This book examined the effectiveness of the EP as an accountability forum that oversees EU executive actors on a day-to-day basis. The policy area under focus was the EMU – a politically sensitive field whose salience at the EU level increased significantly as a result of the euro crisis. Debates about the accountability of EMU executive actors included controversial issues such as the fairness of austerity measures, the need for solidarity between countries, divisions between North and South, the stability of the Eurozone banking system, the importance of equal treatment of the Member States, the dominance of national executives in EU decision-making, and so forth. Owing to its transnational composition and European profile – as the only directly elected institution at the EU level – the EP showed great promise to hold executive actors accountable for collective decisions that affect the EU as a whole. Against this background, the book explored four case studies of EP oversight of EMU executive actors, namely the ECB, the Commission, the ECOFIN Council, and the Eurogroup, respectively. Notwithstanding small variations dependent on the date when EP oversight was established, all cases covered the period during and/or after the euro crisis (2010–2019).

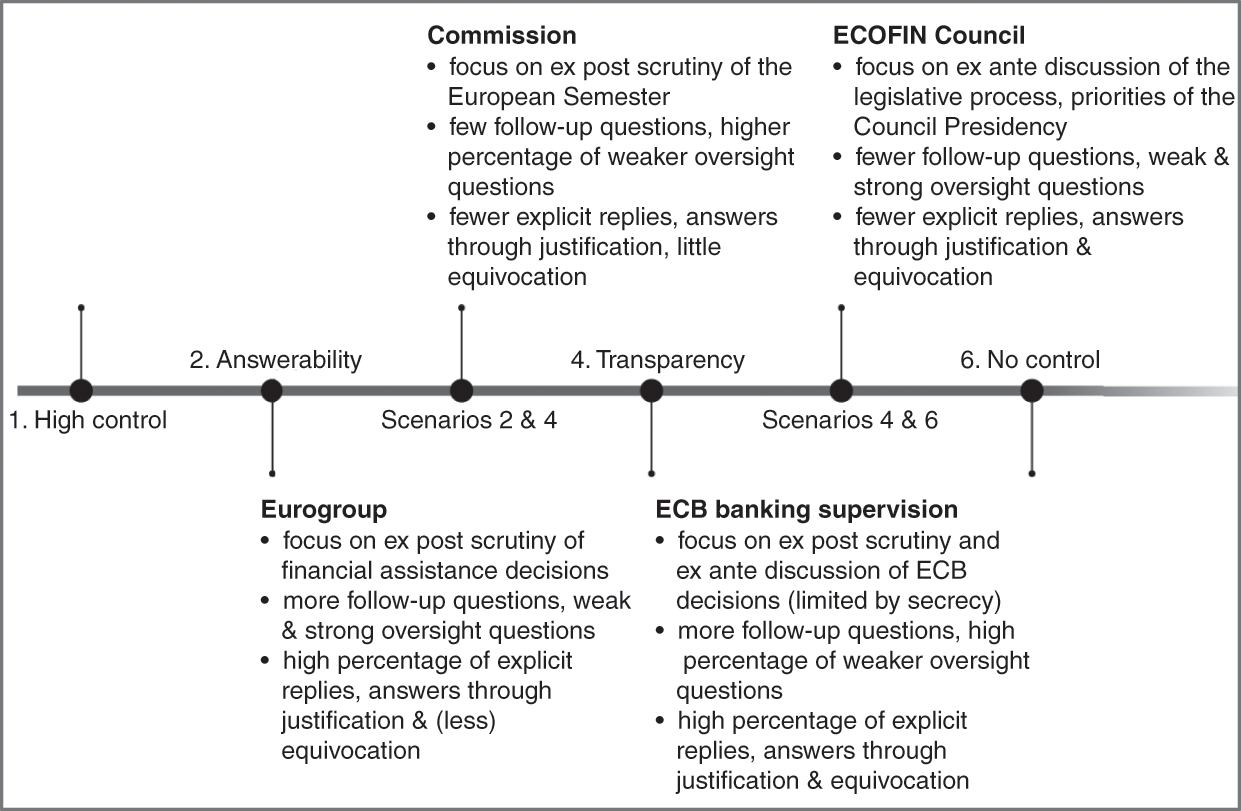

The conclusion consists of three parts. The first section compares the oversight interactions between the EP and the four institutions discussed throughout the book. Based on the analytical framework described in Chapter 3.3, the findings show that the EP has the strongest accountability record in the EMU vis-à-vis the Eurogroup, followed by the Commission, the ECB in banking supervision, and finally the ECOFIN Council. But there are important limitations even in the case of the Eurogroup, which is answerable but not responsive to EP oversight. In other words, the EP can make the Eurogroup justify its conduct but cannot control its decisions or change the direction of existing policies. Moreover, the EP’s oversight interactions with the other institutions display different problems. In the accountability relationship with the Commission, MEPs ask few follow-up questions and generally put less pressure than on the Eurogroup. When overseeing the ECB, MEPs are willing to be confrontational on multiple topics but face structural obstacles such as the secrecy regime in banking supervision and the ECB’s institutional independence. Finally, in interactions with ECOFIN, the EP focuses on influencing legislative decision-making rather than overseeing executive measures adopted by the Council. Based on the scenarios of legislative oversight specified in the analytical framework (Chapter 3.3.1), the four case studies are correspondingly positioned on the continuum from ‘High control’ to ‘No control’ by the EP.

The second section is forward-looking, outlining ways to improve the performance of the EP as an accountability forum and increase the responsiveness of executive actors in the EMU. The idea is to provide concrete policy recommendations for both the EP and EMU executive actors, in line with the accountability purposes emphasised in the analytical framework. The final section situates EP oversight in the broader context of EU accountability and democratic legitimacy. Despite the fact that the EP is only one piece of the puzzle of EU accountability, its scrutiny powers can undoubtedly contribute to bridging the gap between citizens and executive actors in the EU political system.

7.1 Case Comparison

The findings of previous chapters reveal a nuanced picture of oversight interactions in the EMU. In order to facilitate the analysis, the comparison below focuses on the percentagesFootnote 27 of questions and answers identified across the four cases. The discussion starts with the types of questions asked by the EP as an accountability forum, followed by a description of the answers provided by executive actors, and finally an assessment of the cases in relation to the six scenarios of oversight interactions outlined in the analytical framework.

