Of all the writers we are looking at in this book, Jürgen Habermas is the only one who arguably belongs, equally comfortably, in philosophy and sociology. Habermas may be said to represent the most genuine effort to develop the kind of philosophical sociology in which I am interested: the relevance of keeping both traditions together because of their potential to offer a claim to knowledge that is not only empirically sound and theoretically consistent but also normatively relevant.Footnote 1

Indeed, the question of the relationships of philosophical and scientific knowledge-claims is one of those themes that has accompanied Habermas throughout his intellectual career. This was one of the original motifs behind Habermas’s (Reference Habermas1974) early work Theory and Practice, which focused on the implications of the transition from a ‘classical’ (i.e. philosophical) to a ‘modern’ (i.e. scientific) conception of politics. A change that is conventionally marked by the publication of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan in the middle of the seventeenth century, Habermas reconstructs this change as a move away from a traditional idea of politics based on prudence and virtue to a modern one based on law-like or instrumental knowledge about human nature and society. The task of a critical theory of society was then to rethink the relationships between science and politics by finding a new standpoint that is neither restorative nor merely technocratic (Reference Habermas2003a: 277–92). Habermas’s (Reference Habermas1972) first systematic project for the renewal of critical theory, as outlined in Knowledge and Human Interest, focuses explicitly on the possibility of getting the best of both traditions: the empirical/theoretical knowledge claims that we associate with the modern sciences and the reflective/normative stance that we associate with modern philosophy after Kant. Fast-forward two decades, and a similar sensibility still runs through Habermas’s (Reference Habermas1992a) writing on the postmetaphysical constellation: as science continues to develop and, through technological innovations, continuously transforms the world we live in, we must consider the roles, if any, that remain open to philosophy – not least in terms of raising the kind of existential questions that trouble human beings as human beings. Even his more recent work on naturalism and religion bear the mark of the constant attempt to bring together their different claims to knowledge (Reference Habermas2008).

There is a second sense in which Habermas’s work is fundamentally informative for my project of a philosophical sociology. Over the past five decades or so, as most mainstream social and political thought has grown increasingly sceptical of universalistic arguments, Habermas is still committed to universalism as an intellectual orientation. In the wake of the humanism debate that we reconstructed in Chapter 1, Habermas has remained unimpressed by the influence of Heideggerian tropes in writers such as Derrida, Foucault and Gadamer. Rightly in my view, Habermas takes issue with two of the propositions that have since become mainstream in the social sciences. On the one hand, there is the irrationalism that can be easily derived from ideas of deconstruction or archaeology. As they emphasise the contingency, exclusions and power differentials that underpin modern claims to knowledge, Habermas queries Derrida and Foucault for having dramatically undermined the very possibility of making normative claims. Ideas such as responsibility and autonomy, let alone fairness and democracy, can hardly be maintained if we are serious about the deep sources of modern irrationalism. Through his polemical style, Habermas did not always appreciate the extent to which Foucault and Derrida themselves tried to avoid these pitfalls and sought to rekindle some kind of rational core within their works; not least with regard to the progressive side of their politics.Footnote 2 But Habermas does have a point when he highlights their performative contradiction: they seek to reclaim the normative implications of their arguments by appealing to the very kind of normative/communicative rationality whose validity they have just negated.Footnote 3 As their ideas have ‘trickled down’ and become mainstream in the humanities and social sciences of the past fifty years, we are above all left with the key irrationalist implication that knowledge is power: indeed, that it is only power. On the other hand, Habermas criticises the relativism that in his view is built into Gadamer’s hermeneutical project (Reference Habermas1988). Habermas is here troubled by both the epistemological and normative implications of the historicist claim that, because linguistic and cultural traditions are seen as self-contained, they cannot genuinely communicate and understand each other: epistemologically, he rejects the idea that there is such a thing as a close tradition and defends the notion that all human languages can be reconstructed through a formal or universal pragmatics; normatively, this is deeply problematic as reminiscent, for instance, of conservative ideas of authenticity or indeed ethnic conceptions of the nation. We can in fact read Habermas’s critique of Gadamer as a wider critique of the excesses of social constructionism; that is, as a rejection of the point of view that the world exists only to the extent it exists for us within our own particular linguistic universe. Habermas’s resolute rejection of all these positions – irrationalism, constructionism and conservative notions of authenticity – is also central to my project of a philosophical sociology.Footnote 4

There is, finally, a third tenet of my project of a philosophical sociology where Habermas’s arguments do not seem to fit quite so well – at least not at first sight. It is a key contention of this book that we still need a fuller articulation of the main anthropological dimensions that can sustain a universalistic principle of humanity in the social sciences. In order to do this, I have argued that we ought to be able to isolate, as it were, the irreducibly human core that transpires from our various understandings of social life. Through the importance he has given to ideas of linguistic understanding and communicative action – and indeed by his commitment to the so-called linguistic turn – Habermas does not appear to be particularly interested in the delimitation of those uniquely anthropological capacities that makes us human.Footnote 5 Closer to the mark, it seems to me, is the view that Habermas’s theory of communicative action still needs to confront explicitly the way in which its own emphasis on social action does depend on implicit ideas of human nature (Joas Reference Joas, Honneth and Joas1991). An argument that applies also to most of the other writers I am surveying in this book, the anthropological question is not central to Habermas’s concern. But in this case it is the very idea of a linguistic turn, which in Habermas’s version is construed as a rejection of the so-called paradigm of consciousness, seems to speak in favour of what Margaret Archer has referred to as sociological imperialism: an idea of the human that is seen as society’s gift.Footnote 6

The original idea of the linguistic turn can be traced back to the reception of Kant’s first critique on pure reason. There, Johan Hamman criticised Kant for not having paid significant attention to the very medium that makes thinking at all possible: reason and language cannot be looked at as two different things (Lafont Reference Lafont1999). By the time Habermas used the term in the early 1970s, he was already building on the insight that the medium of language was anything but neutral with regard to thinking but, equally importantly, to action itself. The centrality of the relationships between action and speech – as expressed in J. L. Austin’s motto of ‘Doing things in saying something’ (Reference Habermas1976: 156) – is based on Habermas’s adoption of speech act theory as developed in Anglo-Saxon analytic philosophy. Habermas’s version of the linguistic turn then combines insights that come from both analytic philosophy and the ‘German’ hermeneutical tradition (Reference Habermas2003a: 51–81). But such umbrella notions as the ‘linguistic turn’ arguably hide as much as they illuminate, and in Habermas’s case there are several different claims being pursued at the same time:

1. the claim that intersubjectivity is to be preferred over consciousness as a starting point for a general anthropology;

2. the claim that communication is the best starting point for a general social theory;

3. the claim that the interiority of consciousness cannot be accessed but through language (and even then only imperfectly);

4. the claim that discursive performance works better than intentionality for symbolic meanings to be studied empirically;

5. the claim that a consensual theory of truth is to be preferred over representational or ontological theories of truth;

6. the claim that an adequate concept of human communication must include both its cognitive and its communicative use;

7. the claim that Kant’s transcendental presuppositions are to be redefined as counterfactual idealisations of language itself;

8. the claim that, because it looks at the way in which actions become coordinated, the idea of communicative action is more general than that of strategic action;

9. the claim of the relative normative primacy of the public over the private;

10. the claim that human language’s immanent orientation to understanding works also as a general normative goal in democratic decision making.

