In 2014, Danièle Nouy – the first Chair of the Supervisory Board of the ECB – praised the ‘robust accountability’ framework of the newly established SSM. In her introductory remarks at an EP committee hearing, Nouy argued that ‘this framework is perhaps one of the most far-reaching that is in place for an independent central bank that is responsible for supervision. I believe we have already lived up to the word and spirit of this framework’ (Reference NouyNouy 2014). The Chair of the Supervisory Board is not alone in emphasising the strength of the accountability obligations set in place by the SSM Regulation (Council Regulation 1024/2013). Ter Kuile and colleagues claim that the SSM has successfully established a form of ‘tailor-made accountability which keeps power in check while respecting the independence of the banking supervisors’ (Reference Ter Kuile, Wissink and Bovenschen2015: 155). In terms of political accountability, the SSM created multiple reporting requirements for the ECB – regulated for the first time through an Interinstitutional Agreement with the EP and a Memorandum of Understanding with the Council (European Central Bank 2021a). In this context, Fromage and Ibrido argue that the accountability framework of the SSM ‘could open new avenues in the ECB’s … quest for reinforced democratic accountability’ that could be extended to the relationship with the EPG on monetary policy (2018: 306). Overall, the mechanisms to hold the ECB accountable in banking supervision are generally seen as a marked improvement over similar arrangements in monetary policy (Reference BraunBraun 2017: 47).

The reason why ECB accountability was contentious in the first place concerns its status as a non-majoritarian, technocratic organisation and at the same time one of the most independent central banks in the world (Reference CurtinCurtin 2017; Reference ElgieElgie 2002; Reference Naurin, Gustavsson, Karlsson and PerssonNaurin 2009). Generally speaking, independent central banks with unequivocal mandates to maintain price stability are not exceptional institutions: in fact, they have been part of the monetary policy orthodoxy in advanced economies since the late 1980s (Reference Alesina and SummersAlesina and Summers 1993; Reference Cukierman, Webb and NeyaptiCukierman et al. 1992). Furthermore, it is not uncommon for central banks to take over responsibilities for banking supervision, albeit the latter is more controversial due to potential situations when monetary and supervisory tasks can come into conflict (Reference BuiterBuiter 2014: 270). From the perspective of democratic accountability, the political independence of central banks was always bound to be problematic (Reference ElgieElgie 1998; Reference LevyLevy 1995). When central banks take decisions independently from democratic elections, there is no political debate about the trade-offs involved in monetary policy or financial supervision. Instead, such decisions become cloaked in the technical language of expertise (Reference StiglitzStiglitz 1998: 216–217). To address the shortcoming, the legal framework of central banks typically includes political accountability mechanisms – most often in the form of parliamentary oversight or an institutionalised dialogue with governments (Reference De Haan, Amtenbrink and EijffingerDe Haan et al. 1999: 178–179). The scope and functioning of these mechanisms differ, however, from setting to setting.

This chapter investigates how the EP exercises oversight of the ECB in the field of banking supervision. The goal is to evaluate the extent to which the ECB is being held accountable by its main political interlocutor in the SSM framework – the EP’s ECON Committee. Following the theoretical approach outlined in Chapter 3.3, the focus is on parliamentary Q&A exchanged between the two institutions both orally and in writing. The analysis below is based on 283 letters with questions and 13 public hearings that took place at the ECON Committee between October 2013 (since the adoption of the SSM Regulation) and April 2018. The findings reveal that MEPs ask many questions of the ECB on banking supervision, but oversight remains ‘weak’ – focused on requests for information and justification of conduct. The emphasis on weaker oversight questions stems from the ECB legal framework, which imposes strict confidentiality requirements regarding decisions about supervised banks, as well as from the strong independence of the ECB in the EU political system. For its part, the ECB is open to justifying its conduct and explaining its decisions to MEPs, but it rarely agrees to policy changes in response to EP oversight. In line with the expectations set out in Chapter 3.3.1, the preponderance of weak oversight questions and explicit, justificatory replies places this oversight relationship in scenario 4 - ‘Transparency’.

The chapter is structured as follows. The first part introduces the background of the SSM and its main institutional features. The second part explains the key issues in the accountability relationship between the EP and the ECB in banking supervision, drawing on principal–agent insights. The third part provides the empirical analysis of oversight interactions, focusing on three aspects: (1) the profile of MEPs asking questions of the ECB on banking supervision, (2) the types of questions asked and substantive policy issues raised, and (3) the responsiveness of the ECB as reflected in answers to parliamentary questions. The conclusion problematises the accountability shortfalls of the SSM in relation to the six scenarios of oversight outlined in the theoretical framework (Chapter 3.3.1).

4.1 Background: The Crisis and the SSM Regulation

Before the creation of the SSM, the subject of ECB accountability revolved around its monetary policy functions as the central bank of the Eurozone. From the very beginning, the academic debate on the topic was dominated by the tension between the ECB’s high degree of independence and the scope for holding it accountable for its decisions (Reference CurtinCurtin 2017; Reference Dawson, Maricut-Akbik and BobićDawson et al. 2019; Reference MagnetteMagnette 2000). The political independence of the ECB is constitutionally enshrined in the Treaties and has been consistently implemented since the establishment of the Bank in 1998 (Reference SchellerScheller 2004: 121). Specifically, Article 130 TFEU prohibits the ECB from seeking or taking ‘instructions from Union institutions, bodies, offices or agencies, from any government of a Member State or from any other body’. Moreover, Article 282(3) TFEU specifies that the ECB ‘shall be independent in the exercise of its powers and in the management of its finances’ and that ‘Union institutions, bodies, offices and agencies and the governments of the Member States shall respect that independence’. In contrast to national central banks, whose mandate can be changed through parliamentary majorities, the ECB legal framework can only be altered through Treaty changes and hence the unanimous vote of all EU Member States (Reference De HaanDe Haan 1997: 413–414). In the official institutional discourse, the ECB does not see its independence as a hindrance to democratic accountability; conversely, the two are often presented as ‘two sides of the same coin’ – equally necessary to ensure the bank’s legitimacy (Reference CœuréCœuré 2017; European Central Bank 2002: 46).

Under the circumstances, the Monetary Dialogue with the EP became the main instrument of political accountability of the ECB. The Monetary Dialogue has three dimensions: (1) the presentation of an annual report of activity before the EP, which triggers a parliamentary resolution in response; (2) the participation of the ECB President in quarterly hearings of the ECON Committee; and (3) the submission of written questions to the ECB by individual MEPs (Reference Fromage and IbridoFromage and Ibrido 2018: 299–300). Unsurprisingly, public hearings with the ECB President received the most attention. Previous studies criticised the generic and sometimes superficial scope of the Monetary Dialogue with the EP, which was focused – especially in the early years – on debating economic and financial policies rather than contesting the performance of the ECB (Reference Amtenbrink and van DuinAmtenbrink and van Duin 2009; Reference BraunBraun 2017: 42; Reference GrosGros 2004). Moreover, empirical research found that the ECB President often repeats to MEPs the information conveyed in his regular press conferences, which receive more media attention than the Monetary Dialogue (Reference BelkeBelke 2017; Reference Claeys, Hallerberg and TschekassinClaeys et al. 2014). Nonetheless, it is widely recognised that the Monetary Dialogue has improved over the years: MEPs ask questions that are both more frequent and more relevant, while the ECB is generally responsive to their requests (Reference Collignon and DiessnerCollignon and Diessner 2016; Reference Eijffinger and MujagicEijffinger and Mujagic 2004; Reference Fraccaroli, Giovannini and JametFraccaroli et al. 2018). Overall, the pre-SSM record of the EP as an accountability forum of the ECB is mixed; as the name suggests, the Monetary Dialogue was more a ‘dialogue’ than an intense ‘holding to account’ relationship.

It was against this background that the ECB received additional powers to supervise the banking system in the Eurozone. In fact, the SSM was one of the key institutional reforms adopted at the EU level in response to the euro crisis (see Chapter 2.1.2). Its rationale was rooted in the way in which the 2008–2009 global financial crisis unfolded in Europe as a sovereign debt crisis: failing banks were ‘rescued’ by governments using public funds, and then some states were ‘rescued’ using an EU scheme, thus creating a vicious circle between banks and sovereigns (Reference Schoenmaker and VéronSchoenmaker and Véron 2016: 6). At the same time, a European system of banking supervision was portrayed as the necessary counterpart to the potential direct recapitalisation of banks through the ESM (Eurozone Summit 2012), although the latter never materialised. Proposed in 2012 by European Council President Herman Van Rompuy, the SSM aimed to integrate supervisory tasks at the EU level in order to ‘ensure that the supervision of banks in all EU Member States is equally effective in reducing the probability of bank failure and preventing the need for intervention by joint deposit guarantees or resolution funds’ (Reference Van RompuyVan Rompuy 2012: 4).

After the political goal was set, it was quickly decided that the ECB should take over the new task, since the possibility was already foreseen in Article 127(6) TFEU. However, there were some concerns over the distributive implications of supervisory decisions and the difficulties of separating a central bank’s monetary and supervisory functions (Reference BuiterBuiter 2014). Moreover, supervisory decisions could have conflicting objectives in themselves, such as ‘financial stability, investor and depositor protection, consumer protection and financial crime’ (Reference AlexanderAlexander 2016: 486). The SSM Regulation clearly prioritised one of these objectives, namely ‘the safety and soundness of credit institutions and the stability of the financial system within the Union and each Member State’ (SSM Regulation, Article 1). Consistent supervision and financial integration are also cited among the main goals of the SSM (European Central Bank 2019). So far, the ECB has not issued a quantifiable operationalisation of these objectives, although several official documents emphasise the need to act as a ‘tough and fair’ bank supervisor (Reference NouyNouy 2015).

