The seemingly innocuous question “What is wellbeing?” easily leads to passionate debates and much conceptual confusion. This chapter first provides some signposts for a definition of wellbeing. Sound definition of the construct is essential to the measurement of wellbeing and the growth of the science of wellbeing. The emergence of the science of positive psychology and its application through positive psychology interventions (i.e. strategies to increase wellbeing) have created new opportunities to develop wellbeing in individuals, organizations and communities. After positive psychology is defined, key theories of wellbeing and positive psychology are summarized. An overview of key research evidence from positive psychology interventions is then provided. This overview is intended not as an exhaustive review, but rather as a sample to enable readers to explore the fertile interface of the science of wellbeing and positive psychology with the literature and experience of recovery.

What Is Wellbeing?

Responses to the question What is wellbeing? vary greatly depending on whether it is a lay person, health practitioner, person with lived experience of illness, economist, philosopher, psychologist or sociologist answering the question. Lay persons or persons unfamiliar with defining concepts or constructs commonly give examples of situations or experiences that lead to wellbeing, such as having good friends or a good job. A philosophical definition is commonly brief and coherent, but may lack the precision that a scientist is seeking. One philosophical example is the following definition: how well someone’s life is going for them (Crisp, Reference Crisp and Zalta2014).

Philosophers have been arguing over and defining wellbeing for many centuries. Economists have been doing so for over one hundred years. Psychologists and wellbeing scientists are relatively new to this arena. Although recognizing the contributions to this area from philosophers (e.g. the distinction between hedonic and eudaemonic wellbeing) and economists (e.g. the distinction between evaluative and experienced wellbeing), this chapter focuses primarily on empirical attempts to define, measure and increase wellbeing, with particular focus on positive psychology and its related interventions.

In attempting to define wellbeing it is useful to consider several questions from the outset:

1. What is the level of analysis? for example: individual, group, organization, society

2. What domain is being discussed? for example: physical, mental, social

3. Is it to be defined subjectively or objectively?

4. Does it necessarily require the presence of positive attributes? in other words, is it more than the absence of negative attributes such as symptoms of illness?

6. How is it different from health?

Clarity regarding these six questions makes it is easier to locate one’s position within the contested space of wellbeing constructs. Table 2.1 summarizes some key examples of contemporary wellbeing constructs in wellbeing science and positive psychology. Such constructs underpin the emerging health and wellbeing outcome measurement in health and human services. In reading Table 2.1, it is useful to examine the difference between hedonic and eudaemonic assumptions in terms of defining wellbeing. Shorthand definitions often combine these two approaches in phrases such as “feeling good and functioning well” (see Huppert and So, Reference Huppert and So2013).

| Wellbeing construct | Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Hedonic wellbeing | “focuses on happiness and defines well-being in terms of pleasure attainment and pain avoidance” “the predominant view among hedonic psychologists is that well-being consists of subjective happiness and concerns the experience of pleasure versus displeasure broadly construed to include all judgments about the good/bad elements of life. Happiness is thus not reducible to physical hedonism, for it can be derived from attainment of goals or valued outcomes in varied realms” | Ryan and Deci (Reference Ryan and Deci2001b, p. 141) |

| Eudaemonic wellbeing | “The eudaimonic perspective of wellbeing – based on Aristotle’s view that true happiness comes from doing what is worth doing – focuses on meaning and self-realization, and defines wellbeing largely in terms of ways of thought and behavior that provide fulfillment” | Gale et al. (2013, p. 687) |

| Wellbeing | “refers to optimal psychological experience and functioning” “Ryff and Keyes (Reference Ryff and Keyes1995) … spoke of psychological well-being (PWB) as distinct from SWB and presented a multidimensional approach to the measurement of PWB that taps six distinct aspects of human actualization: autonomy, personal growth, self-acceptance, life purpose, mastery, and positive relatedness. These six constructs define PWB both theoretically and operationally and they specify what promotes emotional and physical health” | Deci and Ryan (Reference Deci and Ryan2008, p. 1)Ryan and Deci (Reference Ryan and Deci2001b, p. 146) |