Similar to our reconstruction in other chapters, the task here is also to trace back Habermas’s ‘anthropological argument’ and reassess it in relation to his own understanding of human language and communication. For this purpose, the key texts we will look at were originally published in the 1970s, which may be seen as the transitional decade in which his ideas of communicative action and communicative rationality took shape. More precisely, we are interested in a period that began with the first delimitation of the idea of communicative action – his 1968 article Science and Technology as Ideology – and culminates in 1981 with the publication of the two volumes of Theory of Communicative Action (Habermas Reference Habermas and Habermas1971, Reference Habermas1984a, Reference Habermas1987). We will be paying close attention to how these arguments were introduced in his Christian Gauss lectures at Princeton University in 1971 (Reference Habermas2001) and also in his piece ‘What is universal pragmatics?’ of 1976 (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979). Taken together, they offer Habermas’s most systematic account of the philosophical foundations of his theory of language. But what also transpires from these texts, and this is an argument that Habermas has not explicitly pursued afterwards, is that the study of language and communicative action is to be construed around the idea of a universal ‘communicative’ or ‘interactive’ competence that does define us as members of the human species.

I

As we discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, philosophy and the social sciences in the 1970s were fundamentally influenced by cybernetics as a general scientific model with which to study all forms of communication. In Norbert Wiener’s (Reference Wiener1954) original formulation, this new science of communication turned conventional wisdom upside down: instead of highlighting our species’s uniqueness on the grounds of its linguistic prowess, human communication was a special case that needed to be studied as part of a general science of communication that applied to other forms of life as well as to increasingly ‘intelligent’ machines. Inside sociology, this insight was fully taken up by Parsons and Luhmann’s interest in communicative and symbolic processes (see Chapter 3). Habermas’s famous discussion with Luhmann in 1971 (Habermas and Luhmann Reference Habermas and Luhmann1971), as much as his adoption of the linguistic turn itself, can then be seen as his own reception of the cybernetic predicament: on the one hand, he accepts the importance of communication as a core concept for philosophy and the social sciences but, on the other hand, he rejects the idea that the specificity of human communication is derivative vis-à-vis more general, non-human, forms of communication. On the contrary, his argument is that our understanding of language and communication must proceed from the standpoint that their human features are precisely the ones to which we must pay special attention because they are a form of action. We may even see this as a particular rendition of the question of anthropocentrism that has accompanied us throughout: whether human language is to be seen as the model for other forms of communication or, conversely, whether we will only be able to fully understand human language as we radically decentre it and focus on our understanding of communication as such.Footnote 7

Habermas opens his 1971 lecture series with the proposition that meaning is to be taken as sociology’s central category (Reference Habermas2001: 3). Not altogether different from Weber’s idea that social action is always oriented towards the symbolic meanings that others may attach to it, Habermas now contends that intentional meanings are never fully dissociated from linguistic ones (Reference Habermas1984a: 102–8, 116). But it is only through language that we get empirical access to meaning: even if we still do not fully understand how this connection between language, meaning and intentions ultimately works, the fact remains that, methodologically speaking, intentions and motivations are never decoupled from the contents of linguistic utterances. The argument is not only methodological, however, because the role of the notion of meaning is itself dual: at one level, meaning refers to the semantic content of linguistic symbols; that is, it requires understanding the substantive issues that are associated with a particular symbolic content. But there is an underlying level to which more attention now needs to be devoted: meaning refers also to the explanation of the rules according to which an expression has been made and thanks to which it becomes meaningful (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979: 11–12). The delimitation of this new approach to the study of language Habermas connects it to Noam Chomsky’s idea of a generative grammar and John Austin and John Searle’s speech act theory: rather than concentrating only on ‘the content of a symbolic expression or what specific authors meant by it in specific situations’, what Chomsky in particular made clear is the need for paying systematic attention to ‘the intuitive rule consciousness that a competent speaker has of its own language’ (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979: 12, my italics).Footnote 8 Habermas then contends that, to the extent that meaning is now to play such a key methodological role in the social sciences, we have also raised the conceptual bar: we face the fundamental ‘metatheoretical decision as to whether linguistic communication is to be regarded as a constitutive feature of the object domain of the social sciences’ (Reference Habermas2001: 4, my italics).Footnote 9

Habermas then adopts what he calls an ‘essentialist’ (he will later on use ‘realist’, Reference Habermas2003a: 1–49) approach that commits to an ontological definition of its object of study. This essentialist strategy is put to work through the notion of ‘rational reconstructions’. As a methodological strategy, rational reconstructions are meant to challenge the ways in which contemporary science deals with the problem of the constitution of its object of study, on the one hand, and the relationships between expert and lay knowledge, on the other: ‘reconstructive procedures are not characteristic of sciences that develop nomological hypotheses about domains of observable events; rather, these procedures are characteristic of sciences that systematically reconstruct the intuitive knowledge of competent subjects’ (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979: 9). In a stronger formulation of this argument, Habermas then contends that for rational reconstructions to prove adequate, ‘they have to correspond precisely to the rules that are operatively effective in the object domain – that is, to the rules that actually determine the production of surface structures’ (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979: 16, my italics).Footnote 10

