1 Introduction

The IPA provides a variety of diacritics which can be added to base symbols in various positions: above ([ã]), below ([n̥]), through ([ɫ]), superscript after ([tʰ]) or centered after [(a̴)]. Currently, IPA diacritics which modify base symbols are never shown preceding them; the only diacritics which precede are the stress marks, i.e. primary ([ˈ]) and secondary ([ˌ]) stress. Yet, in practice, superscript diacritics are often used preceding base symbols; specifically, they are often used to notate prenasalization, preglottalization and preaspiration. These terms are very common in phonetics and phonology, each having thousands of Google hits. However, none of these phonetic phenomena is included on the IPA chart or mentioned in Part I of the Handbook of the International Phonetic Association (IPA 1999), and thus there is currently no guidance given to users about transcribing them. In this note we review these phenomena, and propose that the Association’s alphabet include superscript diacritics preceding the base symbol for prenasalization, preglottalization and preaspiration, in accord with one common way of transcribing them.

Given that the IPA chart does not exemplify these phenomena, it is unsurprising that current usage is varied. For example, while most textbooks do not mention these phenomena, in those textbooks and reference works that do cover them, each offers a different possible notation. In the case of preaspiration, the extended IPA of the International Clinical Phonetics and Linguistics Association (in the Handbook) does specify a notation with a preceding superscript diacritic, e.g.[ʰp], and Ball & Rahilly’s (Reference Ball and Rahilly1999: 73–74) textbook presents this. Ashby (Reference Ashby2011: 128-129) uses a similar diacritic for allophonic preglottalization, e.g. [ʔt], and Laver (Reference Laver1994) notates all three phenomena with a preceding superscript diacritic.Footnote 1 On the other hand, some textbooks (Ladefoged Reference Ladefoged1975 and later editions; Catford Reference Catford1988: 114; Rogers Reference Rogers2000: 224) transcribe prenasalization as a sequence of two symbols, e.g. [nd].Footnote 2 Rogers (Reference Rogers2000: 55) also uses a sequence of symbols for preglottalization, but adding a tie bar, e.g. [ʔ͡t]. Similarly, Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 74, figure legend): 74, figure legend) show a sequence with a tie bar for allophonic (pre)glottalization, but without a tie bar for preaspiration and prenasalization.

Likewise, various research articles published in the Journal of the International Phonetic Association and elsewhere exhibit these transcription options. Most strikingly, this is true of the Illustrations of the IPA of languages with these sounds published in the Handbook and in JIPA since 2001. Table 1 summarizes the practice of these Illustrations. For example, four Illustrations mention preglottalization. Carlson, Esling & Fraser (Reference Carlson, Esling and Fraser2001) on Nuuchahnulth, Anonby (Reference Anonby2006) on Mambay,Footnote 3 and DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010) on Itunyoso Trique all use a preceding superscript, e.g. [ʔm], while Baird (Reference Baird2002) on Keo uses a sequence beginning with a full glottal stop, e.g. [ʔb]. Presentations of prenasalization are the most varied, and the most common, with the superscript diacritic in the minority. In contrast, preaspiration is rare in Illustrations, but both presentations use the superscript diacritic. It is noteworthy that none of these Illustrations mentions that these phenomena do not appear in the IPA’s presentations of its symbols.Footnote 4

Table 1: Transcription of prenasalization/preaspiration/preglottalization in JIPA, 2001–2017, and in Illustrations of the IPA published in the Handbook of the IPA (IPA 1999).

Research articles in JIPA and elsewhere show a similar variety. For preaspiration, there is a clear preference for the superscript diacritic (Helgason Reference Helgason2002 on Nordic languages, Silverman Reference Silverman2003 on many languages, Hoole & Bombien Reference Hoole, Bombien, Fuchs, Hoole, Mooshammer and Żygis2010 on Icelandic, Karlsson & Svantesson Reference Karlsson and Svantesson2011 on Mongolian, Clayton Reference Clayton2017 on Hebrides English), though Gordon (Reference Gordon1996) uses a sequence for Hupa (also see below for other uses of sequences). For prenasalization, sequence notation is common (Stanton Reference Stanton2015), but when specifying that a single segment is involved, superscripts are seen (Cohn & Riehl Reference Cohn, Riehl, Butler and Renwick2012, Ratliff Reference Ratliff, Enfield and Comrie2015). For preglottalization, sequences are common (Roengpitya (Reference Roengpitya1997) on Lai, Keller (Reference Keller2001) on Brao-Krung; Roach (Reference Roach1973) and MacMahon (Reference MacMahon, Aarts and McMahon2006) for English), but Esling and his colleagues generally use a superscript, e.g. Carlson et al. (Reference Carlson, Esling and Fraser2001) on Nuuchahnulth (exceptions include Edmondson et al. (Reference Edmondson, Esling, Harris and Wei2004), who use a sequence, and Esling, Fraser & Harris (Reference Esling, Fraser and Harris2005), who use a superscript with a tie bar for English).

Thus we find ourselves in a situation where many researchers need to refer to these phenomena, but the IPA offers no guidance. The current proliferation of transcription practices, even in our own Journal, is the result. In what follows, we review the literature on the phonetics and phonology of prenasalization/preglottalization/preaspiration, showing that these phonetic phenomena are sufficiently well-established to merit a fixed, dedicated IPA representation.

2 Literature on the phonetics and phonology of these phenomena

In this section we summarize phonetic evidence that in prenasalization/preglottalization/ preaspiration, the interval of nasalization/glottalization/aspiration comes first, and that it can form part of a single complex phonetic segment, with a single primary oral constriction, rather than a two-segment cluster. We then report on phonological evidence that the prenasalized, preglottalized or preaspirated segments can pattern like single segments rather than like clusters, and can contrast with phonetically similar segments within a language. Thus, although there is a sequence of phonetic events, it is considered to be a single segment phonetically and/or phonologically. Throughout, we retain the original authors’ transcriptions.