7.1.1 The Performance of the EP as an Accountability Forum

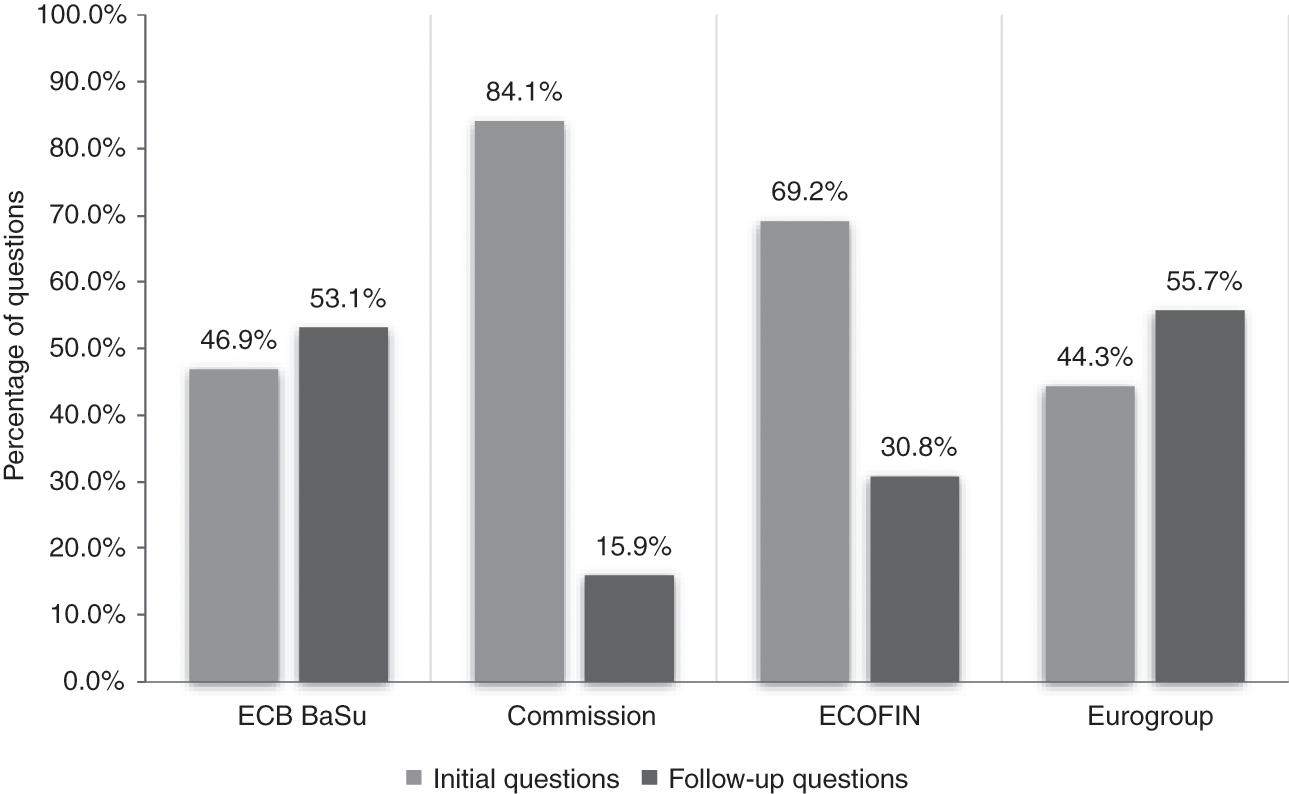

Figure 7.1 provides an overview of the share of initial and follow-up questions posed by MEPs to the ECB, the Commission, the ECOFIN Council, and the Eurogroup in the case studies analysed in the book. As a reminder, follow-up questions can be asked by MEPs from different political groups, keeping in mind that EP Rules of Procedure have strict time limitations for oral questions posed by the same member. Examining the four data sets side by side, we can see clearly that there are more follow-up questions addressed to the Eurogroup and the ECB on banking supervision than to the ECOFIN Council or to the Commission. In fact, only 15.9% of the questions posed to the Commission are follow-ups, which suggests a lower intensity of oversight. MEPs ask the Commission numerous questions, but these are unrelated – illustrating the diverse interests of Member States and political groups represented in the EP. A similar dynamic can be found vis-à-vis the ECOFIN Council, albeit with a higher number of follow-up questions (30.8% of all questions identified). By contrast, MEPs ask more follow-up questions of the ECB on banking supervision (53.1%) and the Eurogroup (55.7%), revealing an overlap of interests from MEPs regardless of national or political affiliation. To put it differently, the EP is more likely to push the ECB on its supervisory decisions or the Eurogroup on financial assistance than it is to press the Commission on the European Semester or the ECOFIN Council on ongoing legislative files.

Figure 7.1 Percentage of initial and follow-up questions posed by MEPs to each institution, based on Chapters 4–6

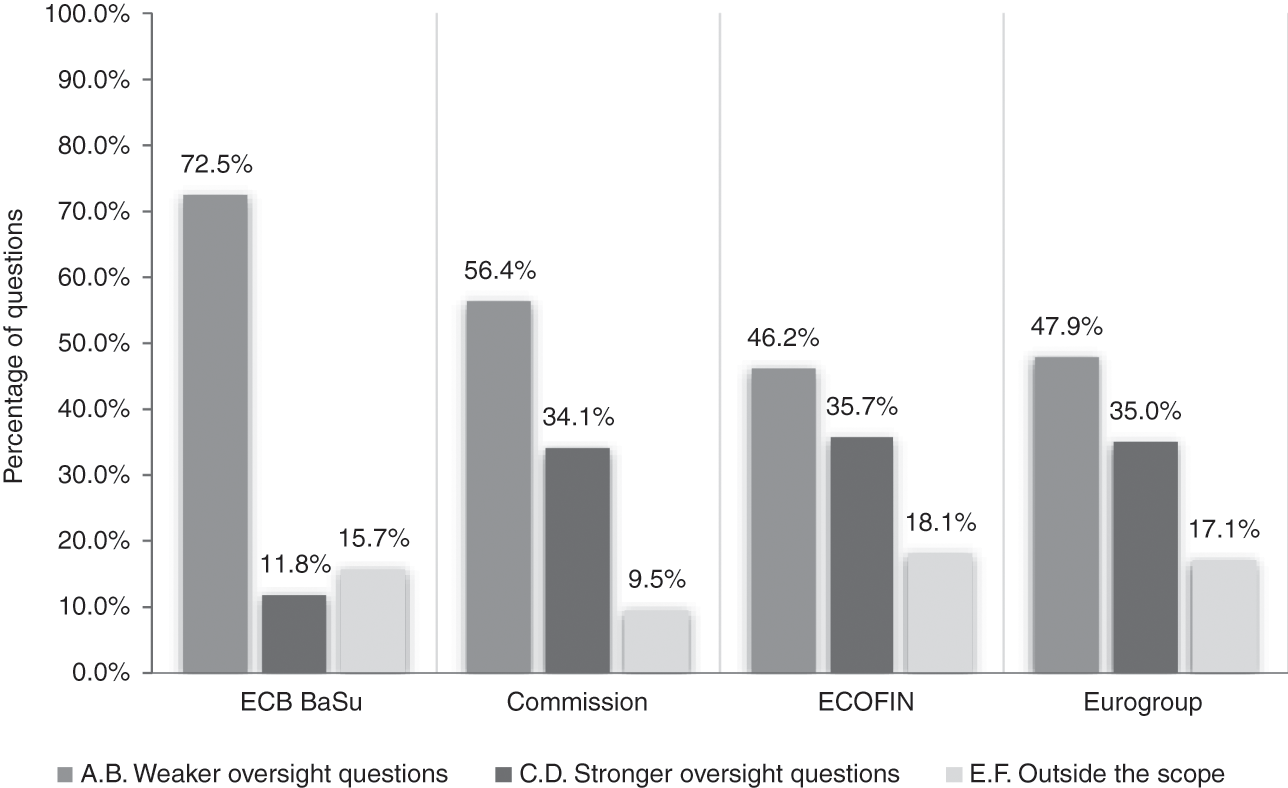

Next, there is also variation in relation to the types of questions asked by MEPs of the four institutions. In line with the analytical framework (Chapter 3.3), a distinction is made between weaker oversight questions (types A and B), stronger oversight questions (types C and D), and questions outside the scope of oversight (types E and F, where applicable). As stated at the outset, weaker oversight questions request information and justification of decisions by executive actors. Stronger oversight questions demand changes of decisions or conduct, and in more extreme cases, the imposition of sanctions on actors considered responsible for past errors. Stronger oversight questions are relevant for the responsiveness of executive actors to accountability forums and overlap with notions of control in principal–agent theory (Reference Fearon, Przeworski, Stokes and ManinFearon 1999; Reference StrømStrøm 2000). Finally, questions outside the scope of oversight simply ask for policy views from executive actors or mention irrelevant issues that have nothing to do with oversight or the policy area under discussion.

