Perhaps the most underappreciated dimension in public response to the post-Bush v. Gore controversies involving state election administration and Supreme Court jurisprudence involving the right to vote has been the central role of Congress in enforcing the Fifteenth Amendment.

As a scholar of American electoral politics, legislative representation, and black political engagement, I sought placement with the House Committee on the Judiciary of the 113th Congress [hereafter the Judiciary Committee] to learn more about the history of congressional efforts to nationalize election standards and to protect voting rights. I was especially interested in examining how members of Congress thought about the recent spate of judicial rulings affecting federal election law and how members imagined the future of congressional action to address racial and socioeconomic disparities in participation and representation. Moreover, I relished the opportunity to work for Michigan Rep. John Conyers (Thirteenth District). Conyers is a founding member and the “Dean” of the Congressional Black Caucus, the first African American chair of and then-ranking member of the Judiciary Committee, the second most senior member of the House, and is a member of the original enacting coalition of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965. Conyers was also present at the White House for the founding of the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization dedicated to combating discrimination against racial and ethnic minorities formed in 1963 at the behest of President John F. Kennedy. During his four-decades plus in Congress, Conyers has spearheaded a wide range of legislation, including the National Voter Registration Act of 1993, the Martin Luther King Holiday Act of 1983, the Violence Against Women Act (of 1993 and of 2013), and the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) of 2002. Members frequently turn to Conyers for his insight into the workings of Congress and for his leadership across a range of issues (Grose Reference Grose2011; Rivers Reference Rivers2012).

Established as a standing committee of the House in June 1813, the Judiciary Committee has substantial policy and oversight jurisdiction over issues and agencies affecting constitutional protections. The committee's jurisdiction includes administrative practice, bankruptcy, espionage, terrorism, constitutional amendments, civil rights and liberties, criminal law enforcement, federal courts and judges, interstate compacts, immigration and naturalization policy, impeachment, claims against the United States, codification of statutes, subversive activities affecting the internal security of the United States, and federal apportionment. The committee's oversight of the Department of Justice and the Department of Homeland Security enables members to affect the protection of civil rights and civil liberties at all levels of government. The 40-member Judiciary Committee (with 23 Republicans and 17 Democrats) reflects a diverse array of recently elected and long serving members, with the latter group containing current or former committee chairs/sub-committee chairs of the Judiciary Committee and of other House committees. My staff appointment with the Judiciary Committee provided me with an ideal vantage point from which to examine the processes affecting federal response to public angst about reforms in election law, especially to the concerns expressed by communities of color about the racially disproportionate impact of certain election reforms.

The public clamor for president-centered leadership in protecting election integrity is understandable, but its long history is not without potential consequence for Congress (Nelson Reference Nelson2008). President Obama drew praise for his 2010 State of the Union Address remarks criticizing the Court's decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission which upended congressional law (and prior judicial deference to the legislative branch's expertise) governing the public financing law. Obama also earned applause for his 2012 reelection night victory speech remarks about the problem of lengthy wait times at the polls—he stated “we have to fix that”—and for issuing Executive Order 13639 that created the Presidential Commission on Election Administration. In June 2013, Obama drew similar praise for remarks reassuring Americans that the Department of Justice would continue to vigorously defend voting rights following the Supreme Court's decision in Shelby County v. Holder invalidating the Voting Rights Act's coverage formula determining the jurisdictions that were automatically required to submit proposed changes in election procedures for federal preclearance. Yet, sidelined in much of the public's exalting of executive leadership is the difficult nature of establishing national baseline standards governing elections. The challenge of negotiating such standards was not diminished by debates over the butterfly-ballot design and illegal voter purges in Florida during the 2000 election cycle, the Bush v. Gore decision, or over the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002. Nor did passage HAVA diminish this challenge; in fact, it may have intensified the challenge. Whereas proponents of HAVA characterized the law as addressing enforcement gaps learned from implementation of the Voting Rights Act and the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA or “Motor Voter), opponents countered that the three laws undermined state ballot security/antifraud measures governing provisional balloting, voter registration, voter identification, and voting systems. Weak enforcement of Help America Vote Act and challenges to its constitutionality raised concerns that federal directives to adopt nondiscriminatory election procedures could be dead letters. Such concerns intensified after disclosure of voter caging in Ohio during the 2004 election cycle and before and after the 2006 Voting Rights Act reauthorization hearings. The debate further intensified following the Supreme Court's decisions in Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life, Inc. (2007), which carved out exceptions to the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act's limitations on political advertising, and after the Court's decision in Crawford v. Marion County Election Board (2008) upheld Indiana's photo voter-identification law. Some within Congress wondered aloud if the federal judiciary would continue to misconstrue congressional intent. For example, Democrats in Congress did not miss that the Court had rejected arguments in amicus briefs filed by some members that the Indiana law contravened Congress's “expressed intent” in the Help America Vote Act regarding the specific list of acceptable forms of identification. As outcries for action intensified, members of Congress, led by Rep. Conyers and others, continued to press Congress to reclaim its lead in efforts to protect the right to vote. These outcries were meant to focus public debate on congressional authority to protect the franchise from the reemergence of discriminatory election procedures. This power emanates from the Civil War Amendments, the Movement Amendments (i.e., the Nineteenth, Twenty-Fourth, and Twenty-Six Amendments), and from the Elections Clause [Article I, § 4, cl. 1] that enables Congress to prescribe regulations of the “Times, Places, and Manner of holding elections” (except as to the place of choosing senators).