2.1 Prenasalization

Prenasalization is generally defined as a nasal–oral sequence which is often homorganic and which functions as a single unit, often with reference to its occurrence as a syllable onset (e.g. Catford Reference Catford1988, Ladefoged & Maddieson Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996). Maddieson & Ladefoged (Reference Maddieson, Ladefoged, Huffman and Krakow1993:254) report that about 12% of the languages in UPSID (Maddieson Reference Maddieson1984) contain prenasalized phonemes, making prenasalization the most common of the three phenomena treated in our proposal. (In contrast, nasal release occurs in only one language in UPSID.) A bibliography of some 50 languages with prenasalized consonants is given as an appendix in Stanton (Reference Stanton2015), which also cites previous cross-language studies. Ratliff (Reference Ratliff, Enfield and Comrie2015) surveys the incidence of prenasalization in Mainland South East Asian languages.

2.1.1 Phonetics

It is uncontroversial that in prenasalized sounds, a nasal interval comes before an oral interval: the velum is first lowered, then raised (e.g. Burton, Blumstein & Stevens (Reference Burton, Blumstein and Stevens1992), Beddor & Onsuwan (Reference Beddor and Onsuwan2003), Riehl (Reference Riehl2008); see Stanton (Reference Stanton2015) for additional references). Cohn & Riehl (Reference Cohn, Riehl, Butler and Renwick2012) noted that in many Austronesian languages, vowels after prenasalized consonants are oral, while after nasals, vowels are nasalized; that is, the right edge of a prenasalized consonant is fully oral.

More controversial is whether they are unitary, though complex, segments. Herbert (Reference Herbert1976) suggested that prenasalized segments should have the phonetic duration of a single segment, else they should be considered clusters of two segments. Studies of several languages have presented this kind of argument; see Stanton (Reference Stanton2015) for a summary of this literature, and also Avram (Reference Avram2010), Rivera-Castillo (Reference Rivera-Castillo2013). For example, Maddieson (Reference Maddieson1989) shows that Fijian prenasalized consonant durations match those of voiceless stops and /l/, and durations of vowels before the various consonants are likewise similar.

Nonetheless, it is clear that languages differ in the relative durations of their prenasalized segments; for example, Cohn & Riehl (Reference Cohn, Riehl, Butler and Renwick2012) examined NC (nasal consonant–oral consonant) sequences in six Austronesian languages, some already thought to be clusters, and others of unknown status. They found three different duration patterns, one of which was clearly compatible with a unitary segment. Henton, Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Henton, Ladefoged and Maddieson1992)/Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996) discuss the problems with duration-based arguments, but it seems that in some languages, though certainly not all, prenasalized segments do have the durations of single segments.

2.1.2 Phonology

Regardless of whether prenasalized consonants have durations that mark them as likely single segments, they are often analyzed as single phonological segments. Indeed, status as single phonological segments is part of the definition of prenasalized consonants given by Catford (Reference Catford1988), Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996), and Riehl (Reference Riehl2008). Several kinds of arguments for such analyses are seen in the literature (see e.g. Feinstein Reference Feinstein1979 for discussion). The first – and by far the most commonly offered – is that prenasalized consonants have the distribution of single segments. This can be especially clear in languages without clusters or coda consonants. For example, Maddieson (Reference Maddieson1989) cites Geraghty’s (Reference Geraghty1983) unitary analysis of Fijian prenasalization. In Fijian, there are no (other) consonant sequences – no onset clusters, no coda consonants. If prenasalized consonants were treated as sequences, they would be the only instances of onset clusters or coda consonants in the language. Keenan & Chung (Reference Keenan and Chung2017) have recently made the same argument in favor of prenasalized segments in Malagasy. As Stanton (Reference Stanton2015) notes, given a choice of complicating the inventory or the phonotactics of a language, analysts will mostly choose to add to the inventory. Similarly, it is often pointed out that prenasalized consonants can occur initially, where they are unlikely clusters given their decreasing sonority (though cf. Riehl Reference Riehl2008: Section 1.3). In some languages, e.g. Nara (Illustration of the IPA by Dawd & Hayward Reference Dawd and Hayward2002), the prenasalized plosives occur only in onset position. Nonetheless, exceptions are found. Tataltepec Chatino (Sullivant Reference Sullivant2015) has initial phonetic prenasalized voiced stops which, unlike nasal stops, do not bear tone. They would thus seem to be units, and analyzing them as NC sequences complicates the phonotactics of the language. However, Sullivant analyses them as exceptional sequences on the basis of morphology: the nasal portion is a separate morpheme which word-internally appears as a full nasal stop. When this morpheme appears before a word-initial oral stop (which in this language are all voiceless), a general pattern of post-nasal voicing creates a phonetic prenasalized voiced stop.

Another kind of argument is that prenasalized consonants contrast with NC sequences, and thus cannot be analyzed as sequences. As Laver (Reference Laver1994: 229) says: ‘it would be persuasive if languages could be found where words are contrastively identified by means of these complex stops versus comparable sequences of their simple nasal and oral stop counterparts’. However, the cases of this kind cited by Laver do not involve simple NC sequences like [mb]; rather, they involve either NːC sequences with long nasals (e.g. Sinhalese, Sinhalese, Jones Reference Jones1950: 79–81, cited by Laver) or NˌC sequences with syllabic nasals (e.g. Nyanja, Nyanja, Herbert Reference Herbert1986: 161; Tiv, Arnott 1969; another such case is Swahili adjective forms (Hinnebusch & Mirza Reference Hinnebusch and Mirza1998, cited by Mwita Reference Mwita2007)). For example, Arnott shows that in word-initial position Tiv contrasts prenasalized stops with plain voiced and voiceless stops, and with nasals and syllabic (tone-bearing) nasals – e.g. /mbàrá/ contrasts with /pá/, /báŕ/, /mátó/ and /ḿ-kèḿ/. The syllabic (tone-bearing) nasals are distinct from the prenasalized consonants.

