Class- and income-biases in political representation in advanced democratic systems have been documented in many studies. The interests and preferences of citizens in lower income categories or lower social classes are on average less well represented in democratic politics than the interests and preferences of middle- and upper- (income) class citizens. This finding holds both for representation in terms of political attitudes (Bartels, this volume; Giger et al. Reference Giger, Rosset and Bernauer2012; Rosset et al. Reference Rosset, Giger and Bernauer2013; Rosset and Stecker Reference Rosset and Stecker2019), as well as in terms of policy responsiveness, in particular social policies and redistribution (e.g., Elsässer, Hence, and Schäfer 2020; Mathisen et al., this volume; Schakel, Burgoon, and Hakverdian Reference Schakel, Burgoon and Hakverdian2020). In terms of implications and consequences, research on class-biased unequal representation has not only documented representation deficits, but also demonstrated detrimental effects of nonrepresentation, for example, in terms of political participation and alienation (Mathisen and Peters, this volume; Offe Reference Offe, Streeck and Schäfer2009).

Most of these studies assume that voters are aware of “objective” misrepresentation on these issues. However, given data constraints, this is oftentimes hard to study empirically, and we still have rather limited knowledge about the structure and extent of perceived representation. Rennwald and Pontusson (Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021) thus advocate a “subjectivist turn” in the study of unequal representation, in order to better understand the extent, determinants and consequences of grievances caused by misrepresentation. We share their argument that voter perceptions of representation cannot simply be assumed, but rather need to be studied empirically. Moreover, we know little about voters’ perception of representation across different subfields of social and distributive policies. Hence, we need to know both: (a) whether citizens feel badly represented by “politicians” and the political system overall, and (b) whether perceptions of misrepresentation are also manifest when inquiring about specific and tangible welfare policy areas on which parties and elites can intervene. Moreover, placing the focus on how voters perceive representation on specific policy logics and fields sheds light on the complexity of these perceptions. There are reasons to believe that different dimensions of representation (on different principles and areas of social policy) are not identical, and that class differences in perceptions of misrepresentation may vary across them, with potentially relevant implications. If citizens in lower social classes or income groups, for example, perceive a lack of representation when it comes to pensions and unemployment (typical social consumption policies), and citizens of higher social and income classes perceive a lack of representation in the areas of education and childcare infrastructure, both groups of voters may be similarly dissatisfied with representation.

In this paper, we leverage newly collected data from the ERC project “welfarepriorities”Footnote 1 on voters’ social policy priorities, their perception of parties’ social policy priorities, as well as their evaluation of overall social policy representation to study these questions. We focus on social policy as a field that is key to the literature on unequal representation. Indeed, this strand of research has always had a tendency to focus – implicitly or explicitly – on fiscal and social policies when assessing representation and congruence; a focus that is reasonable given that the direct distributive outcomes of these policies could redistribute power relations and reinforce or mitigate patterns of unequal representation.

The chapter is structured as follows: In the next section, we explain why studying perceptions of misrepresentation matters, particularly in what concerns specific welfare policies. We develop hypotheses on the class biases in both party and systemic representation along different social policy dimensions. We also put forward different expectations as to how the presence of strong challenger parties on the radical left and/or the radical right can mitigate some of these perceptions of unequal representation across different systems. The subsequent section presents our data and measures. The analysis section studies class as a determinant of perceived representation by voters’ preferred party and the system overall on different policy dimensions and across different party-political contexts.

Theory

Distributive policies, and social policies in particular, have always occupied a special place in the study of unequal representation. Not only is social policy one of the key areas of state expenditures and material redistribution, it is also an area that affects social stratification and thus very directly links to those material inequalities that structure and exacerbate unequal representation. At the same time, however, social policy and redistribution have always been fields for which representation has been difficult to study because despite extensive divergences in material “objective” class interests in this field, actual attitudinal differences are not very large (Ares Reference Ares2017; Rosset and Stecker Reference Rosset and Stecker2019). Indeed, a wide range of public opinion surveys show that lower-, middle-, and even upper-class citizens on average tend to support expansive, generous social policies (Elsässer Reference Elsässer2018; Garritzmann et al. Reference Garritzmann, Busemeyer and Neimanns2018a; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Enggist and Ares2022), especially when they are asked for their unconstrained preferences. Hence, even though there is evidence of class bias in policy responsiveness, it remains hard to assess unequal representation in this field because of attitudinal convergence on social policy support in mature welfare states.

There is reason to think, however, that this seeming attitudinal convergence masks underlying differences in social policy preferences: a lot of the recent literature has shown that rather than in the level of support, citizens today differ more strongly in the type or field of social policy they prioritize: middle-class support is stronger for policies securing life cycle risks than for policies addressing labor-market risks (Jensen Reference Jensen2012; Rehm Reference Rehm2016); furthermore, while middle-class voters prioritize social investment, such as education and childcare much more strongly than voters in lower occupational and income classes, working-class voters prioritize income protection and social compensation policies, such as pensions or unemployment benefits (Garritzmann et al. Reference Garritzmann, Busemeyer and Neimanns2018; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Enggist and Ares2022). While insiders prioritize employment protection, outsiders prioritize redistribution and employment support (Häusermann, Kurer, and Schwander Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Schwander2014; Rueda Reference Rueda2005). And while working class and national-conservative voters emphasize the protection of national welfare states from open borders, voters in the upper-middle classes and left-libertarian voters prioritize the integration of immigrants and their inclusion in universal social protection schemes (Enggist and Pinggera Reference Enggist and Pinggera2021; Lefkofridi and Michel Reference Lefkofridi and Michel2014). All these conflicts and divergences certainly do occur in a context of overall strong support for welfare states (Pinggera Reference Pinggera2021); however, social policy conflict today revolves as much around prioritizing particular social policy fields than around contesting levels of benefits, redistribution, and taxation in general.

This is why, in this contribution, we focus on (unequal) representation in terms of social policy priorities: do parties (and politicians more generally) attribute similar or different levels of importance to reforms in different social policy fields as their voters? Do parties/elites set other priorities than voters in general and voters from lower social classes in particular? Recent research has emphasized the importance of extending studies of congruence and responsiveness beyond positional measures to also include accounts of the issues and policies that voters prioritize (Giger and Lefkofridi Reference Giger and Lefkofridi2014; Traber et al. Reference Traber, Hänni, Giger and Breunig2022). More importantly, we study these questions through the “subjectivist lens” of voter perceptions. Do voters feel generally unrepresented by “politicians” in terms of social policy? How do voters’ own priorities compare to the priorities they perceive all parties and their preferred party to have?