My time with the Judiciary Committee enabled me to see first-hand the ferocity of public outcries for federal action, the ways in which public outcries often privilege executive action, and the growing instability in judicial precedents governing election law (Grose Reference Grose2011). As a committee staffer interested in election law and civil rights, I had the privilege of working directly with Minority Staff Counsels Keenan Keller and Michelle J. Millben, under the supervision of Minority Chief of Staff and Chief Counsel Perry Apelbaum, as well as working with staff and counsels from the offices of other members. These experienced attorneys and veterans of the Hill (many who have worked for both chambers and parties) provided me with insights from their decades of work with the Judiciary Committee and Rep. Conyers. My work portfolio included drafting and compiling materials for briefings, hearings, meetings, and press releases; researching case law for, and commenting on, drafts of amici briefs related to Shelby County v. Holder and Arizona v. the Inter-Tribal Council of Arizona (a challenge to the state's documentary proof-of-citizenship requirement as being preempted by NVRA's requirement for states to accept the common federal registration form); analyzing proposed congressional legislation in key areas; tracking media accounts and state actions involving select election laws; and compiling a record of Supreme Court decisions from 2005 that have affected congressional authority to protect constitutional rights. I accompanied Counsels Keller, Millben, and Apelbaum to meetings with Conyers and to Hill meetings with stakeholders, members of Congress, and other Hill staff. I assisted on projects addressing redistricting, early voting, public campaign finance, a national day for voter registration, the reintroduction of a bill banning racial profiling (e.g., the End Racial Profiling Act of 2013 (H.R. 2851), and the reintroduction of the Voter Empower Act of 2013 (H.R. 12)—an omnibus bill sponsored by Georgia Representative John Lewis which would, among other things, prohibit deceptive practices and which would modernize voter technology. I will forever cherish those walks with Conyers and with counsels. Those precious moments gave me invaluable information about the politics, processes, and personalities underlying congressional behavior and public perception of voting rights.