(1) Tohoku Tokyo English gloss

Those Japanese dialects with both prenasalized stops and NC sequences perhaps make a more compelling case. In some north-eastern (Tohoku) dialects of modern Japanese, prenasalized intervocalic consonants are attested; they are thought to have been preserved from Old Japanese (Vance, Miyashita & Irwin Reference Vance, Miyashita, Irwin, Nam, Ko and Jun2014). These prenasalized consonants contrast with NC sequences and with Nː (examples from Yu Tanaka, p.c.), as seen in (1). It is possible that the moraic status of nasal consonants enhances this contrast; certainly this case merits further study.

On the other hand, something of the opposite argument from inventory gaps is sometimes made for unitary status. For example, Riehl (Reference Riehl2008) takes the absence of plain nasals and/or plain voiced stops as the clearest evidence for the unitary status of prenasalized stops. The idea is that if a language lacks, e.g. /n/ and/or /d/, then [nd] cannot be the result of their concatentation. Cases of this kind in addition to Fijian include Kikongo (Welmers Reference Welmers1973, cited by Mwita Reference Mwita2007), San Miguel el Grande Mixtec (Iverson & Salmons Reference Iverson and Salmons1996), and Tamabo (Riehl & Jauncey’s Reference Riehl and Jauncey2005 Illustration of the IPA). In Tamabo the only voiced plosives are prenasalized (though plain nasals occur); Riehl (Reference Riehl2008) notes that this is a common pattern in Oceanic languages, mentioning other languages with this distribution. Mixtec languages also show this pattern. Nonetheless, inventories with gaps appear to be less common than ones where prenasalized stops contrast with other stops (oral and nasal) (as can be seen in Appendix A in Stanton Reference Stanton2015, where examples of inventories without gaps include Gbeya (Samarin Reference Samarin1966) and Makaa (Heath Reference Heath, Nurse and Philippson2003)).

More generally, prenasalized stops are often language-specific variants of voiced stop phonemes, with prenasalization aiding in the initiation and maintenance of voicing in stops (see e.g. see e.g. Rothenberg Reference Rothenberg1968). Examples of prenasalized consonants alternating with voiced stops include Taiwanese Taiwanese (Pan Reference Pan1994, Hsu & Jun Reference Hsu and Jun1998) and Greek (Arvaniti Reference Arvaniti1999, Arvaniti & Joseph Reference Arvaniti and Joseph2000). Solé (Reference Solé2014) describes low-level but perceptible prenasalization in Spanish voiced stops. Conversely, as already seen for Japanese, voiced consonants can be reflexes of historical prenasalized consonants. Ratliff (Reference Ratliff, Enfield and Comrie2015) describes the various historical developments of original prenasalized consonants in the languages of Mainland South East Asia, noting that across languages these consonants are now variably NˌC, NC, NC, NC or plain voiced C. Overall, then, there is a possible argument from correspondences: prenasalized consonants often correspond to voiced stops, which are clearly unitary segments. Similarly, they may correspond to nasal stops: DiCanio et al. (Reference DiCanio, Zhang, Whalen and García2018) describe an alternation in Yoloxóchitl Mixtec where NC is an allophone of N before oral vowels. Since N is a unit, its allophone NC is considered a unit as well.

In sum, prenasalized consonants in at least some languages behave phonetically and/or phonologically like single segments rather than like sequences, with nasalization preceding an oral interval, and they can contrast with nasals and/or voiced stops.

2.2 Preaspiration

Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 70) define preaspiration as ‘a period of voicelessness at the end of the vowel, nasal or liquid preceding the onset of the stop closure’; similarly, Laver (Reference Laver1994: 356), ‘early offset of normal voicing in the syllable-nuclear voiced segment, anticipating the voicelessness of the syllable-final voiceless segment’. Helgason (Reference Helgason2002: iii) gives a slightly different definition that stresses the noise component of preaspiration: ‘glottal friction at the juncture of a vowel and a consonant’. All of these definitions call attention to the necessity of a sonorant sound (often a vowel) before the preaspirated consonant.

Preaspiration is relatively rare in languages, with ‘2 UPSID languages, perhaps two dozen or so confirmed examples worldwide’ (Clayton Reference Clayton2010: 1);Footnote 5 see also Hejná (Reference Hejná2015), Clayton (Reference Clayton2017). Postaspiration, in contrast, occurs in 26% of UPSID languages. Most of the discussion of preaspiration in the literature has centered on Nordic and other languages of northern Europe (Icelandic, Faroese, Swedish, Gaelic, Sámi), but it occurs elsewhere as well (see e.g. Silverman Reference Silverman2003 and Clayton Reference Clayton2017 for surveys). Silverman (Reference Silverman2003) shows that what is called preaspiration is often something perceptually more salient, e.g. oral frication; here we will ignore this distinction.

