithic onward is due mainly to human interference (Reference Olsson, Zeunert and WatermanOlsson, 2018; Reference Oteros-Rozas, Ontillera-Sánchez and SanosaOteros-Rozas et al., 2013). Another example relevant for agricultural systems is that of biocultural refugia (Reference Barthel, Crumbley and SvedinBarthel et al., 2013). This concept directly relates to human food provisioning, as embracing (biocultural) diversity can be seen as an agricultural strategy, and involves ensuring crop and habitat diversity as important tools for resilience in facing different disturbances and uncertainties, as well as the effects of climate change.

In Europe, traditional agricultural landscapes are often abandoned or transformed into urban or more intensively managed agricultural areas (Reference AgnolettiAgnoletti, 2014; EEA, 2010; 2015; 2020). When abandoned, native shrubs, trees and invasive alien species may spread. Local farmers often perceive these changes negatively: from a landscape-in-order where “each corner had a role,” reverting into a landscape-in-disorder that is “getting wild” (Reference Babai and MolnárBabai and Molnár, 2014; Reference Ujházy, Molnár, Bede-Fazekas, Szabó and BiróUjházy et al., 2020). This “getting wild” causes loss of cultural practices and associated biocultural diversity (Reference Agnoletti and RotherhamAgnoletti and Rotherham, 2015), offering an interesting comparison with the interpretation of wilderness in the context of PAs given earlier. What is seen as the loss of biocultural diversity from the perspective of cultural landscapes from a traditional ecological point of view is often framed as a positive gain for biodiversity because land abandonment offers possibilities for “rewilding” (Reference Agnoletti and RotherhamAgnoletti and Rotherham, 2015). Reference AgnolettiAgnoletti (2014) acknowledges this tension and complains that many conservation approaches are too guided by the concept of wilderness when dealing with cultural landscapes, thereby neglecting biocultural diversity.

Frameworks are emerging for the conservation of landscapes that are coproduced by humans and nature, such as in the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Category V (Protected Landscapes/Seascapes) (Reference Schneiders and MüllerSchneiders and Müller, 2017; IUCN, n.d.). Furthermore, cultural aspects are included in discussions of the CBD regarding the establishment of “sustainable use” as one of the three main goals of the convention, which hints in the direction of valuing cultural landscapes (Reference Bridgewater and RotherhamBridgewater and Rotherham, 2019). Another noteworthy development is that of the “Other effective area-based conservation measures” (OECMs) introduced by Aichi Target 11, which allow other sustainability-related goals along with conservation objectives in management and governance (Reference Laffoley, Dudley and JonasLaffoley et al., 2017).

An important step toward the protection of cultural landscapes and biocultural diversity is the increasing attention in the conservation debate to so-called relational values. Reference Chan, Balvanera and BenessaiahChan et al. (2016: 1462) argue that “[f]ew people make personal choices based only on how things possess inherent worth or satisfy their preferences (intrinsic and instrumental values, respectively). People also consider the appropriateness of how they relate with nature and with others, including the actions and habits conducive to a good life, both meaningful and satisfying. In philosophical terms, these are relational values.” The introduction of relational values aims to capture another dimension that can support the concept of biocultural diversity by enriching understandings of human–nature interactions within the landscape.

In conclusion, the introduction of concepts like ecosystem services and biocultural diversity have broadened the horizons of biodiversity conservation in the past decades, shifting the attention from wilderness protection to also include sustainable use and cultural landscapes, from intrinsic values of nature to a plurality of other values, including instrumental and relational. These concepts have been important influences on how biodiversity governance is conceptualized and practiced, as seen in the development of numerous international policy agendas and new forms of protection. The two frameworks discussed in this section emphasize different elements and can complement each other (Reference Bridgewater and RotherhamBridgewater and Rotherham, 2019; Reference Buizer, Elands and VierikkoBuizer et al., 2016). However, tensions exist, particularly on issues of quantification and monetization at the center of discussion within the ES framework that run the risk of objectifying and separating nature from humans.

2.5 Nature Defined as Rights of Nature

In the previous sections, we described the processes that led to the inclusion and engagement with a plurality of values and knowledge systems within mainstream conservation. This is all the more needed when one considers the importance of Indigenous Peoples and local communities (IPLC) in managing and meeting global biodiversity targets. These groups use, manage, own or occupy a quarter of the globe, including 35 percent of the formally protected land area (Reference Garnett, Burgess and FaGarnett et al., 2018, Reference Díaz, Settele and BrondízioIPBES, 2019). Despite globally-declining biodiversity trends, nature is declining less rapidly in these IPLC-managed lands (Reference Garnett, Burgess and FaGarnett et al. 2018, Reference Díaz, Settele and BrondízioIPBES, 2019).

