By and large, journalists did a reasonable job of reporting the findings of the NICHD SECCYD over the years, at least in the set of national and local newspapers that we tracked over a decade. Although the study’s complex findings were often over-simplified and occasionally reported without context or attention to the considerable nuance involved, we saw little evidence of significant misreporting or misrepresentation in the newspapers, especially systematically. Yet, when we focused our attention on specific kinds of framing in communication (risks versus benefits and mother-focused versus child-focused), we began to see how, at times and in particular circumstances, the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD raised questions about how early child care (and children’s issues more generally) is discussed in public forums.

Benefits and risks

Recall from Chapter 2 that, after the children in the NICHD SECCYD sample had passed the infant and toddler years in which early child care was a major issue for their parents, the main “omnibus” reports from the study consistently revealed a dualistic pattern of findings, with something more positive and something more negative alongside each other. The slight positive early child care effect on child development was that high-quality early child care was associated with children’s gains in cognitive test scores, and the slight negative early child care effect on child development was that large quantities of early child care were associated with increased scores on parents’ and other adults’ reports of children’s problem behavior. Although this basic dichotomy between early child care benefits and risks could conceivably support media stories presenting a mixed picture about early child care as a context of child development, it could be selectively mined to frame a story creating either a positive or a negative impression of how early child care arrangements shape children’s developmental trajectories.

The balance of positives and negatives in study findings

One simple place to start when considering whether or not media coverage was balanced between early child care benefits and risks is with the titles of the newspaper articles that we analyzed. To be sure, many titles conveyed the importance of both observed effects (e.g., “Child Care May Boost Academics, Hurt Behavior” in the Wall Street Journal in 2005). Yet, some articles focused on the negative effect (e.g., “Kids Thrive on More Mom, Less Day Care” in USA Today in 1999), and other articles focused on the positive effect (e.g., “Day Care Picture Brighter than Some Believe” in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 1998). In 1997, the Philadelphia Inquirer even ran titles that conveyed different conclusions about the same findings on consecutive days (“Toddlers Did as Well on Test as Those Who Stayed at Home With Their Mothers, A Study Found” and “High Quality Day Care Kids No Smarter Than Those Who Stay at Home With Mom”). Overall, the balance between more positively oriented and more negatively oriented newspaper article titles was fairly even, with most titles quite neutral. Moving beyond the titles to the article texts, however, revealed something different and more nuanced.

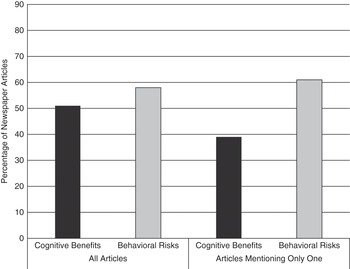

When we cross-tabulated the codes for attention to each kind of early child care effect in the NICHD SECCYD, we found that, across the whole time frame (from the mid-1990s through the late 2000s), newspaper articles on the study generally discussed both the cognitive benefits and behavioral risks. Of course, some of these articles devoted significant space to one of the findings (positive or negative) and then merely mentioned the other. Still, they did at least address both effects. Many articles, however, tended to focus on one effect or the other (see Figure 4.1). In 51 percent of the articles that we sampled and coded for this analysis, the cognitive benefits of high-quality care were discussed, and in 58 percent of the articles, the behavioral risks of high-quantity care were discussed. In the pool of articles in which only one of these two types of observed early child care effects on child development was discussed, it was more likely to be the behavioral risk (61 percent of articles) than the cognitive benefit (39 percent). Thus, usually both the positive and negative sides of early child care that emerged from the NICHD SECCYD were given attention in newspaper articles about this study, reflecting that the study reports – and associated press releases – covered both sides. When only one side was presented in a newspaper article, however, it was slightly more likely to be negative than positive.

Figure 4.1 Breakdown of newspaper articles by focal benefits/risks discussion

Examining the cross-tabulations of the benefit-to-risk codes across the newspapers that we studied revealed little evidence of geographic or other trends in the balance of reporting on the positive and negative aspects of early child care. The USA Today, Boston Globe, and Milwaukee Journal Sentinel were slightly more likely than the other newspapers that we sampled to highlight the behavioral risks of early child care quantity over the cognitive benefits of early child care quality. The Wall Street Journal and Houston Chronicle showed the opposite pattern, favoring the benefits over the risks more than other newspapers. For example, of the six articles in the Wall Street Journal, a traditionally more conservative newspaper, three focused on both behavioral risks and cognitive benefits of early child care, whereas the other three solely focused on the cognitive benefits. Of the eight articles in the Washington Post, a traditionally less conservative newspaper, five (63 percent) focused on both the cognitive benefits and behavioral risks, suggesting some balance, but the remainder placed a greater emphasis on the latter. Of course, content on editorial pages mostly reflects issues of ideological bents in newspapers, and, as already discussed, most coverage of the NICHD SECCYD occurred outside of these pages, especially during the 2000s. Overall, then, media coverage provided multiple angles on the NICHD SECCYD, in particular, and child care effects, in general. When focusing on one angle, however, the coverage was more likely to be in the direction of a more negative picture of early child care than a more positive one.