2.2.1 Phonetics

While preaspirated fricatives occur (Hejná Reference Hejná2015), stops are more common and we focus on those here. It is commonly argued that preaspirated stops are sequences of two phonetic segments, [h] plus a stop. Hoole & Bombien (Reference Hoole, Bombien, Fuchs, Hoole, Mooshammer and Żygis2010), Clayton (Reference Clayton2010) and Hejná (Reference Hejná2015), among others, review some arguments for this position: that the duration of the aspiration component is as great as the stop closure component, i.e. about two segments’ total duration; that the phonetic properties, including duration and articulator gestures, of the aspiration component are like segmental [h]; and that the duration of the aspiration component is noticeably greater than the duration of postaspiration, so that the single-segment status of postaspirated stops does not carry over to preaspirated stops. Hoole & Bombien present evidence from Icelandic against the first two of these arguments: in their study, preaspiration was shorter than oral closure, and had different articulatory properties than [h]. NíChasaide (Reference NíChasaide1985) and Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996) presented similar duration results from Lewis Gaelic; indeed, Nance & Stuart-Smith (Reference Nance and Stuart-Smith2013) found systematic speaker variation, with younger Lewis speakers having even shorter preaspiration than older speakers. Thus, preaspiration can be shorter than an [h] segment and thus a preaspirated stop can be shorter than two segments.

With respect to comparisons of pre- and postaspiration, NíChasaide (Reference NíChasaide1985) showed that while preaspiration is generally longer than postaspiration, preaspiration duration is so variable that in some languages/contexts the reverse is true (with the durations of preaspiration and postaspiration inversely correlated). Recently, Nance & Stuart-Smith (Reference Nance and Stuart-Smith2013) showed just this pattern in Lewis Gaelic (see also Clayton Reference Clayton2010). While it is safe to say that the issue remains unsettled, the weight of recent phonetic evidence seems against the two-segments interpretation.

2.2.2 Phonology

The phonological status of preaspirated consonants as single vs. complex segments is mixed across languages. One argument for phonological unit segments is the common correspondence between preaspirated and postaspirated stops within a language. As Helgason (Reference Helgason2002), Silverman (Reference Silverman2003), Clayton (Reference Clayton2010: 63–65) and Nance & Stuart-Smith (Reference Nance and Stuart-Smith2013), among others, discuss, in many languages preaspirated consonants are positional allophones of an aspirated series. Preaspirated stops typically occur in medial and final positions, while postaspirated stops typically occur in initial position. Examples reviewed by Clayton include not only the Germanic languages and Gaelic, but also Halh Mongolian, Tarascan, Bora, and O’odham (where word-initial stops alternate depending on phrasal position). Since postaspirated stops are uncontroversially single segments, preaspirated stops must be too. Similarly, DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2012) describes preaspiration as a correlate of the fortis stops of Itunyoso Triqui, which are uncontroversially single segments.

A more delicate argument (e.g. NíChasaide Reference NíChasaide1985) comes from the fact that, as noted above, when a preaspirated stop follows a sonorant consonant, the sonorant is devoiced; there is no separate /h/ interval between the sonorant and the stop closure.

Finally, some languages exhibit morphophonemic alternations between unaspirated and preaspirated phonemes – alternations that, if the preaspirated consonants are not single segments, would require /h/ infixation in contexts where otherwise infixation is not posited (NíChasaide Reference NíChasaide1985, citing e.g. Árnason Reference Árnason1980).

On the other hand, in favor of /hC/ sequence analyses is the fact that preaspirates often pattern like (indeed, often derive from) geminates or CC sequences. (For a recent example, see Stevens & Reubold Reference Stevens and Reubold2014.) Their distribution, favoring medial and final positions, is typical of geminates. One could argue that if geminates are sequences, then so are the corresponding preaspirates. In some languages, [h] now freely occurs before a variety of consonants as a result of phonological change, e.g. Spanish dialects with coda /s/ lenition (e.g. Lipski Reference Lipski1984, Reference Lipski1994; Torreira Reference Torreira2012), and Mazatec (Ladefoged & Maddieson Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996). Although the term preaspiration is often used for the resulting occurrences, most authors seem to agree that these are phonological sequences. A final argument for sequence status is that preaspirated stops never contrast completely minimally with either postaspirates or with CC sequences.

In sum, preaspirated consonants in at least some languages behave phonetically and/or phonologically more like single segments than like sequences, with aspiration preceding an oral closure. They generally do not contrast with, but instead are allophones of, postaspirated consonants.

2.3 Preglottalization

As Henton et al. (Reference Henton, Ladefoged and Maddieson1992) note, the term ‘glottalized’ is ambiguous in the literature,Footnote 6 meaning either ‘[using the vocal cords] as an airstream initiator, as in glottalic ejectives’ or ‘preceded or followed by a glottal stop’. Here we exclude the glottalic meaning from consideration. Esling et al. (Reference Esling, Fraser and Harris2005: 389) define a preglottalized consonant simply as one which is ‘preceded by a glottal stop’. However, our usage here is perhaps broader, including laryngeal constrictions which do not produce a full occlusion (though they might be perceived as such).

In UPSID, 9% of the languages have ‘laryngealization’, which includes any preceding or simultaneous glottal stop or constriction in nonglottalic sonorants and obstruents. By comparison, 15% of UPSID languages have ejective stops.

2.3.1 Phonetics

Ladefoged & Maddieson (Reference Ladefoged and Maddieson1996: 55) usefully distinguish two dimensions along which glottalized consonants can vary. First, the glottalization (glottal constriction) itself can vary from ‘modified voicing’ (e.g. creaky voice) to a full glottal stop.Footnote 7 Realizations along this continuum are influenced by such factors as speech rate and style (e.g. Redi & Shattuck-Hufnagel Reference Redi and Shattuck-Hufnagel2001, Pompino-Marschall & Żygis Reference Pompino-Marschall and Żygis2010) and prosody (e.g. Garellek Reference Garellek2014). Second, the timing of the onset of this glottalization relative to the oral constriction can vary from lead to simultaneous to lag, making glottalization different from nasalization or aspiration. Esling et al. (Reference Esling, Fraser and Harris2005) divide the first dimension into ‘laryngealized’ (creaky voice) vs. ‘glottalized’ (full glottal stop, no creaky voice), and the second dimension into ‘pre’ vs. simultaneous. Thus they distinguish preglottalized, e.g.[ʔm], from preglottalized+ laryngealized, e.g. [ʔm̰], or prelaryngealized+laryngealized, e.g.[ ̰m̰], etc. An example of the latter would be Trique, where ‘[g]lottalization always precedes and overlaps the initial portion of the consonant’ (DiCanio Reference DiCanio2010: 232). Here we are concerned with any glottal constriction (whether full glottal stop or not) timed to fully or partially precede the oral constriction, i.e. both preglottalization and prelaryngealization in Esling et al.’s usage. (We will not discuss postglottalization here.)