Answering these questions is relevant to evaluate the extent of the problem of unequal representation, as well as the expected effectiveness of potential remedies to misrepresentation in terms of policies or parties adapting their positions to voters.

Class and Unequal Social Policy Representation

What are our expectations for citizens’ differential subjective perceptions of representation? If subjective perceptions match the abundantly documented patterns of unequal congruence and responsiveness along income (see, among others, Elsässer et al. 2020; Giger et al. Reference Giger, Rosset and Bernauer2012; Lupu and Warner Reference Lupu and Warner2022a; Rosset et al. Reference Rosset, Giger and Bernauer2013), we would expect a class gradient in perceptions of representation: higher social classes should perceive better representation of their policy preferences on the part of political elites, in comparison to citizens in lower social classes. These perceptions could stem both from a class gradient in evaluations of input congruence (how well citizens think their preferences get voted into parliament through elections), as well as of output responsiveness (what decisions elected representatives take on policy). In fact, previous research on class-biased representation (Rennwald and Pontusson Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021) has indicated that middle- and upper-middle class voters feel more congruent with the policy positions of parties and politicians than working-class voters, whenever the preferences of these classes diverge. Rennwald and Pontusson (Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021) identify a clear class hierarchy in voters’ perceptions of being represented by politicians in their countries.

Alternatively, we can also expect that voters could perceive that their voices are equally heard, irrespective of their social class. Since our sample of cases includes many political systems with proportional representation (PR), from a perspective of input representation, these systems typically allow for a wider variety of points of view and preferences to be represented in legislative bodies (Blais 1991). Given the more diversified partisan supply, it should be more likely that individuals of different social classes find a party that represents their interests. Such increased input representation could mitigate perceptions of unequal representation overall.

Finally, a third competing expectation proposes that subjective evaluations of representation are higher among middle-class respondents due to parties’ incentives to mobilize electoral coalitions that include the median voter (Elkjær & Iversen, this volume). Even in PR systems, the process of forming government coalitions can move policy to a moderate compromise that is closer to the demands of the median voter. The centripetal pull during government formation could compensate for centrifugal patterns in electoral competition and bring policy closer in line with the preferences of the middle class (Blais and Bodet Reference Blais and Bodet2006).

Hence, we can formulate three competing scenarios about perceptions of representation: lacking differences in these perceptions by social class, perceptions of comparatively better representation by the middle classes, and perceptions of comparatively better representation by the upper classes. In terms of differences across institutional systems, the first scenario could be more likely to take place in PR systems due to the greater differentiation of the partisan supply and the accompanying input representation. The second scenario should be more likely in majoritarian systems, but could also emerge in PR systems due to the dynamics generated at the government formation and policymaking stages (Blais & Bodet, Reference Blais and Bodet2006).

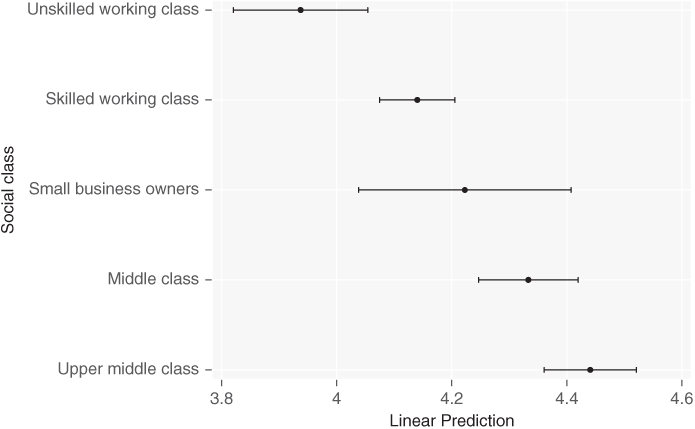

Figure 13.1 indicates that when voters are inquired specifically about social policies – very much in line with previous research on class-biased subjective representation (Rennwald and Pontusson Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021) – we observe a class gradient in perceptions of systemic congruence (i.e., perceived congruence between “citizens” and “politicians” overall), with these perceptions progressively improving as we move up in the social structure, from the unskilled working class, to the upper-middle class.

Figure 13.1 Social classes’ average predicted perceptions of systemic congruence on social policy

Notes: Class as a determinant of perceived systemic congruence. Estimates are based on linear regression models introducing controls for age, sex, trade union membership, and country-FE. The coefficients for all variables are presented in Table 13.A2 in the Appendix.

Figure 13.1 plots social classes’ average evaluation of the extent to which “political decision-makers share your (the respondent’s) views about which reforms in social policy are the most important” (as measured on a 10-point scale). This figure corroborates one of the central tenets of unequal representation studies: the upper classes are indeed more likely to perceive politicians’ (social policy) priorities as congruent with their own. The 0.5-point difference between the upper and unskilled class on this attitude amounts to approximately a fourth of the standard deviation of this variable. This class gradient in perceptions of feeling represented on welfare reform policies is comparable to the findings from Rennwald and Pontusson (Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021).

This initial evidence of unequal systemic congruence substantiates the importance of addressing these perceptions in what concerns social policy. However, this general measure could be masking some substantial heterogeneity in perceptions of unequal welfare policy representation for two reasons. First, while this item captures voters’ perceptions of congruence on social policy generally (without referring to a specific logic or field), it could be conflating perceived policy misrepresentation with some general systemic dissatisfaction (Easton Reference Easton1975), which is usually more widespread among lower class citizens (Oesch Reference Oesch and Rennwald2008; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2007). Second, there are reasons to expect that perceptions of welfare policy congruence are likely to differ across social policy dimensions. In current welfare politics, the literature distinguishes in particular three areas of social policy reform where such class preferences and class perceptions of representation may diverge consistently and substantively: social consumption policies, social investment policies and welfare chauvinism. In these policy fields, voter preferences and party responses may well diverge in different ways.

Social consumption policies refer to those social policies that substitute income in the event of a disruption of employment (e.g., in the case of sickness, accident, unemployment, or old age). They denote the “traditional” passive income transfer policies of the welfare states that were strongly developed in continental Western Europe in the second half of the twentieth century (Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1999). They may be more or less redistributive in their institutional design (depending on the extent to which they are universal, targeted or insurance-based), but they in general tend to equalize income streams between risk groups that relate to social class. For this reason, and because of the immediacy of redistributive effects, social consumption policies are most strongly prioritized and emphasized by working-class voters (as opposed to middle- and upper-class voters) (Garritzmann et al. Reference Garritzmann, Busemeyer and Neimanns2018; Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Enggist and Ares2022). At the same time, the hands of political parties and elites to expand these social consumption policies significantly are rather severely tied by fiscal and political constraints. If anything, elites and governments have generally tried to consolidate (or, in some instances, even retrench) social spending in the main areas of social consumption (e.g., Hemerijck 2012). Hence, we would assume class-specific representation to be particularly biased against working-class interests in the area of social consumption.