Once established, the SSM became a complex institutional system involving the ECB and national supervisors of Eurozone Member States – renamed as NCAs. As of December 2020, the ECB is responsible for the direct supervision of 115 so-called significant banks, which together hold almost 82 per cent of the banking assets in the Eurozone (European Central Bank 2020a). Daily supervision is organised into Joint Supervisory Teams (JSTs), led by the ECB and comprising members of NCAs. The tasks of the ECB in the context are clearly delineated: conducting supervisory reviews, on-site inspections, and investigations; granting and withdrawing banking licences; assessing banks’ acquisition and disposal of qualifying holdings; ensuring compliance with EU prudential rules; and setting higher capital requirements (‘buffers’) in order to counter financial risks (European Central Bank 2019). The remaining banks are known as ‘less significant’ and continue to be supervised by NCAs, with the ECB taking a back seat. The main decision-making body is the Supervisory Board, composed of six ECB representatives (including the chair and the vice-chair) and one representative from the NCA of each participating Member State (SSM Regulation, Article 26).

To balance the expansion of ECB powers in banking supervision, separate accountability obligations were put in place at the political, legal, and administrative levels, hence adding to the already existing accountability toolbox on the monetary policy side of the ECB. In terms of political accountability, the relationship with the EP became central – in a similar way to the already established Monetary Dialogue. Unlike in monetary policy, the ECB was given additional political accountability obligations in banking supervision towards the Eurogroup and national parliaments (SSM Regulation, Articles 20–21). However, interactions with the Eurogroup remain confidential, while visits to national parliaments take place on an ad hoc basis, so it is very difficult to assess their functioning in a systematic manner. By contrast, EP hearings with the Chair of the Supervisory Board and the exchange of documents between the two institutions are public and occur regularly.

The accountability obligations of the ECB towards the EP in banking supervision are detailed in a first-time Interinstitutional Agreement signed between the two institutions (European Central Bank 2013). In line with the SSM Regulation, the obligations entail (1) the publication of an annual report on the execution of tasks conferred by the SSM Regulation; (2) participation of the Chair of the Supervisory Board in ordinary and ad hoc public hearings at the ECON Committee and, upon request, in confidential meetings with members of the Committee; (3) the provision of written response within five weeks to written questions sent by MEPs; and (4) the transmission of confidential, annotated records of the Proceedings of the Supervisory Board that allow ECON Members to understand the substance of discussions and decisions taken (Articles 1–4).

The implementation of these obligations needs to be understood in the broader context of parliamentary oversight of executive decisions. To contextualise the case, the next section links parliamentary oversight of ECB supervisory decisions with the principal–agent model. In addition, there is a discussion of the key issues in banking supervision relevant for the EP–ECB accountability relationship.

4.2 Political Accountability in Banking Supervision: Key Issues

The relationship between the ECB and the EP in banking supervision is an example of central bank accountability and, more generally, of legislative oversight of an executive agency delegated to fulfil specific functions. In some sense, this is a classic principal–agent relationship in which an authorised principal delegated powers to an agent with the expertise and policy credibility to carry out specific tasks (Reference MajoneMajone 1999: 3–4; Reference StrømStrøm 2000). Indeed, the EP contributed to the legal framework that gave the ECB an explicit mandate for banking supervision in the Eurozone. However, the SSM was created by a Council Regulation adopted through a special legislative procedure in which the EP was only consulted – and was thus on the same level as the ECB itself (Reference Amtenbrink and MarkakisAmtenbrink and Markakis 2019). While the ECON Committee was closely involved in the legislative process and even gained additional accountability powers in the SSM – as demonstrated by the Interinstitutional Agreement – it cannot accurately be considered the ‘principal’ of the ECB in the field. If anything, the Member States of the Eurozone, acting through the Council, are the main ‘principal’ of the ECB in banking supervision.

As a result, there are formal limitations to the EP’s powers to hold the ECB accountable for its supervisory decisions. If the EP depends on the Council for revising the ECB’s mandate in the SSM, then its ability to influence the incentive structure in which the agent operates (through ‘contracting’) is automatically curtailed. In addition, the SSM Regulation (Article 19) prohibits the ECB from taking instructions from other Union institutions. The SSM Regulation specifies that ‘the ECB should exercise the supervisory tasks conferred on it in full independence, in particular free from undue political influence’ (Recital 75; see also Article 19). This means that any recommendations made by the EP in its ‘Resolutions on the Banking Union-Annual Reports’ might have an informal impact on supervisory conduct but do not constitute formal mechanisms to sanction the ECB because parliamentary resolutions are never legally binding. On the plus side, the EP can veto the appointment of the Chair and Vice-Chair of the Supervisory Board and approve the dismissal of the former in case of poor performance or serious misconduct (SSM Regulation, Article 26). In addition, the ECB has the obligation to ‘cooperate sincerely with any investigations by the European Parliament, subject to the TFEU’ (SSM Regulation, Article 20(9)). Otherwise, there is a clear focus on accountability though monitoring and justification: the ECB has regular reporting obligations towards the EP, while MEPs can ask questions and pass (non-binding) judgement in their reports and resolutions (Interinstitutional Agreement, Article 1–4).

Furthermore, the accountability challenges faced by the EP and the ECB in banking supervision reflect basic principal–agent expectations. Most significantly, there are problems of (1) asymmetric information, as the ECB is an expert body possessing much more knowledge than the EP in the field of banking supervision, and (2) hidden action, given that ECB supervisory decisions remain unseen by MEPs (Reference StrømStrøm 2000: 270). Banking supervision is a highly technical area that requires financial, legal, and accounting expertise; moreover, there are strict confidentiality requirements that prevent the disclosure of sensitive supervisory data and decisions (Reference AngeloniAngeloni 2015). However, the risk of ‘agency drift’ – the ECB diverging from its mandate – is not the same as in monetary policy. The first difference lies in the selection procedure, as the EP can veto the appointment of the Chair of the Supervisory Board, but the same cannot be done for Members of the ECB Executive Board (Reference Fromage and IbridoFromage and Ibrido 2018: 296). The second difference concerns the nature of the mandate in banking supervision, where the ECB has to apply secondary law (Reference Ter Kuile, Wissink and Bovenschenter Kuile et al. 2015: 167–168). By contrast, in monetary policy, the ECB is free to decide and implement its preferred policy instruments within the confines of the Treaty (especially Articles 119 and 123 TFEU). This means that banking supervision leaves limited room for discretion in comparison to monetary policy. The SSM legal framework is elaborate, based on international regulatory standards (Basel III), which were translated into EU legislation through the Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRD IV) and the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR). The ECB is responsible for enforcing these rules, which again are subject to change by the co-legislators, that is, the EP and the Council. The dynamic allows the EP to act as a classic oversight body, checking whether ECB actions deviate from legislative intent.

In terms of substance, the most contentious accountability issue in banking supervision refers to the transparency of supervisory decisions and bank-level information. Here, there is a huge gap between American and European practices regarding the disclosure of financial supervisory data, as the latter is traditionally more inclined towards confidentiality (Reference Gandrud and HallerbergGandrud and Hallerberg 2018: 1029). The reasons for secrecy concern legality, trust between the supervisor and the supervisee, and financial stability at large. Legally, EU bank supervisors are not allowed to disclose information that would endanger the competitive position of a credit institution on the market (Directive 2003/6/EC on insider dealing and market manipulation). In relation to trust, banks are more likely to share sensitive information with the supervisor if they are confident that this will be treated confidentially. From the perspective of financial stability, liquidity problems at a bank can trigger bank runs and panic in the population (Reference AngeloniAngeloni 2015). Conversely, the arguments for transparency are more general: transparency is a pre-condition for accountability that increases the legitimacy of the supervisors by allowing accountability forums to judge whether the supervisor is acting in the public interest. Moreover, transparency reduces the scope for arbitrary decisions and creates stable expectations that incentivise banks to adhere to regulations (Reference Liedorp, Mosch, van der Cruijsen and de HaanLiedorp et al. 2013: 311).

In the Interinstitutional Agreement with the ECB, the EP consented to balance accountability obligations with secrecy requirements (Article 5). Accordingly, MEPs can read a non-confidential version of Records of the Proceedings of the Supervisory Board, which are summaries of discussions after each meeting. In addition, there are confidential ‘in camera meetings’ that take place before hearings of the Chair of the Supervisory Board at the ECON Committee. These are meetings between the coordinators of all political groups, the ECON Chair and Vice-Chairs, and the Chair of the Supervisory Board, who work on organising the agenda of public hearings.Footnote 13 These encounters are reported to be much more confrontational than public hearings, with ‘tough’ language that is often absent in public interactions between the two institutions.Footnote 14 But the downside of confidential accountability is the suspicion that there is something to hide; after all, how can the public be sure that the ECB is being held accountable behind closed doors? The same problem is found in the accountability interactions between the ECB and the Council in banking supervision: formally, the provisions of the Interinstitutional Agreement are mirrored in a Memorandum of Understanding signed in 2013 between the ECB and the Council, more specifically the Eurogroup. However, exchanges of views and questions from national finance ministers remain confidential, in line with Eurogroup practices (Reference PuetterPuetter 2006). It is thus impossible to evaluate their accountability relationship other than to say that the Chair of the Supervisory Board participates in Eurogroup meetings at least twice per year, when they appear to discuss the same topics as in hearings at the ECON Committee (Council of the European Union n.d.).

Two final issues further complicate the scope for political accountability of the ECB in banking supervision. On the one hand, the SSM is part of a banking union that is still work-in-progress. Several legislative dossiers amending or seeking to complete the banking union are currently under review, which means that the framework of rules in which the ECB operates remains in flux (Council of the European Union 2018a). On the other hand, the banking union is a complex arrangement spread over several institutions: the EBA (in charge of banking regulation), the ECB (responsible for banking supervision), and the SRB/the Commission (in charge of banking resolution) (Council of the European Union 2018b). In addition, the ECB is part of a layered supervisory system in which it acts in coordination with domestic supervisors, the NCAs. This means that the ECB functions in a changing environment where the division of competences is difficult to disentangle. Holding the ECB accountable as a bank supervisor is bound to be complicated from the outset.