This is an approach that, in various forms, Habermas has continued to uphold ever since. By the mid 1980s, for instance, it remained the guiding intuition behind his reassessment of developmental psychology. Through an engagement with Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory of moral development, Habermas then sought to account for the processes that explain the rise and main features of an individual’s moral consciousness; that is, to ‘rationally reconstruct the pretheoretical knowledge of competently judging subjects’ (Reference Habermas1990a: 118). Starting with a discussion of G. H. Mead’s notion of ideal role taking, the argument is that the development of the capacity for moral judgement is to be seen as invariant, irreversible and consecutive so that a ‘hierarchy’ is being formed in which ‘structures of a higher stage dialectically sublate those of the lower one’ (Reference Habermas1990a: 127). But the key to Habermas’s argument, and here he departs from both Kohlberg and Piaget, is that we can only fully understand the way in which adults engage in moral reasoning if we are prepared to treat them both as participants in psychological experiments – thus reproducing the subject–object logic of the natural sciences – and as participants in reciprocal forms of interactions in which subjects encounter one another as euqals. The possibility of establishing the adequacy of our explanations of moral reasoning depends also on how expert statements resonate with the lay knowledge of people themselves: ‘[p]rincipled moral judgments are not possible without the first step in the reconstruction of underlying moral intuitions. Thus principled moral judgements already represent moral-theoretical judgments in nuce’ (Reference Habermas1990a: 175).

As he elaborates this further in Theory of Communicative Action, Habermas accepts that the perspectives of participants and observers are to remain different and cannot be conflated (Reference Habermas1984a: 113–17): while participants orient their actions towards specific goals, the observer must suspend all pragmatic aims other than understanding other people’s actions. But this cannot be turned into the arguments that observers have a superior understanding of lay actions. Habermas contends that the kind of ‘virtual participation’ that define social scientists in their expert roles does not fully liberate us from the need to understand reasons as reasons; rather the opposite, ‘on this point, which is decisive for the objectivity of understanding, the same kind of interpretive accomplishment is required of both the social-scientific observer and the layman’ (Reference Habermas1984a: 116). In other words, for the social scientific observer to genuinely understand an action or linguistic utterance, she cannot but have recourse to the same lifeworld traditions as participants themselves. Thus seen, the scientific observer:

must already belong in a certain way to the lifeworld whose elements he wishes to describe. In order to describe them, he must understand them; in order to understand them, he must be able in principle to participate in their production; and this participation presupposes that one belongs … this circumstance prohibits the interpreter from separating questions of meaning and questions of validity in such a way as to secure for the understanding of meaning a purely descriptive character.

The key point here is that the very idea of validity requires observers to be able to grasp the reasons that are being offered in support or rejection of a particular situation. But this perspective is only methodologically available in their role as participants: ‘reasons are of such a nature that they cannot be described in the attitude of a third person, that is, without reactions of affirmation or negation or abstention. The interpreter would have understood what a “reason” is if he did not reconstruct it with its claim to provide grounds; that is, if he did not give it a rational interpretation in Max Weber’s sense’ (Reference Habermas1984a: 115–16).

It is thus worthy of mention that Habermas concedes that his project is based on a ‘naturalistic ring’ that highlights those general properties or abilities that define the species as a whole; what we are genuinely talking about here is the ‘ontogenesis’ of a very unique human ‘capacity for speech and action’ (Reference Habermas1990a: 130).Footnote 11 But arguably more salient is one normative implication that becomes immediately apparent: there’s an egalitarianism of perspectives that necessarily underpins the study of human linguistic interactions: as competent speakers of particular linguistic communities, scientists and philosophers do not have a position of privilege vis-à-vis lay actors. An argument to which we will return below, we can see that symmetry and reciprocity are central to Habermas’s normative preference for an ideal speech situation: ‘the counterfactual conditions of the ideal speech situation can also be conceived of as necessary conditions of an emancipated form of life’ (Reference Habermas2001: 99). On the one hand, this egalitarianism accounts for the fact that human communication has an immanent connection not only to an idea of truth but also to notions of freedom, autonomy and responsibility – all of which refer to the accountability of one’s actions (Reference Habermas2001: 99–101). On the other hand, this egalitarianism has also wider implications vis-à-vis the emancipatory tasks of critical theory in general, and democratic decision making in particular: ‘[t]he formal anticipation of idealized conversation (perhaps as a form of life to be realized in the future?) guarantees the “ultimate” underlying counterfactual mutual agreement, which does not first have to be created, but which must connect potential speaker-hearers a priori’ (Reference Habermas2001: 102).Footnote 12 The intrinsic normative dimension of social life depends on the fact that our linguistic interactions are oriented towards understanding and that the idea of ‘reaching a mutual understanding is a normative concept’. Habermas then concludes that ‘[o]n this inevitable fiction rests the humanity of social intercourse among people who are still human, that is, who have not yet become completely alienated from themselves in their self-objectifications’ (Reference Habermas2001: 102, my italics).

This notion of idealisation plays a major role in Habermas’s argument: there is not only an ideal speech situation but also an ideal speaker-listener-actor whose own ‘ideal rule-competence’ becomes the anthropological feature that makes human communication possible. This again builds on Chomsky’s idea of an ‘innate linguistic capacity’ that is available to ‘all normally socialized members of a speech community’: to the extent that they ‘have learned to speak at all’, they must have a ‘complete mastery of the system of abstract rules’ (Reference Habermas2001: 71). While the actual performance of this competence can be more or less accomplished, as a general competence it is universally available and ‘cannot be distributed differentially’ (Reference Habermas2001: 71): differently put, this communicative competence is general and universal but its performance is empirically differentiated and allows for degrees of skilfulness. Habermas speaks of the need to uphold a weak transcendentalism which, rather than thinking about the a priori conditions of all possible experiences (as in Kant’s traditional version of this argument), takes a fallibilist approach whereby its claim to generality is sustained equally seriously though always provisionally: ‘[a]s long as the assertion of its necessity and universality has not been refuted, we term transcendental the conceptual structure recurring in all coherent experiences … the claim that that structure can be demonstrated a priori is dropped’ (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979: 21–2). Habermas then transforms ‘Kant’s “ideas” of pure reason into “idealising” presuppositions of communicative action’, whereby the idea of reason is transformed from ‘the highest court of appeal’ into ‘rational discourse as the unavoidable forum of possible justification’ (Reference Habermas2003a: 85, 87). This de-transcendentalisation aims to leave the problems of Kant’s philosophy behind, and Habermas claims that this is central to the paradigmatic shift that the linguistic turn effectuates: ‘[t]he rigid “ideal” that was elevated to an otherworldly realm is set aflow in this-worldly operations; it is transposed from a transcendent state into a process of “immanent transcendence.”’ (Reference Habermas2003a: 92–3).Footnote 13