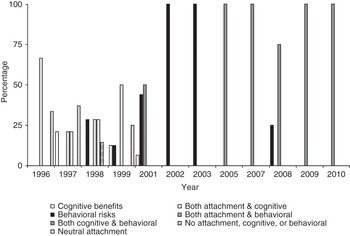

We also analyzed these patterns over time, expanding our consideration of the main findings of the study to look at how the media covered the early findings of a lack of any significant link between early child care factors and mother–child attachment (see Figure 4.2). The most striking examples of behavioral risks being favored over cognitive benefits occurred during the coverage of the 2001 report and then in the following years. Reflecting the substance of the 2001 SRCD press conference, but not the actual SRCD presentations or a subsequent article in American Educational Research Journal, the coverage tilted primarily toward the behavioral risks of early child care. This trend mostly ended by the time a second American Educational Research Journal article was published (in 2005). With one exception after that point, the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD was balanced between the cognitive benefits of early child care quality and the behavioral risks of early child care quantity. To elaborate on this pattern, we can focus on what was happening during particular time periods and draw on specific newspaper articles for illustration.

Figure 4.2 Findings reported in newspaper articles about the NICHD SECCYD by year

In the initial years of the NICHD SECCYD, the findings reported in the omnibus papers typically revealed few observable effects of early child care on children, either positive or negative, with the exception that some benefits were evident at the highest quality levels. The media coverage that followed tended to discuss these null effects as reassuring. Given the worries about early child care that were so common in US culture during that time, the absence of risks was viewed as good, and a general message emerged that parents need not fear early child care per se, but instead should worry about bad child care. Recall the comments of one Network investigator in Chapter 2 that the lack of early findings showing negative effects was taken as a “green light” for pushing an early-child-care-policy agenda.

This trend was supported by emerging evidence of some benefits of early child care when children were young without, at least at first, much evidence of risks. After the initial findings became public in 1996, an article in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel ran with the headline “Child Care May not Harm Ties to Good Mothers: Results of Comprehensive Study Counter Earlier Research that Non-Maternal Care Creates Insecurity” and led with the following: “The most far-reaching and comprehensive study to date has found that placing children in the care of someone other than their mothers does not, by itself, damage the emotional attachment between mother and child.” Similarly, the 1998 article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette that had the aforementioned optimistic title, “Day Care Picture Brighter than Some Believe,” is another good example. It read: “Let’s take this from the top one more time. Good day care is good for children and bad day care is not. Good day care does not undermine their attachment to their mothers, nor does it make them more aggressive. Bad day care can do both.” The same year, an article in the Boston Globe (“Quality Day Care Can Boost School Readiness” was the title) read: “High-quality care can improve cognitive and language development. ‘This was our most dramatic finding,’ says Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, professor of psychology at Temple University and one of the study researchers. ‘An appropriately stimulating day-care environment can make a difference in school readiness.’”

Eventually, however, that evenly positive/negative pattern of findings took hold in the SECCYD data, giving the researchers and journalists opportunities to discuss either or both patterns. Certainly, newspaper articles continued to pay attention to the cognitive benefits of high-quality early child care, but they tended to focus more on the behavioral risks of high-quantity early child care. Reading through the articles, we could see clear examples of the somewhat tilted focus that our coding indicated occurred around 2001. The opening paragraph of a 2001 article in the Boston Globe is typical of the stories being published around that time:

A new, unsettling study from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development says children who spend more than 30 hours a week in child care are more likely to display aggressive behavior than children cared for by their mothers. Even high-quality care arrangements are said to show this effect.

The same month, the Philadelphia Inquirer ran an article titled “Study: Behavior Declines with More Day Care Time.” Not until six paragraphs in were the cognitive benefit findings mentioned, with the sentence “Interestingly, the study also found that children who were in high-quality child care scored well on measures related to academic success.”

Strikingly, the trend in media coverage was clear enough that the media even covered the trend itself. Perhaps the best example was a New York Times column that spring in which a pair of medical doctors bemoaned what they saw as slanted coverage of the NICHD SECCYD. Under the title “Quality Child Care is Important in Developmental Years,” they wrote:

There has been a flurry of controversy about recently released findings from a study by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the effects of child care on young children’s development. Unfortunately, most of the attention has gone to a single finding: According to the sound bites, child care causes behavior problems. But what the preliminary report really shows is that 30 or more hours per week of child care were associated with higher rates of ‘problem’ behaviors than fewer hours of child care.

Although the imbalance between covering quality benefits and quantity risks was most pronounced during 2001, it did continue past this point. For example, fully six years after the 2001 presentation and associated press conference at the meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development in Minneapolis, a reporter at the Houston Chronicle ran a story about the latest study findings under the headline “Study: Day Care Ups Odds of School Behavior Woes; Quality of Care, Family Status Make No Difference in Effects Seen as Late as Sixth Grade.” It did mention the early child care benefits, but it dwelled far more on the risks:

A much-anticipated report from the largest and longest-running study of American child care has found that keeping a preschooler in a day care center for a year or more increased the likelihood that the child would become disruptive in class – and that the effect persisted through the sixth grade. The finding held up regardless of the child’s sex or family income, and regardless of the quality of the day care center. With more than 2 million U.S. preschoolers attending day care, the increased disruptiveness very likely contributes to the load on teachers who must manage large classrooms, the authors argue. On the positive side, they also found that time spent in high-quality day care centers was correlated with higher vocabulary scores through elementary school.