| Psychological wellbeing | “Each dimension of PWB articulates different challenges individuals encounter as they strive to function positively (Ryff, Reference Ryff1989a; Ryff and Keyes, Reference Ryff and Keyes1995). That is, people attempt to feel good about themselves even while aware of their own limitations (self-acceptance). They also seek to develop and maintain warm and trusting interpersonal relationships (positive relations with others) and to shape their environment so as to meet personal needs and desires (environmental mastery). In sustaining individuality within a larger social context, people also seek a sense [of] self-determination and personal authority (autonomy). A vital endeavor is to find meaning in one’s efforts and challenges (purpose in life). Lastly, making the most of one’s talents and capacities (personal growth) is central to PWB.” | Keyes et al. (Reference Keyes, Shmotkin and Ryff2002, p. 1008) |

| Subjective wellbeing | “As an operational definition, SWB is most often interpreted to mean experiencing a high level of positive affect, a low level of negative affect, and a high degree of satisfaction with one’s life …The concept of SWB, assessed in this way, has frequently been used interchangeably with ‘happiness.’ Thus, maximizing one’s well-being has been viewed as maximizing one’s feelings of happiness.” | Deci and Ryan (Reference Deci and Ryan2008, p. 1) |

| Wellbeing | “In 2 large samples, results supported the proposed latent structures of hedonic, eudaimonic and social well-being and indicated that the various components of well-being could be represented most parsimoniously with 3 oblique second-order constructs of hedonic, eudaimonic, and social well-being.” | Gallagher et al. (2009, p. 1025) |

| Social wellbeing | “Keyes (1998) conceived of a five-component model of social well-being: social integration, social contribution, social coherence, social actualization, and social acceptance. These five elements, taken together, indicate whether and to what degree individuals are overcoming social challenges and are functioning well in their social world (alongside neighbors, coworkers, and fellow world citizens).” | Gallagher et al. (2009, p. 1027) |

| Mental health | “a syndrome of symptoms of positive feelings and positive functioning in life” | Keyes (Reference Keyes2002, p. 207) |

| Flourishing | “high levels of wellbeing”“To be flourishing in life, individuals must exhibit a high level (high = upper tertile) on one of the two measures of emotional well-being and high levels on six of the 11 scales of positive functioning” | Hone et al. (Reference Hone, Jarden, Schofield and Duncan2014, p. 62)Keyes (Reference Keyes2002, p. 210) |

| Life satisfaction | “Life satisfaction, according to Campbell et al. (1976), reflects individuals’ perceived distance from their aspirations … satisfaction is a judgmental, long-term assessment of one’s life” | Keyes et al. (Reference Keyes, Shmotkin and Ryff2002, pp. 1007–1008) |

| Happiness | “according to Bradburn (1969), results from a balance between positive affect and negative affect … happiness is a reflection of pleasant and unpleasant affects in one’s immediate experience” | Keyes et al. (Reference Keyes, Shmotkin and Ryff2002, p. 1008) |

| Optimal wellbeing | “high subjective wellbeing and psychological wellbeing” | Keyes et al. (Reference Keyes, Shmotkin and Ryff2002, p. 1007) |

| Happiness | “In the first version of his theory, Seligman (Reference Seligman2002) claimed that ‘happiness’ was composed of three subjective facets: positive emotion, engagement, and meaning. Happiness was therefore achievable by pursuing one or more of these facets. As a result, individuals low in one aspect could still be ‘happy’ if they nurtured other components.” | Forgeard et al. (Reference Forgeard, Jayawickreme, Kern and Seligman2011, p. 96) |

| Wellbeing | “wellbeing consists of the nurturing of one or more of the five following elements: Positive emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment (abbreviated as the acronym PERMA). These five elements are the best approximation of what humans pursue for their own sake” | Forgeard et al. (Reference Forgeard, Jayawickreme, Kern and Seligman2011, p. 96) |

| Positive wellbeing | “we identified the positive pole of each symptom dimension. This resulted in ten features representing positive aspects of mental functioning: competence, emotional stability, engagement, meaning, optimism, positive emotion, positive relationship, resilience, self-esteem, and vitality … it includes both hedonic and eudaimonic components; that is, both positive feeling and positive functioning.” | Huppert and So (Reference Huppert and So2013, p. 849) |

What Is Positive Psychology?