Having established the main parameters of political accountability in the SSM, the next section turns towards the analysis of oversight interactions between the EP and the ECB in banking supervision in the early years since the establishment of the SSM. Considering the accessibility of documents, the analysis is based on transcripts of public hearings and letters exchanged between the two institutions in the framework of their accountability relationship. The analysis follows the Q&A approach to legislative oversight (outlined in Chapter 3.3) and is divided into three parts, covering (1) the frequency of interactions and profile of questioners, (2) types of questions addressed by MEPs, and (3) types of answers provided by the ECB on banking supervision.

4.3 Oversight Interactions: Main Findings

The SSM Regulation was adopted in October 2013, giving the ECB one year to prepare for taking over banking supervision in the Eurozone. The dialogue with the ECON Committee started right away, while the first Chair of the Supervisory Board, Danièle Nouy, took office in January 2014. The analysis below covers the period from October 2013 to April 2018 and includes 283 written letters exchanged between the two institutions and 13 public hearings of the Chair of the Supervisory Board at the ECON Committee.Footnote 15

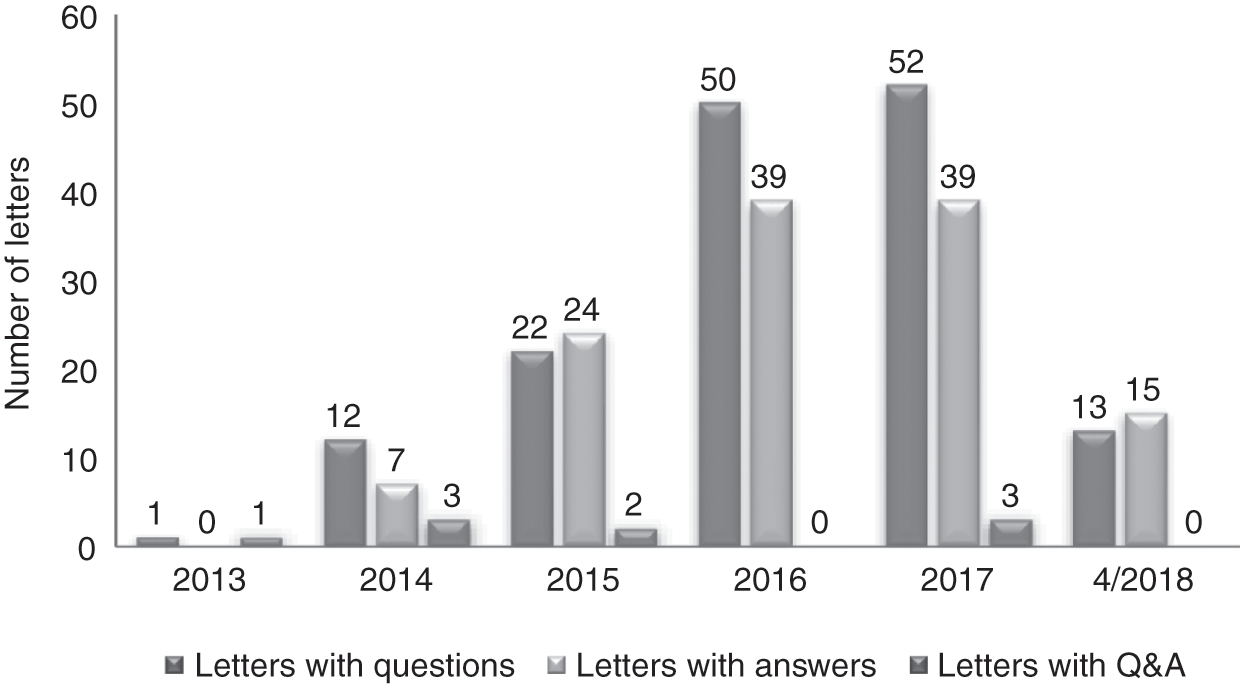

Figure 4.1 offers an overview of the letters identified in the period under focus. Overall, the ECB used 123 documents to answer 150 letters sent by MEPs in the SSM framework. There are two reasons why the number of letters with questions does not correspond to the number of letters with answers published by the ECB. First, letters sent at the end of the calendar year are answered early in the new year, so there is never an equivalence between the numbers of documents exchanged per year. Second, the ECB has the practice of using one document to answer multiple letters sent by the same MEP(s). This is not to say that individual questions go unanswered, but that one document can contain multiple answers. At the same time, seven ECB letters simply followed up on questions raised during hearings at the ECON Committee. In addition, three documents included both questions and answers addressed by Members of the ECON Committee to ECB President Mario Draghi before the appointment of the first Chair of the Supervisory Board.

Figure 4.1 Overview of letters exchanged between the EP and the ECB on banking supervision (October 2013–April 2018). Total letters identified: 283

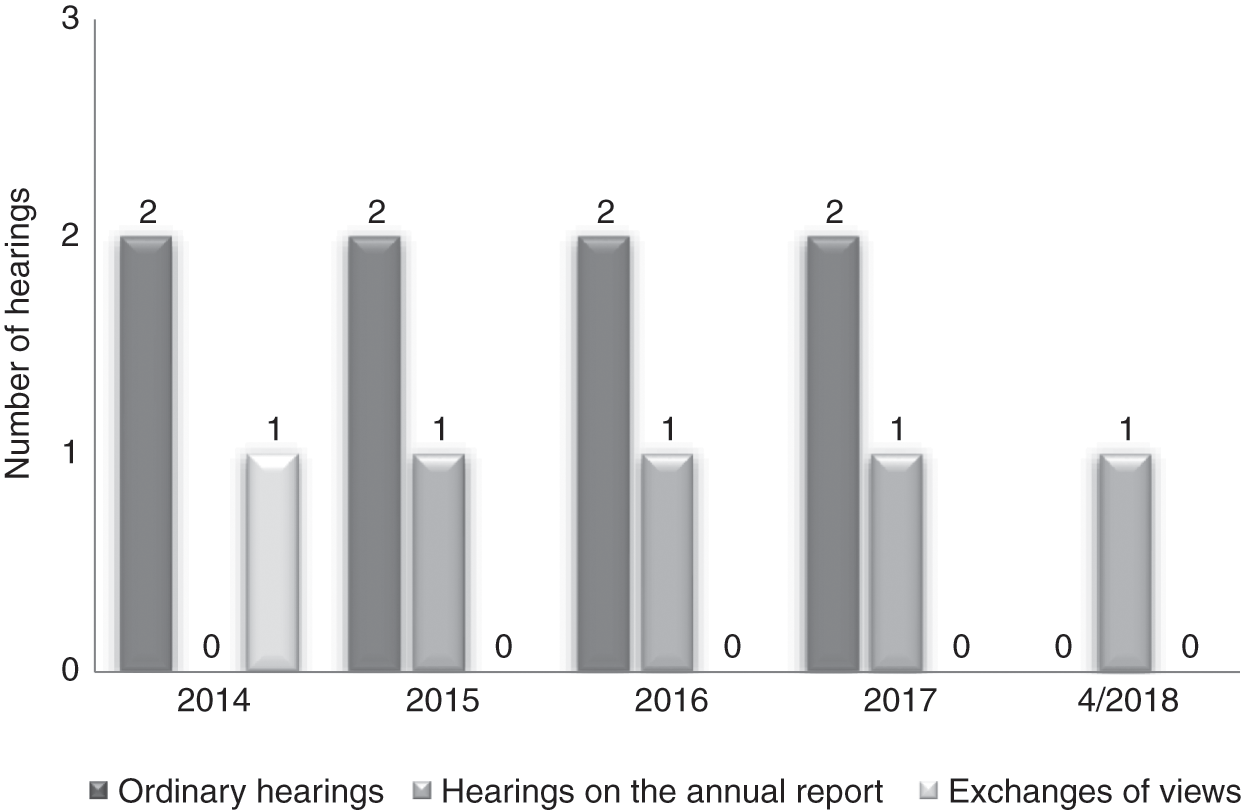

Furthermore, there have been 13 public hearings of the ECB at the ECON Committee during the period January 2014–April 2018, after the first Chair of the Supervisory Board was appointed. Figure 4.2 provides an overview of the type of hearings taking place in the period under focus. Ordinary hearings as well as hearings on the SSM annual report make the bulk of the data. In terms of format, hearings usually last between 90 and 120 minutes and follow a specific structure, starting with (1) welcome announcements by the ECON Chair, followed by (2) an introductory statement by the Chair of the Supervisory Board, and then moving to (3) questions and answers (Q&A) from MEPs. In line with the EP’s Internal Rules of Procedure (European Parliament 2017e), speaking time is allocated in order of the size of political groups and in proportion to their total number of members (Rule 162 for the 8th parliamentary term).

Figure 4.2 Public hearings of the ECB at the EP’s ECON Committee in the SSM framework (January 2014–April 2018)

Using the qualitative data analysis software ATLAS.ti, each single topic question and corresponding answer have been manually coded in line with the analytical approach outlined in Chapter 3.3. Overall, MEPs asked 337 single-topic questions in writing – posing on average 2 questions per letter. In parallel, during hearings, MEPs asked on average 28 questions per session, bringing the total to 369 questions in the period under consideration.

Having established the number of questions raised by the EP to the ECB on banking supervision, the next relevant aspect concerns the profile of MEPs who ask questions.

4.3.1 Profile of Questioners

Who are the MEPs who ask questions of the ECB on banking supervision? In respect of letters, the majority are sent by individual or groups of MEPs from the ECON Committee, although there were four questionnaires sent by the ECON Chair on behalf of the entire committee and one letter sent by the EP President. All political groups sent letters to the ECB on banking supervision, regardless of their size in the EP. As the period under focus overlaps with the 8th parliamentary term (2014–2019), the following political groups were identified (in order of size): the EPP, the S&D, the European Conservatives and Reformists Group (ECR), the Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), the Greens/European Free Alliance (Greens/EFA); the Confederal Group of the European United Left–Nordic Green Left (GUE–NGL); Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group (EFDD); and Europe of Nations and Freedom (ENF).