A line of critique that we first encountered in the Introduction when we discussed Ralf Dahrendorf’s idea of homo sociologicus, Habermas also contends that role theories in sociology bring some of these issues into view: yet as they pay excessive attention to passivity and conformity, role theories are ultimately underpinned by an oversocialised conception of the human in which personality structures are deemed to merely reflect institutionalised values. While he does not use the language of human nature, Habermas’s claim is effectively that sociological theories of role have an insufficient understanding of the underlying human attributes that make role acquisition at all possible. These theories concentrate only on their application to specific contents and cultural traditions and do not theorise the very competence that allows for roles to be developed: as they tend to work as a middle-range approach, they lack philosophical depth (Reference Habermas1984a: 76–82). It is however the idea of the general capabilities of the human agent that is at stake here, so the challenge is to make clear the possible correspondence between psychological or personality traits and social structures: ‘I am convinced that the ontogenesis of speaker and world perspectives that leads to a decentered understanding of the world can be explained only in connection with the development of the corresponding structures of interaction’ (Reference Habermas1990a: 138, underlining mine).Footnote 14

The full implications of these arguments will be unpacked below, but we can already highlight three of them: First, because the conditions of possible linguistic communication are not derived a priori (as in Kant), they themselves must be susceptible of empirical study. This justifies the need for the rational reconstruction of those general attributes that make human communication possible. Second, because human experiences do not refer only to events in the natural world that can be reconstructed vis-à-vis causal laws, we need also to conceptualise how interactive and communicative events are apprehended through interpretations.Footnote 15 Third, because we are speaking of human communication, we must be able to reconstruct the general set of anthropological capabilities that make communication possible both in terms of properties that develop within the lifecycle of any individual member of the species (ontogenesis) and as properties that mark the evolution of the species as a whole (phylogenesis).

II

Human language and interaction are of course ‘external’ events in the world, but we only have access to them through the ‘internal’ medium that is linguistic communication. For us to be able to account for this peculiarly internal and external condition of language, we first have to be able to grasp the human competences that make it possible. This, Habermas contends, is to be achieved by unpacking the underlying system of rules – historical and invariable – within which these processes take place (Reference Habermas2001: 11). Because of this duality of external and internal tasks, moreover, the meaning of linguistic utterances needs ultimately to refer back to the particular subject who had offered the emission (even if she may not be aware of the rules that made it possible). It is in this context that Habermas will openly argue that a monological model – that is, a conception of language that starts from an isolated individual – is fundamentally inadequate because the idea of symbolic meanings points to something that is already trans- or inter-individual. In terms of the philosophical tradition, Habermas rejects those approaches that, most famously in Kant, Husserl and Simmel, take the isolated individual as their initial building block and then look at meanings as a reflection of the internal states of an autonomous consciousness. Equally forcefully, he rejects the idea of human communication that is offered in so-called ‘externalist’ models, as espoused by system theory and structuralism: while they do not make meaning dependent on allegedly autonomous states of consciousness, these approaches fail because they cannot be traced back to the subjects’ own self-understanding: neither individualists nor collectivists are able to give ‘an accurate account of how intersubjectively binding meaning structures are generated’ (Reference Habermas2001: 16–17).

One main idea for this chapter has now revealed itself: the version of the linguistic turn that Habermas has adopted is one that, contrary to its more radical versions, cannot do away with a general anthropology. It requires him instead to redefine the terms within which it is to remain feasible. The challenge then becomes that of reconstructing the intrinsic capabilities that underpin the use of all human languages: ‘[i]n principle, anyone who masters a natural language can, by virtue of communicative competence, understand an infinite number of expressions, if they are at all meaningful, and make them intelligible to others’ (Reference Habermas2001: 7, my italics). We need to be able to construe a general procedure that can explain how are these skills possible at all; in other words, ‘a theory of ordinary-language communication that did not merely guide and discipline the natural faculty of communicative competence, as hermeneutics does, but could also explain it’ (Reference Habermas2001: 8, my italics). It is this idea of a communicative competence that we now have to reconstruct in detail.

An argument that we have encountered before, the first property of the idea of a communicative competence is that its very conception ‘must be derivable from the self-understanding of the very subjects who produce these structures’; we need to reconstruct ‘the implicit know-how of competent subjects capable of judgement. What is to be explicated by these reconstructions are the operationally effective rules themselves’ (Reference Habermas2001: 10, my italics). A human subject is able to acquire and then perform roles efficiently because she is a person who is capable of knowledge, language and action. This, it seems to me, is key to Habermas’s project of studying the human: the reconstruction of the possibility of congruence in the differentiated developments between cognitive, linguistic and interactive skills. These competences are of course interconnected but they develop independently from one another because we engage differently with external nature, language and society as the main objectual domains which, as they define human life, are to be seen as quasi-transcendental (Reference Habermas and Habermas1984b: 188–92).

Habermas published in 1974 a piece where he offers a relatively short though systematic attempt to further delineate this quest. Possibly in order to emphasise the pragmatic side of his argument, Habermas speaks there of an interactive rather than of a communicative competence: at stake here are not only our linguistic skills but our more general abilities to interact competently with each other and the world. Although it is a piece that Habermas partly disowned afterwards (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979: 210), what matters to us here is how it explicitly defines the terms of the enquiry as the need for a general anthropology that looks at those competences that constitute us as members of the species: ‘[t]he use of the expression “interactive competence” points to the fundamental presupposition that we can investigate a subject’s capacities for social action from the point of view of a universal competence that is independent from any particular culture and in a way that is similar to their normal capacities for speech and knowledge’ (Reference Habermas and Habermas1984b: 187).Footnote 16

Conventionally, discussions on Habermas’s universal pragmatics have centred on two sets of issues (McCarthy Reference McCarthy1985: 272–91). First, there is the question of the methodological status of rational reconstructions as the procedure that is to give us access to these general capacities. Here, one line of criticisms mirrors those that have been made against Chomsky’s notion of a general competence and also against Piaget’s idea of necessary evolutionary stages; namely, whether the idea of such a general competence can be credited at all. Secondly, Habermas builds on the distinction between know how and know that; that is, the difference between being successful in applying a rule and the ability to logically reconstruct and explain the rule itself (Reference Habermas2001: 67–8). Usual examples here include the relations with those technological devices that we are able to manipulate efficiently regardless of how little we know how or why they behave in the way that they do. When it comes to language and interactions – and their basic units of analysis, sentences and utterances – Habermas’s argument does seem straightforward: our ability to speak our mother tongue as much as the ability to efficiently interact in everyday social contexts are indeed independent from our ability to reconstruct the underlying grammar and sociocultural traditions that make these interventions appropriate.Footnote 17 Genuine skilfulness requires a level of improvisation and ‘feel for the game’ that resists formalisation: F1 car mechanics and designers are not the fastest drivers of the cars they build; the mastery of the sociology of a particular set of social conventions does not secure that one’s actions will be received as expected.