While the origin of the term ‘positive psychology’ can be traced back to Abraham Maslow’s 1954 book, Motivation and Personality (Maslow, Reference Maslow1970; Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Lopez and Pedrotti2011), it was many years before positive psychology as an academic field was born: a vision that included steering psychology back toward what makes life worth living, toward courage, generosity, creativity, joy, gratitude (Csikszentmihalyi and Nakamura, Reference Csikszentmihalyi, Nakamura, Sheldon, Kashdan and Steger2011). The founders of positive psychology recognized that traditional psychology had become predominantly weakness-oriented: an approach that had succeeded in alleviating many forms of human suffering but had failed at capturing the whole human picture (Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Lopez and Pedrotti2011). The timing was ripe to address this imbalance issue. In the months that followed, Martin Seligman became the President of the American Psychological Association (APA), enabling him to pioneer the new field of positive psychology. He identified two “neglected missions” of psychology (Seligman, Reference Seligman1998, p. 2). The first was building human strength and making people more productive. The second was the nurturing of genius, the generation of high human potential (Compton and Hoffman, 2013; Seligman, Reference Seligman1998). Seligman saw this new field as combining scientific and applied approaches. He called for a mass of research on human strength and virtue. So 1998, therefore, marked the beginning of a seismic shift in psychology (Rusk and Waters, Reference Rusk and Waters2013b) and the birth of the field of positive psychology.

In their seminal paper, Positive Psychology: An Introduction, Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi (Reference Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi2000) outlined the purpose of the new field: the research and development of the factors that enable flourishing at individual, community and societal levels. The field’s scope included three levels of research: the subjective level, the individual level and the group level. Research at the subjective level included valued subjective experiences and was broken down into past, present and future constructs: the past involving wellbeing, contentment and satisfaction; the present involving flow and happiness; and the future involving hope and optimism. The individual level called for research into individual traits that are positive, such as character strengths (including those that guide our interactions with others), talent and the capacity for vocation. Last, the group level comprised research into “civic virtues and the institutions that move individuals towards better citizenship: responsibility, nurturance, altruism, civility, moderation, tolerance and work ethic” (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi2000, p. 5). Positive psychology thus emerged as the scientific study of positive human functioning and flourishing intrapersonally (e.g. biologically, emotionally, cognitively), interpersonally (e.g. relationally) and collectively (e.g. institutionally, culturally and globally) (Crompton and Hoffman, Reference Crompton and Hoffman2013; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, Reference Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi2000).

In the 15 or so years since the inception of positive psychology, a number of themes have surfaced, such as altruism, accomplishment, appreciation of beauty and excellence, authenticity, best possible selves, character strengths, coaching, compassion, courage, coping, creativity, curiosity, emotional intelligence, empathy, flow, forgiveness, goal setting, gratitude, grit, happiness, hope, humour, kindness, leadership, love, meaning, meditation, mindfulness, motivation, optimism, performance, perseverance, positive emotions, positive relationships, post-traumatic growth, psychological capital, purpose, resilience, savoring, self-efficacy, self-regulation, spirituality, the good life, virtues, wisdom and zest. Many of the themes studied have their origins outside of the field of positive psychology. However, Rusk and Waters (Reference Rusk and Waters2013b) looked at the breadth of the field and found that approximately a third of the positive-psychology-related terms they studied were new to the field since 1999. Therefore, it seems that positive psychology is largely exploring existing constructs, but through a fresh lens. In addition to the breadth, they also found that the size, reach and impact of the field had grown substantially since its founding. This growth has generated new sub–fields focused on the application of the science, such as positive education (Norrish Reference Norrish2015; Norrish et al., Reference Norrish, Williams, O’Connor and Robinson2013) or positive organizational behavior and positive organizational scholarship (Wright and Quick, Reference Wright and Quick2009).