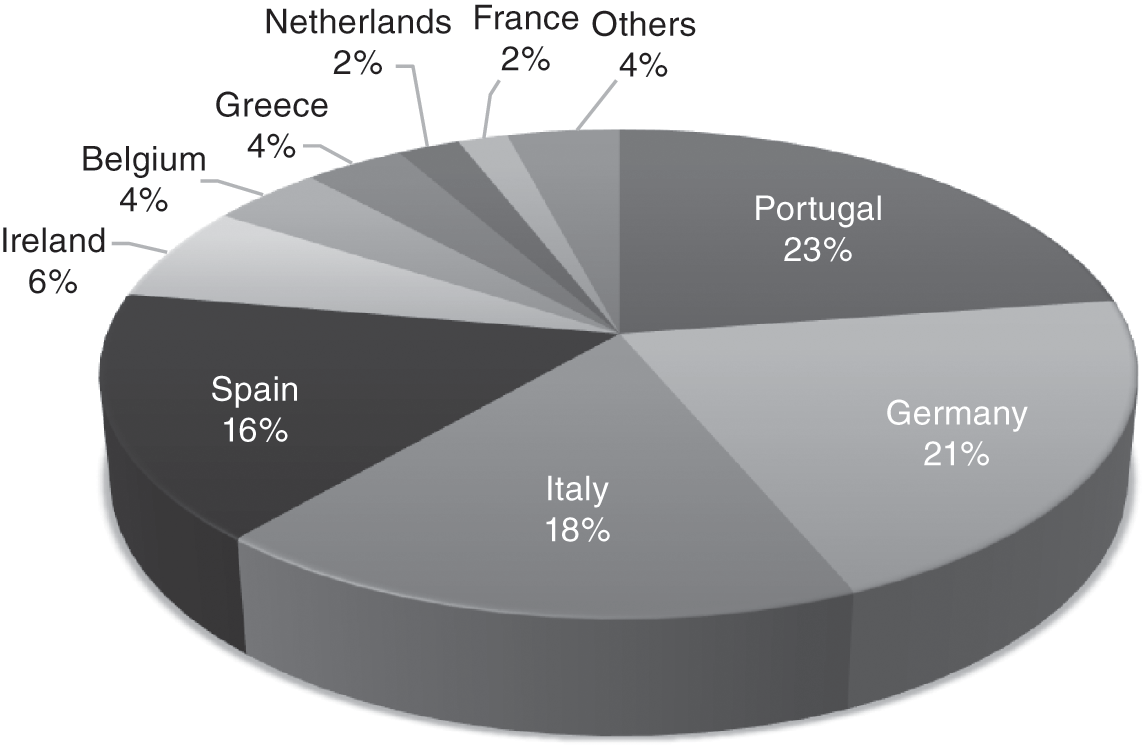

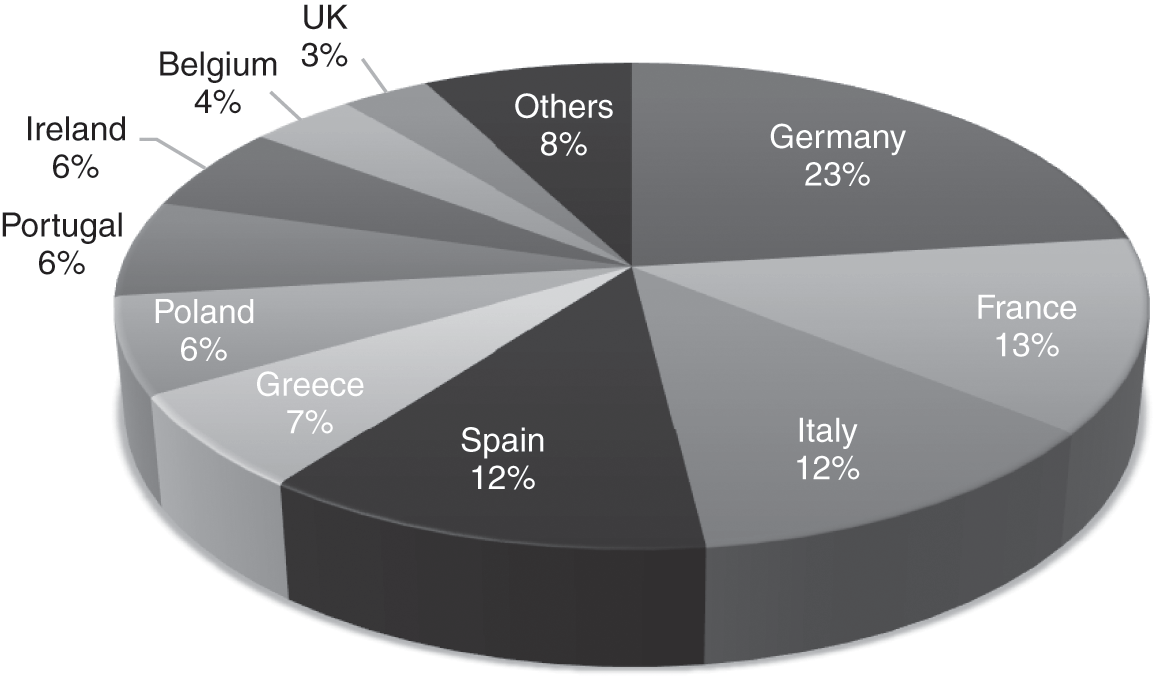

Figure 4.3 captures the nationalities of MEPs asking questions of the ECB on banking supervision in the period under focus. Each MEP is only counted once, regardless of how many questions are posed in a letter. Out of the total 150 letters, 24 letters have multiple authors among MEPs of different nationalities. Overall, most letters are sent by MEPs from Portugal (23%), Germany (21%), Italy (18%), and Spain (16%). When it comes to the content of questions, the national affiliation of MEPs matters more for some members than others: for instance, MEPs from Portugal, Spain, Ireland, and Greece tend to ask questions regarding their own Member States. The others ask more general questions that go beyond their national context, although they also inquire about specific situations in their national or regional constituencies.

Figure 4.3 Nationality of MEPs sending letters with questions to the ECB on banking supervision (October 2013–April 2018). Total: 220 MEPs identified in 150 letters