Because glottalization can occur before, during, and after a primary articulation, its timing cannot always be specified as exclusively pre, simultaneous or post, and thus the situation with preglottalization is more complex than with prenasalization or preaspiration. Nonetheless, clear phonetic sequences have been documented. Esling and colleagues have used laryngoscopic imaging to demonstrate that in some languages a full glottal stop precedes an oral constriction. For example, Esling et al. (Reference Esling, Fraser and Harris2005) show full (‘moderate’) glottal stops in the preglottalized resonants of Nuuchahnulth (a Wakashan language, also called Nootka), while Edmondson et al. (Reference Edmondson, Esling, Harris and Wei2004: 61) show that the preglottalized consonants of Sui (Tai-Kadai) are ‘phonetically a moderate glottal stop followed by a voiced stop, a voiced nasal, a voiced approximant or a voiced fricative’, without implosion or adjacent vowel laryngealization. Esling et al. (Reference Esling, Fraser and Harris2005: 397ff.) also provide duration measurements, and show that Nuuchahnulth preglottalized resonants are almost twice as long as nonglottalized consonants and glottal stop. These cases thus seem to involve two phonetic segments, though they are treated as single segments phonologically (e.g. in the Carlson et al. (Reference Carlson, Esling and Fraser2001) Illustration of the IPA).

In contrast, if its glottal constriction overlaps extensively either with its oral constriction or with a preceding segment, a preglottalized consonant’s duration may be like that of a simple single segment. For example, English voiceless stops often exhibit allophonic preglottalization, especially when in coda position. This is often called ‘glottal reinforcement’, e.g. Roach (Reference Roach1973) and references cited by Esling et al. (Reference Esling, Fraser and Harris2005), MacMahon (Reference MacMahon, Aarts and McMahon2006) and Garellek (Reference Garellek2010). Glottal reinforcement can be realized as laryngealization of the preceding vowel, without any lengthening of the stop interval, e.g. Huffman (Reference Huffman2005). In Lai, glottalized (usually preglottalized) sonorants are much shorter than their plain counterparts (Roengpitya Reference Roengpitya1997, Plauché et al. Reference Plauché, de Aconza, Roengpitya, Weigel, Bergen, Plauché and Bailey1998). Thus some preglottalized segments have durations consistent with single phonetic segments. It may be that when preglottalization involves a full glottal stop, then the duration is that of a sequence, but when it involves modified voicing, segment duration may be unaffected or even reduced.

Examples of languages where preglottalization varies between full glottal stop and laryngealization include Hupa (Athabaskan), where the glottalization associated with sonorants is often realized as creakiness rather than a full glottal stop, especially in the case of preglottalized sonorants (Gordon Reference Gordon1996: 167), and Yurok (Blevins Reference Blevins2003).

2.3.2 Phonology

Preglottalized consonants contrast with plain consonants in at least some languages. Anonby (Reference Anonby2006), Baird (Reference Baird2002: 94) and DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010) in their Illustrations of the IPA, give minimal and near-minimal pairs. Anonby’s (near) minimal pair contrasts word-initial plain and preglottalized [w] and [j]. Baird gives Kéo minimal pairs contrasting plain vs. preglottalized (and prenasalized) versions of the same (obstruent) stops, for example /bala/ vs. /ʔbala/ vs. /mbala/. Baird (Reference Baird2002: 93) also notes that Kéo, ‘a highly isolating language, with primarily monosyllabic and disyllabic words with basic (C)V((C)V) syllable structure’, has no morphophonemic alternations, and ‘very little allophony’; that is, the preglottalized consonants seem to be consistently preglottalized, not variable. DiCanio includes contrasts of /n/ vs. /ʔn/, /nd/ vs. /β/, vs. /ʔβ/, and /j/ vs./ʔj/, among others. Nonetheless, in many languages preglottalized consonants are allophones of glottalized consonants that can also be postglottalized. Plauché et al. (Reference Plauché, de Aconza, Roengpitya, Weigel, Bergen, Plauché and Bailey1998) and Howe & Pulleyblank (Reference Howe and Pulleyblank2001) suggest that in languages with glottalized sonorants, these are always preglottalized in onsets but mostly postglottalized (sometimes preglottalized) in codas. Hupa (Gordon Reference Gordon1996) is another such a case, at least underlyingly.