As the science disseminates, there are some issues that arise by virtue of the immaturity of the field. While the breadth of research undertaken is substantial (Rusk and Waters, Reference Rusk and Waters2013b), there is tension between the depth of research and the desire for real-world application. A number of single studies have shown promising findings, but more research that replicates them across a range of populations and contexts is required: whom do interventions work for and under what conditions (i.e. effectiveness rather than efficacy: see Hone et al., Reference Hone, Jarden and Schofield2015)? More longitudinal studies are required, too. As the field matures, longitudinal studies will be conducted. In the meantime, positive psychology researchers are reminded to adhere to rigorous scientific standards (Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Lopez and Pedrotti2011) such as those of meta-analysis and randomized control trials (Vella-Brodrick, Reference Vella-Brodrick and Keyes2013). Paradoxically, while positive psychology offers itself as the antidote to the negativity bias of psychology as usual, it must not fall prey to focusing solely on the good in the world. Good science looks at the whole picture (Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, Lopez and Pedrotti2011). As the field works toward this, those working with the application of positive psychology must ensure that they are conscientious consumers of the science, and as such new journals focusing specifically on these issues are emerging (e.g. the International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, which will launch in 2016). It is with this in mind that we move to the key theories and evidence.

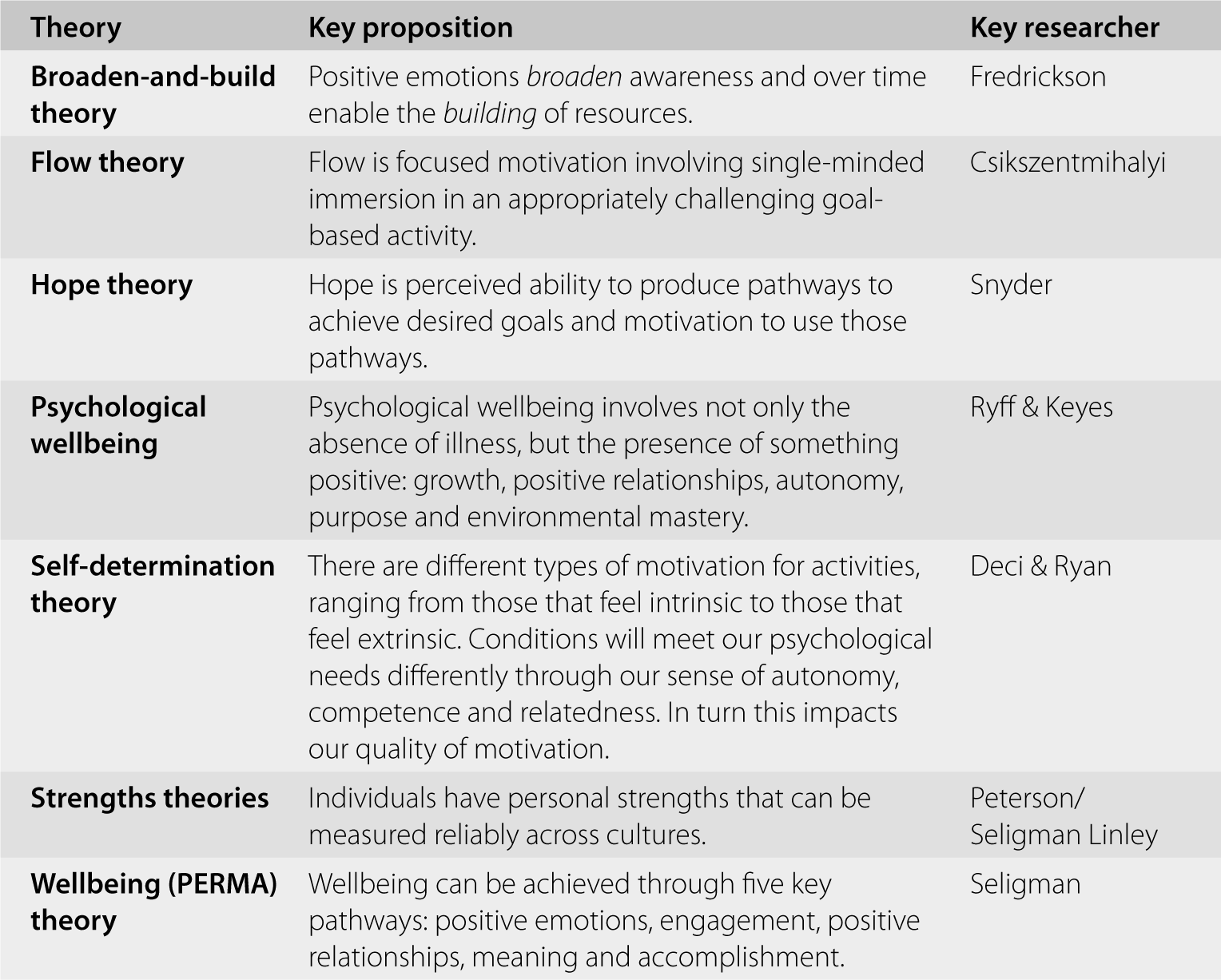

What Are Some Key Theories within Wellbeing and Positive Psychology Research?