Indigenous and local knowledge systems are mobilized by IPLC, who live within natural and rural settings and make a living through an intimate relationship with nature (UNESCO, n.d.). Examples of different conceptualizations of nature from Indigenous communities include Pachamama (Mother Earth) or Country (Australia) (Reference McElwee, Fernández‐Llamazares and Aumeeruddy‐ThomasMcElwee et al., 2020). Across many communities, nature is considered to be reciprocal kin, such as a mother or a deity, signifying a harmonious relationship between nature and humans (Reference Cano PecharromanCano Pecharroman, 2018). For instance, the concept of Pachamama, despite differences across populations using the term, translates into an actual philosophy of life (“buen vivir” in Spanish) that permeates the daily life and practices of these communities. The formulation of buen vivir as an alternative to modern Western ideas of development has been embraced by numerous social mobilizations (Reference GudynasGudynas, 2011; Reference Kothari, Demaria and AcostaKothari, Demaria and Acosta, 2014). Once again, multiple definitions of nature and the worldviews articulated around it play a role in shaping proposals for conservation governance and, more broadly, sustainability.

Rights of Nature (RoN) is an emerging legal framework that aims at integrating IPLC knowledge with Western legal systems (also see Chapter 9). It has gained vast momentum over the last decade and confers legal rights to individual ecosystems (or the whole of nature) that are then represented in court by one or more legal representatives or guardians (Reference Cano PecharromanCano Pecharroman, 2018). These changes in the legal system around nature represent a fracture with previous approaches (Reference Chapron, Epstein and López-BaoChapron et al., 2019), as proponents argue that the mainstream Western legal system is anthropocentric and legalizes environmental exploitation for the fulfillment of human needs (Reference BurdonBurdon, 2011). Nature, in an ecocentric legal system, would thus be recognized a legal entity and be conferred with the status of legal subject (Reference O’Donnell and Talbot-JonesO’Donnell and Talbot-Jones, 2018). Starting from local ordinances in the United States, RoN have been included in the Ecuadorian Constitution in 2008, and in 2011 Bolivia passed its own Law on the Rights of Mother Earth. More recently, in 2016, the Atrato river in Colombia was given legal personhood, quickly followed by the Whanganui river in New Zealand (2017) and the Ganga and Yamuna rivers in India (2017). In 2019, Lake Erie in Ohio, United States, was granted the rights “to exist, flourish and naturally evolve” (Lake Erie Bill of Rights Charter Amendment 2018), and a proposal to confer legal rights to the Dutch Wadden Sea has recently been discussed (Reference Lambooy, van de Venis and StokkermansLambooy et al., 2019).

The RoN framework poses an ontological quandary because it introduces nature as a subject, rather than object, not only in legal but also in moral terms (Reference de Sousa Santosde Sousa Santos, 2015). Yet, as detailed in the previous sections, such a conceptualization of nature may perhaps be less obvious in the context of the traditional Western ontological divide between nature and culture. The challenge lies in the fact that Western national legislations and worldviews, traditionally anthropocentric, are now confronted with IPLC conceptualizations of nature and of life. Rights of Nature thus is more than a mere legal tool, as it can create encounters between different epistemologies and ontologies, as Western concepts such as “rights” and “ecosystem” meet with Indigenous worldviews and concepts such as ”Pachamama” and “buen vivir” in what has been defined an “epistemic pact” (Reference Valladares and BoelensValladares and Boelens, 2017).

The establishment of RoN presents fundamental questions concerning the way we relate to and see nature. From a conservation point of view, the narrative around nature as a subject and nature’s intrinsic rights, as defined within “ecocentrism” (Reference Washington, Taylor, Kopnina, Cryer and PiccoloWashington et al., 2017), has been widely deployed for the conceptual backing of PAs expansion (Reference KopninaKopnina, 2016). However, ecocentric approaches are contested by critics for their lack of attention for the human dimension (Reference Büscher, Fletcher and BrockingtonBüscher et al., 2017; see also Chapter 12 on Convivial Conservation). Similarly, RoN is criticized for the risk of pitting humans against nature and neglecting human needs that are embedded in nature (Reference Kothari and BajpaiKothari and Bajpai, 2017). As such, ongoing discussions on who will represent nature and how legal representatives or guardians will play a role in trying to address these issues might offer useful examples for broader conservation debates on whether and how to integrate ecological and social concerns.

In 2016, the Colombian Constitutional Court recognized the Atrato as subject and assigned “biocultural rights” to recognize the inextricable connection between the river and local practices and culture. These biocultural rights formed a framework wherein conservation objectives relating to the river were reconciled with the sociocultural needs of local communities (Reference Kauffman and MartinKauffman and Martin, 2018; Reference RoncucciRoncucci, 2019). While promising, the Atrato case is relatively recent and more time is needed to draw any conclusion regarding the success (or not) of integrating environmental and sociocultural needs.

Ultimately, the integration of the Rights of Nature with the rights of people is contested, as it brings us back to the nature/culture divide and to the risk of seeing humans (or rather, some humans) as separated from and opposite to nature. Nonetheless, the inclusion of Indigenous knowledges and worldviews as exemplified by RoN frameworks is contributing to transformative biodiversity governance by proposing novel hybrid legal arrangements and by challenging dominant Western ontologies and epistemologies.