Figure 7.2 offers a snapshot of the typology of questions identified in the four cases covered in the book. While weaker oversight questions are the most frequent category employed by MEPs for all institutions, there is significant variation between the ECB in banking supervision (which received weaker oversight questions over 70 per cent of the time) and the ECOFIN Council or the Eurogroup (which received weaker oversight questions less than 50 per cent of the time). This finding is related to the institutional independence of the ECB in the EU political system and, subsequently, the sensitive nature of asking the ECB to change supervisory policy or conduct (see Chapter 4.1). The Commission is not far behind intergovernmental bodies, receiving weaker oversight questions 56 per cent of the time. Keeping in mind that the Eurogroup, ECOFIN, and the Commission are political bodies with key responsibilities in setting or implementing the policy agenda in economic governance, it would have been expected to find more examples of ‘stronger oversight questions’. Yet it is worth noting that within the category of ‘weaker oversight questions’, the number of requests for justification of conduct is higher than the number of requests for information (at least for the Commission and the Eurogroup, see Chapters 5 and 6). The only exception is the ECOFIN Council, which receives numerous demands for information as well as many questions for policy views (type E, outside the scope).

Figure 7.2 Types of questions posed by MEPs to each institution, based on Chapters 4–6

When it comes to ECOFIN and the Eurogroup, Figure 7.2 illustrates a similar division between types of questions; however, the topics discussed vary significantly. According to the book’s analytical framework (Chapter 3.3), accountability has an important ex post dimension of executive decisions. Yet in the Economic Dialogues with ECOFIN, MEPs focus on legislative dossiers in the ordinary or special legislative procedure and thus examine the activity of the Council as a legislative rather than as an executive body. In this respect, Dialogues with ECOFIN are better described as a form of ex ante policy-making by the EP as opposed to ex post oversight of executive decisions and conduct (Reference BovensBovens 2007a: 453). By comparison, the Economic Dialogues with the Eurogroup focus on financial assistance programmes and the role of Eurozone finance ministers on the ESM’s Board of Governors. It means that MEPs emphasise ex post oversight of executive decisions in the field. This is not to say that MEPs do not address questions for policy views to the Eurogroup, as these are present in 17.1 per cent of the identified instances. The difference is that such questions inquire about prospective Eurozone reforms, whose contours are typically set by the Eurogroup (and the European Council) before moving to the Commission and the Council in the formal decision-making process. While the questions still illustrate a form of ex ante policy-making, they are related to the role of the Eurogroup as the key executive actor in the EMU.

Overall, the performance of the EP as an accountability forum depends more on the activity than on the type of executive actor under scrutiny. Somewhat surprisingly, there is no significant difference between EP oversight of supranational institutions (the ECB and the Commission) and oversight of intergovernmental bodies (ECOFIN and the Eurogroup). The Eurogroup and the ECB are subject to more intense oversight by MEPs (as shown by the number of follow-up questions), but the direction of the scrutiny differs: MEPs often request the Eurogroup to change policies but do not (and cannot) ask the same of the independent ECB. Conversely, EP oversight of the Commission lacks focus, potentially because the Commission’s competences in the European Semester cover a variety of socio-economic issues that attract different attention in the Member States. Finally, the ECOFIN Council seems reduced to a legislative body from the perspective of EP oversight, which is unexpected because the Council machinery is still responsible for many executive decisions on the European Semester.

Keeping this in mind, the next section moves to comparing the types of answers provided by executive actors in response to EP oversight in the EMU.

7.1.2 The Responsiveness of EMU Executive Actors to EP Oversight

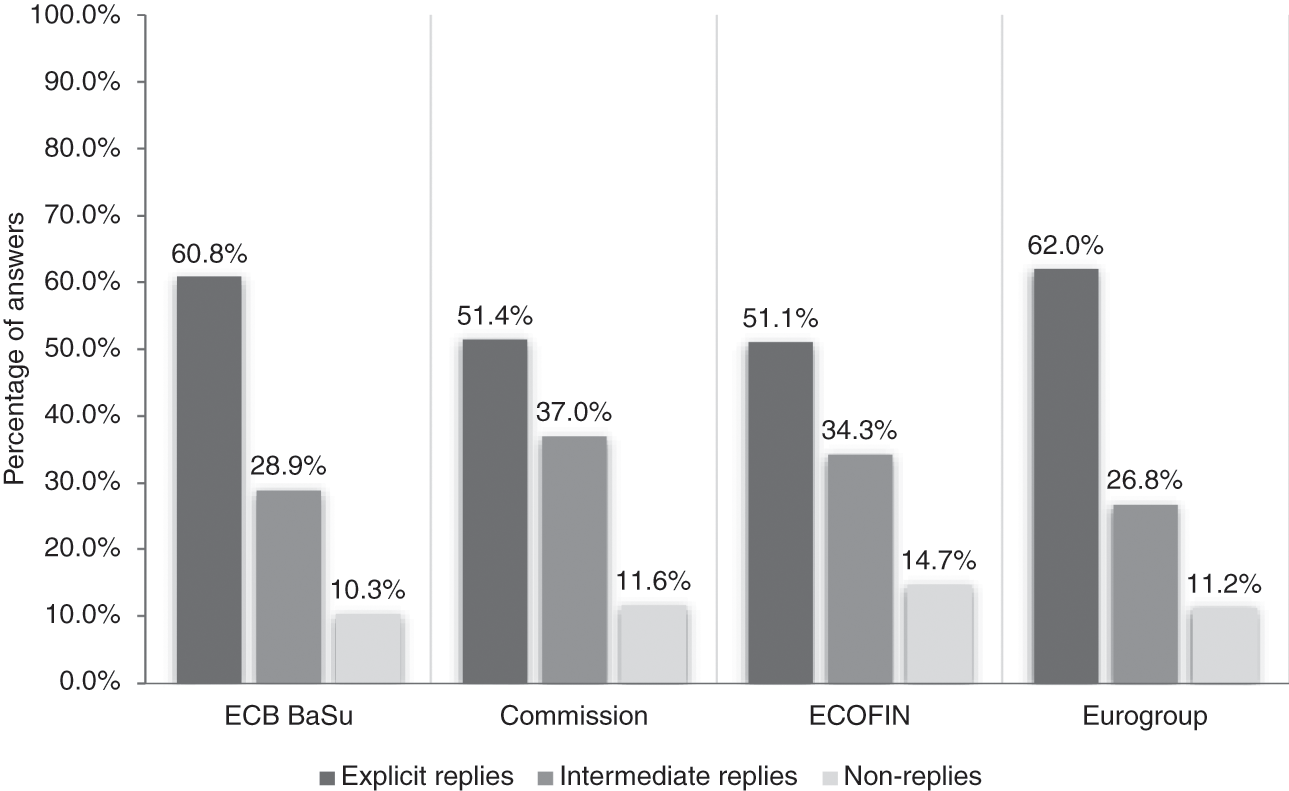

Figure 7.3 captures the classification between explicit, intermediate, and non-replies identified for the four institutions under consideration. A first observation stemming from the figure is that all institutions tend to provide more explicit replies than intermediate and non-replies combined. This is an important finding, confirming that EMU executive actors do not systematically seek to evade questions or give partial answers in response to the questions raised by MEPs. On the contrary, there is a tendency to engage with parliamentary questions head-on, especially on the part of Eurogroup President Jeroen Dijsselbloem and the Chair of the ECB Supervisory Board, Danièle Nouy. In respect of the Commission, there are some differences between ECOFIN Commissioners and the Vice-President for the Euro (who have similar levels of responsiveness) and EMPL Commissioners (with Marianne Thyssen having a better record than László Andor).