There is a well-established suite of theories relating to wellbeing and key areas of positive psychology. Table 2.2 provides a sample of some of the key theories, which include emotions, attentional states, cognition, motivation, goal striving and relationships.

| Theory | Key proposition | Key researcher |

|---|---|---|

| Broaden-and-build theory | Positive emotions broaden awareness and over time enable the building of resources. | Fredrickson |

| Flow theory | Flow is focused motivation involving single-minded immersion in an appropriately challenging goal-based activity. | Csikszentmihalyi |

| Hope theory | Hope is perceived ability to produce pathways to achieve desired goals and motivation to use those pathways. | Snyder |

| Psychological wellbeing | Psychological wellbeing involves not only the absence of illness, but the presence of something positive: growth, positive relationships, autonomy, purpose and environmental mastery. | Ryff & Keyes |

| Self-determination theory | There are different types of motivation for activities, ranging from those that feel intrinsic to those that feel extrinsic. Conditions will meet our psychological needs differently through our sense of autonomy, competence and relatedness. In turn this impacts our quality of motivation. | Deci & Ryan |

| Strengths theories | Individuals have personal strengths that can be measured reliably across cultures. | Peterson/Seligman Linley |

| Wellbeing (PERMA) theory | Wellbeing can be achieved through five key pathways: positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, meaning and accomplishment. | Seligman |

What Is the Evidence Base?

The evidence base underpinning the field of positive psychology is small but rapidly growing (Rusk and Waters, Reference Rusk and Waters2013) and can be broken down into cross-sectional studies and causal studies. Cross-sectional studies look at associations between variables (e.g. are happier people healthier?), and causal studies look at what impacts wellbeing over time (i.e. does marriage increase wellbeing?). Both types of studies can lead to inferences about what leads to or predicts wellbeing, with causal studies providing strong evidence.

As an example of a cross-sectional study, Waugh and Fredrickson (Reference Waugh and Fredrickson2006) found that in a group of students increased assimilation and understanding of their roommates was associated with higher levels of positive emotion. The caution with these types of cross-sectional studies is that it is not clear or conclusive if A leads to B, of if B leads to A, or if some other variable mediates the relationship – for example, if higher positive emotion leads to greater understanding of roommates, or if greater understanding of roommates leads to higher positive emotion. As some further examples of this type of research, Fredrickson and Levenson (Reference Fredrickson and Levenson1998) found that positive emotions can help people cope with physiological responses to negative emotions, and in a large meta-analysis, Lyubomirsky et al. (Reference Lyubomirsky, King and Diener2005) found that people with higher levels of positive emotion were more successful across many life domains such as work, relationships and health.

As an example of a causal study, Lyubomirsky et al. (Reference Lyubomirsky, King and Diener2005) examined the results of experimental studies and found that increasing people’s positive emotions had the effect of making them better at conflict resolution and more social. They also found in their meta-analysis, which included longitudinal studies, that happiness does lead to better relationship and work outcomes. As examples of evidence they cited findings that increases in happiness lead to greater creativity, productivity and quality of work, and income (Estrada et al., Reference Estrada, Isen and Young1994) and to stronger social support and an increased likelihood of marriage (Harker and Keltner, Reference Harker and Keltner2001), that subjective wellbeing impacts mental and physical health (Pressman and Cohen, Reference Pressman and Cohen2005) and leads to healthier immune function (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Kabat-Zinn, Schumacker, Rosenkranz, Muller and Sontorelli2003), and that happier people even live longer.

Furthermore, what both this cross-sectional and causal research suggest is that positive emotions can and do have impacts beyond individuals to their close connections.

What Is the Evidence for Positive Psychology Interventions?