Arguments that preglottalized consonants (whether phonemes or allophones) are phonologically single segments are often parallel to those made for prenasalized consonants. For example, Gordon (Reference Gordon1996) argues for a single-segment analysis of the glottalized sonorants of Hupa on distributional grounds. First, if treated as clusters, glottal-stop+sonorant+obstruent sequences would be the only three-segment tautosyllabic clusters. Second, preglottalized sonorants frequently occur stem-finally, and stem-final tautomorphemic clusters are very rare in Athabaskan. Similarly, Keller (Reference Keller2001) notes that in Brao-Krung, the preglottalized voiced stops form clusters with liquids just like single segments do, e.g. [bl] contrasts with [ʔbl], but there are no other three-segment clusters. DiCanio (Reference DiCanio2010) notes that, while preglottalized consonants have been analyzed as clusters in related dialects, in Itunyoso Trique, the distribution of preglottalized consonants is different from that of other clusters. For example, clusters are generally word-initial, but the preglottalized consonants occur only in onsets of word-final syllables, so generally word-medially. Stieng (Haupers Reference Haupers1969) and Halang (Cooper & Cooper Reference Cooper and Cooper1966) are other languages in which such distributional arguments can be made.Footnote 8

Another kind of argument is correspondence with segments that are clearly unitary. For example, in Kéo (Baird Reference Baird2002), the preglottalized voiced stops ‘correspond to implosives in cognate words’ in related languages. Similarly, Wedekind (Reference Wedekind1990) notes in passing that while in Ethiopian languages the preglottalized sonorants tend to be analyzed as sequences, sometimes the preglottalized flap can be clearly related to implosive [ɗ]. In languages where preglottalized sonorants form a series with ejective stops, which are clearly single segments, the sonorants will likewise be considered unitary (e.g. Nuuchahnulth). And preglottalized allophones of clearly unitary segments, such as voiceless stops (e.g. English, Thai, Mah-Meri), will be considered unitary too.

Blevins (Reference Blevins2003) gives several arguments for the unitary status of preglottalized sonorants in Yurok from phonological rules of the language that treat them, together with ejectives, as single segments (all, Blevins argues, with a glottal constriction feature). For example, if they were analyzed as clusters, then their behavior in neutralizations with plain sonorants would be unexpected: loss of glottalization would be the only case in the language of cluster simplification, and addition of glottalization would be the only case in the language of segment insertion.

In sum, preglottalized consonants in at least some languages behave phonetically and/or phonologically like single segments rather than like sequences, with (the onset of) glottalization preceding the primary oral constriction.

We have seen that the phenomena of prenasalization, preaspiration, and preglottalization have received significant treatments in the phonetic and phonological literature. We now turn to our proposals about how these can be represented within the IPA.

3 Proposal

3.1 Diacritics

The second principle of the IPA states that ‘[t]he IPA is intended to be a set of symbols for representing all the possible sounds of the world’s languages’, and the fifth principle clarifies this by noting that ‘the use of symbols in representing the sounds of a particular language is usually guided by the principles of phonological contrast’ (IPA 1999: 159–160). Taken together, these principles make it clear that if a sound is both phonetically attested and plausibly used as a phoneme in at least some languages, a standard symbol should be available to represent it. Prenasalization, preglottalization and preaspiration are all attested in multiple languages as properties of single unit phonemes, and in additional languages as allophones. We believe that enough evidence has accumulated to justify providing a single-segment notation for these phenomena. While experienced phoneticians are comfortable extending and innovating usage of existing diacritics and symbols, less experienced users appreciate greater coverage and exemplification on the chart. Below we provide suggestions for new diacritics and how they might fit into the IPA chart.

We propose three (sets of) superscript diacritics preceding a base symbol. We have seen that these are already commonly, though by no means universally, used by researchers, including in JIPA. Such diacritics are clearly interpretable and easily deployed by users.

For two of these cases, prenasalization and preaspiration, we can extend the usage of the existing diacritics for nasal release and aspiration, respectively, by explicitly endorsing their use in a new location. The existing Aspirated diacritic is shown on the current chart as [tʰ dʰ], in Unicode the ‘modifier letter small h’, U+02B0. The proposal for preaspiration is to use this same diacritic (the same Unicode character) before a base symbol. As there is no evidence that preaspiration occurs with voiced stops, the proposal is to show it only before a voiceless stop, e.g. [ht]. As noted in the ‘Introduction’ section above, this preaspiration diacritic is already part of the Extended IPA, and as such is listed in the ‘Symbols for disordered speech’ section of Appendix 3 of the Handbook (IPA 199: 193). For clarity, it might also be desirable to add the qualifier ‘(Post)’ to the name of the diacritic now titled ‘Aspirated’ (thus distinguishing Preaspirated vs. (Post)aspirated).Footnote 9

The existing Nasal release diacritic, introduced after the 1989 Kiel Convention, is shown on the current chart as [dn], in Unicode the ‘superscript Latin small letter n’, U+207F. Prenasalization would be shown as [nd]. There is then some ambiguity as to exactly how many/which superscript nasal diacritics are allowed – should the diacritic agree in place of articulation with the base symbol? This ambiguity already holds for the existing Nasal release diacritic: Neither on the chart nor in the Handbook is it specified whether [m], [η], etc. may be used to indicate homorganicity, though this is certainly common practice. We suggest that such homorganic usage be explicitly recognized and officially endorsed, for both nasal release and prenasalization, though not necessarily on the chart itself.Footnote 10 In Unicode, ‘modifier letter small m’, ‘modifier letter small eng’ and other nasal diacritics are already available in the Phonetic Extensions and Phonetic Extensions Supplement character sets.

In the case of preglottalization, there is no existing IPA glottal diacritic that can be re-purposed. However, like a few other non-IPA diacritics, it is already available in Unicode: ‘modifier letter glottal stop’, U+02C0. It could appear on the chart as [ʔt] and [ʔn], making clear that both obstruents and sonorants can be preglottalized. It would also be possible to extend our proposal to encompass postglottalization, that is, the same diacritic following a base symbol, though we will not pursue that possibility here.