Figure 7.3 Percentage of explicit, intermediate, and non-replies provided by each institution, based on Chapters 4–6

Moving to the categories of intermediate replies, Figure 7.3 shows that the Commission and the ECOFIN Council have a higher tendency to give partial answers than the Eurogroup and the ECB on banking supervision. On the one hand, this might be due to the composite nature of questions put to the Commission and ECOFIN, as MEPs inquire about multiple dimensions regarding social or economic issues in the European Semester (for the Commission) or different points of ongoing legislative files (for the ECOFIN Council). On the other hand, some respondents simply do not engage with the substance of questions asked. In the case of the Commission, László Andor had the tendency to make generic statements that did not clearly address any of the questions raised, while in respect of ECOFIN, there were some Presidencies with a higher percentage of evasions or partial answers (e.g. finance ministers from Romania, Latvia, or Estonia). In fact, ECOFIN Presidencies also scored the highest number of non-replies (14.7%), although the difference is not as large when compared to the Commission (11.6%) and the Eurogroup (11.2%). In respect of non-replies, the ECB is a special case because its answers are often not about attempts at evasion but references to the secrecy regime in banking supervision and the institution’s lack of competence on the issues discussed by MEPs. In fact, out of the four institutions, the ECB has the most reasonable and legally defensible justification as to why it sometimes provides non-replies to parliamentary questions (10.3% of all instances).

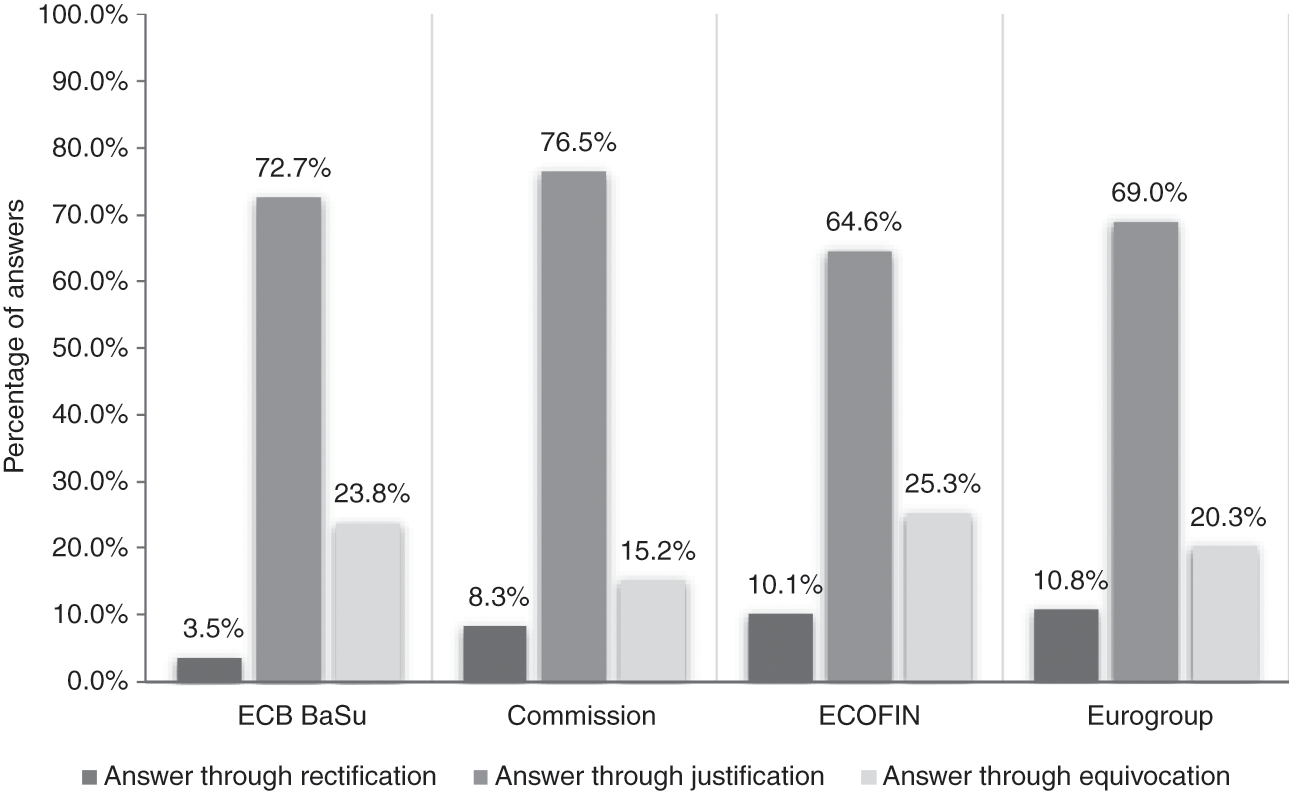

Furthermore, the analytical framework (Chapter 3.3) additionally made the distinction between answers that provide rectification (a promise to change conduct or correct past errors), answers that provide justification (defending conduct or explaining the rationale/content of a decision), and answers that try to equivocate (‘dodging a question’ or rejecting to comment because of confidentiality requirements or lack of competence on the matter). As shown in Figure 7.4, there is a general trend across the four institutions to answer questions through justification: this applies to over 70% of all replies from the Commission and the ECB on banking supervision, followed by the Eurogroup (69.0%), and the ECOFIN Council (64.6%). In other words, most parliamentary questions get answers providing information about existing/past/future policies, the rationale for past conduct, or explanations why a decision taken was the correct one. The last category is especially prevalent in answers given by the Eurogroup, the Commission, and ECOFIN in response to requests for policy change. This is a notable distinction because it suggests that EMU executive actors rarely commit to changing their decisions or conduct as a result of EP oversight. The ECB case is different because the majority of questions identified are ‘weak’ (types A and B), so the institution can only answer through the provision of information and justification of conduct.

Figure 7.4 Types of answers provided by each institution, based on Chapters 4–6

The low number of questions answered through ‘rectification’ reveals the limited responsiveness of the four institutions to the EP. In principal–agent terms, this means that parliamentary questions ensure little to no control of executive actors in the EMU. Due to its political independence, the ECB’s record is the poorest: MEPs cannot just ask the ECB to change supervisory policy in the SSM. In the few instances when rectification occurs, it is related to potential abuses of power by the ECB (a legal matter) as opposed to the direction of policy (a political matter). This logic does not apply to the other three institutions, which have political leadership and should in theory be responsive to the EP as a democratic accountability forum. Nevertheless, the analysis discovered a very low number of instances categorised as rectification, ranging from 8.3% to 10.8% of the replies identified for the three institutions.