By contrast, middle- and upper-class voters tend to attribute a decidedly higher importance to social investment policies than working-class voters (Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Bremer Reference Bremer, Julian, Häusermann and Palier2021). Rather than replacing income, social investment policies invest in human capital formation, mobilization, and preservation (Garritzmann et al. Reference Garritzmann, Häusermann and Palier2022), for example, via education policies, early childhood education and care policies, or labor-market reintegration policies. The stronger emphasis of middle- and upper-class voters – as compared to working-class voters – on social investment has been explained by different mechanisms, in particular the oftentimes regressive distributive effects of these policies (Bonoli and Liechti Reference Bonoli and Liechti2018; Pavolini and van Lancker Reference Pavolini and Van Lancker2018), differences in institutional trust (Jacobs and Matthews Reference Jacobs and Scott Matthews2017; Garritzmann et al. Reference Garritzmann, Busemeyer and Neimanns2018b), and higher levels of universalistic values among the middle class (Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015). However, the efforts of parties and governments to actually expand social investment policies across Western Europe have remained rather limited (Garritzmann et al. Reference Garritzmann, Häusermann and Palier2022) because of institutional legacies, fiscal and political constraints. Hence, when it comes to social investment, one might expect class-specific perceived representation to be less biased overall, or even biased more strongly against the preferences of middle- and upper-middle class voters.

Finally, middle- and working-class voters clearly differ in the extent to which they emphasize the importance of excluding migrants from welfare benefits and prioritizing the needs of natives. Policies that either lower benefit levels for migrants, or which extend existing benefits only for natives generally enjoy stronger support among the lower classes across all countries of Western Europe (Degen et al. Reference Degen, Kuhn and van der Waal2018). The mechanism driving this class divergence is supposed to be either economic (welfare competition, e.g., Manow Reference Manow2018) or value-based (communitarian as opposed to universalistic values, e.g., Enggist Reference Enggist2019). Given the saliency, electoral importance, and much lower fiscal significance of social policies addressing the needs of immigrants, we would expect parties and elites to be more responsive to the, on average, more immigration-skeptical preferences of the lower middle and working classes. Indeed, related studies have found the class bias in representation to be much weaker when it comes to immigration policies than when it comes to distributive policies (Elsässer Reference Elsässer2018). Hence, like social investment, one may expect weaker class bias or even reversed class bias in perceived representation of welfare chauvinism preferences.

Overall, we would thus expect the class bias in perceived party representation to be strongest when it comes to social consumption, because this is the area where strongly expansionist demands among citizens clash with an agenda of fiscal consolidation or even retrenchment among elites. By contrast, we would expect this bias to be weaker when it comes to social investment and welfare benefits for immigrants.

Within the paradigms of social consumption and investment, we can further differentiate different policy fields, such as pensions and unemployment benefits within social consumption, as well as (higher) education, active labor-market policies and childcare services when it comes to social investment. Regarding these fields, we would overall expect subjectively perceived representation biases to be strongest in those policies that are most salient and important to voters. Based on both the risk distribution and political importance (e.g., Rehm Reference Rehm2016; Jensen Reference Jensen2012; Enggist Reference Enggist2019), this would suggest that we expect stronger biases in the areas of pensions, education, and immigrants’ benefits than when it comes to unemployment support and childcare services.

Social Policy Congruence by Party Configuration

The observation of unequal, class-biased representation entails the question of context conditions that might mitigate or exacerbate the class bias in perceived (in)congruence. Indeed, a more varied political supply in terms of political parties would seem as one potential factor affecting the extent to which citizens perceive their preferences to be adequately represented or not, particularly at the stage of electoral competition. As previous research has indicated, at the government formation and policymaking stages, centripetal pressure to build majorities via coalitions imply that, even in PR systems, policy could be more responsive to middle-class demands (Blais and Bodet Reference Blais and Bodet2006; Elkjær and Iversen, this volume).

The role of nonmainstream parties in diversifying the political supply in terms of representation seems particularly relevant, not only because these parties tend to mobilize voters explicitly with reference to their opposition to the dominant mainstream or government parties (Mair Reference Mair2013), but also because left and right challenger parties have particular incentives to be responsive to their voters in terms of social policy. In particular, right challenger parties tend to mobilize disproportionally among voters from the working and lower middle classes (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). The electorate of left challenger parties is more heterogeneous in terms of social class, but at the same time, these parties tend to emphasize issues of social justice, egalitarianism, and distribution and should thus be particularly sensitive to representing the specific social policy preferences of their electorate.

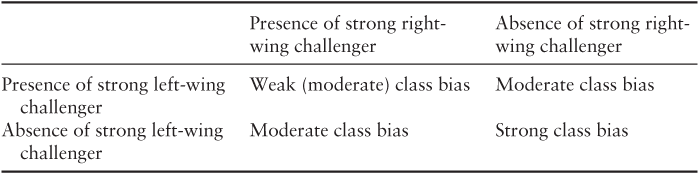

We can thus theorize four context configurations in terms of party supply and derive expectations regarding the class bias in representation (Table 13.1).

Table 13.1 Strength of expected class bias in representation of social policy preferences, depending on challenger parties

| Presence of strong right-wing challenger | Absence of strong right-wing challenger | |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of strong left-wing challenger | Weak (moderate) class bias | Moderate class bias |

| Absence of strong left-wing challenger | Moderate class bias | Strong class bias |

We expect the strongest class bias in perceived representation in systems where challenger parties are weak, such as majoritarian electoral systems that tend to entail obstacles for challenger party mobilization. In these systems, we would expect, in particular, working-class voters to perceive elite congruence among mainstream parties and hence a larger distance between their priorities and the ones of their preferred party or the party system in general. The absence of challenger parties could deteriorate perceptions of unequal priority representation, since these parties tend to improve salience-based congruence (Giger and Lefkofridi Reference Giger and Lefkofridi2014). While we expect challenger parties on the left and right to mitigate some of the class-biased perceptions of representation, this could differ across social policy logics because of the issues these parties emphasize toward voters. Challenger parties on the right mobilize strongly in lower social classes, and they tend to do so, largely, in terms of policies related to immigration and welfare chauvinism (e.g., Hutter and Kriesi Reference Hutter, Grande and Kriesi2016; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Dolezal, Helbling, Höglinger, Hutter and Wüest2012), or of consumptive policies (Enggist and Pinggera Reference Enggist and Pinggera2021). Hence, right-wing challenger parties could particularly mitigate class biases on the logics of social consumption and benefits for migrants. Challenger parties on the left, in contrast, have typically mobilized lower-class electorates on an economic platform, have abstained from anti-immigration stances, and have also attempted to mobilize higher-grade classes on investment-oriented policies. Hence, these parties could mitigate class biases on the social consumption and investment dimensions, but not on welfare chauvinism. We expect class biases in representation to be most strongly mitigated in contexts of diversified supply, with strong challengers on both the left and right.