3.2 Chart

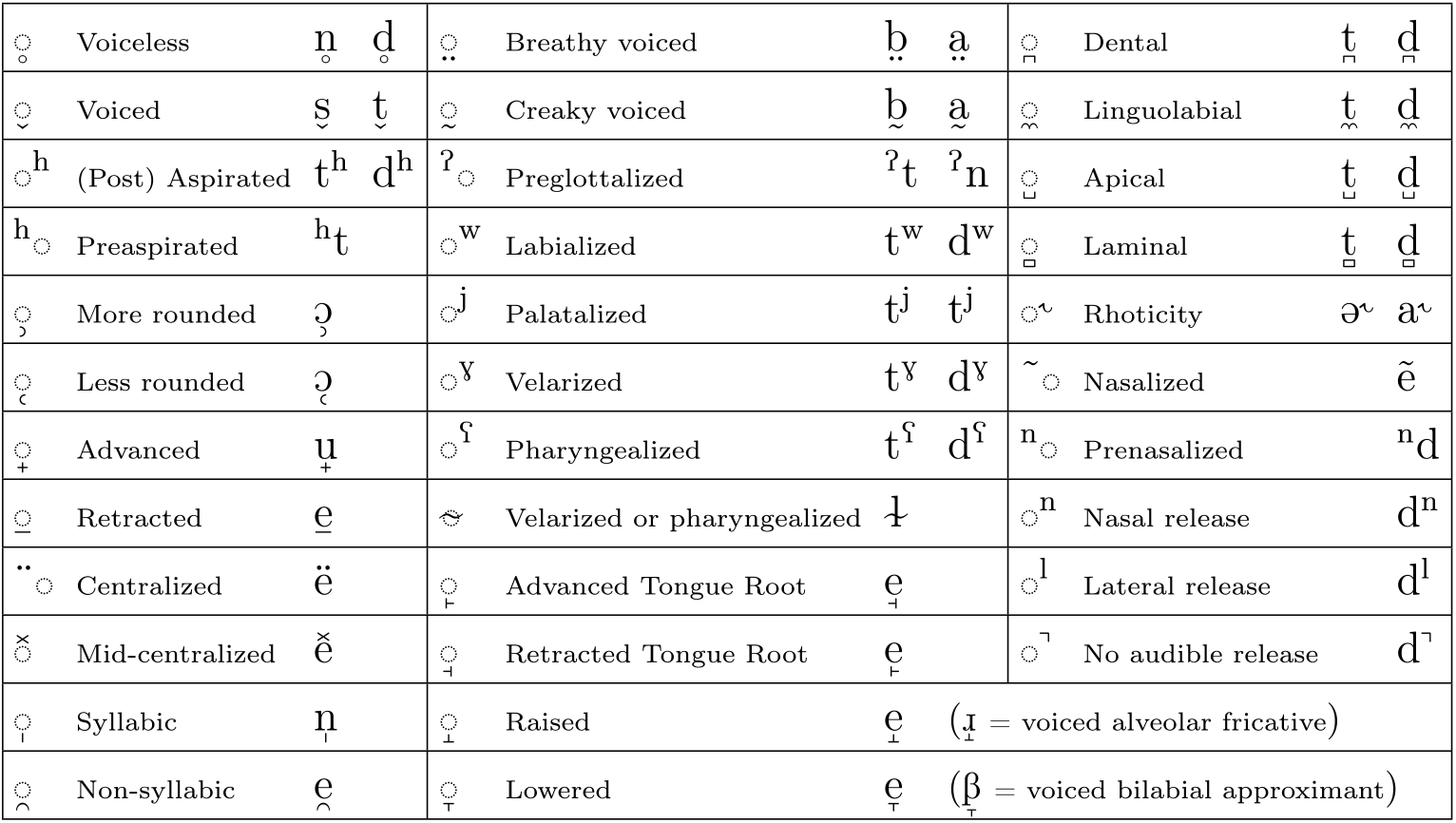

As for how to fit these additions into the existing IPA Diacritics chart, we suggest that moving a few existing diacritics within the chart can free up the needed space. These suggestions are shown in the proposed chart in Figure 1. With these changes we not only create new space, but we bring some related diacritics together. To make room for ‘Preaspirated’ under Aspirated, we move the ‘Rhoticity’ diacritic with the other tongue blade diacritics. To make room for ‘Preglottalized’ under ‘Creaky voiced’, we move ‘Linguolabial’ also with the other tongue blade diacritics, under ‘Dental’. Even with these additions to the third column of diacritics, ‘Prenasalized’ fits between ‘Nasalized’ and ‘Nasal release’.

Figure1: Proposed changes to IPA Diacritics chart.

For maximum clarity, we have added throughout the Diacritics chart placeholders (small dashed circles) for the base symbols for all diacritics. Such placeholders are now commonly seen in online versions of the IPA chart, e.g. http://westonruter.github.io/ipa-chart/keyboard/, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Phonetic_Alphabet#Diacritics_and_prosodic_notation, http://www.internationalphoneticalphabet.org/ipa-charts/diacritics/, and the Association’s own clickable chart, currently at https://linguistics.ucla.edu/people/keating/IPA/inter_chart_2018/IPA_2018.html. We do not mean to suggest that the placeholder needs to be a dashed circle (a reviewer prefers a square), but we do suggest that using some overt placeholder is helpful for making clear the intended locations not only of our new diacritics, but of diacritics in general.

3.3 Discussion

Principle 4c includes the recommendation that diacritics be used ‘when the introduction of a single diacritic obviates the necessity for designing a number of new symbols’ (IPA 1999: 160). Since many different sounds can be prenasalized, preglottalized or preaspirated, the economy of diacritics is clearly preferable. It is true that use of a tie bar to represent these sounds (n͡d ʔ͡t h͡t) is also economical, and is an appropriate notation which we do not oppose. However, using the tie bar this way is itself also an informal extension of the IPA, as the chart refers only to its use for ‘affricates and double articulations’. On balance, we believe that superscript diacritics are a better choice in the modern word-processing context, since tie bars often require special line-spacing adjustments in order to be legible.