In respect of equivocated replies, the Commission is doing better than the Eurogroup, the ECB, and the ECOFIN Council – which provide evasions or non-replies in more than 20 per cent of all instances. Again, the ECB is a special case because of the secrecy requirements in banking supervision, allowing the institution not to answer questions by invoking confidentiality rules. The Eurogroup and the ECOFIN Council do not have the same legal defence regarding the secrecy of their decisions. In fact, most of their equivocated answers are either examples of ‘dodging questions’ in Economic Dialogues or openly refusing to make public the positions of specific Member States in intergovernmental negotiations. For instance, in 2013, after the tumultuous negotiations of the financial assistance programme for Cyprus, Eurogroup President Jeroen Dijsselbloem repeatedly rejected questions on the internal dynamics of Eurogroup negotiations, arguing that the Council takes decisions as a whole and there is no reason to make country positions public (see Chapter 6.4.3). In the literature on Council and Eurogroup decision-making, consensus is a strong institutional norm protected by Council Presidencies and the Eurogroup President (Reference PuetterPuetter 2006, Reference Puetter2014). From this perspective, it is essential for the Council to present a unified front to the ‘outside’ world – including vis-à-vis the EP.

To sum up, there are many similarities regarding the responsiveness of executive actors to EP oversight in the EMU. All actors tend to provide explicit replies and answers justifying their conduct – offering information about past decisions, decision-making processes, or the rationale behind executive action. However, there are also clear differences between oversight interactions: the ECB and the Eurogroup provide fewer intermediate replies than the Commission and the ECOFIN Council, yet the Commission has the lowest number of equivocated answers. Moreover, there were only a handful of instances when executive bodies promised to rectify past policies or change decisions in response to demands made by MEPs. Yet although the percentage of answers through rectification remains low across the four institutions, the Eurogroup is outperforming the others – a surprising finding given its reputation for lacking accountability in the EMU (Reference Braun and HübnerBraun and Hübner 2019; Reference CraigCraig 2017). The next section discusses the comparative findings in light of the theoretical expectations of the book.

7.1.3 Assessing Oversight Interactions: A Comparison

In respect of the six scenarios of oversight interactions outlined in Chapter 3.3.1, it is possible to plot the four cases studies in the book on a continuum from ‘High control’ to ‘No control’ by the EP. When deciding the hierarchy among cases, the relative effect of the variables listed in Table 3.2 was considered in a qualitative fashion.Footnote 28 Most significantly, the analysis showed that MEPs asked stronger oversight questions when there was public pressure on an issue, as was the case of financial assistance programmes agreed by the Eurogroup or FOLTF decisions taken by the ECB in banking supervision. The more the media reported on an issue, the higher the likelihood for follow-up questions and stronger oversight requests by MEPs. Moreover, the influence of high public pressure was often related to ‘scandals’ reported by the media rather than the persistent discontent of citizens on sensitive topics such as the impact of austerity in countries affected by the euro crisis. Moreover, public attention to an EMU issue can offset the effect of other variables that would otherwise impact the performance of the EP as an accountability forum, such as its profile as a law-making parliament and its multi-party, multi-national composition. The interest of the EP in legislative dossiers was most significant in oversight interactions with the ECOFIN Council (given the relationship between the two institutions as co-legislators) and in the accountability hearings with the ECB on banking supervision (when MEPs would take advantage of the presence of the Chair of the Supervisory Board in the ECON Committee to ask for the ECB’s expert opinion on upcoming files). Conversely, the EP poses fewer questions to the Commission on legislative dossiers, although technically the Commission has exclusive right of initiative in the EU law-making process. Furthermore, under conditions of low public pressure – for example, in many Economic Dialogues with the Commission and the ECOFIN Council – parliamentary questions are diverse and diffuse, with few follow-ups, illustrating the diversity of political and national interests in the EP.

Next to public pressure, structural opportunities for oversight also had an important positive effect on the EP’s accountability relationships with executive actors in the EMU. The effect was evident in the format of committee meetings: whenever committee meetings were combined and more speakers were allowed in one round of Q&A, the number of intermediate replies and non-replies increased proportionately. For instance, joint Economic Dialogues with the Commission had so many speakers that it was difficult, if not impossible, for Commissioners to answer all the questions posed within the allocated time. Conversely, committee meetings with only one executive actor present allowed MEPs to get answers to their questions right away, for example, hearings with the Chair of the Supervisory Board or Dialogues with the Eurogroup President. The other issue related to structural opportunities for oversight concerns the adequacy of staff supporting MEPs to ask relevant questions of executive actors, which would could theoretically close the gap of asymmetric information usually found in executive–legislative relations (see Chapter 3.3.1). In this respect, most questions ‘outside the scope’ or ‘irrelevant’ requests were identified in accountability interactions with the ECB and the Commission, which carry out complex tasks in the EMU and benefit from a high level of expertise in comparison to MEPs (and their assistants). Under the circumstances, structural opportunities for oversight are limited because at times the EP lacks an understanding of the division of competences and the responsibilities of different institutions in the EMU.

In fact, the variable of asymmetric information between the EP and executive actors is most clearly present in the oversight interactions with the ECB in banking supervision. This confirms the expectation regarding the relationship between legislatures and bureaucracies/independent agencies (Table 3.2): indeed, the ECB is the least political of the four institutions covered in the book. As an expert body delegated to perform specific functions (banking supervision in the Eurozone), the ECB has much more information than MEPs regarding the operation of the SSM. Moreover, the ECB benefits from the professional secrecy requirements in banking supervision, which permit the Chair of the Supervisory Board not to disclose details about the individual banks supervised by the ECB. For this reason, the majority of questions addressed to the ECB are weaker, requesting information or justification of conduct. The dynamic of asymmetric information is less pronounced vis-à-vis the Commission, which is simultaneously an expert institution and a political body whose leadership was elected by the EP, according to Articles 14(1) and 17(7) TEU. In respect of ECOFIN and the Eurogroup, the aspect of asymmetric information goes hand in hand with the difficulties of disentangling collective decision-making in intergovernmental negotiations, as finance ministers are unlikely to share with the EP the details of country positions and compromises reached inside the Council.

At the same time, given the ex post definition of oversight used throughout the book, it was crucial to consider the focus of parliamentary questions, namely whether MEPs were interested in the ex post scrutiny of executive actors or if they were attempting to influence future decisions (ex ante policy-making). Regular definitions of accountability emphasise the ex post dimension, that is, accountability for past decisions and conduct (Reference BovensBovens 2007a: 453). Figure 7.5 shows the variation between the Eurogroup (placed in scenario 2, ‘Answerability’) and the ECOFIN Council (placed mid-way between scenario 4, ‘Transparency’, and scenario 6, ‘No control’). Not only does the ECOFIN Council have the highest number of non-reply, but also the issues covered in Economic Dialogues with ECOFIN revolve around the legislative process instead of the activities of the Council as an executive body. The ECON Committee used to meet with Council Presidencies before the introduction of the European Semester in 2010, so the euro crisis failed to change the dynamic between the two institutions – which interact as co-legislators rather than as parliaments and executives in legislative oversight. For this reason, the ECOFIN Council is placed on the lower end of the continuum from ‘High control’ to ‘No control’ by the EP in the EMU.