But here I would like to concentrate on a different dimension of Habermas’s idea of a communicative or interactive competence. The notion of a universal pragmatics is itself ambivalently defined as being concerned with two, rather different, objects of study: universal pragmatics is meant to look into: (a) speech acts as the minimal units of language as they take place in contexts of interaction; and (b) a communicative or interactive competence as the general ability to generate and then follow the rules that account for successful linguistic interactions. My argument is that there is a constant tension in Habermas’s argument so that he focuses, rather inconsistently, on both: the delineation of that general human capacity that is the communicative competence and the linguistic events in the world that represent the successful manifestation of this capacity. In one of the first definitions of universal pragmatics, in 1971, Habermas explicitly mentions both dimensions:

A theory of communicative competence must explain what speakers or hearers accomplish by means of pragmatic universals when they use sentences (or non verbal expressions) in utterances … Universal pragmatics aims at the reconstruction of the rule system that a competent speaker must know if she is to be able to fulfil this postulate of the simultaneity of communication and metacommunication. I should like to reserve the term communicative competence for this qualification.

In his 1976 text on universal pragmatics, the general orientation of his project has not changed dramatically but the emphasis is now on the ‘intuitive evaluations’ that will allow for the reconstruction of a ‘pretheoretical knowledge of a general sort’ (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979: 14). Habermas focuses on the genuinely universal capabilities that define us as members of the species, but as soon as he has made this the task of a universal pragmatics he runs again into the same duality of tasks: ‘[w]hen the pretheoretical knowledge to be reconstructed expresses a universal capability, a general cognitive, linguistic, or interactive competence (or subcompetence), then what begins as an explication of meaning aims at the reconstruction of species competences’ (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979: 14, my italics). The object of study is defined as the ability of human speakers to connect speech and reality, but we can also see that there is a whole range of empirical tasks that, as pragmatic accomplishments, cannot be reduced to the reconstruction of a general capability; instead, they can only be studied as empirical events in the outside world because they are successful with regard to social or linguistic expectations. Habermas thus speaks of the need to ‘reconstruct the ability of adult speakers to embed sentences in relations to reality in such a way that they can take on the general pragmatic functions of representation, expression and establishing legitimate interpersonal relations’ (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979: 32–3, my italics). Here, he is talking about practical accomplishments such as artistic expressions, the paraphrasing of utterances that are seen as an individual’s social skills, and indeed the ability to contextually translate from and into different languages.

To be sure, some of these ambivalences can be explained away on the grounds that these are all transitional texts that do not represent definitive formulations. But, as Habermas himself contends as he discusses other authors, early difficulties in theory construction may offer also a window into more substantive challenges. In this case, Habermas seems to have been at least partly aware of this difficulty when he warns against the risk of the notion of a communicative competence becoming merely a ‘hybrid concept’ (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979: 26–7); that is, a category that fails to have substantive purchase. But this reinforces rather than overcomes the tension of crediting universal pragmatics with the task of reconstructing both: (1) the successful social performance of, (2) a particular anthropological competence.Footnote 19 This does make Habermas’s argument look like a case of central conflation (Archer Reference Archer1995): rather than the interplay between two clearly distinct ontological levels – a general anthropology that is autonomous vis-à-vis social settings – Habermas seems to be eliding the human (i.e. the competence) and the social (i.e. the success of the utterances themselves).Footnote 20

But it has been my argument so far that the most consistent version of Habermas’s argument depends on holding on to the autonomous properties of humans as the beings who are defined by an autonomous capability whose success is however ultimately social. By the time of the publication of Theory of Communicative Action Habermas seems to have acknowledged this difficulty and narrowed down his argument in two significant ways. First, he now argues that recent developments in ethnomethodology and philosophical hermeneutics do show that we have to presuppose the idea of a universal interactive competence (for the case of ethnomethodology) and of an equally universal interpretative competence (for the case of hermeneutics, Reference Habermas1984a: 130).Footnote 21 This demonstrates, Habermas contends, that even competing scientific programmes in the social sciences have to presuppose a similar universal human competence of this kind. Yet Habermas is also forced to concede that he is ‘no longer confident that a rigorous transcendental-pragmatic programme’, as the one offered by universal pragmatics, can be successfully ‘carried out’ (Reference Habermas1984a: 137). In other words, the strong programme for the rational reconstruction of communicative competence remains elusive vis-à-vis the cognitive standards of modern science. Habermas even accepts that the very decision to structure Theory of Communicative Action as a theory of the rationalisation of modern society is based on the fact that such a reconstruction is ‘less demanding’ than the original project of a universal pragmatics (Reference Habermas1984a: 139). The second argument refers to Habermas’s early intuition with regard to the role of a theory of communicative competence for the purposes of the renewal of critical theory. In the original formulation, this revitalisation was in fact central for the justification of universal pragmatics:

for every possible communication, the anticipation of the ideal speech situation has the significance of a constitutive illusion that is at the same time the prefiguration of a form of life … From this point of view the fundamental norms of possible speech that are built into universal pragmatics contain a practical hypothesis. This hypothesis, which must first be developed and justified in a theory of communicative competence, is the point of departure for a critical theory of society.

As Habermas engages again with this claim in Theory of Communicative Action, doubts as to whether universal pragmatics can be put to work as an empirical research programme do not make him question its overall relevance within his project:

Linking up with formal semantics, speech-act theory, and other approaches to the pragmatics of language, this is an attempt at rationally reconstructing universal rules and necessary presuppositions of speech actions oriented to reaching an understanding. Such a program aims at hypothetical reconstructions of that pretheoretical knowledge that competent speakers bring to bear when they employ sentences in actions oriented to reaching understanding. This program holds out no prospect of an equivalent for a transcendental deduction of the communicative universals described. The hypothetical reconstructions must, however, be capable of being checked against speakers’ intuitions, scattered across as broad a sociocultural spectrum as possible. While the universalistic claim of formal pragmatics cannot be conclusively redeemed (in the sense of transcendental philosophy) by way of rationally reconstructing natural intuitions, it can be rendered plausible in this way.