2.6 Scenarios of Nature

In this section, we deal with scenarios of nature as a way to develop future pathways that are inclusive of the plurality of definitions and values of nature encountered thus far. Scenarios of nature are qualitative and quantitative descriptions of a desirable nature future and are widely employed in environmental policymaking. Reference Díaz, Pascual and StensekeDíaz et al. (2018) note that most scenarios do not take into account the complexity of human–nature relations, but in fact only consider human impacts on nature, neglecting the importance of nature in supporting human wellbeing. To remedy this and to include a plurality of values of nature into scenario exercises, a new framework is being developed by IPBES, known as the Nature Futures Framework (Reference Pereira, Davies and den BelderPereira et al., 2020), where the three value perspectives discussed in this chapter (intrinsic, instrumental and relational) would be used to develop future visions for society and nature.

Similarly, the Nature Outlook study by PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency elaborated four perspectives based on different values of nature and explored alternative futures at the EU level (Reference Van, Prins, Dammers and VonketVan Zeijst et al., 2017). The result was the development of four perspectives underpinned by different value assumptions: strengthening cultural identity, allowing nature to find its way, going with the economic flow and working with nature. This exercise did not aim to identify one optimal way forward but rather to facilitate imagining alternative futures. These types of exercises are fundamental for thinking about transformative change because they allow scope for alternatives and create space for confrontation and decision-making with transparent values and inclusive practices.

A key element that is relevant for transformative biodiversity governance is that every perspective of nature comes with different sociocultural, political and economic implications for the future. At a policy level, prioritizing the intrinsic value of nature will result in adopting conservation strategies, envisioning human–nature relations or recalibrating the economic system in a very different way than if relational or instrumental values were prioritized. Moving across perspectives of nature, prioritizing one over another and referring to biodiversity instead of Mother Nature (or vice versa) imply different future worlds. This makes biodiversity governance a contested field, characterized by continual negotiation between different ontologies and epistemologies. The key to transformative biodiversity governance lies in the capacity to embrace and handle this contestation and negotiation without denying the radical value-based differences between perspectives but rather finding ways for them to coexist.

2.7 Discussion and Conclusion

This chapter introduced how different conceptions of nature have developed over time and in different geographies, as well as how different normative value perspectives shape and are reproduced by these definitions of nature. Ultimately, these conceptions and values influence strategies and targets for conserving and using nature. At the core, the nature/culture divide has been a foundational dichotomy in the way nature comes to be defined. While this divide has been criticized both within and outside the Western context in which it was created, nonetheless, it remains essential to much of the debate around conservation.

We argue that defining nature is far from an objective and conflict-free exercise. On the contrary, defining nature is a value-laden task with theoretical and material repercussions. Choosing one definition and value of nature over another implies imagining and advocating for different worlds and nature futures. It means legitimizing one worldview over another. While this is inevitable, we must be aware of the implications for transformative biodiversity governance. Defining nature as wilderness generates conservation strategies that are not only different but possibly at odds with conservation strategies deriving from other conceptualizations of nature.

In this regard landscapes, ecosystem services and biocultural diversity are concepts that, despite differences, aim at integrating human and natural systems. Conservation strategies stemming from these concepts require a different approach to that of traditional protected areas, and much work remains to be done to understand how to integrate different strategies. It is important for transformative biodiversity governance to avoid reductionist approaches that smooth over important ontological or epistemological differences and to embrace pluralistic approaches, as well as to envision governance tools and mechanisms to navigate the political space offered by these multiple perspectives, such as legal Rights of Nature. Additionally, it will also be important to understand what pluralism materially means in terms of biodiversity governance. Does pluralism mean developing hybrid conservation strategies and targets that include multiple perspectives of nature? If so, it would be necessary to first reflect on the extent to which current strategies and targets (at both local and international levels) are receptive of this or, if not, how they favor – more or less implicitly – some perspectives over others.

Another crucial point for transformative biodiversity governance is that of transparency and clarification of choices. Many concepts and approaches are presented as “black boxes,” without a clear view of the premises, rationales, norms and values included. This treats concepts and governance approaches as “truths,” which is problematic for multiple reasons. Firstly, it hides (or at best marginalizes) any uncertainties, unknowns, discordant voices and ambiguity that may exist behind a concept. For example, in our discussion of the concept of “biodiversity,” we noted that it did not emerge from a general consensus within the scientific community, and from the outset its usefulness was criticized.

The second problem that stems from treating concepts and approaches as truth-claims is that it makes them less open to influence by other perspectives. This is at odds with the new attention to inclusivity, plurality and justice that is emerging in biodiversity governance, and that is seen in recent multiperspective scenario exercises. In these, the objective was not to identify one single optimal vision for the future but, on the contrary, to create a space where multiple visions could come together and be realized. Truth-claims that do not acknowledge disagreement and diversity become markedly less tenable given calls for inclusivity and plurality. This requires a serious rethinking of the concepts and the practices that are employed in the name of biodiversity conservation, in order for those who deploy these concepts to become more self-reflective and aware of their own limits and of the values they hold.

