Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Epidemiology is…

- 2 How long is a piece of string? Measuring disease frequency

- 3 Who, what, where and when? Descriptive epidemiology

- 4 Healthy research: study designs for public health

- 5 Why? Linking exposure and disease

- 6 Heads or tails: the role of chance

- 7 All that glitters is not gold: the problem of error

- 8 Muddied waters: the challenge of confounding

- 9 Reading between the lines: reading and writing epidemiological papers

- 10 Who sank the boat? Association and causation

- 11 Assembling the building blocks: reviews and their uses

- 12 Outbreaks, epidemics and clusters

- 13 Watching not waiting: surveillance and epidemiological intelligence

- 14 Prevention: better than cure?

- 15 Early detection: what benefits at what cost?

- 16 A final word…

- Answers to questions

- Appendix 1 Direct standardisation

- Appendix 2 Standard populations

- Appendix 3 Calculating cumulative incidence and lifetime risk from routine data

- Appendix 4 Indirect standardisation

- Appendix 5 Calculating life expectancy from a life table

- Appendix 6 The Mantel-Haenszel method for calculating pooled odds ratios

- Appendix 7 Formulae for calculating confidence intervals for common epidemiological measures

- Glossary

- Index

- References

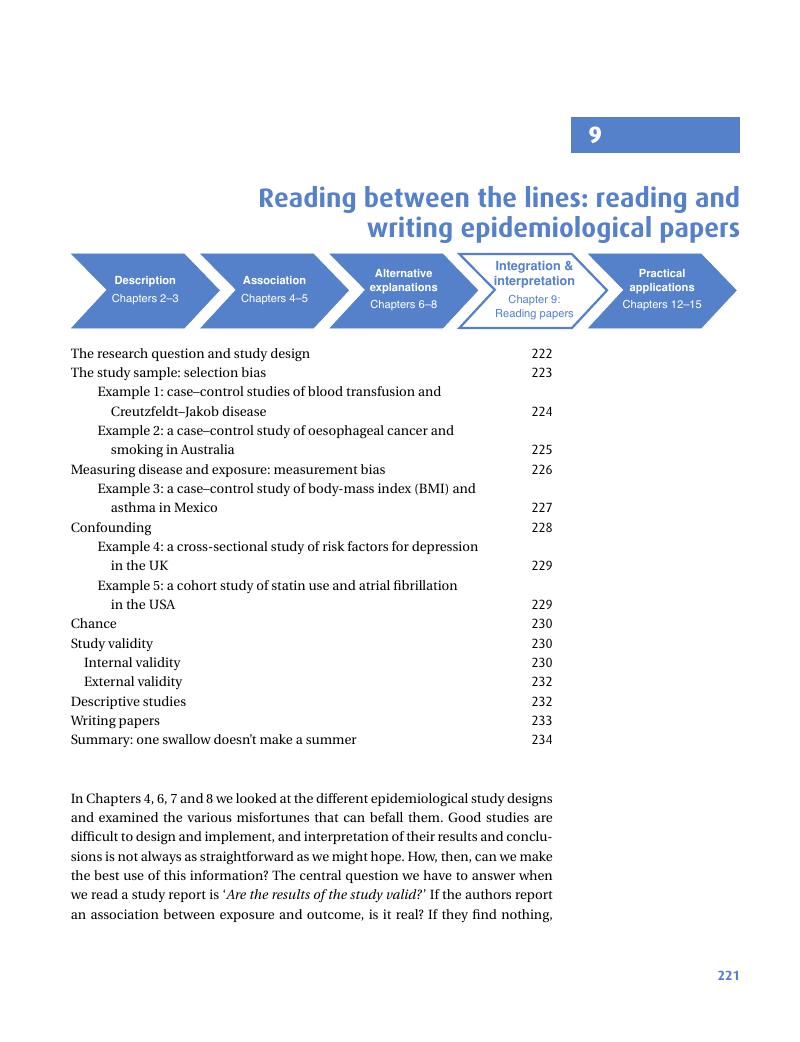

9 - Reading between the lines: reading and writing epidemiological papers

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Epidemiology is…

- 2 How long is a piece of string? Measuring disease frequency

- 3 Who, what, where and when? Descriptive epidemiology

- 4 Healthy research: study designs for public health

- 5 Why? Linking exposure and disease

- 6 Heads or tails: the role of chance

- 7 All that glitters is not gold: the problem of error

- 8 Muddied waters: the challenge of confounding

- 9 Reading between the lines: reading and writing epidemiological papers

- 10 Who sank the boat? Association and causation

- 11 Assembling the building blocks: reviews and their uses

- 12 Outbreaks, epidemics and clusters

- 13 Watching not waiting: surveillance and epidemiological intelligence

- 14 Prevention: better than cure?

- 15 Early detection: what benefits at what cost?

- 16 A final word…

- Answers to questions

- Appendix 1 Direct standardisation

- Appendix 2 Standard populations

- Appendix 3 Calculating cumulative incidence and lifetime risk from routine data

- Appendix 4 Indirect standardisation

- Appendix 5 Calculating life expectancy from a life table

- Appendix 6 The Mantel-Haenszel method for calculating pooled odds ratios

- Appendix 7 Formulae for calculating confidence intervals for common epidemiological measures

- Glossary

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Essential EpidemiologyAn Introduction for Students and Health Professionals, pp. 221 - 236Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2010