The media coverage during this period and afterward highlighted attempts by the Network scientists and by several outside experts to qualify the behavioral risks of early child care quantity. They typically did so by pointing out the small magnitude of the observed effects of early child care quantity on children’s behavioral problems or by comparing these effects to the magnitude of parenting effects on children. Indeed, as we discussed in Chapter 3, one of the most quoted non-Network people in the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD, Barbara Willer of the NAEYC, focused most of her comments on the small effect sizes as a means of stressing to readers that the apparent risks of early child care indicated by the NICHD SECCYD were, in her view, totally overblown. As one of the Network scientists aptly put it, “I think the take-away was that the effects we found were rather small in comparison to national expectations.”

All in all, we did see evidence that media were somewhat more interested in the developmental risks of early child care than the developmental benefits, particularly in 2001, even though both the risks and the benefits were part of the Network’s omnibus reports and the attendant dissemination activities, including the 2001 press conference at the Society for Research in Child Development meeting. Yet, the magnitude of this differential focus on risks and benefits was smaller than we had expected based on our own prior perceptions of the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD both before and after we joined the study. It was also smaller than what we saw as the common consensus about media bias in coverage of the study within the NICHD Early Child Care Research Network.

Other positives and negatives

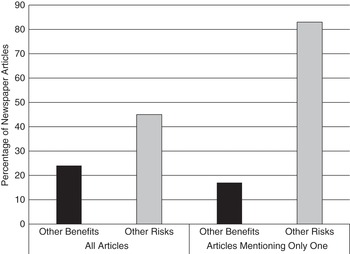

Interestingly, this slight tendency toward the negative in the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD seemed more evident once we moved past the main study findings about the links between early child care quality and children’s cognitive test scores and between early child care quantity and children’s behavioral problems. Specifically, we saw that other kinds of child care effects (empirically demonstrated or generally assumed regardless of empirical support) were brought up in articles about the NICHD SECCYD reports (see Figure 4.3). Many of the newspaper articles in our sample went beyond the NICHD SECCYD findings, even when the NICHD SECCYD was the main focus of the articles. Some other early child care benefits for children were introduced in 24 percent of the articles that we reviewed, but some other early child care risks for children were introduced in 45 percent of the articles. Importantly, articles that discussed the former type of effect rarely discussed the latter, and vice versa. Over 40 percent of the articles introduced new discussions about child care risks beyond the NICHD SECCYD findings without any mention of other benefits, with only 9 percent of the articles doing the reverse.

Figure 4.3 Breakdown of newspaper articles by other benefits/risks discussion

These articles tended to supplement the discussion of the main NICHD SECCYD findings in three main ways:

Bringing in other information from the NICHD SECCYD, often tangential to the main study findings about cognitive benefits and behavioral risks, that countered the former or made the latter seem not as bad.

Introducing findings from other studies about early child care effects on child development that may have run counter to the dualistic NICHD SECCYD findings about the cognitive benefits of early child care quality or the behavioral risks of early child care quantity.

Discussing possible (or assumed) child care effects on children that were not attributed to the NICHD SECCYD, or to any other study for that matter.

The most common way that newspaper articles supplemented the main NICHD SECCYD findings with other information from the NICHD SECCYD was based on the text of the omnibus reports and interviews with the Network scientists. It involved stressing that aspects of the family environment and parenting were far more important predictors of children’s developmental outcomes than any dimension of early child care. This “parents matter most” theme carried throughout the entire decade and a half of media coverage of the study. Indeed, a 2010 article in the Charlotte Observer emphasized this theme when reviewing the findings of the study over time: “But three other findings deserved attention as well, the researchers said, and remain applicable nearly a decade later. Good parenting matters: Children whose mothers are responsive and sensitive were less likely to be rated as aggressive by their parents and teachers.” This passage suggests that some of the Network investigators underscored the importance of parenting for children to counterbalance the weaker developmental risks of early child care that had lingered into adolescence. Echoing this interpretation, one Network scientist whom we interviewed commented on the other findings discussed by the investigators: “… some emphasized small effect sizes, the fact that family factors always predicted much better than child care ….”

The centrality of parenting to the discussion of early child care in the omnibus reports and associated media coverage stretched to other aspects of parenting that were linked to early child care in the NICHD SECCYD, such as the neutral effects of early child care on mother–child attachment and the early link between child care quantity and less sensitive mothering. These associations might not have been focal findings, but they were frequently brought up when discussing them. For example, a 1997 New York Times article ran with the positively focused headline, “Good Day Care Found to Aid Cognitive Skills of Children,” but it also included this passage: “The more time a child spent in day care, the study found, the less sensitive mothers were toward infants at 6 months, the more negative the parent was toward the child at 15 months and the less sensitive the mother was toward toddlers at age 36 months.”