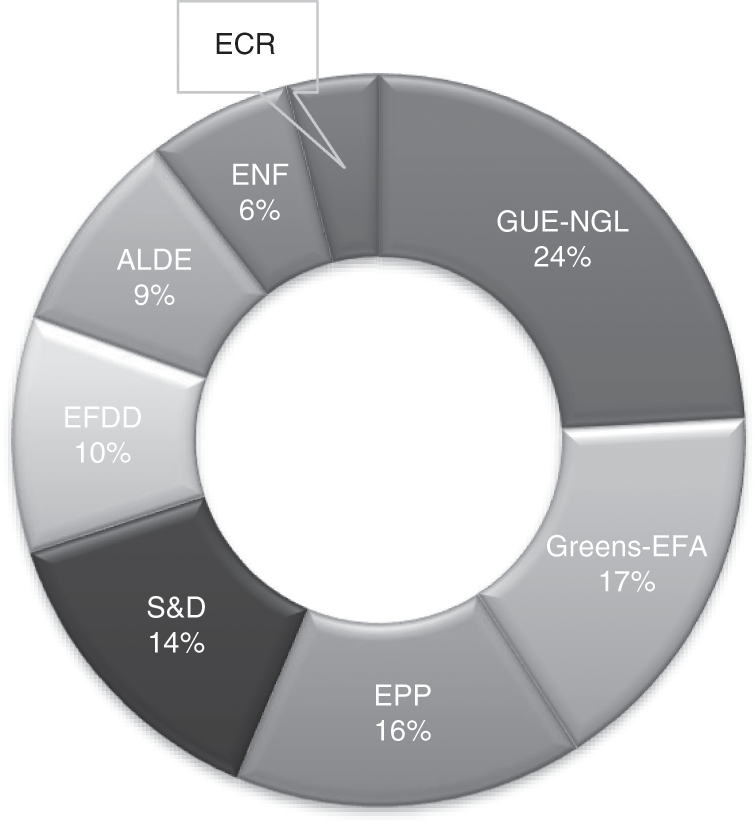

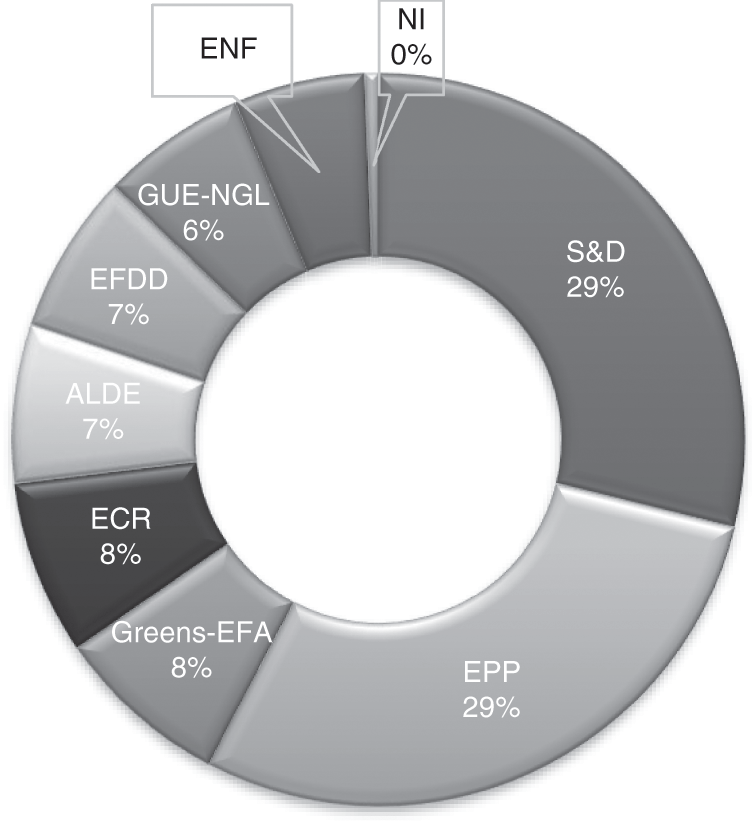

In terms of political affiliation (Figure 4.4), the most active groups were GUE–NGL (24%), the Greens/EFA (17%), the EPP (16%), and the S&D (14%). When letters have multiple authors, they are grouped together by political group. It is important to mention that MEPs from S&D and ALDE tend to send letters in large groups: for example, 30 MEPs from S&D sent 10 letters, while 20 MEPs from the ALDE sent 5 letters. This means that the contribution of smaller groups such as GUE–NGL and the Greens/EFA is underestimated: they send more individual questions to the ECB than larger political groups. A similar dynamic has been found in relation to written questions addressed by MEPs to the ECB in monetary policy (Reference Fraccaroli, Giovannini and JametFraccaroli et al. 2018: 60). Since smaller political groups get less time for questions during committee meetings, letters are a way to compensate for the deficiency, allowing smaller groups to be equally active in oversight. However, the ideological position of MEPs also plays a role, as the two most active political groups in written letters – GUE–NGL and the Greens/EFA – are on the left of the political spectrum.

Figure 4.4 Political affiliation of MEPs sending letters with questions to ECB on banking supervision. Total: 220 MEPs identified in 150 letters

Moving to public hearings, the breakdown of MEPs asking questions by political group and nationality looks different. In respect of nationality (Figure 4.5), German MEPs are leading in public hearings (speaking 23 per cent of the time), followed by MEPs from France (13 per cent), and Italy and Spain (12 per cent each). Keeping in mind that the MEPs who take the floor in public hearings are often the coordinators of political groups in the committees, the statistic is a reflection of the nationality of several ECON Committee coordinators in the 8th parliamentary term for the largest groups, for example, Burkhard Balz (Germany, EPP), Pervenche Berès (France, S&D), Sylvie Goulard (France, ALDE), and Sven Giegold (Germany, the Greens/EFA). Italian MEPs were also consistently active, especially through the contributions of Marco Zanni (EFDD/ENF) and Marco Valli (EFDD).

Figure 4.5 Nationality of MEPs taking the floor during public hearings of the Chair of the Supervisory Board. Total MEPs identified (counted once per session): 156

In respect of political affiliation, the EP’s Rules of Procedure automatically incline the balance towards larger groups (see Figure 4.6). Accordingly, MEPs from the two largest political groups in the 8th parliamentary term – the EPP and the S&D – took the floor most often (each 29 per cent of the time). They were followed by MEPs from the ECR and the Greens/EFA (each 8 per cent of the time). By comparison, smaller political groups get limited speaking time during public hearings, in line with the proportion of their seats in each parliamentary term.

Figure 4.6 Political affiliation of MEPs taking the floor during public hearings with the Chair of the Supervisory Board. Total MEPs identified (counted once per session): 156

Overall, we can observe that MEPs interact frequently with the ECB in the framework of the SSM, both in writing and in person through hearings. Members from smaller political groups on the left (GUE–NGL and the Greens/EFA) tend to send more written questions, while the largest groups (EPP and S&D) dominate the public hearings. In terms of nationality, there is a correlation between the size of a Member State and the number of questions sent by their MEPs, although there are exceptions, for example, Portugal. This is directly related to the problems experienced by Portuguese banks in the period under focus, although by the same logic, we would have expected more questions from Greece – which has the same number of MEPs. The data does not clarify why MEPs from certain Member States tend to be more active; ultimately, this is an empirical question related to the parliamentary tradition of each country and the personal record of MEPs during their term.

In terms of the theoretical expectations outlined in Chapter 3.3.2, the high number of political groups allowed to ask questions and the absence of a government–opposition dynamic vis-à-vis the ECB is bound to limit the strength of parliamentary questions. As MEPs represent a variety of political and national interests, it is by default more difficult to coordinate legislative oversight and ask pointed questions of executive actors. The problem is illustrated in the next section.