3.1 Introduction

The Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (the Post-2020 Framework) is expected to embody transformative change through the adoption of the framework’s “Theory of Change” (CBD, 2020). Its implementation must recognize that the global biodiversity governance architecture needs to transform to lead the required personal and social transformations, including shifts in values, beliefs and patterns of social behaviors (Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016), necessary to successfully tackle biodiversity loss. Against this backdrop, the overarching goal of this chapter is to analyze what needs to be transformed in global biodiversity governance, including institutional structures that shape values, beliefs and behavioral change. The chapter examines obstacles and opportunities for transformation, with the indirect objective of informing implementation of the Post-2020 Framework; at the time of writing, the CBD is expected to adopt the Post-2020 GBF in 2022.

The chapter firstly introduces the key global biodiversity treaty, the 1992 UN Convention on Biological Diversity, and its principal institutional body, the Conference of the Parties (COP) (Section 3.2). The evolution of the CBD is analyzed along with its procedural mechanisms, including its decision-making and review mechanisms. Secondly, the chapter presents the other relevant international institutions in what constitutes the “regime complex” for global biodiversity governance (Section 3.3). Within this complex, biodiversity governance takes place at multiple levels, from global to local, and in different sectors, including some of those most responsible for biodiversity loss such as agriculture, trade and development. The evolution of biodiversity governance beyond the CBD is also explored by analyzing the role of private actors, including business and civil society, in global biodiversity governance. Thirdly, the implementation of global biodiversity laws and policies is examined through global and national governance processes (Section 3.4). The final section draws upon the analyses to propose ways to transform and strengthen global biodiversity governance (Section 3.5), before concluding. The chapter is mainly based on legal analyses, while also drawing on more generic biodiversity governance literature.

3.2 The Convention on Biological Diversity

3.2.1 The CBD, from Seed to Sapling

The CBD opened for signatures at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, known as the Earth Summit, in Rio in 1992, marking the start of the “postmodern era” of environmental regulation (Reference Sands, Bodansky, Brunnée and HeySands, 2007). The Convention, having now near universal ratification (with the major exception of the United States), marked a paradigm shift, from earlier species-specific and ecosystem-based nature conservation conventions to a holistic and development-oriented approach to biodiversity. The CBD is a framework convention that sets out basic principles, general objectives, and rather broad and qualified provisions. The three objectives are biodiversity conservation, sustainable use, and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits. Legal polycentricity, intergenerational responsibilities, and the need for inclusive and participatory processes were new concepts recognized by the treaty (Reference Sands, Bodansky, Brunnée and HeySands, 2007).

In addition, three legally binding protocols have been agreed to date under the CBD Art 28 mechanism: the 2000 Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, the 2010 Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the 2010 Kuala Lumpur Supplementary Protocol on Liability and Redress (Supplementary to the Cartagena Protocol). While these protocols cover the second and third objective of the CBD respectively, it is remarkable that no protocol has been agreed relating to the first objective of the CBD, biodiversity conservation. Thus, the first objective has been addressed by the COP only through its non-legally binding instruments like strategic plans, visions, goals and targets, decisions, guidelines and recommendations.

The design of CBD targets has improved since the first broad “2010” biodiversity target, which called state parties “to achieve a significant reduction of the current rate of biodiversity loss at the global, regional and national level by 2010 as a contribution to poverty alleviation and to the benefit of all life on earth” (CBD COP6, 2002). This target was unmet and superseded by the 2020 strategic plan and the twenty Aichi Targets (ATs), agreed at CBD COP10 in 2010 (see Chapter 1). The ATs were designed to be SMART (specific, measurable, ambitious, realistic and time-bound) and to improve the initial 2010 target (Reference Harrop and PritchardHarrop and Pritchard, 2011). However, well before the 2020 deadline it was clear that most of the ATs would not be achieved (IPBES, 2019; SCBD, 2020).

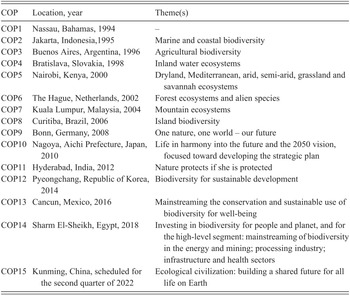

3.2.2 An Active Body: The CBD COP

The CBD COP is the governing body of the CBD, where state parties make decisions by consensus to advance implementation of the Convention. It is in a unique position to strengthen global biodiversity governance to steer change. The COP can advance the evolution and implementation of the CBD by (i) agreeing and furthering ambitions through decisions that are soft law but guide parties, and (ii) creating a space to positively encourage and promote implementation of obligations. It creates a space for the development of shared understandings of the legal regulation of biodiversity, and norms through the elaboration of guidelines on various topics. The thematic priorities of COPs (see Table 3.1) have changed from predominantly ecosystem-based themes (COP1–COP9) to addressing the main drivers of biodiversity loss (COP10–COP14). Themes of earlier COPs do not necessarily tally with their focus or substantial outcomes. For example, COP7’s theme was “Mountain Ecosystems” and, while a work program on this theme was adopted, more notably a work program on protected areas and the Addis Ababa principles on sustainable use were also adopted, which received more attention and subsequently are seen as more important. Changing narratives indicate the broadening of agendas of the CBD and the themes of more recent COPs better match their outcomes.Footnote 1 COP15 follows this trend and hooks onto an important concept: “Ecological Civilization: Building a Shared Future for All Life on Earth.”