While these expectations are based on the types of social policy priorities typically taken by different party families (and the social groups they mobilize electorally), deviations from these expectations could arise from how the logic of party competition might affect the salience of these topics. While having a diversified supply can increase the range of policy priorities present in the party system (e.g., with a party explicitly advocating for welfare chauvinism), rising contestation and politicization of issues could also fuel perceptions of lack of representation, if not by voters’ preferred party, then by the system overall. Following the same example, having strong contestation on the issue of welfare chauvinism both from challenger parties on the left and right might bring further attention to welfare chauvinistic voters about the many parties that do not share their position. An expansion in the scope of conflict (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960) can diversify the policy priorities taken by parties, but also highlight the different opinions held by other parties and voters. This is why we also propose that in highly diversified landscape, with challengers on both the left and right, the mitigation of class biases might be lower than initially expected and still be moderate. We purposely leave this expectation rather open and up for empirical investigation.

Data and Operationalization

We use original data from a survey conducted in the context of the ERC project “welfarepriorities.” Data were collected in eight Western European countries with 1,500 respondents each in Denmark, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Spain. The questionnaire and sample design were in our hands, while the actual fieldwork was done in cooperation with a professional survey institute (Bilendi) using their online panels. The target population was a country’s adult population (>18 years). The total sample counts 12,129 completed interviews that were conducted between October 2018 and January 2019. Different measures were taken in order to increase the survey’s representativeness and to ensure high-quality answers. First, we based our sampling strategy on quotas for age, gender, and educational attainment, drawn from national census figures. Age and gender were introduced as crossed quotas, with six age groups (18–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, 56–65, 66 or older) for both female and male respondents. Second, we account for remaining bias from survey response by including poststratification weights adjusting for age, gender, and educational attainment. The full dataset together with some validation tests are presented extensively in a specific working paper (Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Kemmerling and Rueda2020).

Measures of Social Policy Representation

The survey includes a wide range of items capturing social policy positions and priorities, as well as a question on systemic congruence and on the respondents’ evaluation of party priorities.

There are several different items that enable us to measure social policy priorities. For this chapter, we use point distribution questions, in which respondents were asked to allocate 100 points to six policy fields, reflecting the relative importance they attribute to different strategies of welfare state expansion.Footnote 2 The six items were presented in a randomized order, so as not to prime the importance given to them. Through this type of question, we can account for the multidimensionality of welfare preferences, while at the same time we pay respect to the constraint that is inherent in the concept of priorities. At the same time, we do not force respondents to prioritize: the point-distribution question does allow for respondents attributing an equal number of points across all fields or reforms (as opposed to a mere ranking question of the different fields/reforms). Respondents were asked to allocate points to the six following social policy fields, covering social consumption, social investment, and welfare chauvinism: Old age pensions, Childcare, University education, Unemployment benefits, Labor-market reintegration services, and Services for social and labor-market integration of immigrants.

This point distribution question was asked to respondents in the first five minutes of the (roughly) twenty- five-minute survey. Most importantly, in the last third of the survey, the respondents were then again confronted with the same type of point-distribution question. However, the question was then asked with regard to their perception of party priorities. Respondents were asked in which of the above areas they think a particular party would prioritize improvements of social benefits.Footnote 3 Answer fields were identical as above and again randomized. Each respondent had to complete this task twice, once for his/her own preferred party (i.e., the party they indicated they had voted for in the last national election) and once for an additional, randomly chosen party (among the main parties in the country).Footnote 4 Since in this paper, we focus, among other aspects, on “party representation” by the respondents’ preferred party, our sample is restricted to respondents who did indicate they had chosen a party in the last national election.

Overall, and across countries and parties, respondents clearly tended to attribute most importance to the expansion of old age pensions, followed by tertiary education and childcare, followed by unemployment benefits and reintegration measures, and – lastly – integration services for immigrants. However, despite roughly similar patterns across countries, there are significant divergences from the country averages cross-sectionally across party electorates and classes (see Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Enggist and Ares2022).

We present measures of voters’ representation by their preferred party by aggregating the rating of these six specific fields into three different dimensions: social consumption policies (aggregating expansions in the area of pensions and unemployment benefits), social investment policies (childcare, university education, and labor-market reintegration services), and benefits for migrants (services for social and labor-market integration of immigrants). Voters’ priorities on each of these dimensions take the average value of the points attributed across the corresponding fields of welfare expansion. We follow the same aggregation strategy to compute the priorities of the different parties on these three policy logics. Measures of parties’ priorities on each of these logics are based on the average of points allocated to each of these parties by all the available respondents in the sample (i.e., not only their voters). We base these measures on respondents’ average placement of parties and not on the individual placements provided by respondents to avoid risks of endogeneity stemming from voters projecting their own policy stances onto their preferred parties. It is important to notice, however, that parties’ average placement by all respondents or by their voters only is similar. To compute the measure of subjective representation by voters’ preferred party, we simply subtract the party’s placement on each dimension from respondents’ self-placement.

On top of measuring subjective representation by respondents’ preferred party, we also compute a measure of proximity to the party system in general. This measure allows us to add further detail to the question of how distant individuals perceive the party system to be on the three specific welfare policy logics: consumption, investment, and benefits for migrants. This measure captures the average proximity between a voter and all parties in the system and is calculated by first computing the distance between voters’ priorities and those of each party within the system, and second, averaging over these distance measures to arrive to a single measure of subjective system proximity. Both distances (to preferred party and to the party system) are measured on the original 0–100 scale from the point distribution task.