A somewhat different approach in other newspaper articles was to pair the findings from the NICHD SECCYD with findings from other studies that cast a positive light on early child care. For example, a New York Times article in 2005 discussed the NICHD SECCYD findings in light of a study published by Bruce Fuller and colleagues (Reference Fuller, Kagan, Loeb and Chang2004) in the journal Early Childhood Research Quarterly that demonstrated that early child care centers provided safer environments for many children from low-income families in the US than home-based care providers. The NICHD SECCYD findings were also frequently linked to findings from the famous Perry Preschool Project, which revealed positive effects of early childhood intervention on economically disadvantaged children’s outcomes as they grew into adulthood, and the Tulsa Pre-K program, which showed gains in many academic outcomes among children in state-funded preschools (Gormley, Gayer, Phillps, & Dawson, Reference Gormley, Gayer, Phillips and Dawson2005; Heckman, Reference Heckman2006). In a somewhat similar vein, coverage in the early years, when the findings were primarily limited to mother–child attachment, sometimes connected the NICHD SECCYD results to other studies on maternal employment and its lack of a significant association with many indicators of children’s development. For instance, prior to presenting results from the NICHD SECCYD, a 1999 article (titled “What Good Old Days”) in the Boston Globe reported: “The most recent study was done by Elizabeth Harvey at the University of Connecticut based on data from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth and published by the American Psychological Association a few months ago. It found that employment by mothers during children’s early years had no impact on their development.”

At the same time, newspaper articles were slightly more likely to pair the NICHD SECCYD findings with results from other studies that cast a more negative light on early child care. For example, findings from one omnibus report were discussed in relation to a study published by Sarah Watamura and colleagues (Reference Watamura, Donzella, Alwin and Gunnar2003) in the journal Child Development (which also published multiple NICHD SECCYD reports) showing that children who spent full days in child care had elevated levels of cortisol, a hormone that is part of the body’s stress response system. In 2008, the New York Times published an article reviewing the state of research on child care quality that featured the NICHD SECCYD evidence with the caveat of divergent findings from other studies:

One of the first decisions working parents must make is whether to place their child in a day care center. Preschool programs and day care centers have been studied extensively by researchers, and the reports are usually a mixed bag of risks and benefits. Occasionally, however, a troubling finding may set off alarm bells. A 2006 study of a popular government-subsidized day care program in Quebec found, among other things, that children in the program showed more anxiety and aggressiveness and were slower to learn toilet training than other Canadian children.

Such links to other studies were especially common in 2001, when the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD arose from a presentation at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, which featured many different types of studies about the contexts of early child development, including early child care. For example, one article in the Star-Tribune of the Twin Cities (where the meeting was held) discussed findings about early child care and violent media together: “Violent video games, movie fight scenes, and even time in day care – all part of modern American childhood – tend to crank up the level of aggression in youngsters, according to several studies to be reported at an international conference of child-development professionals that starts today in Minneapolis.” A Washington Post article titled “Child Care Worries Adding Up” coupled the NICHD SECCYD findings with information from a study about worrisome trends in the staffing of child care centers. “First there was the report that toddlers in child care are more likely to be aggressive and disobedient by kindergarten than those who stay at home with their moms. Now, a study released yesterday says child-care centers are losing well-educated teaching staff and administrators at an alarming rate and hiring replacements with less training and education.”

Some studies linking the NICHD SECCYD findings with other early child care research did so in ways that suggested reasons to both worry about and feel good about early child care. The best example is a long feature in the Wall Street Journal in 1997 that summarized child care research as part of a White House conference on children’s brain development. On the positive side, this article emphasized the general neurological benefits of quality care (from parents or others), and its title clearly focused on that angle: “Good, Early Care Has a Huge Impact on Kids, Studies Say.” Yet, at the same time, the article primarily discussed this pattern in terms of the risks of low-quality care.

Neuroscientists are finding that good nurturing and stimulation in the first three years of life, a prime time for brain development, activates in the brain more neural pathways, or synapses, that might otherwise atrophy, and may even permanently increase the number of brain cells. All this has chilling ramifications for the roughly three million kids three and under in poor-quality child care (based on Families and Work Institute estimates that about one-third of child care is potentially damaging). For those children, child care may: Hurt intellectual and verbal skills, Increase their mothers’ negativity toward them, Put those with poor or depressed mothers at greater risk by further eroding the mother–child bond, Deprive them of the stimulation needed to develop their brains to the fullest.

Finally, newspaper articles often supplemented coverage of the NICHD SECCYD findings with additional discussion of early child care and its effects on children. Unlike all the examples given thus far, however, this additional discussion was not grounded in any research. It typically involved broad generalities about “common sense” assumptions about parents, children, and early child care that may or may not have been empirically grounded or accurate. One of the most common themes of this additional discussion was the notion that children’s time in early child care – related to parents working – meant time lost with parents. For example, a 1997 essay in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette was titled “Our Child Care Culture Tells Kids that Work Matters Most.” It read: “Working parents at all income levels have less and less time to spend with their children. Inadequate family leave policies mean that many infants get only a few months of full-time, one-on-one attention, if that.” We should reiterate when introducing this theme that research shows that parents today spend more time with their children than parents did in the past (Sayer et al., Reference Sayer, Bianchi and Robinson2004).

In our view, journalists’ motivations to provide some broader context for the NICHD SECCYD findings were admirable. They seemed to be trying to help their readers understand what the research was saying and what it meant by going further than the study itself. Yet, this motivation often resulted in a reinforcement of the trends highlighting the negative aspects of early child care rather than the positive ones, even though both aspects of early child care were part of the NICHD SECCYD reports and associated dissemination activities.