Table 3.1 CBD COP themes

Due to the broad scope and comprehensive character of the CBD COP, it is essential that there is buy-in from a very wide range of actors. The Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) responsible for developing the Post-2020 Framework utilizes a theory of change approach to guide the development of a nature framework for all, not just for signatories from the Ministry of Environment, but for the whole of government, multilateral institutions, Indigenous People and local communities (IPLC), nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and business. This could be challenging. A study of the 2016 CBD COP13 in Cancun, Mexico, found a poor representation of government ministers from the economic sectors from both the global north and south, indicating the limited buy-in of biodiversity negotiations nationally, and that disadvantaged actors from the global south were unable to participate as effectively in negotiations due to the limited size of their delegations and lack of expertise to cover all agenda items (Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019). This unbalanced dimension creates power dynamics that are problematic in consensus decision-making and in creating obligations that rest on genuine shared understandings: not all relevant actors are present and exposed to the processes of influence and persuasion at COP meetings (Reference BrunnéeBrunnée, 2002; Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019).

The CBD COP has a long history of engagement with stakeholders such as women, children and youth, NGOs, local authorities, trade unions, business and industry, science and technology, and farmers as observers to its meetings. IPLC have a well-established engagement and influence that is unique for the CBD compared to other intergovernmental processes (Reference ParksParks, 2018). Such nongovernmental actors are central actors in international environmental regimes including the CBD (Reference Spiro, Bodansky, Brunnée and HeySpiro, 2007), exerting influence through: domestic political processes such as rallying voters, lobbying law makers, disseminating information, bringing legal actions and working with media and academia (Reference Chayes and ChayesChayes and Chayes, 1995); advancement of domestic NGO agendas in the international sphere (Reference Spiro, Bodansky, Brunnée and HeySpiro, 2007); and agenda-setting (Reference Arts, Mack and FalknerArts and Mack, 2006). Nongovernmental actors also take on certain key functions within international negotiations, including supplying policy research and development to states (for instance, the 5th Global Biodiversity Outlook is a product of “collected efforts” including individuals from nongovernmental organizations and scientific networks), supplying information on compliance,Footnote 2 facilitating negotiationsFootnote 3 and participating in national delegations (Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019).

A specificity of the CBD COP has also been its ambition to include businesses in its activities. A 2006 COP decision on business participation defines a “business and biodiversity” agenda.Footnote 4 Subsequent COP decisions aim to facilitate private sector engagement and encourage businesses to “adopt practices and strategies that contribute to achieving the goals and objectives of the Convention and the Aichi Targets” (COP12 Decision XII/10). A Global Partnership for Business and Biodiversity and a Business and Biodiversity Forum have been established, and the 2017 Business and Biodiversity Pledge has 141 signatories, including some large corporations such as Monsanto, L’Oréal and DeBeers; however, most relevant multinational corporations to biodiversity loss are not signatories. Despite these decisions and initiatives on business, to date the level of business involvement has been less than aimed for by the CBD COP (Reference van Oorschot, van Tulder and Kokvan Oorschot et al., 2020).

The CBD stresses the importance of “mainstreaming,” that is, the inclusion of biodiversity considerations into nonenvironmental policy areas that impact or rely on biodiversity (Reference YoungYoung, 2011). Art 6(b) of the CBD requires Parties to integrate the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity into sectoral and cross-sectoral activities. Subsequently, means of furthering mainstreaming have been an endeavor of the CBD COP. The first goal of the 2011–2020 CBD strategic plan, agreed at COP10, was to address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss by mainstreaming biodiversity across production sectors and society (GEF, 2016; GEF et al., 2007; SCBD, 2020).Footnote 5 In addition, COP decisions on mainstreaming have been agreed, and mainstreaming was adopted as the key theme at COP13 and COP14. So far, mainstreaming is mostly considered an issue of policy coherence that is yet to be realized at global and national levels, let alone making significant links with communities such as business to realize the whole of society approach advocated by the CBD.

The CBD has two permanent subsidiary bodies: First, Art 25 of the Convention established an open-ended intergovernmental scientific advisory board, the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA). The SBSTTA provides advice and makes recommendations to the COP and has met twenty-four times from 1995 to 2020. Second, COP12 established a Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) in 2014, whose mandate includes strengthening mechanisms to support implementation of the Convention and any strategic plans adopted under it, and identifying and developing recommendations to overcome obstacles encountered. Due to the soft law nature of most CBD decisions, the CBD has adopted a facilitative approach toward implementation by monitoring national implementation through national reporting (Art 26). Besides, a system of voluntary peer review of National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) and their implementation is under development. The methodology was tested in two countries (Ethiopia and India), and later three countries have been reviewed in a pilot phase (Montenegro, Sri Lanka, Uganda) (CBD, 2020).