Sin and Lyubomirsky (Reference Sin and Lyubomirsky2009) define positive psychology interventions (PPIs) as “treatment methods or intentional activities aimed at cultivating positive feelings, positive behaviours, or positive cognitions.” Their meta-analysis found that PPIs are effective at increasing wellbeing and decreasing depression, but the effect sizes were moderate and should be treated with a level of caution. They found four factors that heighten the efficacy of PPIs: high levels of depression; increased age; individual interventions (rather than group interventions); and longer interventions. There is some debate as to whether participants should be matched to interventions based on a person–activity fit or not. For example, participant preference for undertaking a PPI has been positively related to commitment to adhere to the activity (Schueller, 2010), and matching participants to an intervention that was based on an orientation to happiness that differed from their dominant orientation was effective at enhancing wellbeing (Giannopoulos and Vella-Brodrick, Reference Giannopoulos and Vella-Brodrick2011).

However, Schueller (2011) found no significant difference between participants assigned to activities based on preference and those randomly assigned to activities. PPIs have been used in studies specifically targeting clinical participants, such as positive psychotherapy (PPT; Seligman et al., Reference Seligman, Rashid and Parks2006; see Chapter 11) and in nonclinical studies. However, regardless of the population, many study designs include pre- and post-test measures of depression and/or negative affect as well as measures of positive functioning.

Typically, studies include a broader range of measures, such as stress (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Tsu and Lam2015); state and trait anxiety (Cheavens et al., Reference Cheavens, Feldman, Gum, Scott and Snyder2006); ruminative thinking (Odou and Brinker, Reference Odou and Brinker2014a); self-esteem (Sergeant and Mongrain, Reference Sergeant and Mongrain2011); Big Five personality (Huppert and Johnson, Reference Huppert and Johnson2010); working memory capacity (Jha et al., Reference Jha, Stanley, Kiyonaga, Wong and Gelfand2010); physical symptoms (Emmons and McCullough, Reference Emmons and McCullough2003; Sergeant and Mongrain, Reference Sergeant and Mongrain2011); and self-compassion (Odou and Brinker, Reference Odou and Brinker2014a, Reference Odou and Brinker2014b).

Table 2.3 includes examples of the efficacy of PPIs. It should be noted that many constructs explored in PPIs have their origins outside positive psychology, such as gratitude, forgiveness and mindfulness. While positive psychology cannot lay claim to these concepts, its role does include an understanding of their function in building human strength and generating high human potential.

| Intervention | Efficacy | Participants | Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best possible selves (BPS; including you at your best) | You at your best led to gains in happiness and decreased depression immediately postintervention (Seligman et al., Reference Seligman, Steen, Park and Peterson2005). | Adults (range = 35–54 years) recruited via the Internet | Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale(CES-D) symptom survey; 20-item Steen Happiness Index (SHI) |

| (involves writing about oneself at one’s best in all domains of one’s life) | BPS has been shown to lead to greater increases in positive affect and self-concordant motivation as compared with counting blessings and control groups. It has also led to immediate decreases in negative affect (Sheldon and Lyubomirsky, Reference Sheldon and Lyubomirsky2006). | University students | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS); Self-Concordant Motivation (SCM); exercise performance, for example, how frequently exercise was practiced |

| The BPS condition was found to be more effective at increasing optimism than the control condition (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Flink, Boersma and Linton2010). | Swedish university students (mean age = 29.6 years, range 21–50) | Dispositional optimism, the Life Orientation Test (LOT); extraversion and neuroticism measured by two subscales of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised Short Scale (EPQ-RSS); short form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) | |

| Forgiveness | Forgiveness interventions have been used with a broad range of clinical clients, with foundational research occurring before positive psychology. Combined with gratitude and life memories in an intervention, forgiveness has been found to help increase subjective well-being and quality of life (Ramírez et al., Reference Ramírez, Ortega, Chamorro and Colmenero2014). | Older adults (mean = 71.18 years; range 60–93 years) | Spanish versions of the State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI); Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); Autobiographical Memory Test (AMT); Mini-cognitive Exam (Mini-Examen Cognoscitivo [MEC]; Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS); Subjective Happiness Scale |