We have to remember that this definition is introduced just before he begins the long march in the study of modern rationalisation processes from traditional societies to contemporary capitalist legitimisation crises. Speakers continue to be depicted as competent but the research programme itself is to be dedicated exclusively to the reconstruction of events in the world that must also be made compatible with lay actors’ self-descriptions. In other words, we are still confronted with the idea that only humans (as opposed to animals) and symbolic expressions (as opposed to natural events) can be depicted as rational in a strong sense. And the reference to rule-following has now been explicitly transferred into an enquiry of how they can be reconstructed as linguistic expressions in the world. But if Habermas has watered down the idea of a general competence for the more moderate enquiry into the competent deployment of various expressions and utterances, it is then difficult to see how exactly is this interpreter different from the shallower role-bearer of conventional functionalist sociology.

III

Habermas’s idea of the lifeworld is built on a tensional relationship with Husserl. At the same time as he criticises Husserl’s reliance on consciousness as an obstacle for the development of a fully-fledged linguistic turn, Habermas turns to Husserl in order to reclaim the idea that, because the natural sciences are a cultural construction, they are themselves to be studied within particular lifeworlds. This does not necessarily undermine the truth-value of the natural sciences, but we need to be able to include them within a wider enquiry into the workings of the lifeworld itself. A rejection of a positivistic self-understanding of science, while remaining committed to their claim to validity, now requires a new theory of the constitution of the lifeworld itself; a general theory of knowledge is always more complex and general than the theory of science that arises within it. Indeed, one of Habermas’s (Reference Habermas1972) main argument in Knowledge and Human Interest was precisely that a theory of science depends on a theory of knowledge, which in turn depends on a general theory of society.

The lifeworld is then defined as a complex sociocultural web that encompasses all dimensions of everyday life. There is no single or unifying experience inside the lifeworld and this variety of modes of experiences is yet another expression of the fact that an externalist attitude that focuses, for instance, on the laws of causality that we use to describe events in the natural world, has no primacy in our everyday life. If anything, Habermas contends, it is the experience of linguistic socialisation that is truly universal: we encounter ‘others’ as socialised individuals with whom we establish interpersonal rather than instrumental relations. An argument that is also apparent in Hans Blumenberg’s (Reference Blumenberg2011) reconstruction of Husserl’s phenomenology, Habermas contends that Husserl accepts the centrality of intersubjectivity in a way that Kant did not, but that the concept of intersubjectivity that he offers remains problematic. We need to go beyond Husserl if we are to explain how people experience the presence of others as persons; that is, the connections we make between the experience of a human body as a physical event in the world and the interpersonal relations we establish with fellow human beings. We owe to our communicative competence the possibility to decide when and how to exchange positions in social interaction: ego and alter see each other as identical (as humans) and distinct (in their bodily constitution, personality and sociocultural standpoints). If, on the minus side, Husserl was unable to articulate a consistent concept of intersubjectivity, on the plus side his idea of the lifeworld points Habermas in the direction of the immanent relationship between truth and society:

Every society that we conceive of as a meaningfully structured system has an immanent relation to truth. For the reality of meaning structures is based on the peculiar facticity of claims to validity: In general, these claims are naively accepted – that is, they are presumed to be fulfilled. But validity claims can, of course, be called into question. They raise a claim to legitimacy, and this legitimacy can be problematized … We can speak of “truth” here only in the broad sense of the legitimacy of a claim that can be fulfilled or disappointed.