Mothers in the spotlight

Developmental research on early child care – including the NICHD SECCYD – evolved over a historical period in which American society was also undergoing rapid cultural, economic, and demographic changes. Not surprisingly, therefore, the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD tended to reflect both concerns over and excitement about these changes. What was made clear from our analysis of newspaper articles about the NICHD SECCYD in the 1990s and 2000s was that this tendency to connect early child care research to broader societal issues primarily brought mothers, especially middle-class mothers, to the fore.

Recall that a major impetus for the creation of the NICHD Early Child Care Research Network in the late 1980s was the need to understand the effects of early child care on children’s development because of the increasing number of children in such settings over the previous two decades. As we discussed in Chapter 1, this trend was the result of several large-scale population changes in the latter part of the twentieth century. Most notably, a sharp rise in maternal employment began in the 1970s (Bianchi, Reference Bianchi2000; Waldfogel, Reference Waldfogel2006), which was also a driving force of the funding of the NICHD SECCYD. Other important, but less acknowledged, population changes contributing to the early child care trend were the growing prevalence of single parenthood, divorce, and nonmarital fertility (Cherlin, Reference Cherlin2009; Crosnoe & Cavanagh, Reference Crosnoe and Cavanagh2010; McLanahan, Reference McLanahan2004). Several major policy changes also occurred before, during, and after the launch of the NICHD SECCYD that had implications for the rise in nonparental care of US children. One was welfare reforms in 1996 (during the administration of President Bill Clinton), which effectively mandated employment for low-income women in exchange for time-limited cash benefits. In other words, this federal policy was intended to promote employment among low-income women in lieu of public assistance. Another policy shift was the expansion of government-supported early education programs for children from low-income families over the last two decades (e.g., Early Head Start and state pre-K) and an increasing emphasis on school readiness in these programs. Not only was the scope of these programs expanded, but their reach extended to younger children than most prior efforts (Love et al., Reference Love, Kisker, Ross, Raikes, Constantine, Boller, Brooks-Gunn, Chazan-Cohen, Tarullo, Schochet, Brady-Smith, Fuligni, Paulsell and Vogel2005; Ludwig & Phillps, Reference Ludwig and Phillips2007; Zigler, Gilliam, & Jones, Reference Zigler, Gilliam and Jones2006).

Two themes

Among the myriad demographic and policy forces at play in the long-term increase in the proportion of children in early child care over the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century, the rise in maternal employment levels was, by far, the one that was most often linked to the NICHD SECCYD findings on early child care and child development. Indeed, our review of newspaper articles, collectively, demonstrated a strong tendency to explicitly and implicitly equate child care issues with maternal employment, so much so that the NICHD SECCYD findings often seemed to be presented as a subset of a debate on maternal employment or as only relevant when linked to this debate. The majority of articles (57 percent) were coded as being primarily about working mothers rather than child care itself, even when the NICHD SECCYD findings were the nominal impetus for and focus of the article. This pattern did not differ substantially by the journalists’ gender (whether it might have differed by reporters’ own family status or child care responsibilities is an open question we could not address here).

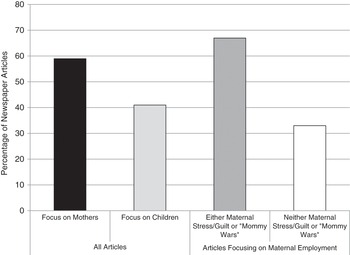

Across this subset of articles that focused on maternal employment, two overriding themes were evident (see Figure 4.4):

The guilt and stress of working mothers (nearly 70 percent of newspaper articles focusing on maternal employment and 35 percent of all newspaper articles).

The so-called mommy wars, that is, debates about whether working mothers or stay-at-home mothers were doing the best by their children (33 percent of maternal-employment-focused articles and about one-fifth of all articles).

These two themes strikingly illustrated framing by journalists that went beyond the NICHD SECCYD reports, press releases, or study investigators statements. In this case of framing in communication, therefore, the framing was primarily coming from the media side and not the research side. An example of the first theme is an article, “A Guilt-Edged Occasion. It Would Seem That Today’s Moms Have Much to Celebrate. Instead, Many Are Feeling Insecure and Torn,” that appeared in the Boston Globe in 1997 after the release of the early findings on mother–child attachment.

Figure 4.4 Breakdown of newspaper articles by maternal or child focus

Note that the NICHD SECCYD report that prompted this article discussed largely null results – early child care did not seem to have many effects on very young children. One of the initial study investigators, Deborah Phillips (then the Director of the Board on Children, Youth, and Families at the National Research Council), explicitly discussed the findings in this frame, lamenting to the Boston Globe that “Mothers really do have a lot of deep-seated insecurities about day care; it’s an issue that produces knots in the stomach.” Several years later, an article that also appeared in the Boston Globe echoed this earlier one in a manner that evokes the West Wing quote in Chapter 1: “This is precisely the sort of news that once gave me a case of gut wrench and guilt sweats. But over the years, I have developed some immunity … Nevertheless, for all those mothers who are now sure that they are sending the kids off to Lil Mass Murderer Play Skool, a bit of deconstructing is in order.”