| Gratitude | Gratitude visits have been shown to lead to gains in happiness and decreased depression in adults immediately postintervention and up to 1 month postintervention (Seligman et al., Reference Seligman, Steen, Park and Peterson2005). | Adults (range = 35–54 years) recruited via the Internet | Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale(CES-D) symptom survey; 20-item Steen Happiness Index (SHI) |

| (including gratitude visit; gratitude letters; noticing good things; recording good things; counting blessings) | Youth low in positive affect have reported high levels of gratitude (compared to the control group) and positive affect immediately after the gratitude letter/journal intervention, and positive affect at 2 months’ follow-up (Froh et al., Reference Froh, Kashdan, Ozimkowsk and Miller2009). | Students (mean age = 12.74 years, range = 8 –19 years) | Gratitude Adjective Checklist (GAC); Positive and Negative Affect Scale – Children (PANAS-C) |

| Counting blessings participants in the gratitude condition have reported improved wellbeing as measured by optimistic appraisal of life, increased exercise, decreased reporting of physical symptoms and increased positive affect (Emmons and McCullough, Reference Emmons and McCullough2003). | Undergraduate students plus adults with either congenital or adult-onset neuromuscular disease (mean age = 49 years, range = 22–77 years) | A weekly form included ratings of mood, physical symptoms, reactions to social support received, estimated amount of time spent exercising, and two global life appraisal questions | |

| Counting blessings has also been shown to lead to immediate decreases in negative affect (Sheldon and Lyubomirsky, Reference Sheldon and Lyubomirsky2006). | University students | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS); Self-Concordant Motivation (SCM); exercise performance, for example, how frequently exercise was practiced | |

| In a double-blind randomized controlled trial Cheng et al. (Reference Cheng, Tsu and Lam2015) found lower depressive symptoms and a reduction in perceived stress for a gratitude condition. | Full-time Chinese professional healthcare practitioners | Chinese version of the 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D); Chinese version of the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale | |

| Kerr et al. (Reference Kerr, O’Donovan and Pepping2015) reliably cultivated the emotional experience of gratitude in a two-week intervention with a clinical sample on a waiting list for outpatient psychological treatment. | Adults (mean age = 43 years, range 19–67) seeking individual psychological treatment. | Participants rated intensity of gratitude or kindness felt; a version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; the Purpose in Life test (PIL); Outcome Questionnaire-45.2 (OQ-45); the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21). Participants also rated how connected they felt with others. | |

| Three good things led to gains in happiness and decreased depression immediately postintervention as well as increases for up to 6 months postintervention in comparison with the placebo control group (Seligman et al., Reference Seligman, Steen, Park and Peterson2005). Some researchers may consider three good things as savoring rather than gratitude. | Adults (range = 35–54 years) recruited via the Internet | Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale(CES-D) symptom survey; 20-item Steen Happiness Index (SHI) | |

| Sergeant and Mongrain (Reference Sergeant and Mongrain2011) found that a gratitude condition where participants identify five good things over the course of a day led to increased reported happiness over time in comparison to the control group. Self-critics reported the most favorable outcomes if they were assigned to the gratitude condition. Needy individuals did not benefit from the intervention and even decreased with regards to self-esteem (Sergeant and Mongrain, Reference Sergeant and Mongrain2011). | Volunteer adults (mean age = 34 years, range = 18–72 years) | Centre for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale, Depressive Experiences Questionnaire, Gratitude Questionnaire-6, measure of physical symptoms, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Steen Happiness Index | |

| Hope | Hope interventions have led to improvements from pre to postintervention for agency hope (but not pathways hope), anxiety, self-esteem and purpose in life (Cheavens et al., Reference Cheavens, Feldman, Gum, Scott and Snyder2006). | Adults recruited from the community through advertisements in the local newspaper (mean age = 49 years old, range = 32–64) | The State Hope Scale; Center for Epidemiologie Studies – Depression Scale (CES-D); State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Form Y; Index of Self-Esteem (ISE); Purpose In Life Test (PIL) |