Using such newly developed measures requires evaluations of validity, which we have conducted. First, respondent behavior indicates that they were able and willing to engage with the task at hand: even though they could have eschewed the difficult task of indicating the relative importance for particular policies, fewer than 2 percent of respondents attributed equal point numbers across policy fields. Also, fewer than 6 percent of all respondents attributed 100 points to one field and 0 to all others. We have also conducted extensive analyses to test the internal validity of our items (Ares et al. Reference Ares, Enggist M., Häusermann and Pinggera2019). Regarding the point distribution question, we used data on people’s priorities regarding welfare retrenchment (as opposed to expansion) to test if reported preferences are consistent. Our data show that 85 to 90 percent of respondents gave consistent answers, that is, they did not simultaneously prioritize retrenchment and expansion in the same policy field. Regarding external validity, we find roughly the same “order of priorities” between policy fields as Bremer and Bürgisser (Reference Bremer and Bürgisser2020), who also study the relative importance of social policies.

Determinants of (Non)representation

Our analyses focus on differences in party and system proximity by social class. We implement a market-based definition of social class based on occupational categories. To operationalize class, we rely on a simplified version of Oesch’s (Reference Oesch2006) scheme, commonly used in current analyses of postindustrial class conflict (Ares Reference Ares2020; Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Häusermann, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018). This simplified version of the scheme distinguishes five social classes along Oesch’s vertical dimension, which captures marketable skills – that is, how the labor market stratifies life chances. In descending order, the upper-middle class aggregates professionals (including self-employed professionals) and employers with more than ten employees; the middle class is constituted of associate professionals and technicians; the skilled working class includes generally and vocationally skilled employees; the unskilled working class includes routine low and unskilled workers (in manufacturing, service, or clerical jobs); and a fifth category for small business owners aggregates self-employed individuals without a professional title and employers with fewer than ten employees. All results referring to the priorities and perceptions of small business owners must be considered with certain caution since they constitute a small group in the sample, hence reducing the precision of some estimates. Following many studies of unequal policy responsiveness, we conduct additional analyses that address unequal representation by income groups instead of class by assigning respondents to five income quintiles. While these results also report income biases in social policy representation, they are smaller than inequalities based on social class. This is in line with a growing number of studies repeatedly showing a greater explanatory value of class on redistributive and welfare policies.

The first part of the analyses starts by addressing class differences in party representation on three types of welfare policies (social consumption, social investment, and benefits for migrants) as well as by each of the policies underlying these logics separately. As explained earlier, for each of these logics and policies, proximity is measured with respect to respondents’ preferred party and to the system overall. In these models, the outcome variables are distances in points; hence, the models are estimated as linear regression models including controls for age, sex, trade union membership, and country-fixed effects. These control variables are included consistently across all models (except for the analyses by party system type, which do not include country-fixed effects).

The second part of the analyses addresses how the configuration of the partisan supply could mitigate/accentuate class inequalities in perceived congruence. Since the number of country-level observations is limited to eight, to address this question, we split the sample into four groups depending on whether challenger left- and/or right-wing alternatives had strong electoral support at the last national election. We consider electoral support as strong if either the left- or right-wing challenger block (including one or more parties) receives more than 10 percent of the vote. Following this classification decision, we observe four countries in which the left- and right-wing challenger blocks are strong: Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden. There are two countries in which we do not observe neither a strong left- nor right-wing challenger: Ireland and the United Kingdom. In Spain, there is a strong challenger party on the left only, while in Italy we only find a strong challenger on the right.Footnote 5 Given the reduced number of cases in some of these types of party configuration, we must be cautious in interpreting these results. The figures always indicate the countries on which the models are estimated.

To facilitate the interpretation of the results, they are presented by means of figures displaying average adjusted predictions or average marginal effects. The full models with all control variables are included in Tables 13.A2–13.A5 in the Appendix.

Results

Subjective Social Policy Representation by Preferred Party and Party System

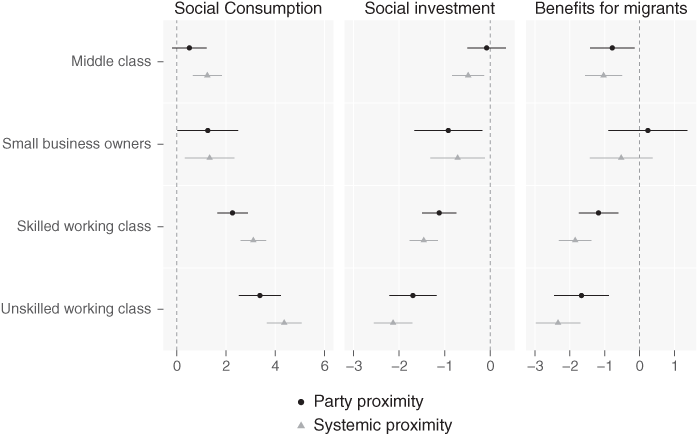

As displayed in Figure 13.1, there are apparent class inequalities in how voters perceive politicians’ social policy priorities in relation to theirs, with working-class voters perceiving politicians as less congruent. This raises the question of whether this perception of unequal representation is also manifest when we focus on more specific welfare policies. To address this knowledge gap, the analyses discussed later model subjective representation by (a) voters’ preferred party and by (b) the party system, on respondents’ social class. Figure 13.2 presents class differences (with respect to the upper-middle class) in how distant voters are from their preferred party and the main parties in the country in terms of their prioritization of different welfare expansion logics: social consumption, social investment, and benefits for the labor-market integration of migrants. Comparing the two different measures – by preferred party and system – allows us to gain some insights about how good/bad representation by voters’ preferred party is, in comparison to the system overall. We could think of a context in which most parties in the system provided poor representation to the demands of the working class, but a specific party mobilized the priorities and electoral support of the lower-grade classes. In such a context, we would observe class gradient in terms of systemic representation, but not on party representation. This is not, however, what Figure 13.2 indicates.

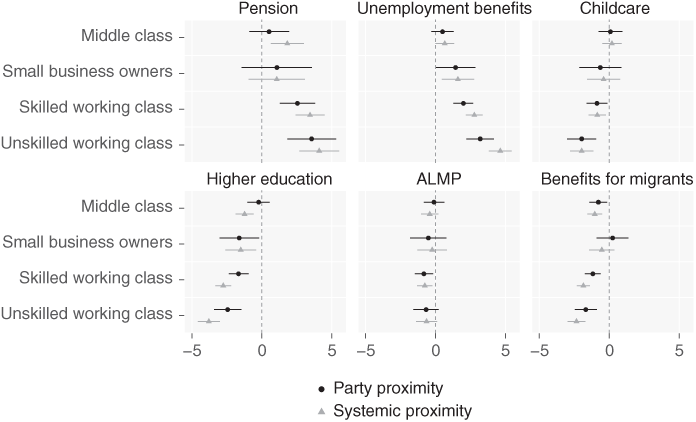

Figure 13.2 Social class differences in proximity to preferred party and party system

Notes: Class as a determinant of proximity across party systems (coefficients indicate differences to the upper-middle class). Estimates are based on linear regression models introducing controls for age, sex, trade union membership, and country-FE. The coefficients for all variables are presented in Table 13.A3 in the Appendix.