Figure 7.5 Overview of case studies in the book on the continuum from ‘high control’ to ‘no control’ by the EP in the EMU

The ex ante emphasis of EP scrutiny of the ECOFIN Council is also the reason why the case is classified below that of the Commission. Although the Commission gives a similar number of intermediate and non-replies as the ECOFIN Council (Figure 7.3), the supranational institution receives questions that are much more relevant for accountability than ECOFIN. Considering the topic of parliamentary questions, it is evident that MEPs use this type of oversight to scrutinise, ex post facto, decisions taken by the Commission on various instruments of the European Semester – their arbitrariness, effectiveness, or benefit for Member States in economic and social terms. By contrast, MEPs use the Economic Dialogues with ECOFIN to get their points across on legislative dossiers, demand information about the status of legislative negotiations in the Council, or ask the opinion of different Presidencies on the (desirable) outcome of a decision-making process. When MEPs press the ECOFIN Council on given issues, these are related to domestic developments in the country holding the Presidency (e.g. tax haven allegations against Cyprus, the Netherlands, or Luxembourg, see Chapter 6.2.2). Last but not least, the Commission has a better record than ECOFIN on equivocated answers – 15.2% as opposed to 25.3% of all replies in the data set – which shows that one in four replies provided by Council Presidencies do not engage with the issues at stake.

Next, if we compare the Commission to the Eurogroup, there are three reasons why the latter is ranked higher than the former on the continuum from ‘High control’ to ‘No control’ by the EP. First, MEPs pose far more follow-up questions to the Eurogroup President than they do to the Commission (55.7% vs 15.9% of all questionsFootnote 29). This clearly shows a keen interest from the EP to press the Eurogroup on specific issues – in particular financial assistance programmes or Eurozone-specific decisions in the European Semester. Although the preponderance of weak and strong oversight questions is similar for the two executive actors, it does matter whether MEPs push to get answers on the same topic or if they move on with other subjects in line with their diverse national or political interests. Furthermore, even though most questions focus on past activities of the two institutions (ex post scrutiny), it is easier for the Commission to get away with partial or equivocated replies than it is for the Eurogroup President. One explanation for this is the format of joint Economic Dialogues with the Commission, where time constraints do not allow MEPs to follow up on issues of interest to their committee or political group. Yet differences in answerability between two institutions cannot be ignored, as the Eurogroup provides on average more explicit replies than the Commission (62.0% as opposed to 51.4% of all replies). In fact, this is the second reason why the intergovernmental body was placed higher than the Commission in scenario 2 of oversight interactions – namely ‘Answerability’. The finding, however, might be related to the personal style of Jeroen Dijsselbloem, who was Eurogroup President for most of the period under investigation. By contrast, Mário Centeno displayed a lower responsiveness to parliamentary questions.Footnote 30

The third reason why the Commission is considered to have a worse record than the Eurogroup is related to democratic expectations in the EU political system. Legally speaking, the Commission is accountable to the EP (Article 234 TFEU), while finance ministers in the Eurogroup remain accountable to their respective national parliaments and citizens (Article 10 TEU). Accordingly, we would have expected the EP to exercise the strongest control over the Commission and, in turn, the Commission to be the most responsive executive actor in the EMU. Overall, the Commission is less prone to equivocation than the Eurogroup (15.2% vs 20.3% of all replies), but the Eurogroup acknowledges errors and promises rectification more often than the Commission (10.8% as opposed to 8.3% of all replies). For example, the Commission tends to justify its decisions on EDP sanctions or the MIP by claiming to apply the existing framework of rules in EU economic governance. But as demonstrated by the lax approach to sanctions or the arbitrary definitions of macroeconomic imbalances (Reference Dawson and MendesDawson 2019), the framework of rules in the EMU is more open to political interpretation than the Commission is ready to acknowledge. Conversely, the Eurogroup President repeatedly took responsibility for collective decisions taken by finance ministers, for instance, regarding the controversial financial assistance programmes for Cyprus in 2013 and Greece in 2015 (see Chapter 6.4). The problem is that the Eurogroup explains its decisions and defends them before MEPs, but there is nothing the EP can actually do to change the policies or course set by Eurozone finance ministers. For this reason, we can talk about ‘Answerability’ when it comes to EP oversight of the Eurogroup but certainly not about EP ‘control’ over the institution.

Finally, EP scrutiny of the ECB in banking supervision is a clear-cut case of scenario 4, ‘Transparency’. Given the low number of strong oversight questions addressed to the Chair of the Supervisory Board, the case could not compete with the Eurogroup and the Commission – which receive numerous requests for policy change. However, the ECB does better than the ECOFIN Council on two dimensions. First, MEPs pose more follow-up questions to the ECB than to ECOFIN (53.1% vs 30.8% of all questions). As discussed earlier in the case of the Eurogroup, follow-up questions reveal cross-national and cross-political interests of MEPs in holding an institution accountable on specific issues. Second, the Chair of the Supervisory Board is more open to answering questions than finance ministers representing Council Presidencies (bearing in mind that 60.8% as opposed to 51.1% of all replies given by the ECB are explicit). Moreover, if the ECB provides non-replies, this typically happens because of confidentiality requirements or lack of competence rather than due to evasion – which is the case with ECOFIN Presidencies. The secrecy regime in banking supervision remains a caveat for the oversight interactions between the EP and the ECB, blemishing an otherwise ‘clean record’ of the supranational expert institution.

On the whole, the analysis of EP oversight of executive actors in the EMU yields both expected and surprising results. The expected findings concern the focus on transparency in the scrutiny of the ECB in banking supervision, taking into account the institution’s independence and the confidentiality requirements of the field. In addition, we could have also anticipated the poor oversight of the ECOFIN Council by the EP – given that the two institutions used to meet in the ECON Committee prior to the accountability reforms introduced during the euro crisis. Conversely, results are surprising when it comes to the Commission and the Eurogroup: on the one hand, EP oversight of the Eurogroup was much more intense and better targeted than that of the Commission; on the other hand, the Eurogroup was more open than the Commission to accepting political responsibility for EMU decisions (through defence of conduct and sometimes rectification). But even in the case of the Eurogroup, EP oversight stopped short of ‘control’ in principal–agent terms: in other words, MEPs could make the Eurogroup answerable but not responsive (meaning amenable) to the EP as an accountability forum.

Having established the main features of oversight interactions between the EP and executive actors in the EMU, the following pages turn towards avenues for reform – in line with the deficiencies identified.

7.2 Looking Forward: Policy Recommendations

What implications does the analysis above have for the future of the EP as an accountability forum in the EMU? This section outlines concrete policy recommendations applicable to MEPs and the executive actors covered in the book. Based on the theoretical framework introduced in Chapter 3.3, policy recommendations are connected to broader ‘accountability purposes’ applied to the empirical evaluation of oversight interactions. Starting with the EP, the focus should be on increasing opportunities for follow-up questions (through the format of meetings), improving the relevance and strength of questions, and encouraging higher responsiveness from actors. In order to act as an effective accountability forum, the EP needs to examine, ex post facto, decisions by executive actors – demanding justification of conduct, changes of policy, and sanctions when deemed appropriate. Table 7.1 captures the key policy recommendations coming out of the empirical analysis. All items are applicable to oral questions, whereas recommendations #3–5 are also valid for written questions.

Table 7.1 Policy recommendations addressed to the EP in order to improve its performance as an accountability forum

| Accountability purpose | Concrete recommendations |

|---|---|

| Increase opportunities for follow-up questions |

|

| Improve the relevance of questions |

|

| Improve the strength of questions |

|

| Encourage higher responsiveness from executive actors |

|

The first accountability purpose, namely ‘improving opportunities for follow-up questions’ by MEPs, is well known in the specialised literature. With some variation, recommendation #1 has been made in previous research on the EP’s performance as an accountability forum, especially in respect of the Monetary Dialogues (see recently Reference Claeys and Domínguez-JiménezClaeys and Domínguez-Jiménez 2020; Reference LastraLastra 2020; Reference WhelanWhelan 2020). In terms of the format of meetings, many critics agree that the EP needs to lower the number of speakers per session to allow more time for each question and ensure a back-and-forth between MEPs and executive actors. In Table 7.1, the novelty concerns the coordination between political groups (recommendation #2) in advance of accountability hearings or dialogues with executive actors. Keeping in mind that all political groups appoint coordinators for each committee (Rule 214 of the EP’s current Rules of Procedure), the idea is to use coordinators’ meetings to organise the questioning of executive actors along specific lines of inquiry. This would give more coherence to the meetings and allow MEPs to put pressure on single issues, depending on their interests at a given moment in time.