We recognize that for prenasalization, the most common transcription in the literature seems to be a simple sequence (without tie bar). However, we believe that this is because of variation across languages in whether prenasalization forms a single segment or a cluster. As Cohn & Riehl (Reference Cohn, Riehl, Butler and Renwick2012) showed, these variants can be distinguished acoustically. For clusters, NC sequence notation remains available, but for clear single segments, the diacritic offers an unambiguous transcription. More generally, differences in usage of the IPA will continue to arise from phonetic differences across languages, or from different interpretations of a given case, but our proposal extends the IPA options that are available for phonetic and phonological characterizations.

Another alternative for preglottalization seen in published research (e.g. Gordon Reference Gordon1996, Esling et al. Reference Esling, Fraser and Harris2005 for ‘prelaryngealization’) is an extension of the Creaky voiced combining diacritic into a free-standing diacritic that can precede the base symbol. When another segment precedes the preglottalized segment, then the diacritic docks under it. Thus a preglottalized /t/ by itself could be notated as [ ̰t], and that segment after an [a] would be [a̰t]. This notation represents the perceptual importance of the quality of voicing adjacent to a glottalized consonant. However, it is visually awkward, and loses the potential distinction between creaky voice on a vowel, and preglottalization of a consonant.

Finally, Blevins (Reference Blevins2003) uses a preceding apostrophe for preglottalization (e.g. [’l], extending the use of this diacritic from ejectives. This notation represents in a clear way the equivalence between ejective obstruents and glottalized sonorants, extending the common orthographic use of apostrophe to represent glottal stop. (See also Carlson et al. Reference Carlson, Esling and Fraser2001.) However, as a phonetic diacritic, it removes, or makes unclear, the meaning of apostrophe as involving not just glottal constriction but also a glottalic egressive airstream mechanism. It might also be visually confusable with the diacritic for primary stress.

Our proposal for preceding superscripts extends the IPA diacritic system to a new location. The Handbook (1999: 15) says only that ‘[d] iacritics are small letter-shaped symbols or other marks which can be added to a vowel or consonant symbol to modify or refine its meaning in various ways. A symbol and any diacritic or diacritics attached to it are regarded as a single (complex) symbol’, without discussion of precisely where diacritics can be added. Adding the upper-left position for diacritics is not extreme, since the other three positions (above, below, upper-right) seem to form an incomplete set. However, some potential concerns are worth addressing.

First, our proposal allows a ternary structure to segments that is not currently expressible. Aspiration, glottalization or nasalization could begin a segment, and something else could end it. Our conclusion from the literature is that such notations are already in use; for example, in their Illustration of the IPA, Riehl & Jauncey (Reference Riehl and Jauncey2005) give /mbw/ as a single segment.

Second, might there ever be a parsing ambiguity as to whether a given diacritic is following vs. preceding its base symbol? Currently in the IPA, all superscript diacritics follow their base symbol, so there is no ambiguity. But under our proposal, could a sequence like e.g. [php] arise, in which the affiliation of the [h] is not clear because the language has both postaspiration and preaspiration? We have seen no such cases for preaspiration or prenasalization, but, for those researchers who use [ʔ] for both preglottalization and postglottalization, ambiguous sequences are indeed possible, due to the common pattern of preglottalization in onsets but postglottalization in codas (e.g. Plauché et al. Reference Plauché, de Aconza, Roengpitya, Weigel, Bergen, Plauché and Bailey1998). Word-medially, a [ʔ] could represent either of these allophones. For example, Plauché et al. (p. 385) list the Yowlumne word [ts’olʔlol] as an example of coda glottalization ([lʔ]), but the sequence appears consistent with onset glottalization ([ʔl]) as well (though all of their examples show onset consonants following vowels, not consonants). However, for any such ambiguous cases, the IPA Syllable boundary diacritic can be used to make the parse clear, e.g. [ts’olʔ.lol]. It is also true that if the inventory of the language is not known to a reader, the interpretation of a given diacritic could be unclear. For example, Esling et al. (Reference Esling, Fraser and Harris2005: 406) give a Nuuchahthulth word with the sequence [mʔj]. With the knowledge that this language has preglottalization but not postglottalization, the sequence is clear. Again, the syllable boundary diacritic could be used here for maximum clarity.

Finally, if these new diacritics represent specifically initial events within a segment, are the interpretations of existing diacritics implicitly changed? Must we now understand diacritics that follow their base symbol to refer exclusively to events at the end of a segment? In our view, no: only diacritics with ‘pre’, ‘post’ or ‘release’ in their names would have a limited temporal interpretation. The other diacritics would remain ambiguous as they are now. Indeed, no IPA transcription is intended to make detailed claims about timing, and all diacritics will continue to be used for a variety of articulations that are not necessarily clearly limited to a specific short time interval. The addition of new diacritics to the chart simply increases the resources available to the transcriber. It would of course be possible to re-define other existing diacritics to have more specific temporal interpretations, making it desirable to distinguish ‘pre’ vs. ‘post’ uses for these as well. Such extensions are doubtless already seen in the literature. However, such possibilities are well beyond our goal in this proposal, which is to address these most common, seemingly almost standard, instances of preceding diacritics.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, we propose that the Association consider the introduction of three new superscript diacritics preceding their base symbol to indicate preaspiration, preglottalization, and prenasalization. The diacritic for preaspiration is already available in the ExtIPA and is derived from the existing diacritic for postaspiration; the diacritic for prenasalization is derived from the existing diacritic for nasal release; the diacritic for preglottalization is new, derived from the glottal stop symbol. All three diacritics are already available in Unicode-compliant character sets. We have suggested how the current chart of IPA diacritics could be revised to accommodate these additions.

Acknowledgements

We thank John Esling, two anonymous reviewers, and members of the UCLA Phonetics Lab for helpful comments, especially Yu Tanaka for pointing out the Japanese case and providing examples.