4.3.2 Types of Questions

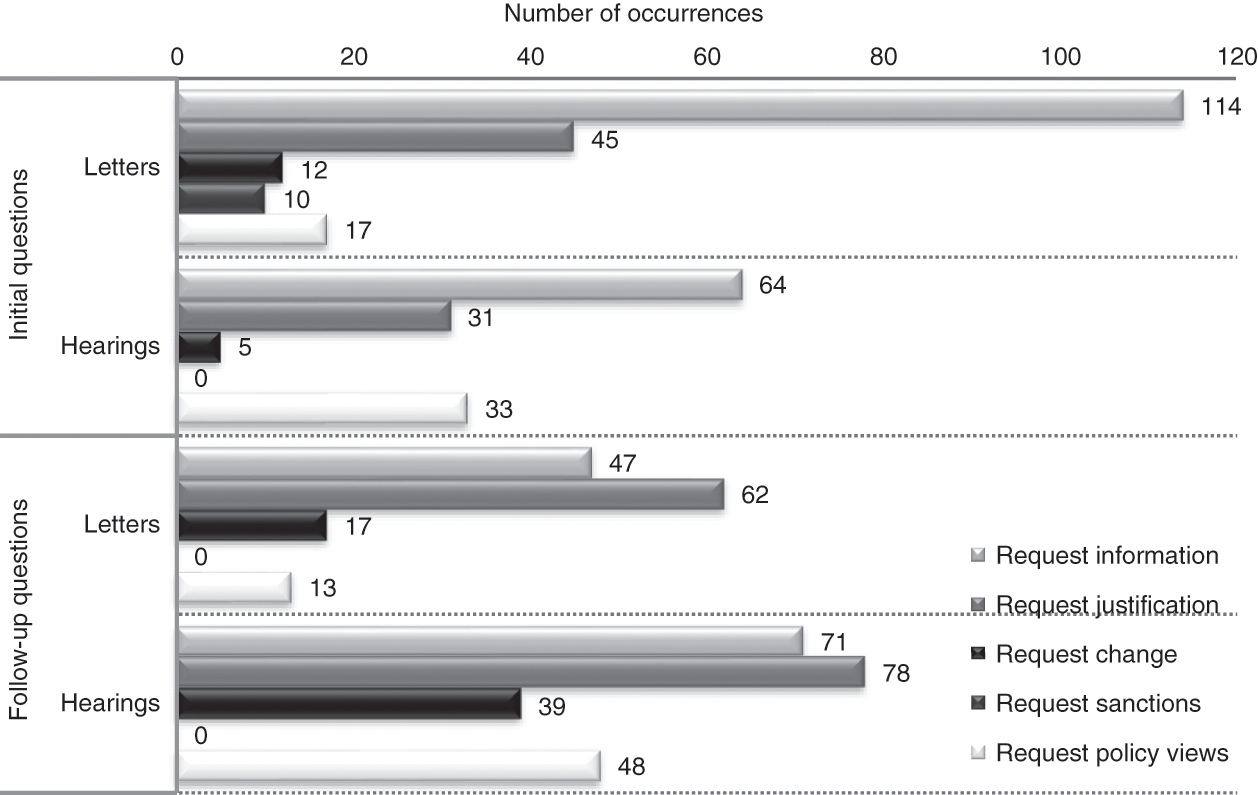

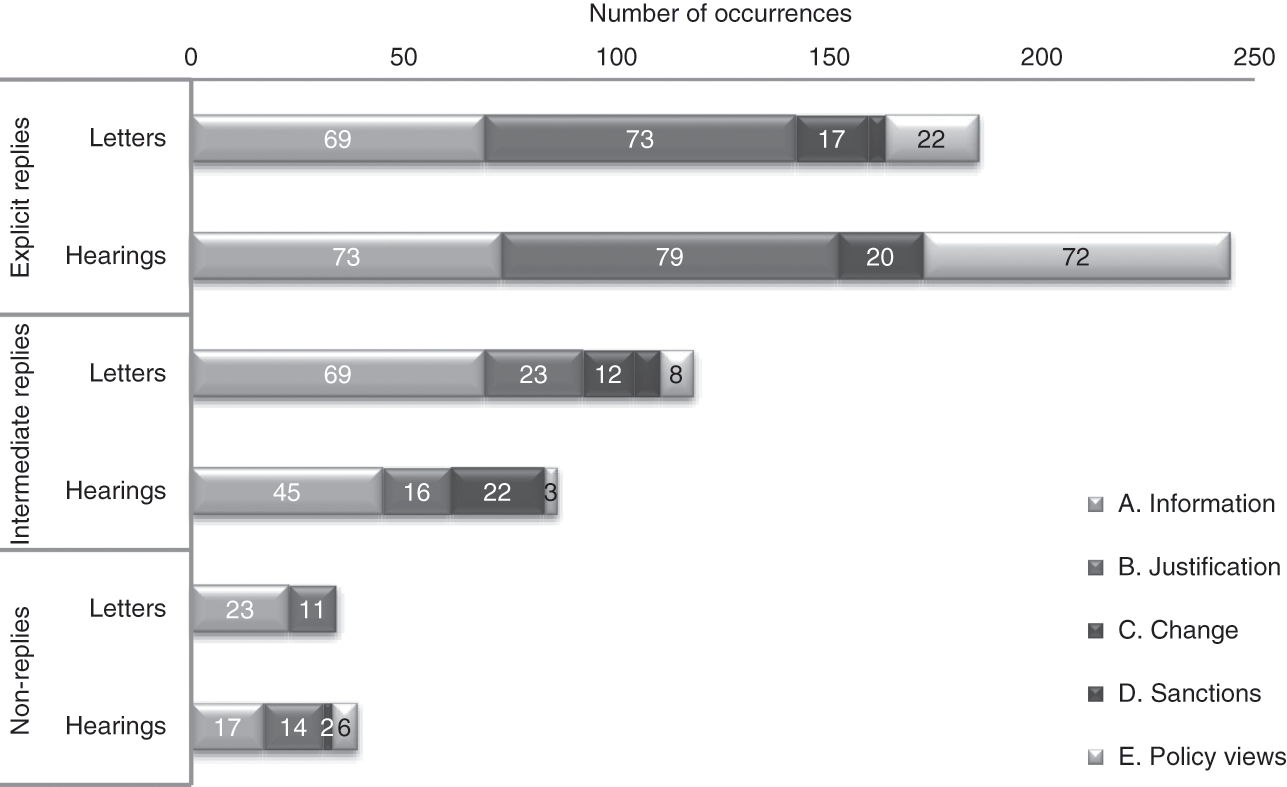

Moving to the subject of oversight, the analysis identified a total of 706 single-topic questions and a corresponding number of answers in both letters and hearings. Following the analytical framework outlined in Chapter 3.3, parliamentary questions were categorised along four types of requests – for information, justification, change of decisions/conduct, and sanctions. Simultaneously, it was possible to distinguish between questions asked for the first time (initial questions) and questions on which MEPs followed up because they were dissatisfied with the original answer (follow-up questions). Given the procedural limitations to asking follow-up questions in EP committees, the analysis grouped together questions on the same issues – even if they were asked by different MEPs. Despite this extension, the number of follow-up questions remains lower, suggesting that MEPs have diverse interests and do not systematically coordinate their oversight of the ECB in banking supervision. Figure 4.7 offers an overview of the types of questions identified in the period under focus.

Figure 4.7 Types of questions asked by MEPs of the ECB on banking supervision (October 2013–April 2018). Total identified: 706

There are several observations coming out of the figure. First, there is a fifth category of questions that falls outside the scope of oversight interactions. This refers to ‘requests for policy views’ – present in 111 out of the 706 total questions. Such requests typically include demands for the ECB’s expert opinion on ongoing legislative files or issues relevant to Member States domestically. While it makes sense for MEPs to consult the ECB on their legislative activity, this can be done separately and not filed under accountability. In fact, the ECB is formally consulted on proposed EMU legislation more generally (European Central Bank 2021b). Requests for policy views cannot be considered a form of oversight because they do not concern the past activity of the ECB in terms of decisions or conduct. Conversely, they typically refer to the future legal framework of the banking union. Requests for policy views are more common during hearings (22 per cent of all questions asked) than in letters (8.9 per cent of all questions sent), with the additional observation that rapporteurs on legislative proposals are most likely to use hearings with the Chair of the Supervisory Board to ask for input on files within their purview. From this perspective, it appears that a fifth of all questions in hearings are wasted on issues that have nothing to do with accountability.Footnote 16

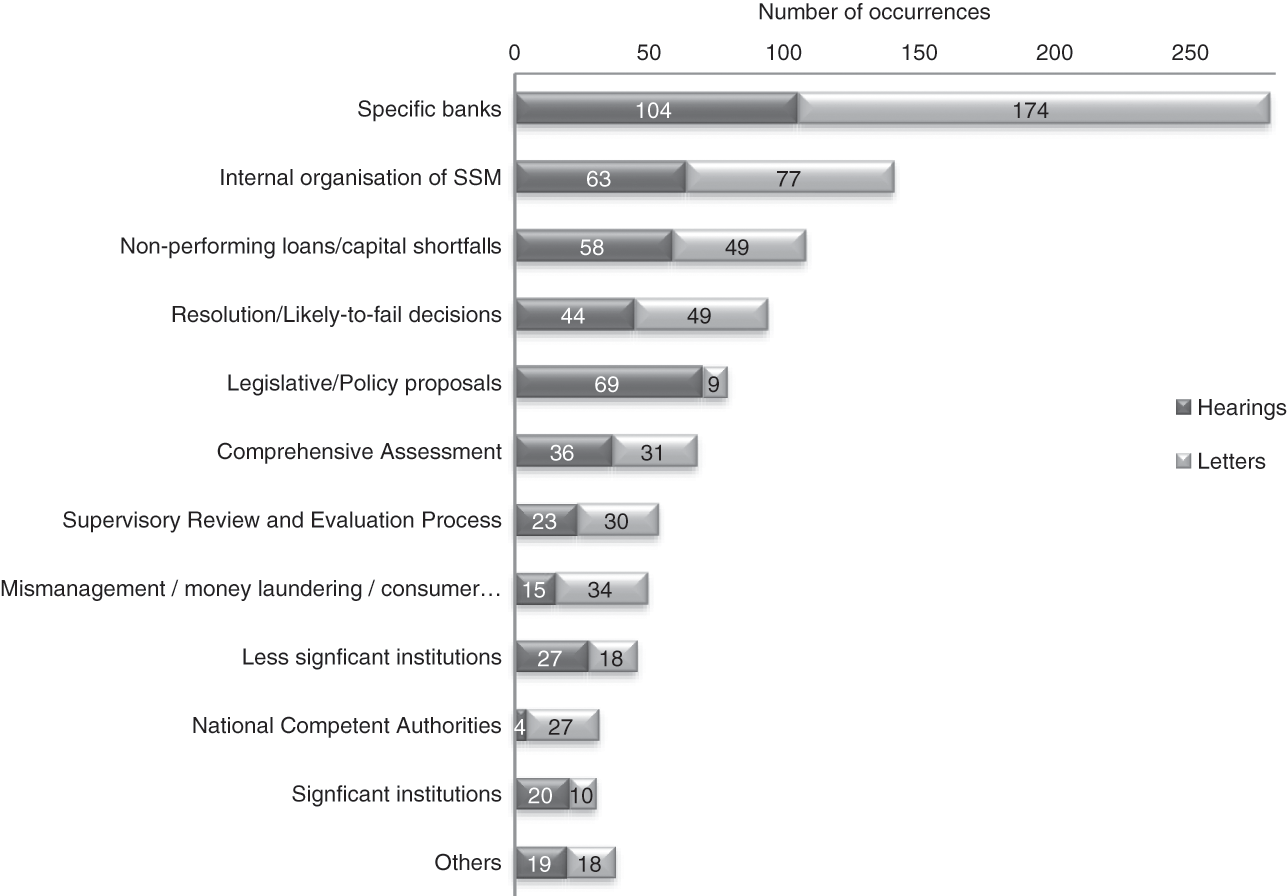

Furthermore, the most prevalent types of questions in both letters and hearings are requests for information (49.7 per cent overall) and justification of conduct (36.3 per cent overall). This is not surprising, considering the institutional independence of the ECB and the lack of political mechanisms to demand changes of decisions or impose sanctions (see Section 4.2). Moreover, since the SSM was only established in 2013–2014, many questions addressed the internal organisation of the ECB in banking supervision and the 2014 comprehensive assessment. However, the most popular subject of questions by far refers to the situation at specific banks under the direct or indirect supervision of the ECB (Figure 4.8).

Figure 4.8 List of topics raised in hearings and letters to the ECB on banking supervision (October 2013–April 2018). One question can have one or two codes. Total codes assigned: 1,009 for 706 questions

Banks that attract the most attention are usually those that performed poorly in stress tests and had a high level of non-performing loans (NPLs), such as the Italian banks Monte dei Paschi di Siena, Banco Populare de Vicenza, and Veneto Banca. Other examples include banks that were formally declared failing or likely to fail (FOLTF) (e.g. the Spanish Banco Popular) or alternatively were considered to receive preferential treatment in stress tests (e.g. the German Deutsche Bank). MEPs also ask many questions about the resolution of less significant institutions (e.g. the Portuguese bank Banif) or the re-capitalisation of state-owned significant banks with the approval of the Commission (e.g. the Portuguese bank Caixa Geral de Depósitos). Unsurprisingly, these are also the banks that are most often mentioned in press reports regarding the performance of the SSM. However, given the professional secrecy requirements laid down in the Interinstitutional Agreement between the EP and the ECB and in the CRD IV, the ECB ‘cannot comment on the interactions with individual supervised institutions or on the supervisory measures taken with regard to them’ (Reference NouyNouy 2016a). There is thus a tension between the issue that MEPs care most about – the next one is ‘SSM internal organisation’ (see Figure 4.8) – and the likelihood that they will receive the information they publicly seek. Holding the ECB accountable in banking supervision is bound to be limited from the outset.

Moreover, follow-up questions are more likely to occur in hearings (65.3 per cent of all questions) than in letters (41 per cent of all questions raised). This happens because some hearings have a central topic that dominates the Q&A session. In the period under focus, there were three instances of hearings with ‘heated’ debates: (1) in November 2016, in relation to the methodology of stress tests and the alleged preferential treatment of Deutsche Bank thereof; (2) in June 2017, on the recent decision to declare Banco Popular FOLTF; and (3) in November 2017, when MEPs contested the draft Addendum to the ECB Guidance on NPLs (the Addendum) as overstepping the institution’s mandate (see below).