3.3 The Biodiversity Regime Complex

3.3.1 The Intergovernmental Components of the Regime Complex

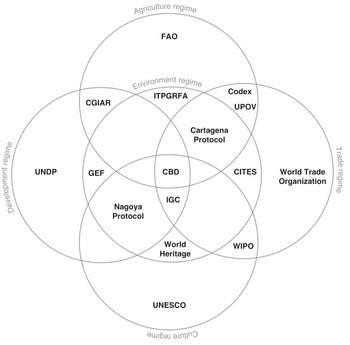

Intergovernmental biodiversity governance has also evolved beyond the CBD. Indeed, due to its comprehensive scope, the CBD has gradually become the central element of a biodiversity regime complex, consisting of five pre-existing international regimes that progressively became regime complexes as well (see Figure 3.1, based on Reference Morin and OrsiniMorin and Orsini, 2014).

Figure 3.1 The regime complex on biodiversity (with a selection of international institutions provided as illustrations of the constituent elements)

CBD: Convention on Biological Diversity

CGIAR: Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research

CITES: Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

FAO: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

GEF: Global Environment Facility

IGC: WIPO Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore

ITPGRFA: International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture

UNDP: United Nations Development Programme

UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UPOV: International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants

WIPO: Word Intellectual Property Organization

The first is the environmental regime. The first objective of the CBD, biodiversity conservation, facilitated interactions between the CBD and a pre-existing cluster of multilateral agreements within the environmental regime. Some of these agreements are biodiversity-related conventions such as the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, the Convention on Migratory species (CMS) and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). In 2007, these conventions started to collaborate in the framework of a broader Liaison Group of the Biodiversity-Related Conventions. The environmental conservation regime also consists of treaties that are not exclusively biodiversity-related, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) (also adopted at the Rio Summit). A Joint Liaison Group of the Rio conventions has been established to enhance coordination and explore options for cooperation and synergistic action.Footnote 6

The second is the agricultural regime. The interactions here are established on a dual basis: agriculture practices are one of the main drivers for biodiversity loss, but agricultural biodiversity is also under threat, and constitutes the basis of food security (IPBES, 2019, see also Chapter 13). How best to manage agricultural biodiversity raises several questions, as agricultural genetic resources are not only important components of biodiversity but also constitute essential food resources (Reference SpannSpann, 2017). In addition, the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the CBD also interacts with the agricultural regime by developing rules concerning the use, especially in agriculture, of genetically modified organisms. The CBD has always considered the agricultural sector to be a priority for mainstreaming.

The third is that of trade. Natural resources, like any other type of good, are traded; and biodiversity is subject to innovation protection, through instruments of intellectual property rights such as patents under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) of the World Trade Organization (Reference Raustiala and VictorRaustiala and Victor, 2004). To counter TRIPS, the CBD stated the principle of state sovereignty over natural resources, which allows states to regulate access to biodiversity within their borders.

The fourth regime is the international development regime. Sustainable development was at the heart of the priorities of the 1992 Rio Summit, which adopted the CBD (Reference Ademola, Casey and BridgewaterAdemola et al., 2015). The development regime includes, among others, financial provisions through, for instance, the Global Environment Facility, to assist developing countries to achieve the objectives of the CBD.

The fifth is that of culture. Originally, the main focus of this regime was on cultural heritage through the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Convention (WHC). The WHC is part of the Liaison Group of the Biodiversity-Related Conventions and is increasingly connected with biocultural diversity, alongside other international policies such as the Nagoya Protocol to the CBD, which recognizes the importance of the traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources (Reference Morgera, Tsioumani and BuckMorgera et al., 2014), and the positive role of IPLC in conservation and the biocultural values that they represent (IPBES, 2019).

The existence of a regime complex is both a strength and a weakness for the CBD (“be at the table or be on the menu”). On the one hand, it ensures biodiversity is “at the table” and the various elements of the regime complex give resonance and amplify the biodiversity issue with its multiple dimensions and values (see Chapter 2). On the other hand, it is a weakness and can be seen to be “on the menu” with more powerful components of the regime deciding the fate of biodiversity. Lack of integrative governance between the different intergovernmental components of the complex, and tensions between biodiversity and the trade, agriculture and development dimensions has led to insufficient attention to biodiversity, as evidenced by poor progress on mainstreaming, and missed biodiversity targets. Policy coherence for biodiversity at the global level is an important precondition for “whole of government” approaches for biodiversity, as is being discussed in the Post-2020 Framework.

3.3.2 Governance beyond the Intergovernmental Realm

Since the 1980s, the institutional landscape of global biodiversity governance has shifted from predominantly public to more private and hybrid (public–private) forms of governance involving private actors (Reference Kok, Widerberg, Negacz, Bliss and PattbergKok et al., 2019; Reference Negacz, Widerberg, Kok and PattbergNegacz et al., 2020). The regime complex has expanded and includes new nonstate dimensions that work across state borders; this is referred to as transnational environmental governance (Reference Bulkeley and JordanBulkeley and Jordan, 2012). Neoliberalism has steered the privatization of state functions and promoted the commodification of biodiversity within global markets, thus shifting power relations (Reference Büscher, Sian, Neves, Igoe and BrockingtonBϋscher et al., 2012). For example, in agricultural commodity chains, public, private and, to a lesser extent, not-for-profit organizations play roles in global environmental governance, extending governance beyond legal and policy regimes.

