Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 September 2011

Summary

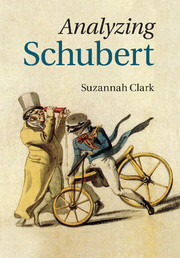

Not long ago, a previously unknown watercolor featuring Schubert was discovered (Plate 1). Dating from July 16, 1818, it depicts Schubert peering through a kaleidoscope and his friend Leopold Kupelwieser (also the painter of the caricature) riding a draisine. Both the kaleidoscope and draisine were newly invented objects at the time of the painting. The kaleidoscope originated in Scotland, invented as a scientific tool by Sir David Brewster, and around the time it fell into Schubert’s hands it was all the rage in Vienna as a toy. The draisine or “Laufmachine” was invented in Germany – a kind of Fred Flintstone precursor of the bicycle, without pedals, whose function was to transport crew and materials for railway maintenance. Around 1818, it had made its way off the railtracks and into the city for leisure riding. Schubert and Kupelwieser are both portrayed as absorbed by these new technologies: Kupelwieser is so fixated on the draisine that he crashes into Schubert, and Schubert is so enthralled by the kaleidoscope that he does not see him coming.

In its original context, the watercolor was accompanied by the following commentary:

The latest example of contemporary history proves just how dangerous the landslide of new developments is from Paris. But even the seemingly harmless inventions of the kaleidoscope and the draisine have their danger, as the accompanying picture illustrates. The stout gentleman is absorbed in the contemplation of the kaleidoscope’s wonderful play of colors – the dark glass makes him even more near-sighted than usual. He is about to be knocked to the ground by a passionate draisine rider, who likewise has his eye fixed only on his machine. Let this be a warning for others. There is already supposed to be a police order in the works on the strength of which every blockhead is strictly forbidden, on account of the danger, from using both new inventions.

Two of the shapes in the picture – the cylinder of the kaleidoscope and the wheel of the draisine – will be familiar to analysts of Schubert’s music (Example 1). In 1999, Richard Cohn recast his newly invented theory of hexatonic cycles into the geometry of tonal space shown on the left in Example 1. Tailored especially for the analysis of Schubert’s music, the four cycles are interconnected through fifth relations into a cylindrical shape. Cohn’s geometry added a new dimension to the tonal space afforded by the traditional circle of fifths, which is shown on the right in Example 1. The invention of the circle of fifths, a diagram of iconic status in music theory, is generally credited to Heinichen in 1711, though a circular diagram without reference to major and minor is known as early as 1677 in the Russian tradition. It was originally coined the “musical circle,” for its circle of keys was in a different configuration, and, just like a scientific instrument, subsequent theorists claimed “improvements” to its design until it finally reached its currently familiar pattern.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Analyzing Schubert , pp. 1 - 5Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2011

- 1

- Cited by