The Deutsche Bank case received a lot of attention in both oral and written questions. In short, the problem was that in the 2016 stress test, the ECB accepted in the assessment of Deutsche Bank the sale of its stake in the Chinese bank Hua Xia, even though the transaction was going to be completed at the end of the year and the stress test took place in the summer. There were nine letters asking the ECB for the reasoning behind its agreement to ‘bend the rules’ for Deutsche Bank. The questions share common ground, as MEPs referenced or copied text directly from a Financial Times article reporting the ECB’s preferential treatment in this case (Reference Noonan, Binham and ShotterNoonan et al. 2016). The Chair of the Supervisory Board defended the decision, explaining that the conclusion of the transaction was regarded as a mere formality (it was concluded by the end of the year). In addition, Deutsche Bank formally requested the exception; by comparison, other banks claiming to be in a similar position did not request such an exception. In response to the nine letters, the ECB provided an almost identical text, with large portions of the reply copy-pasted from the first answer offered. Judging from the follow-up questions in the November 2016 hearing, many MEPs did not accept the ECB’s answers as valid. The point here is that MEPs are eager to challenge ECB supervisory decisions, but there are only a few cases in which they have the background information and knowledge to do so.

The case of the Addendum also deserves further attention – not least because it was the subject of a letter sent by the EP President to the ECB. This is also the main clear-cut example of MEPs demanding concrete changes to the ECB’s conduct. The Addendum aimed to address one of the most persistent and controversial problems in banking supervision, namely how banks should deal with high levels of NPLs on their balance sheets. The document was designed to supplement the earlier ECB Guidance on the matter by specifying minimum levels of prudential provisions for new NPLs starting 1 January 2018 (European Central Bank 2017). Several Members of the ECON Committee, after asking the opinion of the EP’s Legal Service, challenged elements of these supervisory expectations as ultra vires because they effectively introduced additional obligations for banks beyond the current regulatory framework. At the same time, MEPs considered that the ECB did not give legislators and the public sufficient time to provide feedback on the Addendum, as its date of entry into force was less than three months from the publication of the draft version. Nouy acknowledged during the hearing that the phrasing of several provisions could be improved, as the meaning seems to have been misunderstood from what the ECB had intended. One example is the so-called comply or explain mechanism, criticised for inverting the burden of proof from the supervisor to the supervised bank, with the implication that banks would become responsible for showing that their provisioning level was adequate instead of the supervisor demonstrating that it was inadequate. This was changed in the revised version of the Addendum, whose date of entry into force was also postponed to 1 April 2018 (European Central Bank 2018: 7). The case is an example of the effective performance of the EP as an accountability forum when there is a clear, coordinated agenda about what to ask from the ECB on banking supervision. The pressure put by MEPs asking questions on the same issue, even if sometimes they were repeated, is something to bear in mind for improving future hearings of the ECON Committee.

Overall, the questions asked by MEPs to the ECB on banking supervision paint a layered picture of the EP’s performance as an accountability forum. At the outer layer, the track record of MEPs in holding the ECB accountable is underwhelming: too often their questions demand policy views or contest issues that the ECB cannot fully address due to the legal framework to which the EP contributed. But the inner layer brings nuance to the picture: there are structural problems – especially confidentiality requirements – that make it difficult for MEPs to receive answers to the questions they find important. The next section shifts the attention from the accountability forum to the actor, examining the ranges of answers provided by the ECB on banking supervision.

4.3.3 Types of Answers

The ECB is legally required to reply to written and oral questions from MEPs in the framework of their accountability relationship in the SSM. However, there is a difference between answering questions as a procedural requirement and engaging with the substance of the issue raised. Requests for policy views are almost always answered fully: as a specialised public body, the ECB is happy to share its expertise on different matters of banking supervision. However, for the purposes of legislative oversight, what matters are answers to requests A–D, which are discussed in the next pages.

Figure 4.9 lists the number of answers identified as explicit replies, intermediate replies, and non-replies in the period under investigation. At first sight, the overview of answers shows the high responsiveness of the ECB to EP oversight. On the whole, the ECB provides explicit replies in response to almost two thirds of all questions received in the SSM framework (429 out of 706 answers), showing the willingness of the institution to engage with the questions raised by MEPs. However, when calculated as a percentage of all questions (excluding the irrelevant requests for policy views), answers that count as explicit replies only make up 47.45 per cent of the total. Figure 4.9 shows the breakdown of ECB answers in both letters and public hearings.

Figure 4.9 Types of answers provided by the ECB on banking supervision to MEPs, in numbers (October 2013–April 2018). Total answers identified: 706

When it comes to explicit replies (identified 429 times), most answers provide information (33.1 per cent) or justification of conduct (35.4 per cent). In relation to questions of type A, explicit replies (142 overall) can offer full information about decisions (policy transparency) or decision-making processes (procedural transparency). In response to questions of type B, there is a clear tendency for the ECB to justify its conduct or explain the rationale behind decisions (on 152 occasions). Although there are fewer explicit replies given in response to type-C questions (8.6 per cent), the number is consistent with the total amount of requests for change (10.3 per cent of all questions). In respect of sanctions, these were no longer necessary in three instances (because the responsible parties had already resigned), while on one occasion, the ECB rejected the need for sanctions.

The next category includes intermediate replies (identified in 204 instances), where the majority of answers (55.9 per cent) addressed requests for information. One example is partial or incomplete answers which engage with some elements of the question raised or talk about the topic in general terms, without going into specifics. Other types of intermediate replies promise to provide information or justification of conduct at some point in the future, based on ongoing developments. The answer is legitimate but dependent on follow-up questions that may or may not be raised by MEPs. Finally, intermediate replies can acknowledge the topic of a question but claim the ECB’s lack of competence on the matter and refer the EP towards another actor deemed responsible (see discussion on equivocation below).

The final category of answers is made of non-replies and was identified on 73 occasions. Non-replies are answers in which the ECB avoids or openly refuses to respond to issues raised by MEPs. Here, there is a difference between written and oral questions, as the lack of answers in letters is supported by confidentiality requirements of the SSM legal framework, while non-replies in hearings are an example of evasion – that is, not addressing the substantive point of a question. In the case of the latter, it is difficult to identify ill-intent: most often, the Chair of the Supervisory Board simply spends more time covering one question and does not have time for the others.

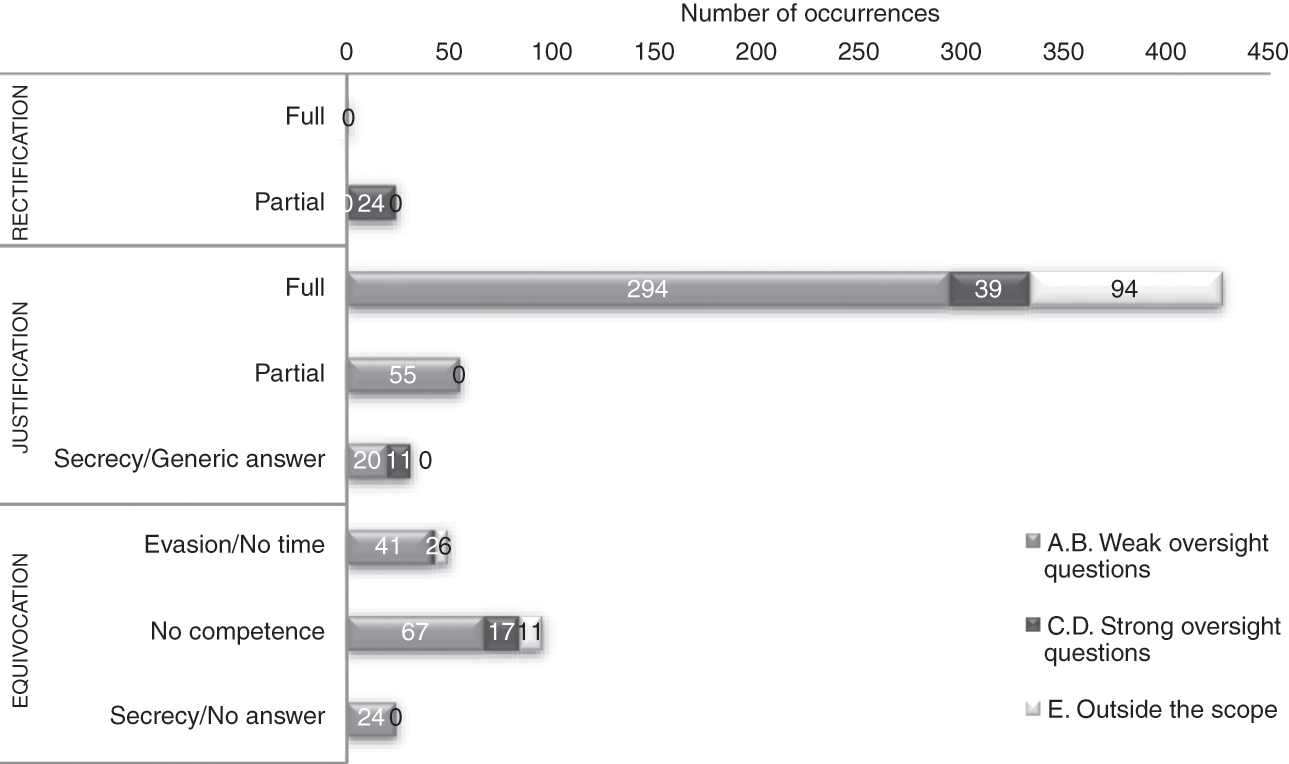

Having established the main types of replies provided by the ECB on banking supervision, the next step is to examine how they engage with parliamentary questions from MEPs. Figure 4.10 illustrates the categories of answers given through ‘rectification’, ‘justification’, and ‘equivocation’ in the period under focus. The first observation coming out of the table is that the ECB rarely changes its conduct in response to demands from MEPs; in fact, the only instance when the Chair of the Supervisory Board engaged with requests for policy change coming from MEPs concerned the Addendum (see Section 4.3.2). During hearings at the ECON Committee, the Chair of the Supervisory Board acknowledged the lack of clarity regarding the Addendum’s ‘comply-or-explain’ mechanism and considered the possibility of postponing the document’s entry into force. This was, however, an isolated case (present in 24 partial answers). Conversely, the majority of questions addressed to the ECB on banking supervision are answered through justification, providing full or partial information about a particular issue, explaining the rationale of decisions, or defending the appropriateness of a measure. The proportion of answers marked as ‘full’ as opposed to ‘partial’ justification (427 vs 55) speaks to the engagement of the ECB with parliamentary questions.

