Book contents

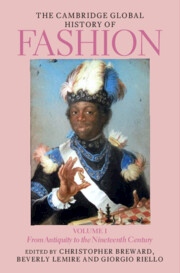

- The Cambridge Global History of Fashion

- The Cambridge Global History of Fashion

- The Cambridge Global History of Fashion

- Copyright page

- Contents for Volume I

- Figures for Volume I

- Maps for Volume I

- Table for Volume I

- Contributors for Volume I

- Preface

- 1 Global History in the History of Fashion

- Part I Multiple Origins of Fashion

- Part II Early Modern Global Entanglements

- 7 Magnificence at the Royal Courts in the Islamic World

- 8 Early Modern Fashion Cities

- 9 Fashioning Possibilities

- 10 Fashion Beyond Clothing

- 11 Fashion and the Maritime Empires

- 12 Garments of Servitude, Fabrics of Freedom

- Part III Many Worlds of Fashion

- Index

- References

11 - Fashion and the Maritime Empires

from Part II - Early Modern Global Entanglements

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 August 2023

- The Cambridge Global History of Fashion

- The Cambridge Global History of Fashion

- The Cambridge Global History of Fashion

- Copyright page

- Contents for Volume I

- Figures for Volume I

- Maps for Volume I

- Table for Volume I

- Contributors for Volume I

- Preface

- 1 Global History in the History of Fashion

- Part I Multiple Origins of Fashion

- Part II Early Modern Global Entanglements

- 7 Magnificence at the Royal Courts in the Islamic World

- 8 Early Modern Fashion Cities

- 9 Fashioning Possibilities

- 10 Fashion Beyond Clothing

- 11 Fashion and the Maritime Empires

- 12 Garments of Servitude, Fabrics of Freedom

- Part III Many Worlds of Fashion

- Index

- References

Summary

These are the opening lines of a popular French song that has its roots in the Caribbean islands that were colonized by France.2 It is written from the perspective of a Creole woman who is expressing her grief as she realizes that her lover – presumably a white French sailor – has left the island. In the song there is a deliberate deployment of textile artefacts (foulard and Madras) as symbols of the loss that the woman experiences. She is not only sorry that her lover is leaving, but also lamenting that she will no longer have access to fine things like textiles and gold jewellery (collier choux), which were fashionable in the eighteenth century in the French Caribbean.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge Global History of FashionFrom Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century, pp. 363 - 398Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2023