Another 2001 article in the Washington Post ran under the title “Working Moms and Day Care: It’s Life with a Guilt Edge.” This article described how young children who spent time in early child care settings were more “aggressive, defiant and disobedient by the time they reach kindergarten than kids who stay home with their mommies. They’re also more likely to be disliked by their classmates.” What is interesting is that, in the 2001 press conference at the Society for Research in Child Development meeting, Jay Belsky talked about parents rather than mothers, but the newspaper articles discussed the findings in terms of “mommies.” One Boston Globe article (“Child Care without Guilt”) published at that same time drew indirect attention to the imbalanced focus on mothers and guilt when discussing the NICHD SECCYD findings: “One implication seemed clear: Mothers – or fathers – should work less and spend much more time at home, caring for their children. But instead of guilt trips for moms and gender wars over the role of dads, America needs world-class child care.”

The second theme was closely related to the first theme. It typically involved comparisons of working mothers with nonworking mothers. An example of this theme was published in the Boston Herald in 1997. It was titled “Must Both Parents Work? New Studies Stir Debate.” Again, the NICHD SECCYD findings in question were largely null. A few articles even used the term “mommy wars,” such as a 2001 article in the Philadelphia Inquirer (titled “Mothers on the Firing Line – Again”) which read: “The mommy wars have heated up again with a new study that purports to show that children in non-maternal care are more likely to be aggressive and disobedient by the time they reach kindergarten than children who spend less time in day care.” Sometimes, this theme was introduced by others outside the Network whom the journalist consulted about the NICHD SECCYD findings, such as the quote from David Popenoe that “mothers should be the primary caretakers of infants during at least the first year to 18 months of life” in a 1997 article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette that we shared in Chapter 3. This quote continued with “It’s better to drive junker cars and have sound kids, than to have pricey cars and neglected kids.”

This theme was perhaps best summarized by Washington Post columnist E. J. Dionne in a reflection about how the NICHD SECCYD findings were covered in the wake of the 2001 Society for Research in Child Development presentation and press conference:

Two recent studies underscore, in quite different ways, the imperative of moving from polarization to problem solving. Take, first, the already famous child care study released this month by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The study found that the more time toddlers spend in child care, the more likely they are to be aggressive, disobedient and defiant when they enter kindergarten. The same study, by the way, also found that children enrolled in high-quality child care performed better on tests of language, knowledge and memory than children who stayed at home with their mothers. The findings set off explosions all over the country. Working mothers complained, as one did to the Los Angeles Times, that the study was ‘just another bad rap for working moms.’ One stay-at-home mom countered that the study confirmed what she had always thought. ‘Oh, it’s all so true.’ Who can blame parents – mothers especially – for reacting personally? The culture-war style makes it inevitable that one side or the other will feel under assault.

In terms of connecting these two mother-focused themes, the leads (and associated titles) to several newspaper articles published during the early years of the NICHD SECCYD (and especially 2001) are telling. They viewed the issues of early child care, maternal employment, and maternal choices as almost interchangeable:

Are children worse off because mothers now work? Well, overall, the intellectual development of kids in day care doesn’t seem to suffer when compared with their stay-at-home peers, suggest new, authoritative findings from an ongoing study by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

It seems fitting, with the ninth annual Take Our Daughters to Work Day last week, that we’re seeing a little uptick in working-mother news. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development has released yet another chapter in its long-running study of the effect of child care on kids, ambiguously suggesting that too much time (amount unspecified, of course) in child care may make youngsters more aggressive.

Ah, yes, another day, another dollar, another anxiety attack. Such is life for working mothers in the dawn of the 21st Century.

At least early on in our time frame of interest, the lines between early child care (an issue about children) and maternal employment (an issue about parents) blurred in the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD. Moreover, the articles that we reviewed posed questions and engaged in discussions about work–family conflict and parental choice almost entirely in terms of women. True, the NICHD SECCYD itself focused on mothers rather than fathers (at least in its early years), but the fact that almost no newspaper articles pointed out that fathers should have been more central to the study also plays into the blurring of those lines.

Trends by time, place, and scope

Importantly, both the mother-focused framing themes that we just laid out became much less prevalent in newspaper coverage of the NICHD SECCYD after the presentation of the 2001 omnibus report and subsequent press conference at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development in Minneapolis. In fact, we coded no articles as invoking the “mommy wars” after this point. Interestingly, few differences in these trends were apparent across newspapers, regardless of geographic region, scope of circulation, or perceived liberal/conservative leanings.

An examination of the cross-tabulation of these two mother-focused themes in the newspaper articles covering the NICHD SECCYD findings yielded an informative and interesting pattern. Among those articles coded as primarily addressing maternal employment rather than early child care itself, only five focused solely on the findings of the cognitive benefits of early child care quality in the NICHD SECCYD, but 33 percent of these articles discussed the behavioral risks of early child care quantity in the study and 37 percent discussed both the quality benefits and the quantity risks. In other words, articles leaning more toward a positive frame of early child care were less likely to blur the lines between a mothers’ issue and a children’s issue than articles that leaned toward a more negative or neutral frame. A similar but somewhat less pronounced pattern was seen in those newspaper articles coded as focusing on maternal guilt and stress. For example, a 2001 article in USA Today titled “Balancing Family, Work: Day-Care Study Raises Questions, and Anxious Moms Need Answers” read: “About two out of three U.S. mothers with preschoolers are employed. Their anxiety could hardly be eased … by hearing a couple of weeks ago that as hours in day care rise, so do behavior problems in kindergarten – a key finding of the federal study of 1,364 children starting in early infancy.”