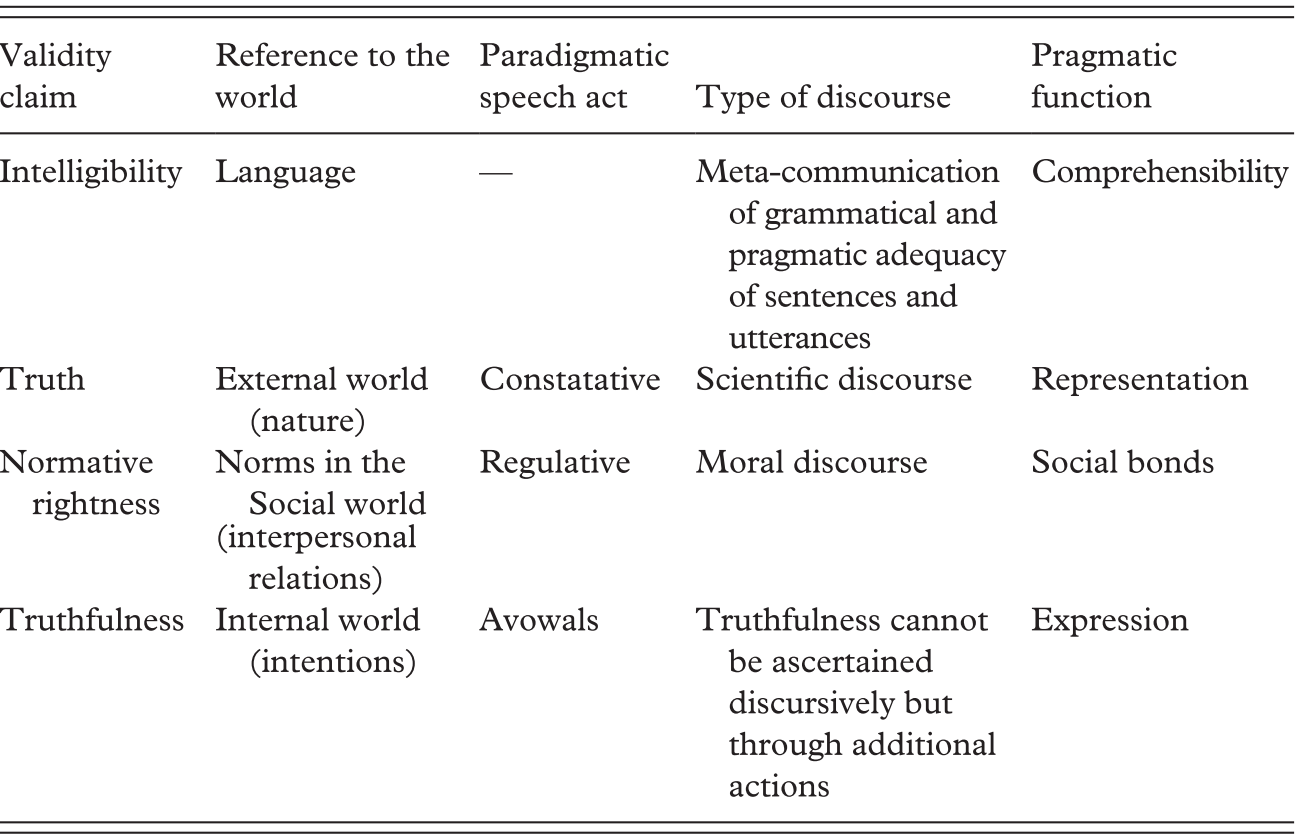

This is a fundamental proposition for Habermas: when we make a statement, we assert it as true. Being linguistically articulated, the claims to validity of our utterances depend on our intentions and on the features of the sociocultural lifeworld that we inhabit. Thus conceived, truth can no longer refer only to objective states in the world (as in the natural sciences) but must also include one’s own subjectivity, as well as the justification of social norms themselves. In redefining a theory of truth in this way, Habermas no longer accepts those theories that conceive truth in terms of adequacy with the external world; he focuses instead on the rules of discourse itself. Habermas’s well-known notion of validity claims that are redeemed not through intuition, intention or even interaction, but discursively, belongs here: the ‘legitimacy’ of validity claims ‘can be established only in discourse. What is anticipated in these positings … is not the possibility of the intuitive fulfilment of an intention, but justifiability: that is the possibility of a consensus, obtained without force, about the legitimacy of the claim in question’ (Reference Habermas2001: 34–5, my italics). There is no need here to go into the details of Habermas’s argument about validity claims; for our purposes, it is enough that we summarise their main contours (see Table 5.1).

Table 5.1. Habermas’s theory of truth and main validity claims1

1 Habermas’s presentation of this argument can be found in (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979: 28; Reference Habermas1984a: 23–42; Reference Habermas1990a: 136–7, Reference Habermas2001: 63–4, 90–1). The two main modifications to the theory are: (1) intelligibility is not strictly speaking a validity claim but a precondition of communication itself and (2) truthfulness cannot be fully actualised in rational discourse but only in social contexts: ‘[c]laims to sincerity can be redeemed only through social life itself’ (Reference Habermas2001: 93).

Habermas’s distinction between communicative action, as the type of social action that is oriented towards reaching an understanding, and discourse, as the argumentative practice that focuses on the linguistic redemption of validity claims that have become problematic, is the core of his consensual theory of truth (Reference Habermas2001: 99–100). In its original version, the argument is that, when validity claims are redeemed in rational argumentations, they refer to the adequacy of other arguments and the conditions of validity of arguments, but they do not refer directly to external evidence. In turn, this means that, for the purposes of a theory of society, we need a conception of language that not only has cognitive use (i.e. a use of language that refers to things in the world) but also has communicative use (i.e. that dimension of human communication that focuses explicitly on intersubjective relations). This is the case, moreover, because agreement over the semantic qualities of an utterance (i.e. cognitive use of language) is itself only available intersubjectively (i.e. communicative use of language):

Communicative language use presupposes cognitive use, whereby we acquire propositional contents, just as, inversely, cognitive use presupposes communicative use, since assertions can only be made by means of constatative speech acts. Although a communicative theory of society is immediately concerned with the sedimentations and products of communicative language use, it must also do justice to the double, cognitive-communicative structure of speech. Therefore, in developing a theory of speech acts, I shall at least refer to the constitutive problems that arise in connection with cognitive language use.

It is through this dual use of language that Habermas breaks also with too narrow a model of linguistic games. The idea of language games is appealing because it accounts for the fact that rules are obligatory due to their intersubjective validity. At the same time, language games are not mere games because language constitutes us as the beings who we actually are (Reference Habermas2001: 57). In society, following a rule implies the possibility of meta-communication over the rule itself: there has to be a human being who is able to say ‘no’ (Reference Habermas1990a: 137, White and Farr Reference White and Farr2012). But while games stop when we meta-communicate over their rules, the grammatical rules of natural languages cannot be changed or renegotiated to a similar extent: the kind of reflexivity that is involved in linguistic communication is itself linguistically articulated. In social interaction, communication always presupposes the possibility of meta-communication, but in some formulations Habermas’s argument is even more demanding; he claims that the two are in fact simultaneous: ‘communication through meaning is possibly only on condition of simultaneous metacommunication. Communication by means of shared meanings requires reaching an understanding about something and simultaneously reaching an understanding about the intersubjective validity of what is being communicated’ (Reference Habermas2001: 60, my italics).

If not outright problematic, this clause on simultaneity requires at least some further clarification. There is of course one sense in which Habermas is right, as human language has reflexivity and meta-communication built into it: ‘[b]ecause of the reflexive character of natural languages, speaking about what has been spoken, direct or indirect mention of speech components, belongs to the normal process of reaching an understanding’ (Reference Habermas and Habermas1979: 18, my italics). Indeed, it is this reflexive character of language that is central to Habermas’s translation of Kant’s categorical imperative of morality into a discursive principle. The reflexivity of the discourse principle is as central as its inclusivity and universality: democratic discourse is one of the conditions that secures the rationality of a decision.Footnote 25 At this level, the condition of simultaneity does not seem particularly problematic: if linguistic utterances are a form of action, then speech acts refer both to something in the world and to an interpersonal relation. But the argument does not really work in the first use of simultaneous above: meta-communication is always presupposed in communication, and is surely its implicit background, but this is precisely why it cannot be simultaneous with it. Habermas himself seems to recognise this much when he distinguishses between communicative action as a form of interaction that seeks to reach a rational consensus and discourse as the type of linguistic performance in which speakers have to justify validity claims that have become problematic: discourse is a form of meta-communication that is only possible when communicative action is suspended. Crucially, Habermas contends that there is no such thing as a meta-discourse (Reference Habermas2001: 179).