Proximity to parties is measured through points distributed to the different areas of benefit expansion, with higher values indicating support for further expansion of benefits in that particular area. Hence, positive party-voter distances indicate that the voter prioritizes expansion to a greater extent than the party (system) does. Correspondingly, negative values indicate that voters prioritize expansion in that area less than parties. In light of the evidence indicating that the working classes tend to prioritize consumption over investment policies, and our expectation that political elites will be more sensitive to investment-oriented expenditure, we should observe a class gradient in subjective proximity to parties. This is, in fact, what Figure 13.2 displays. There are two key findings to take from these analyses. First, social classes differ in how proximate they perceive their preferred party and the party system on the three dimensions of welfare expansion considered. Evaluations of party and systemic representation are better for the upper-middle and middle class than for the working class. On consumption-oriented expansion, the distance to voters’ preferred party is 3.4 points greater for the working class than for the upper-middle class. This difference increases to 4.4 points if we focus on systemic proximity instead. A difference of 3–4 points might seem little, but we should assess it relative to the in-sample range. A four-point difference amounts to about 50 percent of the standard deviation of the consumption proximity measure, this effect is larger than other class differences identified on commonly studied preference variables (like preferences on redistribution, gay rights, or environmental issues) (Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Enggist and Ares2022).Footnote 6

The class gradient is also manifest in party and systemic representation on the expansion of investment and migrant integration but, in this case, with a negative sign. Again, the priorities of the upper-middle classes appear better represented and, in these fields, the lower-grade classes prioritize expansion to a lesser extent than their preferred party (or the party system) – this is reflected in negative measures of proximity. On social investment policies, the distance to their own party is about 1.7 points larger for the unskilled working class than for the upper-middle class. This difference increases to 2.1 when it is measured with respect to the party system. As we expected, unequal representation is larger on the social consumption dimension. The difference between the upper-middle class and the unskilled working class in the proximity to voters’ preferred party is twice as large for social consumption than for investment policies. Hence, it appears that the class bias is lower on the topics of social investment and benefits for migrants, on which the working classes prioritize expansion to a lesser extent than the parties they vote for (and in the system) do.

The second interesting finding stemming from these analyses is that the two measures of class inequalities in subjective representation display a greater similarity than we might have expected. In other words, class differences in perceptions of proximity are similar, whether gauged against respondents’ preferred party or the main parties in the system. While distances to own parties are usually smaller, they still display a class gradient, hence showing that class differences in congruence are manifest even when compared against voters’ preferred party. We take this as a sign indicating that even voters’ preferred party – in a relatively diverse party system, as in most Western European countries – do not eliminate class biases in perceptions of representation. We address to what extent the configuration of the partisan supply can compensate for some of these inequalities in further analyses discussed later.

Additional estimations (included in Table 13.A4 and Figure 13.A1 in the Appendix) address inequalities based on income quintiles instead of social classes. The results portray a similar income gradient in subjective representation. Income differences are smaller than class differences – which is in line with current research highlighting the importance of class for the type of welfare expansion prioritized (Häusermann et al. Reference Häusermann, Pinggera, Enggist and Ares2022). Moreover, there are no income differences in party or systemic representation concerning the expansion of welfare benefits for migrants, which matches the finding that it is not the poorest voters who tend to support more welfare chauvinistic policies (Bornschier and Kriesi Reference Bornschier, Kriesi and Rydgren2013).

Addressing different logics of social policy reform separately returns some interesting divergences. We can disaggregate these analyses further by addressing perceptions of proximity by specific policies. Our initial expectation was that class inequalities should be larger on those policies that are important and salient to a majority of voters – like pensions, education, or immigrants’ benefits. On other policy areas, voters’ attitudes and priorities are less likely to be strong and well defined. Figure 13.3 displays some interesting class differences across policies. The strongest class gradient appears for two social consumption policies that are largely salient across countries and strongly demanded by lower-class voters: pensions and unemployment benefits. As we could derive from the previous figure, class differences are smaller for investment policies, but, moreover, it becomes apparent that unequal distance on this dimension is mostly driven by the prioritization of the expansion of higher education by upper middle-class voters, which is more commonly shared by parties. On childcare and active labor-market policies, we find practically no difference between the distance perceived by upper- or lower-class voters. Hence, across different policies, class differences in perceived party proximity are greater on those policies that are generally more salient to voters.

Figure 13.3 Social class differences in subjective proximity to preferred party and party system, by social policy area

Notes: Class as a determinant of proximity across party systems (coefficients indicate differences to the upper-middle class). Estimates are based on linear regression models introducing controls for age, sex, trade union membership, and country-FE. The coefficients for all variables are presented in Table 13.A5 in the Appendix.

Evaluations of Party Proximity and Systemic Proximity under Different Party System Configurations

The configuration of the partisan supply, particularly the presence (absence) of strong challenger parties on the left and right of the ideological spectrum, could mitigate (strengthen) some of the class inequalities in perceptions of proximity revealed in Figure 13.2. As shown in Table 13.A2 in the Appendix, a more varied party system could improve input representation by providing a wider range of programmatic supply to voters (e.g., radical Right parties explicitly advocating for welfare chauvinistic policies, or radical Left parties promoting consumptive policies) and, moreover, challenger parties have been more successful in mobilizing a working-class support base. This is why we expected class biases in representation to be strongest in systems without strong challenger parties and weakest in systems with left- and right-wing challengers. In systems with strong challenger parties on either the left or right, we expect these class differences to be moderate and to vary depending on the specific social policy logic under consideration.