The broader trend toward increased transnational governance can be seen in biodiversity policy as well as other areas, such as climate change and sustainable development (Reference Bansard, Pattberg and WiderbergBansard et al., 2017; Reference Bulkeley and NewellBulkeley & Newell, 2015; Reference Jordan, Huitema and HildénJordan et al., 2015; Reference PattbergPattberg, 2010; Reference Pattberg, Widerberg and KokPattberg et al., 2019; Reference van Oorschot, van Tulder and Kokvan Oorschot et al., 2020; Reference Visseren‐HamakersVisseren-Hamakers, 2013). An increasing number of nonstate and subnational actors (e.g., cities, regions, business and finance) participate in a plethora of national and international cooperative initiatives with the aim of addressing biodiversity loss (Reference Pattberg, Widerberg and KokPattberg et al., 2019; Reference Visseren‐HamakersVisseren‐Hamakers, 2013).

The increasing importance of nonstate and subnational actors, as well as their formal involvement, poses challenges to a state-based UN process like the CBD and the Post-2020 Framework and its further implementation. Collaboration with transnational actors entered a new stage in 2018 when, at COP14, COP presidencies Egypt and China, with the CBD Secretariat, launched the “Sharm El-Sheikh to Kunming Action Agenda for Nature and People” (Reference Kok, Widerberg, Negacz, Bliss and PattbergKok et al., 2019; Reference Pattberg, Widerberg and KokPattberg et al., 2019). The action agenda’s aim is to raise public awareness about the urgent need to stem biodiversity loss and restore biodiversity for both nature and people; to inspire and implement nature-based solutions to meet key global challenges; and to catalyze nonstate and subnational initiatives in support of global biodiversity goals. The action agenda is hosted on an online platform that has received and showcased commitments and contributions to biodiversity from stakeholders across all sectors in advance of COP15. This platform enables the mapping of global biodiversity efforts and helps to identify key gaps and estimate impact. With such a platform, the CBD follows current governance trends “towards transnational environmental governance and the inclusion of non-state action in multilateral agreements” (Reference Pattberg, Widerberg and KokPattberg et al., 2019: 385). Increasing inclusivity is considered an important element of transformative biodiversity governance (see Chapter 1); this is an important development in contributing to the mainstreaming of biodiversity where it matters as part of integrative governance (Reference Bulkeley, Kok and van DijkBulkeley et al., 2020; Reference Karlsson-Vinkhuyzena, Kok, Visseren-Hamakers and TermeeraKarlsson-Vinkhuyzena et al., 2017), and is being framed as a “whole of society approach” in the Post-2020 Framework.

Within the category of nonstate actors, the important role of subnational actors, cities, regions and local authorities has been recognized in the CBD since 2010. The “Edinburgh process” allows the active participation of subnational actors in consultations, therefore shaping the Post-2020 Framework and targets. With the global growth of urban populations, Reference Puppim de Oliveira, Balaban and DollPuppim de Oliveira et al. (2011) argue that, even though cities are not directly involved in negotiating environmental agreements, they can play a major role in implementation and influence biodiversity conservation (Reference Bulkeley, Andonova and BäckstrandBulkeley et al., 2012). Increasingly, large urban and regional initiatives, such as the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives, or Covenant of Mayors, actively engage in diverse biodiversity activities and policies (see Chapter 14).

The involvement of business and the financial sector in the CBD is more contested. The first COP decision to encourage stronger business involvement was made in 1996 at COP3, but it took until 2010 for a CBD Business and Biodiversity platform to be established. Businesses within primary sectors, which exert direct pressure on biodiversity but also highly depend on it, have started to develop more biodiversity-friendly production methods, see opportunities in developing nature-based solutions and contribute to various sustainability and corporate social responsibility (CSR) goals, although pressure on biodiversity continues to grow (SCBD, 2020). Furthermore, international networks for business and biodiversity are starting to emerge: In 2019, the Business for Nature network was created with the aim of encouraging the adoption of a post-2020 biodiversity transformative agenda.

This diverse and polycentric institutional landscape of global biodiversity governance, described by Reference Pattberg, Kristensen and WiderbergPattberg et al. (2017; Reference Pattberg, Widerberg and Kok2019), is rapidly expanding. Reference Negacz, Widerberg, Kok and PattbergNegacz et al. (2020) and Reference Curet and PuydarrieuxCuret and Puydarrieux (2020) identified 331 international collaborative initiatives forming a crowded and diverse governance landscape, with international collaborative initiatives transitioning from predominantly public to more hybrid forms, including state, market and civil society actors, performing a broad array of governance functions. Most initiatives focus on information sharing and networking, followed by on-the-ground activities, setting standards and certification. Their activities mostly focus on sustainable use and conservation efforts for sectors such as agriculture, forestry and fisheries, rather than solely conservation. The geographical coverage of the initiatives suggests a wide but uneven distribution of activities. The efforts of the initiatives focus on Europe and Africa, leaving areas of high biodiversity in Asia and Latin America with much less attention (Reference Negacz, Widerberg, Kok and PattbergNegacz et al., 2020). Most initiatives monitor their performance, and more than half report their progress annually. Yet, only one-fourth of them has a verification mechanism in place, making review of progress more challenging (Reference Negacz, Widerberg, Kok and PattbergNegacz et al., 2020).