The next accountability goal in Table 7.1 refers to the need to ‘improve the relevance of questions’ addressed by MEPs in accountability interactions. In any parliament, it is not realistic to expect members to have expertise on all the issues pertinent to the activity of executive actors. The EMU is more complicated than a national system because of overlapping competences between different EU institutions and national authorities (as shown in Chapter 4.3 in relation to banking regulation, supervision, and resolution). For their part, parliamentary assistants may be overwhelmed by the amount of information available on the implementation of different EMU policies. As a result, it would be beneficial for MEPs to receive expert guidance on policy issues relevant for legislative oversight (recommendation #3). For example, research departments in the EP’s administration could provide MEPs with a list of potential questions relevant for each executive actor in a given month/quarter. In EMU sub-fields, questions can be compiled by research-oriented departments such as the EGOV or the economic branch of the DG for Internal Policies of the Union. While this might increase the workload of the departments, the solution would take advantage of existing in-house knowledge regarding institutional competences and policy problems in the EMU.

Next, there is the goal to ‘improve the strength of parliamentary questions’ by going beyond requests for information to demands for justification of conduct, changes of policy, or sanctions of actors. While such an increase would not apply equally to all institutions (e.g. the ECB), the point is to shift the focus from what EMU executive actors are doing to assessing the appropriateness – however defined – of a course of action. Such an evaluation would require MEPs to specialise in the activities of all executive actors, which is not feasible given the high number of executive institutions in the EMU (the Commission, the ECB, the Council, Eurogroup, SRB, etc.). For this reason, recommendation #4 proposes a division of labour within political groups, allowing different MEPs to take the lead in different oversight interactions. For example, permanent members of the ECON Committee could choose to focus on the ECB, the Commission, or the Eurogroup – facilitating a gradual specialisation in the mandate and instruments adopted by one institution. This was illustrated in the past in the accountability relationship between the EP and the ECB in banking supervision, when members like Pervenche Berès (France, S&D) or Sven Giegold (Germany, the Greens/EFA) clearly had the expertise to question supervisory decisions in a systematic manner (see Chapter 4.3) – which improved the quality and intensity of Q&A sessions.

Politically speaking, MEPs might reject such specialisation as undesirable because they would like to keep a ‘generalist profile’ in case they change committees or careers after their term comes to an end. Nevertheless, the move would make a lot of sense in the EP – given both the size of the assembly and the diversity of national interests (as well as the EU interest) it seeks to represent. The point is to facilitate a parliamentary focus on the ex post decisions taken by specific institutions and examine their appropriateness (recommendation #5). A similar notion is advocated in policy research by those who argue that MEPs need to ask more ‘technical’ questions, in line with the mandate of each executive actor (e.g. Reference Claeys and Domínguez-JiménezClaeys and Domínguez-Jiménez 2020; Reference LastraLastra 2020; Reference WhelanWhelan 2020). The ‘appropriateness’ of executive action can be judged in multiple ways – assessing for instance whether decisions have been transparent, non-arbitrary, effective, or advancing the public interest (Reference Dawson and Maricut-AkbikDawson and Maricut-Akbik 2020). In other words, the current allocation of MEPs into committees is not sufficient to achieve the goal of specialised oversight.

Finally, the EP could ‘encourage higher responsiveness from executive actors’ using the existing voting system to evaluate instantly answers to parliamentary questions (recommendation #6). This would offer MEPs the chance to signal on the spot whether they accept, reject, or are indifferent to replies given by executive actors in a committee meeting. The system would be imperfect because political groups on the fringes will always be inclined to evaluate the responsiveness of executive actors in a negative manner. Yet the more interesting finding will refer to the voting behaviour of MEPs from the main political groups, who also supported the Commission President and the College. For their part, executive actors will be more likely to answer questions explicitly, avoid generic answers, or refrain from dodging questions if they know their performance is evaluated immediately by MEPs present in committee meetings.

Moving to the responsiveness of executive actors, Table 7.2 provides both general and institution-specific recommendations. The first accountability goal mentioned refers to the imperative to reduce the number of non-replies or equivocated answers. These occur for different reasons, so two of the recommendations are general and two are tailored to the ECB and the Commission, respectively. In respect of oral questions, it is essential for all executive actors to stop making generic statements in order to pass the time allocated to an answer in committee meetings (recommendation #1). When MEPs ask questions that are outside the competence of an executive body, the responding actor should explain the division of competence and why their institution is not the appropriate addressee for that specific issue (recommendation #2). In banking supervision, the problem is the strict secrecy regime that does not allow the ECB to answer many questions on supervisory decisions on individual banks (see Chapter 4). A possible solution is to reform the system in a way that takes into account the concerns of supervised banks and responds to the public interest in knowing what the ECB actually does in the field. The idea proposed here is to establish a specific time period after which supervisory decisions can become public (recommendation #3). The waiting period will ensure that the positions of financial institutions are not jeopardised in the eyes of depositors or competitors – thus alleviating key concerns regarding transparency in banking supervision (Reference AngeloniAngeloni 2015). For the Commission, one problem identified in Chapter 5 was the format of joint committee meetings, which allowed several speakers to pose multiple questions to two to three Commissioners in one sitting. Accordingly, the proposed solution invites the Commission to collaborate with the EP in order to streamline the Q&A process in Economic Dialogues, ensuring that one question is put to one respondent at a time (recommendation #4).

Table 7.2 Policy recommendations addressed to EMU executive actors in order to improve their responsiveness to the EP

| Accountability purpose | Concrete recommendations |

|---|---|

| Reduce number of non-replies or equivocated answers | Applicable to all:

|

| Reduce number of intermediate replies |

|

| Increase number of answers through rectification |

|

The second accountability goal listed in Table 7.2 emphasises the need to ‘reduce the number of intermediate replies’. As found in Chapters 3–6, intermediate replies are often the result of multi-pronged questions, when MEPs inquire about several issues using one or two interrogative sentences. In response, executive actors tend to answer such questions only in part, making it difficult to assess whether the reason is obfuscation or lack of time to engage with all the aspects raised by an MEP. If the reason is obfuscation, it is essential for executive actors to engage with different parts of a question by providing clear and concise responses. When time does not allow for comprehensive replies, actors could promise MEPs to provide written answers after the meeting – and then task their administrative staff to do so (recommendation #5).

Last but not least, there is the sensitive issue of ‘answering more questions through rectification’ – by promising to change policies or conduct in the future (recommendation #6). This is particularly applicable to executive bodies with political leadership: the Eurogroup, the ECOFIN Council, and the Commission. Being responsive to EP oversight would mean that systematic demands for policy change by MEPs are taken into account by executive actors. This is not to say that executive bodies should make endless promises to implement changes in response to every request made by an MEP. Nevertheless, when several political groups draw attention to specific decisions or conduct, executive actors should show openness and consideration of the merits of the claims.