When we coded newspaper articles as being about the “mommy wars,” we found that not a single one focused solely on the NICHD SECCYD findings about the cognitive benefits of early child care quality (compared to 35 percent discussing the findings of the behavioral risks of early child care quantity alone and 35 percent discussing both the quality benefits and the quantity risks). Moreover, none of these “mommy war” articles mentioned any other positive aspect of nonparental care for children, but 64 percent noted some other negative feature of such care. A similar trend was seen in newspaper articles that were coded as being about maternal employment, although this trend was not as pronounced in that subset of articles. In short, although all articles that connected early child care to mothers’ lives seemed to have a more negative frame than those that did not, articles coded as invoking the “mommy wars” presented somewhat of a less balanced view of the NICHD SECCYD findings than those coded for maternal employment (including those focusing on maternal guilt and stress). The difference between these two categories of mother-focused articles was about whether the experiences of mothers were discussed primarily in terms of the effects of early child care on children, as was the case in articles about maternal employment, or whether a link between maternal employment and perceived harm to children was discussed regardless of early child care, as was the case in articles about the “mommy wars.”

Overall, these analyses of media coverage highlight that articles about the NICHD SECCYD largely reflect one major undercurrent in our culture. Specifically, discussions and debates about early child care are not about early child care per se but, instead, about what and where the “proper” place of women is in modern society.

Broader context

As an illustration of this point about the focus of media coverage on mothers’ choices, the opening line of a 2001 Boston Globe article entitled “New Squabble Over Day Care,” reporting on the NICHD SECCYD findings after the Society for Research in Child Development meeting, read: “In an age when few would question a woman’s right to hold any job she can do, a mother’s right to work outside the home while raising children remains controversial.” As we have already discussed, the two themes that developed in the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD around mothers and their guilt, stress, and proper role tapped into larger societal debates. One of the primary debates that echoed in this Boston Globe article was about gender inequality in the home and in the workplace. Addressing gender inequality was a central goal of the Feminist Movement that was ignited in the late 1960s and in full force during the 1970s and 1980s. Thus, we were not entirely surprised that the very debates about women and mothers raised by this social movement played into the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD, especially during the early years of the study and the release of its initial omnibus reports (i.e., 1996–2001).

The following paragraph from a 1997 article in the Boston Globe that we mentioned earlier (“A Guilt-Edged Occasion. It Would Seem that Today’s Moms Have Much to Celebrate. Instead, Many are Feeling Insecure and Torn”) captures this broader context of the debate about feminism in which the framing of the NICHD SECCYD findings around mothers emerged:

Conservatives fault liberals such as Clinton for creating the social and economic policies that they say crushed family values and pushed women to work for pay when they wanted to be home raising children. Post-feminists disagree; they say their sisters in the 1970s and ’80s sowed these seeds of conflict when they overstated to women the satisfaction from careers and downplayed the maternal instinct. Another camp, psychologists, blame Dr. Benjamin Spock and his child-rearing prescriptions for changing the culture from adult-centered to child-centered, making it impossible for any women ever to mother well enough.

While the Feminist Movement pushed for rethinking and expanding traditional gender roles in both the home and work domains, other countervailing forces were also clearly at play, notably the Antifeminist Movement, which fed into discussions of guilt, stress, and the “mommy wars.” Not surprisingly, a number of articles on the NICHD SECCYD were quite critical of the Antifeminist Movement for this reason. In the aforementioned article, “What Good Old Days?” published in the Boston Globe in 1999, the journalist discussing the NICHD SECCYD findings was quite disparaging of both the contemporary conservative antifeminist backlash and traditional ideas about women and mothers from the past:

The idea that women have more problems today because of “freedom” than they did 30 years ago doesn’t square with the evidence. Homemakers in the ‘50s were four times as likely to be depressed as men. By the early ‘70s, the mental health of homemakers was so bad that sociologist Jessie Bernard decreed marriage a health hazard for women. But the antifeminists have no patience with data. If it doesn’t fit their ideological agenda, they ignore it – and are often well paid to do so.

Other journalists, like the one in “What Good Old Days,” also used the NICHD SECCYD findings, to “demystify” the past as the Feminist Movement frequently sought to do. Their intent often was to push the debate further. For example, another journalist lamented in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (“Child Care and Aggression: Reality Check,” 2001):

When working mothers and child care are finally recognized as standard for the majority of women in American society, when public and private sectors are willing to support it sufficiently to guarantee every child access to high quality care, when child care becomes an institution and a cultural ideal – only then will would-be experts stop equating child care with feminism and marginalizing it. Only then will all infants and young children receive daily the loving, responsive, stimulating care that they all need – whether from mother and father, from grandma or Aunt Bertha, or from a professional child-care provider.