These more inclusive forms of biodiversity governance that commit to action for biodiversity, by a broad coalition of nonstate and subnational actors, could facilitate transformative change for biodiversity by breaking gridlocks in current negotiations through: fostering a nature-inclusive agricultural transition; pushing governments to increase their ambition levels to create a level playing field for front runners; building new multistakeholder coalitions and finding innovative solutions to existing problems (Reference Hale, Held and YoungHale et al., 2013; Reference Pattberg, Widerberg and KokPattberg et al., 2019). Yet, business engagement also raises serious concerns with business taking a powerful role in reshaping the biodiversity regime to its own profit-making agendas (Reference Büscher, Sian, Neves, Igoe and BrockingtonBüscher et al., 2012; Reference Corson and MacDonaldCorson and MacDonald, 2012; Reference MacDonaldMacDonald, 2010; Reference SpannSpann, 2017). Therefore, to avoid greenwashing, it is important to monitor and review progress. However, tracking the impact of international cooperative initiatives on the ground remains a challenge (Reference Arts, Buijs and GeversArts et al., 2017), and the impact, accountability, legitimacy and transparency of transnational biodiversity initiatives require more research (Reference GuptaGupta, 2008; Reference Jones and SolomonJones and Solomon, 2013).

3.4 Implementing Biodiversity Law and Policy

3.4.1 NBSAPs: Strengths and Limitations

National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans provide the foundation for national implementation of the CBD. In fact, their provision in the CBD, Article 6(a), is one of only two provisions that are unqualified and binding on Parties to the CBD whatever the circumstances; the other is Article 26 on national reporting. Its twin provision, Article 6(b), requires state parties to integrate the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity into sectoral and cross-sectoral activities, signaling that such mainstreaming should be a key element of NBSAPs.

An upgrade of the role of NBSAPs was made in 2010 by the inclusion of AT 17, stating that “By 2015, each Party has developed, adopted as a policy instrument, and has commenced implementing, an effective, participatory and updated national biodiversity strategy and action plan.”

In early 2021, 191 out of 196 CBD state parties (97%) have developed at least one NBSAP, among which 169 have been developed after the adoption of the ATs. NBSAP processes have led to a better understanding of biodiversity, its value and what is required to address its threats. However, for many first-generation NBSAPs (developed before the ATs), development processes were more technical than political and did not manage to sufficiently influence policy beyond the remit of the Ministry of Environment (or whichever ministry is directly responsible for biodiversity) (Reference Prip, Gross, Johnston and VierrosPrip et al., 2010).

Second-generation NBSAPs were therefore proposed for the post-2010 period. These include national targets to a larger extent and offer an opportunity for a diversity of actors to engage with biodiversity policies and connect relevant decision-makers within a country (Reference Ademola, Casey and BridgewaterAdemola et al., 2015). However, the potential to “make NBSAPs matter” (Reference Ademola, Casey and BridgewaterAdemola et al, 2015: 105) is challenged using national targets more oriented toward classic nature conservation than systemically oriented to address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss through mainstreaming. Such goals and targets are often expressed in general, aspirational terms, without specifications as to how they could be operationalized. Many countries seem to be at a preliminary stage in terms of mainstreaming because a necessary first step is a basic review of all policies and legislation relevant to biodiversity (Reference Prip and PisupatiPrip and Pisupati, 2018). Moreover, many first-generation NBSAPs have not been endorsed beyond the ministry directly responsible for the CBD, indicating that mainstreaming goals and targets has not always been fully coordinated at the political level. Some NBSAPs specify that this remains to be done (Reference Prip and PisupatiPrip and Pisupati, 2018).

While the post-2010 NBSAPs reveal that biodiversity mainstreaming is gaining recognition, the process is at a very early stage and a considerable amount of political and legal work still needs to be done before tangible results can be achieved on the ground. Considering the missed Aichi Targets, this work needs to be prioritized to address the biodiversity crisis in time.

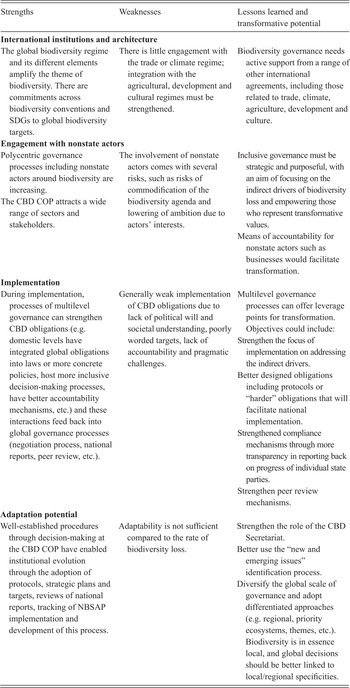

3.4.2 The Implementation Gap