There is still one further question that is worth mentioning in relation to Habermas’s linguistic theory of truth.Footnote 26 After twenty years in which he systematically defended the idea of a strictly consensual theory of truth that was based on the possibility of redeeming claims to validity, Habermas now contends that an adequate theory of truth cannot rely only on discursive performance. Instead, truth claims must ultimately make a reference to things in the world: ‘no matter how carefully a consensus about a proposition is established and no matter how well the proposition is justified, it may nevertheless turn out to be false in light of new evidence. It is precisely this difference between truth and ideal warranted assertability that is blurred with respect to moral claims to validity’ (Reference Habermas2003a: 257, my italics). Claims to truth become more neatly differentiated from claims to normative rightness because the latter do remain wholly within the linguistic parameters of justifiability: ‘assertability is what we mean by moral validity … A norm’s ideal warranted assertability … does not refer beyond the boundaries of discourse to something that “exist” independently of having been determined to be worthy of recognition. The justification-immanence of “rightness” is based on a semantic agreement’ (Reference Habermas2003a: 258). Habermas then speaks of realism in cognitive theory – truth validity claims do ultimately refer to things in the (natural) world that exist independently of our ability to recognise them – and constructivism in moral theory – claims to normative rightness do not possess such an external locus and are wholly the result of human interaction itself (Reference Habermas2003a: 266, Lafont Reference Lafont2004).Footnote 27

For our purposes, the main purchase of this argument is that it further checks the potentially relativistic implication of an idea of truth that can wholly do without a reference to the outside world and is reduced to whatever statements we are able to agree on. Also, it reinforces Habermas’s long-standing claim of the radical differentiation between the external standpoint of the observer that makes statements about the natural world and the internal or realisative position of participants in interactive processes: while the former allows for hierarchical forms of communication, the latter necessarily involves symmetry and reciprocity. And this is in fact consistent with a main difference between Habermas’s position and those of Kohlberg and Piaget: while the latter two contend that the evolution of moral and cognitive structures follow the same pattern, Habermas contends that this is not the case and they need to be differentiated (Reference Habermas2003a: 243–9).

But I also see two difficulties in this reworking of Habermas’s theory of truth: by reasserting the need to connect consensual discourse and ‘external reality’, truth is now implicitly equated with technical efficiency; that is, events in the world that we can claim to have actually taken place even if we do not know how or why this is the case. Conversely, if normative rightness now needs to make no reference whatever to the world outside discourse – then the physical, emotional and indeed moral integrity of human beings runs the risk of being dramatically undermined as a mere sociocultural construct. Yet this is not how Habermas articulates his position explicitly, for instance, in terms of the inclusivity of his principle of discourse ethics:

the unconditional nature of moral validity claims can be accounted for in terms of the universality of a normative domain that is to be brought about: Only those judgements and norms are valid that could be accepted for good reasons by everyone affected from the inclusive perspective of equally taking into consideration the evident claims of all persons.

A stronger theory of truth in relation to the external world cannot simply be bought at the expense of a weakened theory of normative rightness that may fall for the performative contradiction of favouring anything that may be achieved through a rational argument. And this is indeed Habermas’s position as he spells out his support for universalistic ideas of human rights and dignity (Reference Habermas2003a, Reference Habermas2010). It is our constitution as human beings, as beings who are simultaneously a physical event in the world and a normative source of mutual recognition, that creates a real problem. In the language of philosophical anthropology, to treat human beings as persons requires also a clear commitment to the external locus that makes possible our continuous organic existence.

This question reappears as part of a standard criticism that is against Habermas’s argument: the aporias of a universalistic morality in the context of pluralist societies (Dux Reference Dux, Honneth and Joas1991, Taylor Reference Taylor, Honneth and Joas1991a. See also Chapter 6). The core of this critique is well known: given that universalistic positions have originated from and are articulated within a particular sociocultural traditions, their purported universality is little else than the hypostatisation of a particular. Habermas’s replies to this critique have taken several forms, but the one that matters the most once again resorts to his idea of a communicative competence: ‘[t]he question of the context-specific application of universal norms should not be confused with question of their justification. Since moral norms do not contain their own rules of application, acting on the basis of moral insight requires the additional competence of hermeneutic prudence, or in Kantian terminology, reflective judgment’ (Reference Habermas1990a: 179–80, my italics).Footnote 28 The point that this critique misses, and here Habermas’s position is to be upheld, is that the general orientation towards neutrality, reciprocity and inclusivity that we demand of normatively legitimate social institutions is built into the very nature of human communication itself. Differently put, it is one thing to contend that Habermas’s position is not wholly unproblematic with regard to the justification of its own distinction between the universality of morality and the particularity of ethical life, and something different to reject the principle of universality that makes possible our ideas of autonomy, solidarity and justice.

There is, however, one key proposition that has arguably remained the same from the very start of Habermas’s project: there has to be some correspondence between truth, freedom and justice, on the one hand, and the centrality of the theory of a communicative or interactive competence, on the other hand. This convergence is based precisely on the fact that it specifies the anthropological features that offer the independent justification for the social realisation of these universal values: ‘justice can be gleaned only from the idealized form of reciprocity that underlies discourse’ (Reference Habermas1990a: 165). This argument on autonomy and responsibility figures centrally at the beginning of Theory of Communicative Action (Reference Habermas1984a: 14–16), and the implications that ultimately matter to us are twofold: first, Habermas’s implicit idea of human nature remains that of a ‘morally neutral agent’ (Papastephanou Reference Papastephanou1997: 59). While a certain ‘idealism’ may be found in the centrality Habermas gives to linguistic utterances, we should not lose sight of the fact that these are precisely utterances in the pragmatic sense that they can only be reconstructed vis-à-vis the wider contexts within which they are made. Not only that, Habermas’s differentiated concept of truth, problematic as it ultimately is, remains committed to a differentiated account of the relationships humans establish with the external environments of the natural and sociocultural worlds, on the one hand, and their internal psychological states, on the other. Second, ideas of critique and justification remain central to Habermas’s project and cannot be seen only as a property of linguistic communication. They refer also to the most fundamental anthropological capacities that we possess as human beings.Footnote 29 In Habermas’s version at least, the linguistic turn that made it possible to uncover the fundamentally linguistic nature of critique and justification does not change the fact they are exercised by competent subjects who have the ability to do so: justification, as the ability to give reasons becomes the counterpoint of critique, the ability to demand them.

Habermas’s adoption of the linguistic turn in the early 1970s left a lasting legacy in his intellectual development. Not without its problems, the centrality of language in terms of its dual anthropological and social dimensions is a major contribution to my project of a philosophical sociology. As he thinks through the main dimensions of human language, Habermas looks for the articulation between science and philosophy, ontogenesis and phylogenesis, the cognitive and the moral, the public and the private, the internal perspective of actors and the external perspective of observers, the democratic and the technocratic, and even between different types of validity claims and rationalisation processes. Habermas’s idea of a communicative or interactive competence works as the anthropological core of a universalistic principle of humanity with the help of which we bring together the different knowledge-claims of science and philosophy as necessary components of an adequate understanding of the normative dimensions of social life.