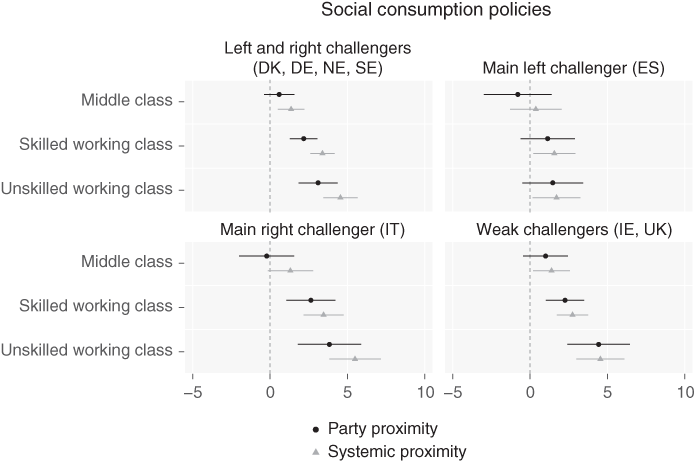

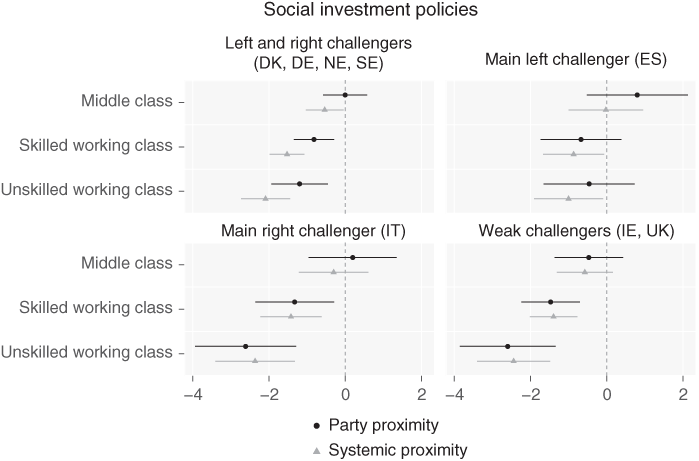

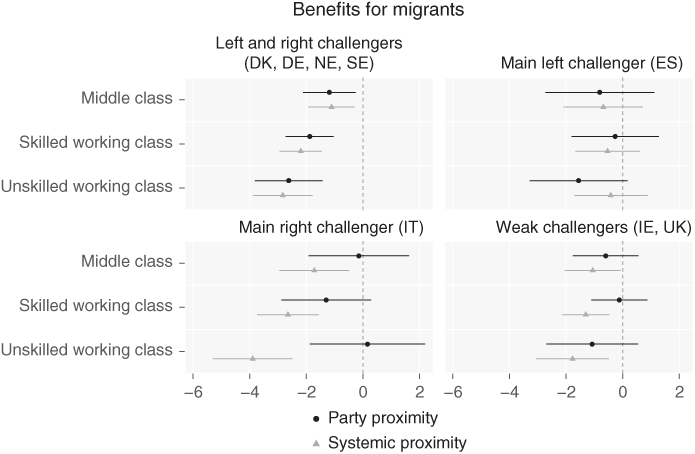

The four panels in Figures 13.4 to 13.6 present average class differences in proximity to the preferred party and to the system by different configurations of the party system. The analyses draw on data from eight different countries, which are not uniformly distributed across the four types of partisan supply. Specifically, only Spain has a party system with a strong challenger on the left exclusively, while Italy represents the only case with a strong challenger only on the right ideological camp.

Figure 13.4 Social class differences in subjective proximity to preferred party and the party system on social consumption across different party system configurations

Notes: Class as a determinant of proximity across party systems (coefficients indicate differences to the upper-middle class). Estimates are based on linear regression models introducing controls for age, sex, and trade union membership. Average differences for small business owners are not presented because they represent a small group in the sample, with a low number of occurrences when the analyses are disaggregated by party system.

Figure 13.5 Social class differences in subjective proximity to preferred party and the party system on social investment across different party system configurations

Notes: Class as a determinant of proximity across party systems (coefficients indicate differences to the upper-middle class). Estimates are based on linear regression models introducing controls for age, sex, and trade union membership. Average differences for small business owners are not presented because they represent a small group in the sample, with a low number of occurrences when the analyses are disaggregated by party system.

Figure 13.6 Social class differences in subjective proximity to preferred party and the party system on benefits for migrants across different party system configurations

Notes: Class as a determinant of proximity across party systems (coefficients indicate differences to the upper-middle class). Estimates are based on linear regression models introducing controls for age, sex, and trade union membership. Average differences for small business owners are not presented because they represent a small group in the sample, with a low number of occurrences when the analyses are disaggregated by party system.

The analyses summarized in Figure 13.4 return two interesting results. First, they indicate that, overall, the trends in unequal congruence identified in Figures 13.2 and 13.3 are persistent across most configurations of the partisan supply. Working-class voters perceive their own party and the system as less congruent with their consumption priorities (in comparison to the upper-middle class) in most of the countries under study. Second, there is one case for which there are no apparent class inequalities in terms of consumption priorities: Spain. In this country, in which the partisan supply is characterized by the presence of a strong left-wing challenger (Podemos), but the absence of one on the right, there are no class differences in perceptions of proximity, either by voters’ preferred party or the system overall. This could indicate that, in a country in which a strong challenger Left party has pursued a clear antiausterity agenda, working-class demands are better represented. However, if class biases were mitigated by the more diversified party supply in general, this absence of a class gradient should also be manifest in those systems in which we observe both a right- and left-wing challenger. This is not what the top left panel in the figure indicates. Moreover, the class inequalities visible under this diversified party supply are not driven by any of the four countries included in this type, but rather consistent across them. Hence, these results do not support our expectation about congruence with the lower-grade classes being improved in contexts of a more diversified partisan supply. Moreover, Figure 13.5 (addressing congruence with social investment priorities) displays a similar pattern. Class differences in perceptions of congruence are rather constant across different party systems with Spain, again, being the exception without a class gradient. Since we only observe one country with a strong challenger exclusively on the left, it is difficult to generalize these results, particularly because Podemos’ agenda strongly emphasized antiausterity economic policies – in response to earlier cutbacks on key welfare policies, including pensions, unemployment benefits, or education.