| Mindfulness(defined as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment“ (Kabat-Zinn, Reference Kabat-Zinn2003, p. 2) | Huppert and Johnson (Reference Huppert and Johnson2010) found a positive relationship between the amount of time adolescent boys spent practicing mindfulness and improvements in both psychological wellbeing and mindfulness. | Adolescent boys (range 14–15 years). | Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale – Revised (CAMS-R); Ego-Resiliency Scale (ERS); Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS); Big Five personality dimensions were measured using the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI). At follow-up, participants in the mindfulness condition were also asked a series of questions such as the number of times they had practiced mindfulness outside of class, how helpful they found it and whether they thought they would continue to practice mindfulness. |

| Jha et al. (Reference Jha, Stanley, Kiyonaga, Wong and Gelfand2010) found improvements in positive affect for participants with higher levels of mindfulness training. Due to limitations of sampling, this was not a randomized study design. | Adult participants included three groups: military control (MC) group; civilian control (CC) group; mindfulness and mindfulness training group (MT) | The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). Working memory capacity (WMC) was also tested through an automated test. | |

| Music (listening to three or four uplifting songs of participant’s choosing each day) | Participants reported greater increases in happiness over time than the control group (Sergeant and Mongrain, Reference Sergeant and Mongrain2011). | Volunteer adults (mean age = 34 years, range = 18–72 years) | Centre for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale, Depressive Experiences Questionnaire, Gratitude Questionnaire-6, measure of physical symptoms, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Steen Happiness Index |

| Positive psychotherapy (PPT)(includes a combination of gratitude visit, three good things in life, you at your best, using signature strengths in a new way, identifying signature strengths) | Seligman et al. (Reference Seligman, Rashid and Parks2006) tested the efficacy of PPT in two studies. In the first study, PPT was delivered to groups of university students with mild to moderate depression. This significantly decreased levels of depression through 1-year follow-up as compared with the control group. In the second study, PPT delivered to outpatients with unipolar depression produced higher remission rates than did treatment as usual or treatment as usual plus medication. The findings of these studies suggest that exercises that explicitly increase positive emotion, engagement and meaning may be useful in treating depression. | Study One: mild to moderate depressive symptoms. Study Two: major depressive disorder (MDD; unipolar depression). | Study One: Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI); Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS); Study Two: Zung Self-Rating Scale (ZSRS); Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD); Outcome Questionnaire (OQ); DSM–IV’s Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). Happiness and wellbeing were assessed using and by the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) and the Positive Psychotherapy Inventory (PPTI), a 21-item PPT outcome measure created and validated by the study researchers. |

| Savoring (savoring can be past-focused (reminiscing about positive experiences), present-focused (savoring the moment) or future-focused (anticipating positive experiences yet to come) (Smith et al., 2014) | Preference for undertaking PPI is positively related to adherence to the activity. The savoring exercise produced statistically significant increases in happiness and decreases in depression. Those who preferred active constructive responding also preferred savoring (Schueller, 2010). | Participants were visitors to a university research Internet portal. 329 were assigned to savoring (average age = 53.5). | The Authentic Happiness Inventory (AHI); the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) |

| Self-compassionate writing | Negative mood induced. Randomly allocated to write about a negative event in either a self-compassionate or an emotionally expressive way. Self-compassionate writing has been shown to significantly predict improved mood compared with the control group (Odou and Brinker, Reference Odou and Brinker2014a). | Undergraduate (mostly first-year) psychology students (mean age = 20.9, range = 17– 59): 3.7% reported a past diagnosis, and 3.7% reported a current diagnosis of depression. | The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS); Ruminative Thought Style Scale (RTS); Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS); 100mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) |

| Participants writing self-compassionately experienced increased positive affect and reduced negative affect; high ruminators experienced greater reduction of sadness than low ruminators (Odou and Brinker, Reference Odou and Brinker2014b). | Undergraduate students (mean = 21.3, range = 17–57 years): 14% of participants had a past diagnosis of depression while 2% reported having a current diagnosis. | The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS); Ruminative Thought Style Scale (RTS); The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS); 100mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). |

Conclusion

In this chapter we introduced key definitions relating to wellbeing and highlighted ways to approach this contested domain. After a summary of some key theories within the science of wellbeing and positive psychology, a brief overview of recent empirical evidence for positive psychology interventions (PPIs) was provided. Key debates continue about evidence from clinical compared with nonclinical populations, adding emphasis to the usefulness of cross- [?] fertilization between wellbeing research and research in mental health recovery.