Figure 4.10 Responsiveness of the ECB on banking supervision to MEPs in both letters and hearings (October 2013–April 2018). Total answers identified: 706

What are the questions that go unanswered? Equivocated replies are answers that do not offer MEPs substantive responses to the questions they raised. There are three categories of replies identified here. First, there are generic answers that come across as evasion or questions not answered due to time considerations, which were identified on 49 occasions. These correspond to non-replies in Figure 4.9 and have been discussed above. Second, intermediate replies that claim ‘lack of competence’ are usually seen as problematic in accountability studies because they suggest the passing of responsibility from one executive actor to another (Reference HoodHood 2010). On banking supervision, such answers occur when the ECB claims that certain issues are within the purview of NCAs or lie outside its mandate in banking supervision (95 in total). These answers are given in response to questions on (1) the methodology of stress tests, especially the choice of adverse scenarios, for which the EBA and the European Systemic Risk Board are responsible; (2) the resolution process of specific banks, where the SRB and/or the European Commission have competence; (3) issues of consumer protection – especially concerning unfair practices of banks – where national bodies have jurisdiction; and (4) cases of financial misconduct and money laundering in different member states, where national authorities are also the competent institutions.

The high frequency of such questions is the result of the intricate multi-level framework of the banking union, where the division of tasks is spread across many institutions at different levels of governance. Separating bank regulation (EBA) from bank supervision (ECB) and bank resolution (the SRB and the Commission) created overlapping areas of activity that remain difficult to disentangle from an accountability perspective. At the same time, the fact that the SSM mandate is limited to prudential supervision and hence does not include matters such as consumer protection or money laundering additionally complicated matters because it restricts the range of issues for which the ECB can be held accountable. It is difficult to establish whether MEPs ask questions outside the ECB’s supervisory competence unknowingly or on purpose – because they are important to their constituencies. As a general pattern, it seems that many MEPs base their questions on current financial news in the national or international media, which suggests an interest in politically salient issues that is disconnected from considerations of the relevant competent authority.

Nonetheless, not all cases are straightforward when it comes to the ECB’s lack of competence. For instance, in the first report on the functioning of the SSM, the Commission discretely criticised the ECB for pointing the finger at the EBA regarding the flaws of stress tests methodologies, keeping in mind its own responsibility for the quality of the process (European Commission 2017). Another relevant example concerns the Portuguese bank Banif, a less significant institution under the supervision of Banco de Portugal, which was put into resolution in December 2015. The controversy concerned the ECB’s approval to limit Banif’s access to Eurosystem liquidity prior to the announced decision that the bank was FOLTF, as well as the involvement therein of ECB Vice-President Vítor Constâncio, who was the former Governor of Banco de Portugal. In the following year, Portuguese MEP Nuno Melo (EPP) sent 12 letters to the ECB demanding information and justification of conduct about the ECB’s role prior to and during the FOLTF decision-making process (European Parliament 2016f). On the supervisory part, the SSM Chair repeatedly invoked lack of competence and directed the MEP towards Banco de Portugal as the ‘right addressee’ for the questions (Reference NouyNouy 2016b). The point here is that the banking union established a convoluted system: it is not always clear who bears responsibility for specific actions or how to differentiate ‘real’ lack of competence from passing the buck from one institution to another.

The other type of equivocated answer that deserves close attention refers to non-replies given on confidentiality grounds, present on 24 occasions. Such answers concern questions that require information or justification of decisions regarding a specific supervised bank. In the early years, the ECB would address such requests by invoking its confidentiality regime and offering no answer whatsoever. Over time, the SSM Chair started to provide general considerations about the bank in question and what the ECB did under similar circumstances for any supervised bank. This allowed an answer to be provided without revealing what is considered sensitive supervisory information on specific banks. Such instances are marked in Figure 4.10 as ‘justification’ – invoke ‘secrecy generic answer’ in order to distinguish them from replies where no answer was given at all (illustrated under ‘equivocation – invoke secrecy’). When confronted with questions about the legitimacy of the ECB secrecy regime, the Chair of the Supervisory Board answered as follows:

These [confidentiality] requirements, as adopted by the European EP and/or the Council of the European Union, form the cornerstone of the legal supervisory framework under which European banking supervision operates. They are aimed at instilling confidence in credit institutions that the banking supervisor will treat their sensitive information appropriately. This is essential for an open supervisory dialogue and thus an important basis for effective banking supervision.

Invoking confidentiality requirements means that parliamentary questions are dealt with expediently and unsatisfactorily from the perspective of an accountability forum. While some MEPs ask multiple rounds of questions about the same bank, they give up at some point and move on to different issues – aware that there is nothing they can legally do to force the ECB to provide public information or justification.

The importance of the secrecy regime is interpreted differently by the ECB. According to one official, ‘what is observable by the public is the non-confidential part. But there are several possibilities to exchange [information] on a confidential basis’, such as the routine in-camera meetings before hearings of the Chair of the Supervisory Board or the (as-yet-unused) formal confidential oral discussions and inquiry committees. Moreover, from the perspective of the ECB, such questions remain important even if they cannot reply with bank-specific information: ‘On the one hand, it helps us understand the thinking of MEPs and on the other hand it may allow us to clarify our general policies which are of relevance to the specific case.’Footnote 17

Ultimately, the problem of the ECB’s confidentiality requirements can be solved in two ways: either the two institutions agree on a change in the legal framework that would allow the EP to receive answers to politically salient questions, or MEPs must alter the type of questions they send to the ECB on banking supervision. Information about specific banks is at the heart of banking supervision because it concerns the way in which SSM rules are enforced; for this reason, it can be expected that the EP will continue to ask such questions in the future even if they will rarely receive full answers in response.

4.4 The Record: Holding the ECB Accountable in Banking Supervision

The early years of the functioning of the SSM institutionalised the accountability relationship between the EP and the ECB in banking supervision. As noted by the ECB Annual Reports on the SSM, the two institutions interact on a regular basis through hearings and letters. MEPs ask the Supervisory Board numerous oral and written questions, to which the ECB replies in a timely manner. Going back to the variables expected to have a positive effect on parliamentary questions (Chapter 3.3.1), this means that the EP has multiple structural opportunities for oversight in banking supervision. More specifically, MEPs can interact directly with the Chair of the Supervisory Board in a single committee (ECON) every couple of months and can ask written questions of the ECB at any time. Moreover, the aspect of high public pressure mentioned in the analytical framework is present in banking supervision in respect of the results of stress tests or if a bank is declared FOLTF. Whenever such events are covered by the media, the number of follow-up questions to the ECB increases in a corresponding manner. By contrast, the institutional characteristics of the EP – the emphasis on law-making and the high number of political groups – have a negative effect on the strength of parliamentary questions. This is visible in the significant number of requests for policy views on legislative dossiers as well as in the diversity of questions addressed by MEPs across political groups. Overall, MEPs from Portugal, Germany, Italy, Spain, and France ask the bulk of questions, while smaller political groups on the left tend to be more active.

In terms of the substance of questions, the analysis identified multiple examples outside the scope of oversight or related to issues that went beyond the ECB’s competence in banking supervision. In line with the analytical framework of Chapter 3.3, the majority of questions were ‘weak’, focused on demands for information and justification of conduct. The problem, however, turned out to be systemic – rooted in the strict confidentiality regime that protects supervised banks and ensures that the ECB does not disclose sensitive information about supervisory decisions. This is in line with the expectation regarding the level of asymmetric information in principal–agent relations (Chapter 3.3.2): in this case, the underlying accountability deficit is the inability to assess the performance of the ECB in banking supervision in the absence of information about the specific decisions taken. Other authors have already noted the lack of a clear yardstick to measure whether the ECB is achieving its mandate in the SSM (Reference Amtenbrink and MarkakisAmtenbrink and Markakis 2019; Reference BraunBraun 2017: 7). To put it differently, if the ECB is doing a good job in banking supervision, how would MEPs – and the public at large – know it?

For its part, the ECB engaged openly with parliamentary questions, as most answers identified were explicit or partial/intermediate replies. The more important finding is the focus on justification rather than rectification, which suggests that the ECB is willing to explain and defend the rationale of its decisions on banking supervision, but it would rarely accept policy changes in response to EP oversight. In relation to the scenarios for legislative oversight outlined in the analytical framework, the dynamic puts the relationship between the EP and the ECB in banking supervision in ‘Transparency’ (scenario 4) – reflecting a higher proportion of ‘weak’ oversight questions and an emphasis on answers through justification (see Chapter 3.3.1). Nevertheless, the caveat remains the secrecy regime outlined above. The only time the ECB changed its decisions as a result of EP oversight occurred when MEPs across political groups acted together and on the basis of advice from the EP Legal Service, which provided evidence that specific ECB measures went beyond the tasks delegated to the institution in banking supervision. As in other cases of political oversight of bureaucratic actors or independent agencies, there is a clear imbalance between the expertise of the EP and that of the institution they are supposed to hold accountable. The EP’s Economic Governance Support Unit (EGOV) has partially helped in this respect by preparing background notes before every public hearing of the Chair of the Supervisory Board. But the problem of asymmetric information will continue to characterise oversight interactions between the ECB and the EP.

In the future, the ECB will be considered accountable to the EP in banking supervision depending on the way in which the next Chairs of the Supervisory Board will substantively answer questions from MEPs. While the ECB is not expected to comply indiscriminately with requests from the EP and thus be ‘responsive’ to a political forum, it should stand ready to explain and defend its conduct in the SSM – and thus come closer to scenario 2 of legislative oversight interactions, namely ‘Answerability’ (see Chapter 3.3.1). The book’s analytical framework had higher expectations for the EP’s accountability relationship with the European Commission, which were similarly unfulfilled – as shown in the next chapter.