Finally, Figure 13.6 addresses priorities for the expansion of benefits for migrants. On this dimension, there is some substantive variation in the class differences in congruence manifest across different party systems. In countries with no strong right-wing challenger party (irrespective of whether there is a strong left-wing challenger or not), there are no class differences in perceptions of congruence with voters’ preferred party or with the system overall. In these contexts, parties are equally congruent with all classes. When a right-wing challenger is present in the party system, we do observe a class gradient in perceptions of proximity. Interestingly, in the case of Italy, in which we do not observe a strong contender on the left, the unskilled working class perceives the party system as more distant from their own priorities but not their preferred party. This could indicate that, presumably, radical-right voters perceive their party as congruent with their demands. We have to be cautious, however, in this interpretation, since it is based on a single country observation. In this case, the absence of a class gradient in countries without a right-wing challenger runs against our initial expectation that these parties could channel the welfare chauvinistic demands of the lower classes. However, we can also interpret this absence of class differences along the same interpretation provided for the analyses by policy fields by referring to salience. In countries like Spain, Ireland, and the United Kingdom, immigration has been a less salient topic until more recently. On policies that are less salient to voters (of different class location), it is less surprising to find no class gradient in perceptions of congruence. Overall, the different results do not lend support to the expectation that a diversified partisan supply mitigates class biases in perceived proximity, mostly because we do observe such biases in party systems with challenger parties on both the right and the left. However, the patterns observed for Spain on the logics of consumption and investment, and in Italy on welfare chauvinism seem to indicate that parties could mitigate some of these inequalities.

Conclusion

This chapter set out to address a shortcoming in existing literature which, in spite of profusely documenting the lower policy responsiveness to the interests of lower-income citizens, paid relatively little attention – with some exceptions (e.g., Rennwald and Pontusson Reference Rennwald and Pontusson2021) – to how citizens perceive opinion congruence. We did this by focusing on an area that is particularly relevant to redress material and political inequalities: welfare policy. Leveraging new data on voters’ and parties’ social policy priorities, this chapter has shown that there is a class gradient underlying voters’ perceptions of representation. Lower-grade classes generally report worse perceptions of congruence between politicians’ social policy priorities and their own. Moreover, these class differences are manifest not only when enquiring about social policy in general, but also when voters have to explicitly state parties’ and their own positioning on specific and concrete social policies. The detailed nature of the data allowed us to gauge voters’ assessment of party and systemic representation on three welfare policy logics and six policy fields. Overall, the analyses report a class gradient in the proximity that voters’ report to their own party and to the party system in general. Upper-middle class voters perceive parties’ priorities as closer to their own.

The analyses also revealed some interesting differentiation in the size of class inequalities across welfare policies. Representation (by own party and the system) is more class-biased on those policies that the literature has identified as more salient to voters and to the working class in particular. We find a stronger class gradient in proximity on social consumption policies, in comparison to social investment or welfare chauvinism. Class differences are particularly strong for the expansion of pensions, unemployment benefits, and tertiary education, while they are negligible for childcare and active labor-market policies.

As discussed by Bartels in this volume, by focusing on average differences in the placement of different social classes and political parties on social policy, our analyses do not explore the dispersion of preferences within social classes. In other words, lower average representation of the working classes’ preferences could mask different levels of representation within this class, if variance in preferences among workers is high. In additional analyses (not shown), we study, precisely, the dispersion of social policy preferences by social class. Our results indicate that there are no substantive differences in the variance of these preferences across groups: on consumption, investment, and welfare chauvinistic policies, the difference in variance between the upper and lower class is of 2 points at most.

These results indicate that it might be hard to redress some of these inequalities in congruence. The lower-grade classes prioritize further expansion in those policy areas that represent a bigger portion of social spending (most notably, pensions). It appears very unlikely that parties’ policy platforms will adopt a strongly expansionary pension agenda, moving the system’s position closer to the working class demands. Moreover, voters’ own preferred parties do not seem to fully mitigate perceptions of unequal representation either. Even if distance to preferred party is usually smaller than to the system, it still displays a class gradient. Our expectations about the lower classes possibly being better represented on the issue of investment and, especially, welfare chauvinism are also partly disconfirmed by the analyses. We expected the upper classes to be less well represented on these logics because these groups desire further expansion on investment, which parties could be limited in delivering due to tight budget constraints and because parties might have been more responsive to welfare chauvinistic trends. However, also on these two logics, the higher-grade classes perceive better representation, even if to a lower extent than on the consumption logic. Faced with important demographic and socioeconomic transformations, worse perceptions of congruence might hinder the possibilities for governments to introduce welfare reforms. Responsiveness plays an important role in building a “reservoir of goodwill” on which governments can capitalize to survive difficult periods of more “responsible” but less-responsive decisions (Linde and Peters Reference Linde and Peters2020). The absence of such a reservoir might undermine the capability for parties to make hard choices.

While our analyses allow us to focus, in depth, on a specific and relevant area – social policy – conclusions about the implications of this unequal representation for satisfaction with government and democracy more generally would require a more encompassing focus that also includes other policy areas. Voters could prioritize minimizing distance to parties on other issues not included in our analyses, which would indicate that they perceived these other issues as more salient for the vote choice. In such a case, when voters do not choose the party that is closest to them on the question of welfare reform (or when minimizing this distance is not the only consideration), we might expect class differences in incongruences with one’s preferred party to be less consequential. Additional analyses suggest that voters indeed tend to elect parties that are close to them on social policies, but also that this is not the only consideration, since some of them do vote for parties that are not minimizing distances on this issue. For about 25 percent of respondents, there would indeed be another party (different to the one they voted for) significantly closer to them (10 or more points closer on the 100-point scale). However, there are no apparent class differences in whether voters select the party that is closest to them on social policy.

In a last step of the analyses, we took into consideration whether the configuration of the partisan supply could moderate some of the class inequalities identified in the first step of the analyses. While we expected the class gradient to be mitigated under an expanded political supply with challenger parties on the left and right of the ideological spectrum, this is not what the evidence indicates. In fact, class biases in representation are rather robust across contexts, especially in what concerns consumption and investment policies. The only manifest exception is the Spanish case, for which we do not find class differences in perceived representation. We are, however, cautious to attribute this merely to the presence of a strong radical left challenger because class biases are also apparent in countries in which both left and right challengers exist. Moreover, the Spanish case alone, with a left-wing challenger characterized by emphasizing a strong anti-austerity agenda, may be quite particular. Welfare chauvinism is the only logic for which we observe stronger variation across party configurations. These differences, however, point to issue salience as a potentially conditioning factor. Class biases on welfare chauvinism appear to be smaller in countries in which the salience of the immigration issue is lower. The class gradient is also more moderate on social policies that are typically less salient to the public, like childcare or active labor-market policies. Hence, while strong challenger parties mitigate class biases in some cases (in Spain, or on benefits for migrants in Italy), the relative salience of different issues – affected by an expansion of conflict with the presence of strong challengers on both ends of the ideological spectrum – in turn, rather seems to heighten class biases. Further analyses might attempt to adjudicate between these factors by addressing cases that vary on the two dimensions. Despite the complex context-effects conditioning class biases, however, the main finding of our analysis is the consistent existence of class biases in representation across different areas of the welfare state and social policy.