Thus, the fact that much of the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD findings about early child care in the late 1990s and early 2000s was channeled through the frame of mothers and work is hardly shocking. The Feminist Movement – and the backlash against it – was part and parcel of the population changes occurring at the end of the twentieth century (e.g., rising maternal employment, divorce rates, and single parenthood). It served to focus attention on women’s roles at home and at work and on necessary support for both, notably early child care. This attention, from all sides of the debate, undoubtedly, contributed to the political pressure for a national study, such as the NICHD SECCYD, to evaluate the effects of early child care on children’s development and was destined to continue during the public release of its findings.

Who’s in, who’s out

The purpose of this chapter was to lay out what we saw as the main foci and subtext of the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD findings on early child care and children’s development. We have shown how the newspaper articles that we sampled from across the nation got the basic facts of the study right but, in the process, framed those facts in different ways, with a tendency to focus on early child care risks over early child care benefits within the context of a broader discussion about women generated by the Feminist Movement. To close this chapter, we want to briefly shift away from what the newspaper articles focused on to who and what was left out of those articles, which demonstrates that the public discussion of children and mothers often concerns only a slice of the population.

First, as we have already noted, fathers were a set of “invisible” individuals in the media coverage of early child care research. They were mentioned in only 24 percent of the newspaper articles that we reviewed, even though mothers were discussed in all the articles (see the example from the 2001 Boston Globe article, “Child Care without Guilt,” quoted earlier). Again, we want to stress that fathers were not a major focus of the NICHD SECCYD by design of the Network investigators, and data were not collected from fathers until investigators reconsidered their initial strategy once the study was well underway. Indeed, one journalist bemoaned, “Unfortunately, I think the study kind of missed the boat by excluding fathers.” Still, given how the discussion of the NICHD SECCYD findings in the newspaper articles that we sampled often went far beyond the actual data, the absence of fathers in the media coverage of the study was notable, especially in the later phases of the study when fathers were more involved in the data collection and fathers’ involvement in child care continued to increase in the US (see Bianchi, Robinson, & Milkie, Reference Bianchi, Robinson and Milke2006). Beyond reinforcing the point that nonparental care was generally seen in light of women and their mothering role, this omission indicates an overall lack of acknowledgment of the role that fathers play in caring for their children. By largely limiting the discussion to mothers and their work lives, opportunities for broader public discussions of how best to meet the needs of children, parents, and families from diverse segments of the population were lost (Parke, Reference Parke2013; Waldfogel, Reference Waldfogel2006).

Likewise, low-income women were infrequently coded as a topic of articles covering the NICHD SECCYD. True, the study sample was primarily middle-class families, was not designed to speak to the challenges faced by low-income families, and reported few income-related differences in child care effects on children. Much like fathers, however, we thought that journalists could have discussed this population more, given how often they brought up many issues not covered in the NICHD SECCYD omnibus reports. As we discussed earlier in this chapter, the initial phases of the NICHD SECCYD occurred during a historical period (the 1990s) in which large numbers of low-income mothers of young children were being compelled to work through policy changes. These policy changes, collectively known as welfare reforms, were predicated on political arguments that maternal employment would be beneficial for women and their children (Duncan, Huston, & Weisner, Reference Duncan, Huston and Weisner2007; Slack et al., Reference Slack, Magnuson, Berger, Yoo, Coley, Dunifon and Osborne2007; Zedlewski, Reference Zedlewski2002). We were surprised that this major point of discussion around the issue of maternal employment was not engaged more in media coverage despite the broad “mommy wars” discussion going on more generally. One possible reason has to do with who reads newspapers and what interests them. As one reporter at a national newspaper explained, “The topic [of child care] was a hot one because our readership slanted heavily professional/business people, with plenty of working mothers and spouses of working mothers.” Consequently, journalists and editors might perceive their audience as not caring about low-income parents.

Finally, the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD equated the early child care issue with the timely issue of maternal employment, but rarely connected it to another timely issue of the era: early childhood education. As one reporter who covered the NICHD SECCYD for a national newspaper acknowledged, “the field is a moving target.” The last two decades, in particular, witnessed significant increases in public discussions of and policy action toward increasing the availability of early childhood enrichment programs – typically housed in child care centers – at the national level and in many states (Duncan & Magnuson, 2014; Zigler et al., Reference Zigler, Gilliam and Jones2006). This discussion and expansion of publicly supported early education programs for young children stemmed from a growing sentiment, empirically based and otherwise, that such programs, when of high quality, can enhance children’s development, in general, and for children from low-income families, in particular (Duncan & Magnuson, 2014; Heckman, Reference Heckman2006; Ludwig & Sawhill, 2007; Takanishi & Bogard, 2007). The fact that these discussions primarily occurred parallel to, but rarely overlapped with, the media coverage of the NICHD SECCYD suggests that dialogues about child care were drawn largely along socioeconomic lines – more about work–family conflicts and less about educational investments in children. Perhaps it also reflects the tendency for the NICHD SECCYD findings to be framed as more of a family or parental issue rather than as one concerning children’s educational enrichment.

In sum, the media coverage of the dynamics of early child care revealed in the NICHD SECCYD findings was quite broad in some ways while also being quite narrow in others. It was primarily situated in the concerns of middle-class mothers of young children, expanding beyond the best interests of children while leaving out other parents and the possible needs of their children. As we highlighted in this chapter and earlier, the NICHD SECCYD and its media coverage unfolded during a particular period in the US and around a particular topic – early child care – shaped by many colliding forces.