Overall, the feasibility of the recommendations above depends on the political will of MEPs and the leadership of executive actors in the future. The following years will be crucial to establish a functional oversight relationship between the EP and EMU executive actors. The EU response to the COVID-19 crisis will have long-term implications on the economic governance framework given the adoption of the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) – expected to last until 2027. The RRF is a financial support instrument of up to €672.5 billion that will be allocated to Member States in the form of grants and loans designed to help alleviate some of the negative economic effects of the pandemic (European Commission 2021). The RRF is revolutionary in many ways, allowing the accumulation of EU debt for the purposes of common expenditure and creating EU fiscal capacity for the first time, albeit as a temporary measure (Reference Guttenberg, Hemker and TordoirGuttenberg et al. 2021).

In terms of institutional changes, the RRF will be merged with the European Semester for the 2021 cycle, with governments being asked to replace the submission of annual reform programmes with national recovery and resilience plans, listing the investments for which they require EU funding (European Commission 2020a). The Commission will be in charge of evaluating the plans (similar to the Semester process), while the Council will give final approval on a case-by-case basis (European Commission 2021). This means that both the Commission and the ECOFIN Council (rather than the Eurogroup) will have a prominent role in the RRF and be subject to public scrutiny. In this context, MEPs have a chance to affirm their role as an accountability forum by keeping a close eye on decision-making and ensuring that executive actors stick to the promises made in order to obtain EP support, for example, the focus on green transition, digital transformation, or respect for the rule of law (European Parliament Press Release 2021). From the perspective of democratic accountability, the EP should seize the opportunity to oversee this new yet significant increase of executive power in EU economic and fiscal policies.

Beyond the EMU, the analysis in the book raises important questions about the role of the EP in improving the EU’s democratic accountability credentials. The final section problematises the discussion.

7.3 The Big Picture: EP Oversight and EU Accountability

To put the analysis of the book into perspective, the final question addressed is whether effective oversight by the EP will solve the EU’s long-standing accountability deficit – in the EMU and beyond. As described in Chapter 3.1, accountability is a multi-faceted concept that carries political, legal, and administrative connotations (Reference BovensBovens 2007a; Reference Dubnick, Bovens, Goodin and SchillemansDubnick 2014). EP oversight of executive actors is a form of political accountability that cannot replace judicial review of EU decisions by national and EU courts, auditing by the ECA, or administrative review by the European Ombudsman. These mechanisms need to function simultaneously: a strong process of judicial review will not make up for weak political accountability mechanisms – or the other way around (Reference Dawson, Maricut-Akbik and BobićDawson et al. 2019). Even in the realm of political accountability, improving the EP’s performance in legislative oversight will not fix, on its own, the EU’s long-standing democratic accountability problems. The issues are systemic, rooted in the complexity of a multi-level, multi-national polity (Reference Brandsma, Heidbreder and MastenbroekBrandsma et al. 2016: 624–625) in which democratic elections take place regularly but where political competition does not translate into control of the policy agenda (Reference Føllesdal and HixFøllesdal and Hix 2006). Improving the effectiveness of EP oversight of executive actors is therefore a necessary but insufficient condition to overcome the EU’s systemic accountability problems. However, such reforms can help expand political accountability at the supranational level and improve perceptions of democratic legitimacy among citizens. The argument is developed below.

The starting point is the complexity of the EU political system, which makes it difficult to identify the ‘right actors’ accountable for past decisions (Reference BrandsmaBrandsma 2013: 50–51). First, EU decisions are taken collectively, so it is impossible to disentangle individual responsibility at the national level – which means that citizens cannot easily assign blame via the ballot box (Reference Hobolt and TilleyHobolt und Tilley 2014). Second, EU decision-making involves numerous networks of national and sub-national authorities that lead to a dilution of responsibility and a higher likelihood of blame-shifting from one level of governance to the other (Reference BovensBovens 2007b; Reference Harlow and RawlingsHarlow and Rawlings 2007; Reference PapadopoulosPapadopoulos 2010). Third, from a principal–agent perspective, EU executive actors can have multiple principals with conflicting objectives, for example, national electorates, EU citizens, national governments, the EP, and so on, which inflate and confuse the object of accountability (Reference BusuiocBusuioc 2013; Reference DehousseDehousse 2008). To put it bluntly, the EU political system makes it difficult to know who is responsible for what or why that is the case.

Furthermore, democratic elections take place on a regular basis but offer citizens few opportunities to hold EU actors accountable in practice (Reference Gustavsson, Karlsson, Persson, Gustavsson, Karlsson and PerssonGustavsson et al. 2009). As mentioned above, national elections are undermined by collective decision-making at the EU level, whereas EP elections remain disconnected from EU politics or considerations of control over the policy agenda. In respect of the EP, the lack of an ‘electoral connection’ between MEPs and their voters is notorious (Reference Hix and HøylandHix and Høyland 2013: 184). EU citizens do not vote in EP elections in response to the performance of individual MEPs or their political groups; instead, voters often cast ballots in order to ‘punish’ national governments for domestic issues (Reference Hix and MarshHix and Marsh 2007). Moreover, even if citizens had clear preferences about the direction of EU policies, EP political groups would not be able to translate them into policy outputs in the same way as national parties (Reference Lindberg, Rasmussen and WarntjenLindberg et al. 2008; Reference MühlböckMühlböck 2012). Given the complexity of the EU decision-making process, the EP has to negotiate constantly and reach compromises with the other institutions (Reference Hix and HøylandHix and Høyland 2011: 131–133). The dynamic illustrates the problem described above, namely the difficulties of identifying the ‘right actors’ responsible for EU decisions and subsequently holding them accountable.

Taking all this into consideration, it becomes clear that EP oversight of executive actors is only one element of political accountability in the EU. Improving its effectiveness will not magically solve the EU’s infamous democratic deficit (Reference Føllesdal and HixFøllesdal and Hix 2006). Yet there is significant added value in enhancing EP scrutiny of EU executive actors in the EMU and beyond. To begin with, parliamentary oversight offers a way to bridge the gap between those who hold authority in the EU political system (the citizens) and those who exercise it on their behalf (EU executive institutions) (cf. Reference Føllesdal and HixFøllesdal and Hix 2006). Indeed, MEPs can ask questions of EU executive actors drawing on items of concern in their own constituency – which is one of the basic purposes of parliamentary questions (Reference MartinMartin 2011a; Reference Wiberg, Koura and WibergWiberg and Koura 1994). Next, effective oversight can improve citizen perceptions of democratic legitimacy in the EU and increase their attentiveness to the EP as a representative assembly. For instance, if citizens see footage of confrontations between MEPs and EU executive actors in committee meetings or if they read media reports of effective parliamentary questioning, they are likely to appreciate the activity of their representatives in holding executive actors accountable.

At the same time, effective oversight can increase the informal influence of the EP in the EU political system. Heated committee hearings or pointed written questions are likely to attract media attention and put public pressure on EU executive actors to change conduct or adjust policy decisions. The EP has thus a lot to gain from expanding its profile as an accountability forum, keeping in mind that ex post scrutiny has pre-emptive effects on the behaviour of actors – who know they will be constantly observed and questioned about their decisions (Reference SchillemansSchillemans 2016: 1408). To put it differently, after fighting for decades to expand its budgetary and legislative competences, the time has come for the EP to assert its scrutiny powers – which it already possesses in many policy fields. In this respect, the EMU provides an excellent setting for the EP to exercise its oversight powers and hold EU executive actors accountable in an area at the heart of citizens’ concerns.