Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Trojan Time Machines

- 1 A Cupboard in Athens: Translating Troy

- 2 A Very Old Book, or How to Predict the Past

- 3 Ladies’ Time

- 4 Queer Time for Heroes

- 5 Hector in the Alabaster Chamber: Ekphrasis and its Discontents

- Conclusion: Trojan Futurities

- Appendix: The Manuscript Tradition of the Roman de Troie

- Bibliography

- Index

- Gallica

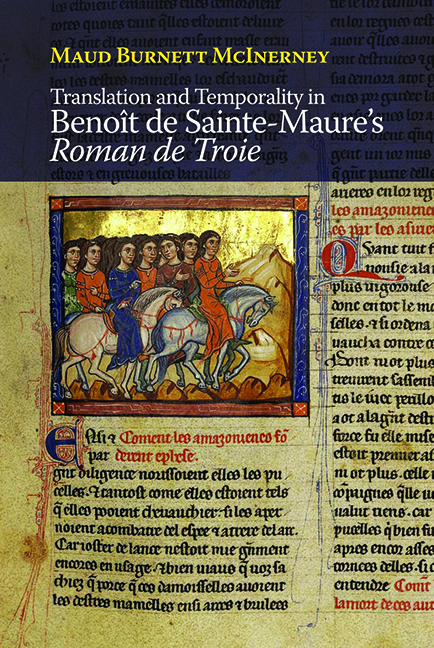

3 - Ladies’ Time

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 October 2022

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Trojan Time Machines

- 1 A Cupboard in Athens: Translating Troy

- 2 A Very Old Book, or How to Predict the Past

- 3 Ladies’ Time

- 4 Queer Time for Heroes

- 5 Hector in the Alabaster Chamber: Ekphrasis and its Discontents

- Conclusion: Trojan Futurities

- Appendix: The Manuscript Tradition of the Roman de Troie

- Bibliography

- Index

- Gallica

Summary

In the generation after Geoffrey of Monmouth, the authors who retold the Troy story and invented the genre of romance took advantage of his central intuition about time: that it was profoundly malleable. In the De Gestis Britonum, as we have seen, time runs in two directions, pressing simultaneously backwards and forwards from the present of the text's composition. The great originality of the next phase of the medieval evolution of the Troy story in the Roman d’Eneas and the Roman de Troie lies in the invention of a new kind of narrative time, a romance time fundamentally at odds both with the baldly teleological historico-fictive time that dominates the narrative of the De Excidio Troiae and with the bi-directional genealogical/prophetic time that shapes the De Gestis. Both of these earlier temporalities are essentially objective, impersonal, and public. As Ricoeur puts it, “in history, death, as the end of every individual life, is only dealt with by allusion to the profit of those entities that outlast the cadavers – a people, nation, state, class, civilization.” The De Gestis is not, except almost coincidentally, the story of any particular individual, even Brutus or Arthur, but of the Kings of Britain as a category (tribal, ethnic, or national); the importance of each king lies only in his relationship, more or less important, to those who come before and after. By contrast, the Roman d’Eneas, the immediate precursor to the Roman de Troie, is not only part of the initiation of a new genre but also helps to invent the temporality that will come to characterize that genre. This temporality, which Bakhtin in “Forms of Time and the Chronotope in the Novel” calls romance time, appears to be subjective, individual, and rooted in a heterosexual erotics that embodies dynastic claims upon the future.3 Romance time, in fact, initially looks like women's time, since it is in the romance that women suddenly come to occupy centre stage. In spite of its association with the feminine, however, romance time in the Eneas will prove uniquely oriented towards the reformation of the male hero and the furtherance of his dynastic interests.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2021