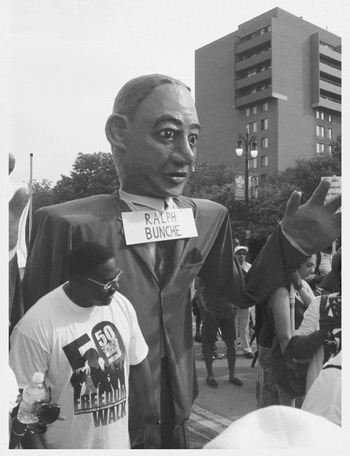

One of the more interesting moments of my fellowship was the trip to Michigan's Thirteenth Congressional District, which includes much of Detroit and portions of its suburbs. I accompanied District Director Yolanda Lipsey and Conyers to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Think Tank for Social Action (MLK Think Tank) conference associated with the 50th anniversary march commemorating the Walk to Freedom/Freedom Walk, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on June 23, 1963. It is at that famous march where Dr. King gave remarks that are widely regarded to be the original debut of his now famous “I Have a Dream” speech. The MLK Think Tank sessions were held at the famed United Auto Workers building in Detroit. Conyers gave remarks at the standing-room only “Labor and Church Working Together” session of the MLK Think Tank, took questions, and encouraged audience members to turn out in numbers for the march. They did. I joined Conyers, Lipsey, and thousands of other people in the one-mile or so walk from Woodward Avenue to Hart Plaza, where the walk ended with a rally and speeches from a wide range of fellow walkers, including Martin Luther King III, Rosalyn Brock, Jesse Jackson, and Al Sharpton. The Freedom Walkers with whom I chatted all expressed a strong connection to the moment and to the importance of learning from the past. Many Freedom Walkers saw similarities between today and past eras when sectionalism and political party interests trumped procedural and substantive protections for civil rights. The visual iconography was impressive. There were signs reminiscent of the 1963 March on Washington and puppets of my heroes, like Ralph Bunche, A. Phillip Randolph, and Martin Luther King, Jr. (see figure 1). Unfortunately, I did not see any puppets of my heroines from the Civil Rights Movement. As the immediate past president of the National Conference of Black Political Scientists and as a former Fulbright Scholar to Ghana, I was especially intrigued by the puppeteers' choice to use Bunche during the 2013 Freedom Walk. Among other things, Bunche was a native of Detroit, the first African American president of the American Political Science Association, a diplomat to the United Nations, a specialist in African affairs, a research collaborator with Gunnar Myrdal for work resulting in publication of An American Dilemma (1944), a Nobel Peace Prize winner, and one of the organizers of the 1963 March. Bunche challenged conventional thinking inside and outside of academia. One can also read Bunche's work as an endorsement or repudiation of representational identity politics, whether those identities are built around party, racial identity, religion, or region (Reed Reference Reed1999; Rehfeld Reference Rehfeld2005; Williams Reference Williams2008). If the 1963 March on Washington highlighted any one theme, it highlighted the price American democracy pays when identities determine the freedoms that all citizens enjoy.

Figure 1 Marchers chat during the 50th anniversary march commemorating the June 23, 1963 “Walk to Freedom” in Detroit, Michigan

Photo courtesy of Tyson King-Meadows

By the mid-point of my APSA fellowship, I began to gain a deeper appreciation for the three realities of contemporary representational politics that have made it harder for Congress to grapple with the various manifestations of blatantly illegal and constitutionally suspect election practices. First, the electorate's growing penchant for president-centered leadership and for embracing presidential and congressional candidates who hope to win office by running against Congress (Mann and Ornstein Reference Mann and Ornstein2006; Nelson Reference Nelson2008). Second, an oft-unspoken and highly incorrect assumption that “protecting voting rights” is principally about protecting the voting rights of racial, ethnic, and language-minorities (Minta Reference Minta2011; Rivers Reference Rivers2012). Third, the steady disappearance of “institutional partisans” in Congress (Mann and Ornstein Reference Mann and Ornstein2012), legislators who are loyal to and protective of the legislature's predominance in the constitutional order, and the raucous ascendency of party partisans (Mann and Ornstein Reference Mann and Ornstein2012). The latter groups has been accused of exploiting procedural mechanisms to strengthen the power of the majority party at the expense of the rank-and-file members and the minority party (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2005; Strahan Reference Strahan2007). My staff appointment with the Judiciary Committee afforded me an opportunity to walk among institutional and party partisans and to see firsthand why today's politics make it impossible for any members to be permanently and/or wholly wedded to either type of partisanship, especially in the areas of civil rights and civil liberties (Fenno Reference Fenno2003; Tate Reference Tate2010).

As of this writing, it remains unclear if, when, and how the institutional partisans inside and outside of Congress will prevail in efforts to strengthen the VRA in the wake of the Shelby County v. Holder ruling and to confront the repackaging of racially discriminatory election reforms. My experience on the Hill convinces me that only a bipartisan, Congress-centered, historically grounded, and multi-dimensional policy approach will work. Such an approach will give primacy to long-term national interests, over short-term sectional interests. It will also provide citizens with the best statutory protections against forces intent on using intergovernmental relations as blood sport and intent on seizing policy control as the spoils of electoral machinations.

The stakes for the country could not be higher if the Congress fails to reassert its constitutional predominance. Some Americans seem unconvinced that assaults on congressional authority are harbingers of future threats to egalitarianism. Nonetheless, it is difficult for institutional partisans of Congress not to draw parallels between today's era and earlier eras when the disregard for legislative intent undermined the rights of all Americans by jeopardizing the rights of some. The rhetorical and legal frameworks established to thwart congressional action protecting the civil rights of racial and ethnic minorities undergird current challenges to federal policies governing public health, the environment, housing, education, employment, foreign affairs, judicial transparency, and campaign finance. Now I better understand the Sisyphean task some representatives face when trying to persuade colleagues and constituents that (a properly constituted) Congress must be the center of gravity in American politics. Mass and elite anxiety toward institutional partisanship in Congress may help not only to explain America's post-nineteenth century fixation with executive governance, but may also help scholars understand the ways in which member and staff longevity affect the policy and discursive space representing the differences and tradeoffs between constituent preferences and constituent interests.